Thank You Fiends: Big Star's "Third/Sister Lovers"

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Star Shines at Shell

May 24, 2014 Star Shines at Shell PHOTO BY YOSHI JAMES Homage to cult band’s “Third” kicks off Levitt series By Bob Mehr The Levitt Shell’s 2014 summer season opened Friday night, with a teeming crowd of roughly 4,000 who camped out under clear skies to hear the music of Memphis’ greatest cult band Big Star, in a show dedicated to its dark masterpiece, Third. Performed by an all-star troupe of local and national musicians, it was yet another reminder of how the group, critically acclaimed but commercially doomed during their initial run in the early 1970s, has developed into one of the unlikeliest success stories in rock and roll. The Third album — alternately known as Sister Lovers — was originally recorded at Midtown’s Ardent Studios in the mid-’70s, but vexed the music industry at the time, and was given a belated, minor indie-label release at the end of the decade. However, the music and myth of Third would grow exponentially in the decades to come. When it was finally issued on CD in the early ’90s, the record was hailed by Rolling Stone as an “untidy masterpiece ... beautiful and disturbing, pristine and unkempt — and vehemently original.” 1 North Carolina musician Chris Stamey had long been enamored of the record and the idea of recreating the Third album (along with full string arrangements) live on stage. He was close to realizing a version of the show with a reunited, latter- day Big Star lineup, when the band’s camp suffered a series of losses: first, with the passing of Third producer Jim Dickinson in 2009, and then the PHOTO BY YALONDA M. -

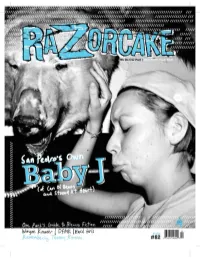

Razorcake Issue #82 As A

RIP THIS PAGE OUT WHO WE ARE... Razorcake exists because of you. Whether you contributed If you wish to donate through the mail, any content that was printed in this issue, placed an ad, or are a reader: without your involvement, this magazine would not exist. We are a please rip this page out and send it to: community that defi es geographical boundaries or easy answers. Much Razorcake/Gorsky Press, Inc. of what you will fi nd here is open to interpretation, and that’s how we PO Box 42129 like it. Los Angeles, CA 90042 In mainstream culture the bottom line is profi t. In DIY punk the NAME: bottom line is a personal decision. We operate in an economy of favors amongst ethical, life-long enthusiasts. And we’re fucking serious about it. Profi tless and proud. ADDRESS: Th ere’s nothing more laughable than the general public’s perception of punk. Endlessly misrepresented and misunderstood. Exploited and patronized. Let the squares worry about “fi tting in.” We know who we are. Within these pages you’ll fi nd unwavering beliefs rooted in a EMAIL: culture that values growth and exploration over tired predictability. Th ere is a rumbling dissonance reverberating within the inner DONATION walls of our collective skull. Th ank you for contributing to it. AMOUNT: Razorcake/Gorsky Press, Inc., a California not-for-profit corporation, is registered as a charitable organization with the State of California’s COMPUTER STUFF: Secretary of State, and has been granted official tax exempt status (section 501(c)(3) of the Internal Revenue Code) from the United razorcake.org/donate States IRS. -

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs No. Interpret Title Year of release 1. Bob Dylan Like a Rolling Stone 1961 2. The Rolling Stones Satisfaction 1965 3. John Lennon Imagine 1971 4. Marvin Gaye What’s Going on 1971 5. Aretha Franklin Respect 1967 6. The Beach Boys Good Vibrations 1966 7. Chuck Berry Johnny B. Goode 1958 8. The Beatles Hey Jude 1968 9. Nirvana Smells Like Teen Spirit 1991 10. Ray Charles What'd I Say (part 1&2) 1959 11. The Who My Generation 1965 12. Sam Cooke A Change is Gonna Come 1964 13. The Beatles Yesterday 1965 14. Bob Dylan Blowin' in the Wind 1963 15. The Clash London Calling 1980 16. The Beatles I Want zo Hold Your Hand 1963 17. Jimmy Hendrix Purple Haze 1967 18. Chuck Berry Maybellene 1955 19. Elvis Presley Hound Dog 1956 20. The Beatles Let It Be 1970 21. Bruce Springsteen Born to Run 1975 22. The Ronettes Be My Baby 1963 23. The Beatles In my Life 1965 24. The Impressions People Get Ready 1965 25. The Beach Boys God Only Knows 1966 26. The Beatles A day in a life 1967 27. Derek and the Dominos Layla 1970 28. Otis Redding Sitting on the Dock of the Bay 1968 29. The Beatles Help 1965 30. Johnny Cash I Walk the Line 1956 31. Led Zeppelin Stairway to Heaven 1971 32. The Rolling Stones Sympathy for the Devil 1968 33. Tina Turner River Deep - Mountain High 1966 34. The Righteous Brothers You've Lost that Lovin' Feelin' 1964 35. -

Debuten Til Hardrocker'ne Fra Down Under. 6.Albumet I Rekken Av

ARTIST / BANDNAVN ALBUM TITTEL UTG.ÅR LABEL/ KATAL.NR. LAND LP KOMMENTAR A New wave/synthpop fra Sheffield band, med Martin Fry som leder. Musikken kan ABC BEAUTY STAB 1983 MERCURY 814 661-1 GER LP høres som en mix av Bowie og Roxy Music. Mick fra den første utgaven av Jethro Tull og Blodwyn Pig med sitt soloalbum fra ABRAHAMS, MICK MICK ABRAHAMS 1971 A&M RECORDS SP 4312 USA LP 1971. Drivende god blues / prog rock. Min første og eneste skive med det tyske heavy metal bandet. Et absolutt godt ACCEPT RESTLESS AND WILD 1982 BRAIN 0060.513 GER LP album, med Udo Dirkschneider på hylende vokal. Fikk opplevd Udo og sitt band live på Byscenen i Trondheim november 2017. Meget overraskende og positiv opplevelse, med knallsterke gitarister, og sønnen til Udo på trommer. AC/DC HIGH VOLTAGE 1975 ATL 50257 GER LP Debuten til hardrocker'ne fra Down Under. AC/DC POWERAGE 1978 ATL 50483 GER LP 6.albumet i rekken av mange utgivelser. ACKLES, DAVID AMERICAN GOTHIC 1972 EKS-75032 USA LP Strålende låtskriver, albumet produsert av Bernie Taupin, kompisen til Elton John. GEFFEN RECORDS AEROSMITH PUMP 1989 EUR LP Steven Taylor, Joe Perry, Tom Hamilton, Joey Kramer. Spilt inn i Canada. 924254 AKKERMAN, JAN PROFILE 1972 HARVEST SHSP 4026 UK LP Soloalbum fra den glimrende gitaristen fra nederlandske progbandet Focus. Akkermann med klassisk gitar, lutt og et stor orkester til hjelp. I tillegg rockere som AKKERMAN, JAN TABERNAKEL 1973 ATCO SD 7032 USA LP Tim Bogert bass og Carmine Appice trommer. Her viser Akkermann en ny side av sitt talent. -

Grateful Dead

STORIES STORIES UNTOLD—The Very Best of Stories They had a #1 hit and one of the most enduring (and controversial) hits of the ‘70s in “Brother Louie”—the groundbreaking song about an interracial love affair recently heard (in a re-recorded version) as the theme song of SELLING POINTS: Louis C.K.’s hit TV series Louie—but Stories have never had any kind of collection devoted to their work. One reason for that might be that the • Led by Ian Lloyd and Michael Brown band had two distinct eras: the first two albums with Ian Lloyd and the (Formerly of the Left Banke), Stories Left Banke’s Michael Brown as co-leaders of the band, and the third and Released Three Excellent Albums and final album with Lloyd as the sole frontman. Which we have kept in mind Scored Five Chart Hits During the ‘70s in putting together in this compilation, which features four single sides Including the #1 Hit “Brother Louie” that have never been on CD. Stories Untold starts with the “Two by • Stories Untold Is the First-Ever Compilation Two (I’m Losing You)”/”Love Songs in the Night” single taken from the of Their Work Ultra Violet’s Hot Parts soundtrack that was purportedly recorded by the Left Banke but was credited to Steve Martin, who was a founding member of that group along with Brown. We also include • Includes 19 Tracks Taken from Three the solo singles that Brown and Lloyd released on the Kama Sutra and Scotti Bros. labels, respectively. But Albums and Hit Singles Plus Solo Work by at the heart of the collection are the songs the band released as Stories and Ian Lloyd & Stories—the original Lloyd and Brown hit single versions of “Brother Louie,” “I’m Coming Home,” “Darling,” “Mammy Blue” and “If It Feels Good, Do • Features Four Single Sides Making Their It,” plus key album tracks, all remastered at Sony’s Battery Studios in New York. -

On Bach's Bottomby Alex Chilton

On Bach’s Bottom by Alex Chilton Elizabeth Barker Not too many years ago, I stole a rock star’s likeness for my novel and then he asked me on a date. He’s the singer for a band I’ve loved since I was 14, one of the most enduring infatuations of my life. The character I based on him was very minor: my protagonist’s most adored ex-boyfriend, who wore beaded necklaces and ate his ice cream from the pint, with a butter knife instead of a spoon. He existed in flashbacks where kids drank Alex Chilton warm beer on back porches in the New England summertime, Rickie Lee Jones on the Bach’s Bottom radio. In one scene he dragged his finger through the melted frosting of a lemon danish, on a front stoop on a Sunday morning when he and his girl had barely slept and both had 1981 exciting hair, unwashed and ocean-salty. Line Records There wasn’t much point in adding that character to the story. I mostly stole the singer’s likeness so that I could infuse some of his goofball aura into my book. His aura was the exact sunny-yellow of the nucleus of a lemon danish, and I wanted to use him like a filmmaker uses pop songs to siphon off the sentiment of the melody. A few months after I wrote that section of my book, the singer moved to Los Angeles, to my side of town. And it unthrills me to get to this part of the story, because no one ever wants to use the word Twitter when they’re talking about love—but I suppose that’s the reality of the world today. -

Photo Needed How Little You

HOW LITTLE YOU ARE For Voices And Guitars BY NICO MUHLY WORLD PREMIERE PHOTO NEEDED Featuring ALLEGRO ENSEMBLE, CONSPIRARE YOUTH CHOIRS Nina Revering, conductor AUSTIN CLASSICAL GUITAR YOUTH ORCHESTRA Brent Baldwin, conductor HOW LITTLE YOU ARE BY NICO MUHLY | WORLD PREMIERE TEXAS PERFORMING ARTS PROGRAM: PLEASESEEINSERTFORTHEFIRSTHALFOFTHISEVENING'SPROGRAM ABOUT THE PROGRAM Sing Gary Barlow & Andrew Lloyd Webber, arr. Ed Lojeski From the first meetings aboutHow Little Renowned choral composer Eric Whitacre You Are, the partnering organizations was asked by Disney executives in 2009 Powerman Graham Reynolds knew we wanted to involve Conspirare to compose for a proposed animated film Youth Choirs and Austin Classical Guitar based on Rudyard Kipling’s beautiful story Libertango Ástor Piazzolla, arr. Oscar Escalada Youth Orchestra in the production and are The Seal Lullaby. Whitacre submitted this Austin Haller, piano delighted that they are performing these beautiful, lyrical work to the studios, but was works. later told that they decided to make “Kung The Seal Lullaby Eric Whitacre Fu Panda” instead. With its universal message issuing a quiet Shenandoah Traditional, arr. Matthew Lyons invitation, Gary Barlow and Andrew Lloyd In honor of the 19th-century American Webber’s Sing, commissioned for Queen poetry inspiring Nico Muhly’s How Little That Lonesome Road James Taylor & Don Grolnick, arr. Matthew Lyons Elizabeth’s Diamond Jubilee in 2012, brings You Are, we chose to end the first half with the sweetness of children’s voices to brilliant two quintessentially American folk songs Featuring relief. arranged for this occasion by Austin native ALLEGRO ENSEMBLE, CONSPIRARE YOUTH CHOIRS Matthew Lyons. The haunting and beautiful Nina Revering, conductor Powerman by iconic Austin composer Shenandoah precedes James Taylor’s That Graham Reynolds was commissioned Lonesome Road, setting the stage for our AUSTIN CLASSICAL GUITAR YOUTH ORCHESTRA by ACG for the YouthFest component of experience of Muhly’s newest masterwork. -

Alex Chilton By:Dave Hoekstra Jan

Alex Chilton by:Dave Hoekstra Jan. 30, 1994 The pairing of Alex Chilton and Ben Vaughn is a natural. Each is a terrifically perceptive songwriter, influenced by the wonder of 1960s AM radio, but stimulated by the challenge of reinvention in the 1990s. Chilton, 42, grew up in Memphis, Tenn., where he played in the Box Tops from 1967-70 and the celebrated Big Star from 1971-74. Chilton's songs have been recorded by the Bangles, R.E.M. and the Replacements, who paid homage with the hit tune "Alex Chilton." Besides working as a songwriter, he has been a cabbie and a dishwasher, and last year, took part in an acclaimed Big Star reunion. Vaughn, 38, was borm in Camden, N.J. Marshall Crenshaw had a hit with Vaughn's "I'm Sorry (But So Is Brenda Lee)," and the Skeletons dipped into the Vaughn songbag for "I Dig Your Wig" and "Lookin' for a 7-11." Vaughn is a passionate American musicologist, having compiled and annotated "Johnny Otis: The Capitol Years," and last year, produced the late Arthur Alexander's "Lonely Just Like Me." Besides being a songwriter, he's been a landscaper and a dishwasher. His new record is "Mono U.S.A." (Bar None Records). Chilton and Vaughn met in the mid-1980s, when they did some Midwestern dates together, and now the Ben Vaughn Combo will open for Chilton Friday at Metro.[Editors note: the cover was only $4!] Chilton and Vaughn plan to collaborate on some new songs. On a conference call last week, Chilton and Vaughn discussed the craft of songwriting. -

A Cypress Is Gone

Louisiana Law Review Volume 80 Number 2 Winter 2020 Article 7 4-22-2020 A Cypress is Gone Thomas C. Galligan Louisiana State University Law Center, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.lsu.edu/lalrev Part of the Law Commons Repository Citation Thomas C. Galligan, A Cypress is Gone, 80 La. L. Rev. (2020) Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.lsu.edu/lalrev/vol80/iss2/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews and Journals at LSU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Louisiana Law Review by an authorized editor of LSU Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Cypress Is Gone Thomas C. Galligan* In my metaphorical forest of torts scholars, there are many tall and strong trees, reaching with their scholarship and teaching to the sky. Some are oaks—strong and traditional; some are maples—with wide leaves. Others—the Californians—are sequoias. But some—a remarkable number, really—are a bit different: they reach to the sky but spring from water. They are the Louisianans. They are cypress trees, and one of the most beautiful and resilient of those cypress trees is gone—Dave Robertson. Professor David W. Robertson of the University of Texas School of Law passed away late in 2018 after courageously and quietly battling cancer. Dave was certainly a Texan, having spent the vast majority of his many years of teaching at UT, but he also was a Louisianan. As he humbly and humorously described himself, he was “one of the best lawyers to ever come out of Pollock, Louisiana.” He was a graduate of the Louisiana State University Law School, Class of 1961; he taught here both as a full-time faculty member and as a visitor, and he was a frequent speaker at LSU and other Louisiana continuing legal education programs. -

In BLACK CLOCK, Alaska Quarterly Review, the Rattling Wall and Trop, and She Is Co-Organizer of the Griffith Park Storytelling Series

BLACK CLOCK no. 20 SPRING/SUMMER 2015 2 EDITOR Steve Erickson SENIOR EDITOR Bruce Bauman MANAGING EDITOR Orli Low ASSISTANT MANAGING EDITOR Joe Milazzo PRODUCTION EDITOR Anne-Marie Kinney POETRY EDITOR Arielle Greenberg SENIOR ASSOCIATE EDITOR Emma Kemp ASSOCIATE EDITORS Lauren Artiles • Anna Cruze • Regine Darius • Mychal Schillaci • T.M. Semrad EDITORIAL ASSISTANTS Quinn Gancedo • Jonathan Goodnick • Lauren Schmidt Jasmine Stein • Daniel Warren • Jacqueline Young COMMUNICATIONS EDITOR Chrysanthe Tan SUBMISSIONS COORDINATOR Adriana Widdoes ROVING GENIUSES AND EDITORS-AT-LARGE Anthony Miller • Dwayne Moser • David L. Ulin ART DIRECTOR Ophelia Chong COVER PHOTO Tom Martinelli AD DIRECTOR Patrick Benjamin GUIDING LIGHT AND VISIONARY Gail Swanlund FOUNDING FATHER Jon Wagner Black Clock © 2015 California Institute of the Arts Black Clock: ISBN: 978-0-9836625-8-7 Black Clock is published semi-annually under cover of night by the MFA Creative Writing Program at the California Institute of the Arts, 24700 McBean Parkway, Valencia CA 91355 THANK YOU TO THE ROSENTHAL FAMILY FOUNDATION FOR ITS GENEROUS SUPPORT Issues can be purchased at blackclock.org Editorial email: [email protected] Distributed through Ingram, Ingram International, Bertrams, Gardners and Trust Media. Printed by Lightning Source 3 Norman Dubie The Doorbell as Fiction Howard Hampton Field Trips to Mars (Psychedelic Flashbacks, With Scones and Jam) Jon Savage The Third Eye Jerry Burgan with Alan Rifkin Wounds to Bind Kyra Simone Photo Album Ann Powers The Sound of Free Love Claire -

HOUSE JOINT RESOLUTION 1023 by Coley a RESOLUTION to Honor

HOUSE JOINT RESOLUTION 1023 By Coley A RESOLUTION to honor the memory of legendary musician and songwriter Alex Chilton. WHEREAS, it is fitting that this General Assembly should honor the memory of a legendary entertainer, artist, and permanent fixture of American music, Alex Chilton; and WHEREAS, an accomplished musical icon, Alex Chilton was a folk troubadour, blues singer, songwriter, guitarist, master musician, voice of a generation, and godfather of American indie-rock, whose influence has been felt by generations of artist, musicians, and loyal fans; and WHEREAS, born in Memphis, Tennessee, on November 28, 1950, his musical destiny was shaped by the influence of his father, Sidney Chilton, a popular Memphis jazz musician; and WHEREAS, taking up guitar at age thirteen, he was recognized early on for his soulful voice and distinctive style, and as a teenager in 1966, Alex Chilton was asked to join the Devilles, a popular local Memphis band; and WHEREAS, building on their tremendous local popularity, the group was renamed the Box Tops and began to perform nationally with sixteen-year-old Alex Chilton as the lead singer; and WHEREAS, combining elements of soul music and light pop, the Box Tops enjoyed a hit single “The Letter,” which reached number one on the charts in the U.S. and abroad in 1967, and was followed by several other major chart toppers, including “Cry Like a Baby” in 1968, and “Soul Deep” in 1969; and WHEREAS, in early 1970, the members of the Box Tops decided to disband and pursue independent careers, and after moving to New York City, Mr. -

Big Stars Radio City Free Download

BIG STARS RADIO CITY FREE DOWNLOAD Bruce Eaton | 144 pages | 01 Jul 2009 | Bloomsbury Publishing PLC | 9780826428981 | English | London, United Kingdom Guitar sound on Big Star's 'Radio City' Saturday 9 May Add a Comment. Monday 27 July Archived from the original on April 28, Monday 12 October Saturday 11 July Learn more. Best Ever Albums top by rabaier. Start the wiki. Contributors lunareclipserecordsrarityvaluerhythmoflife. Saturday 19 September Wednesday 9 September Archived from the original on December 11, Classic RecordsArdent Records 2. Tuesday 13 October Download as PDF Printable version. She's a Mover Alex Chilton. A1 is in mono, the Big Stars Radio City in stereo. Tuesday 16 June Archived from the original on November 29, Friday 26 June Drinking Hanging Out In Love. Friday 31 July I Big Stars Radio City the guitars mattered too, 'cause I could hear what I was hearing--there's Big Stars Radio City tone, and then there's also a certain way Alex attacks the string, sorta coming down and digging or plucking at the string instead of just picking it with a back-and-forth wrist motion. Sunday Big Stars Radio City September Wednesday 7 October Categories : Big Star albums Ardent Records albums albums. My definitive copy. StaxArdent Records 2Akarma. Saturday 25 July More Images. Saturday 26 September I'm going to keep the vinyl and sell the other goodies. Monday 11 May Tracklist Sorted by: Running order Running order Most popular. Saturday 20 June Views Read Edit View history. Big Star. Though not a commercial success at the Big Stars Radio City, it is now recognized as a milestone album in the history of power pop music.