Mto.04.10.4.W Everet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs No. Interpret Title Year of release 1. Bob Dylan Like a Rolling Stone 1961 2. The Rolling Stones Satisfaction 1965 3. John Lennon Imagine 1971 4. Marvin Gaye What’s Going on 1971 5. Aretha Franklin Respect 1967 6. The Beach Boys Good Vibrations 1966 7. Chuck Berry Johnny B. Goode 1958 8. The Beatles Hey Jude 1968 9. Nirvana Smells Like Teen Spirit 1991 10. Ray Charles What'd I Say (part 1&2) 1959 11. The Who My Generation 1965 12. Sam Cooke A Change is Gonna Come 1964 13. The Beatles Yesterday 1965 14. Bob Dylan Blowin' in the Wind 1963 15. The Clash London Calling 1980 16. The Beatles I Want zo Hold Your Hand 1963 17. Jimmy Hendrix Purple Haze 1967 18. Chuck Berry Maybellene 1955 19. Elvis Presley Hound Dog 1956 20. The Beatles Let It Be 1970 21. Bruce Springsteen Born to Run 1975 22. The Ronettes Be My Baby 1963 23. The Beatles In my Life 1965 24. The Impressions People Get Ready 1965 25. The Beach Boys God Only Knows 1966 26. The Beatles A day in a life 1967 27. Derek and the Dominos Layla 1970 28. Otis Redding Sitting on the Dock of the Bay 1968 29. The Beatles Help 1965 30. Johnny Cash I Walk the Line 1956 31. Led Zeppelin Stairway to Heaven 1971 32. The Rolling Stones Sympathy for the Devil 1968 33. Tina Turner River Deep - Mountain High 1966 34. The Righteous Brothers You've Lost that Lovin' Feelin' 1964 35. -

Grateful Dead

STORIES STORIES UNTOLD—The Very Best of Stories They had a #1 hit and one of the most enduring (and controversial) hits of the ‘70s in “Brother Louie”—the groundbreaking song about an interracial love affair recently heard (in a re-recorded version) as the theme song of SELLING POINTS: Louis C.K.’s hit TV series Louie—but Stories have never had any kind of collection devoted to their work. One reason for that might be that the • Led by Ian Lloyd and Michael Brown band had two distinct eras: the first two albums with Ian Lloyd and the (Formerly of the Left Banke), Stories Left Banke’s Michael Brown as co-leaders of the band, and the third and Released Three Excellent Albums and final album with Lloyd as the sole frontman. Which we have kept in mind Scored Five Chart Hits During the ‘70s in putting together in this compilation, which features four single sides Including the #1 Hit “Brother Louie” that have never been on CD. Stories Untold starts with the “Two by • Stories Untold Is the First-Ever Compilation Two (I’m Losing You)”/”Love Songs in the Night” single taken from the of Their Work Ultra Violet’s Hot Parts soundtrack that was purportedly recorded by the Left Banke but was credited to Steve Martin, who was a founding member of that group along with Brown. We also include • Includes 19 Tracks Taken from Three the solo singles that Brown and Lloyd released on the Kama Sutra and Scotti Bros. labels, respectively. But Albums and Hit Singles Plus Solo Work by at the heart of the collection are the songs the band released as Stories and Ian Lloyd & Stories—the original Lloyd and Brown hit single versions of “Brother Louie,” “I’m Coming Home,” “Darling,” “Mammy Blue” and “If It Feels Good, Do • Features Four Single Sides Making Their It,” plus key album tracks, all remastered at Sony’s Battery Studios in New York. -

Naperville Jaycees' Last Fling Offers National and Local Musical Acts On

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: June 7, 2019 Contact: Karen Coleman 630.362.6683 [email protected] Naperville Jaycees’ Last Fling Offers National and Local Musical Acts on Two Stages! Naperville, IL – The Naperville Jaycees is proud to announce their full musical lineup for the Main Stage and Jackson Avenue Block Party Stage for the 2019 Last Fling. The Last Fling takes place all along the Riverwalk in Downtown Naperville over all 4 days of Labor Day weekend. “This year’s event will feel a lot more like your typical music festival. We decided to open the Main Stage gates earlier than most previous years to give patrons an opportunity to enjoy music throughout the day and allow them to come and go as they please. I really feel as if we have a solid line up this year and I hope that the community will come out, have some fun and help raise some money with us at the 2019 Last Fling,” says Entertainment Co-Chair Danielle Tufano. 2019 Main Stage Acts: The Last Fling Main Stage will start rocking on Friday night (August 30) with headliner Better Than Ezra. Before their omnipresent 1995 single “Good” hit No. 1, before their debut album Deluxe went double-platinum, before popular shows such as Desperate Housewives licensed their song “Juicy,” before Taylor Swift attested to their timeless appeal by covering their track “Breathless” — New Orleans’ Better Than Ezra was a pop-rock act paying its dues, traveling from town to town in a ramshackle van. Over two decades after the band formed, that vigilance still resonates strongly with the trio, who were finally rewarded after seven years of stubbornly chasing their dreams. -

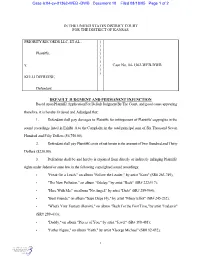

RIAA/Defreese/Proposed Default Judgment and Permanent Injunction

Case 6:04-cv-01362-WEB -DWB Document 10 Filed 08/18/05 Page 1 of 2 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF KANSAS PRIORITY RECORDS LLC, ET AL., ) ) ) Plaintiffs, ) ) ) v. ) Case No. 04-1362-WEB-DWB ) ) KELLI DEFREESE, Defendant. DEFAULT JUDGMENT AND PERMANENT INJUNCTION Based upon Plaintiffs' Application For Default Judgment By The Court, and good cause appearing therefore, it is hereby Ordered and Adjudged that: 1. Defendant shall pay damages to Plaintiffs for infringement of Plaintiffs' copyrights in the sound recordings listed in Exhibit A to the Complaint, in the total principal sum of Six Thousand Seven Hundred and Fifty Dollars ($6,750.00). 2. Defendant shall pay Plaintiffs' costs of suit herein in the amount of Two Hundred and Thirty Dollars ($230.00). 3. Defendant shall be and hereby is enjoined from directly or indirectly infringing Plaintiffs' rights under federal or state law in the following copyrighted sound recordings: C "Freak On a Leash," on album "Follow the Leader," by artist "Korn" (SR# 263-749); C "The New Pollution," on album "Odelay," by artist "Beck" (SR# 222-917); C "Here With Me," on album "No Angel," by artist "Dido" (SR# 289-904); C "Best Friends," on album "Supa Dupa Fly," by artist "Missy Elliot" (SR# 245-232); C "What's Your Fantasy (Remix)," on album "Back For the First Time," by artist "Ludacris" (SR# 289-433); C "Daddy," on album "Pieces of You," by artist "Jewel" (SR# 198-481); C "Father Figure," on album "Faith," by artist "George Michael" (SR# 92-432); 1 Case 6:04-cv-01362-WEB -DWB Document -

In BLACK CLOCK, Alaska Quarterly Review, the Rattling Wall and Trop, and She Is Co-Organizer of the Griffith Park Storytelling Series

BLACK CLOCK no. 20 SPRING/SUMMER 2015 2 EDITOR Steve Erickson SENIOR EDITOR Bruce Bauman MANAGING EDITOR Orli Low ASSISTANT MANAGING EDITOR Joe Milazzo PRODUCTION EDITOR Anne-Marie Kinney POETRY EDITOR Arielle Greenberg SENIOR ASSOCIATE EDITOR Emma Kemp ASSOCIATE EDITORS Lauren Artiles • Anna Cruze • Regine Darius • Mychal Schillaci • T.M. Semrad EDITORIAL ASSISTANTS Quinn Gancedo • Jonathan Goodnick • Lauren Schmidt Jasmine Stein • Daniel Warren • Jacqueline Young COMMUNICATIONS EDITOR Chrysanthe Tan SUBMISSIONS COORDINATOR Adriana Widdoes ROVING GENIUSES AND EDITORS-AT-LARGE Anthony Miller • Dwayne Moser • David L. Ulin ART DIRECTOR Ophelia Chong COVER PHOTO Tom Martinelli AD DIRECTOR Patrick Benjamin GUIDING LIGHT AND VISIONARY Gail Swanlund FOUNDING FATHER Jon Wagner Black Clock © 2015 California Institute of the Arts Black Clock: ISBN: 978-0-9836625-8-7 Black Clock is published semi-annually under cover of night by the MFA Creative Writing Program at the California Institute of the Arts, 24700 McBean Parkway, Valencia CA 91355 THANK YOU TO THE ROSENTHAL FAMILY FOUNDATION FOR ITS GENEROUS SUPPORT Issues can be purchased at blackclock.org Editorial email: [email protected] Distributed through Ingram, Ingram International, Bertrams, Gardners and Trust Media. Printed by Lightning Source 3 Norman Dubie The Doorbell as Fiction Howard Hampton Field Trips to Mars (Psychedelic Flashbacks, With Scones and Jam) Jon Savage The Third Eye Jerry Burgan with Alan Rifkin Wounds to Bind Kyra Simone Photo Album Ann Powers The Sound of Free Love Claire -

On the Beat Calderone School of Music

A WATCHUNG COMMUNICATIONS, INC. PUBLICATION The Westfield Leader and THE TIMES of Scotch Plains – Fanwood Thursday, October 10, 2002 Page 21 Peter Gabriel’s ‘Up’ Is Downer; But Indies Don’t Disappoint Arts & Entertainment By ANDY GOLDENBERG happening. Specially Written for The Westfield Leader and The Times Universal Music sent some good As fall arrives, the quantity of CD reissue material beginning with a two- Pen & Ink releases continues unabated. disc Deluxe Edition of The Who’s CONTINUED FROM PAGE 22 Beginning with his first album in “My Generation” album complete and make trouble,” encouraged about 30 (well, 10) years by Peter with bonus material and the sound Sarandon, who coincidentally has Gabriel, “Up” on Geffen Records is quality is extraordinary. Also from not as much a return to Universal come great a movie coming out this month. form as it is a continua- compilations of “Kiss” As inappropriate as the enter- tion of form from his last and “T-Rex.” tainment industry’s desperate album “Us.” Some smaller labels The moody keyboard have put out some great scramble to stage a 9/11 sounds abound, there is a reissue and new material fundraiser (which I’m still con- lot of dark lyrical imag- beginning with Cunei- vinced was done to keep the peace ery. While the themes of form Records out of the last album dealt with Maryland. Known for the between their pocketbooks and relationships, “Up” deals devotion to Progressive their adoring fans), it is equally more with the finality and Rock, Cuneiform has just improper for celebrities to get fragility of life. -

December 6) 1999

VOLUME 33 The season to b e jolly: December 6, Author Frank McCourt con tinues the au~obiographical 1999 story he began in "Angela's Ashes" in the new book ISSUE 973 "'Tis. " ..... See pages 6-7 http://WlNlN.ulnsl.edu/studen"tli fe/curreni: UNIVERSITV O F MIS SOURI - S T. LOUIS Faculty'Council demands -.. III D: more involvement in ·cGI . .cIII c. decision-making process GI iii BY BRIAN DOUGLAS "In order to restore the cOIili ., .• . ,. , . , q ., ... , . ... ,., .. .".,., . ",. " . ..•. ,.. of The Current staff dence of the faculty in her adminis tration, Chancellor Toullill must In response to Chancellor inlplemem steps to meaningfully Blanche Touhill's fonnation of a task involve the faculty in the campus' force for campus-wide strategic planning and governance. At future planning, the Faculty Council passed meetings the Faculty CoUl)cil will a motion Thursday which reiterated consider whether effective steps its call for greater faculty involve have been taken," the motion said, ment in the planning and decision Judd acknowledged that the making process. motion was not satis Dennis Judd, pre factory to all members siding officer of the of the council. Faculty Council, Criticism of the described the motion motion ranged from as a middle-ground statements that it was Gary Grace, vice chancellor for student affairs, explains the new policy for overdue stUdent proposal. Previously, too harshly worded to accounts to Tilly lashel, a junior. Judd had expressed the complaints that it was view that the faculty's overly vague. confidence ill The fOlmation of Chancellor Touhill the Chancellor's task Administrators want to was so badly marred Touhill force followed the that a change in leader recent controversy ship might be the only over a system-level way to resolve the situ audit of UM-St. -

Diplo and Beck Confirmed for Northside

Diplo 2017-12-01 09:59 CET Diplo and Beck confirmed for NorthSide Thundercat, Rhye, and Jimmy Eat World will also appear at next year's festival This year’s last round of announcements for NorthSide 2018 will significantly expand the festival’s musical spectrum and offer everything from baile funk and sophisticated electronica to fusion jazz and postmodern disco-funk. Over the last three years, Diplo has been unavoidable because of global megahits like “Lean On”, "Where Are Ü Now", and “Cold Water”. He has found chart success as a producer for M.I.A., Sia, and Beyoncé, as a member of Major Lazer and Jack Ü and as solo artist, and he is always highly ranked on DJ Mag's list of the world’s best dj’s. The productive producer’s unique take on baile funk has made its mark on charts throughout the world since the breakthrough with "Paper Planes", and as he himself put it a few years ago; Random White Dude Be Everywhere. This summer that will for the first time also include NorthSide. Diplo will play Saturday June 9th at NorthSide 2018 Earlier this year, the always unpredictable Beck released the album "Colors", which picked up the thread from the dance-friendly and fun album from 1999, “Midnite Vultures”. Through a long and ever changing career, he has sold millions of records, won Grammys, and impressed with masterpieces such as "Odelay" and most recently the understated "Morning Phase". But the acoustic guitar has taken the backseat on new songs like "Dreams" and "Wow" and the focus is now instead on getting people back on the dance floor. -

Vertical Horizon to Headline 34 Annual Pelham Medical

OFFICIAL MEDIA RELEASE Media Contact Katie Witherspoon April 5, 2018 Vice President of Operations Greer Chamber of Commerce FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE 864.877.3131, ext. 102 VERTICAL HORIZON TO HEADLINE 34TH ANNUAL PELHAM MEDICAL CENTER GREER FAMILY FEST (Greer, SC) It’s everything you want. It’s everything you need. It’s the 34th annual Pelham Medical Center Greer Family Fest, featuring 90s superstars Vertical Horizon as the headline performer for 2018. “We are excited to bring Vertical Horizon to Greer, and look forward to a great weekend!” said festival Chairman Brent Garrett. The festival happens throughout downtown Greer and Greer City Park on Friday, May 4 and Saturday, May 5. Vertical Horizon will perforM a free concert Saturday, May 5, 2018 at 8 p.M. in Greer City Park. Pelham Medical Center returns as the event’s title sponsor. The City of Greer also returns as the festival’s presenting sponsor. ABOUT GREER FAMILY FEST With a rich history of providing family fun for all ages, the annual Pelham Medical Center Greer Family Fest promises to be better than ever this year, the 34th anniversary of the event. This year's event will feature the best of the old and add exciting new activities, with the goal of being the Upstate's favorite family festival. This two-day event features live music on the CBL State Savings Bank Main Stage and the Family Dental Health Community Stage, Mitsubishi Anne Helton Creation Station, Apple Seeds Pediatric Dentistry & Carolina Family Orthodontics KidsZone, Greer CPW Rudy’s Restaurant Row, and more than 150 vendors throughout the festival. -

Vertical Horizon, Strol(E 9 Piay House of Blues

ARTS & ENTERTAINMENT 18__________________February 23,2000 • the Seahawk Vertical Horizon, Strol(e 9 piay House of Blues Do you have an by KRISTI SINGER__________ Stroke 9 was toned-down compared to Cup dressed in rock star attire with purple shiny Staff Writer cakes, with rhythm that was easier to dance shirts and black leather pants. VH was burst event or perfor to. ing with positive energy. Vertical Horizon headlined at the House Stroke 9 played titles from their Cherry/ “It’s great to be here. What a beautiful mance that you of Blues, Myrtle Beach, SC on Feb. 12 with Universal debut album. Nasty Little audience,” vocalist Matthew Scannell said guest performers Stroke 9 and Cupcakes. Thoughts, including “City Life,” which vo to the fans. would like to see ir Cupcakes began roughly at 7:30 p.m. calist Luke Esterkyn said was about living VH performed songs from their TASK grabbing the audience with their eccentric in the city in an overpriced apartment. Records/RCA Records album. Everything the Seahawk? attire of bright orange space suits (like the “This song is about working really hard You Want, including their hits “We Are” and Beastie Boys wear in the “Intergalactic” for things in your life and not waiting for “Everything You Want.” They also per video) and sunglasses that had red laser them to happen,” Esterkyn said right before formed a new song, titled “The Glass Waltz.” pointers over one eye. They brought an un they played “Tale of the Sun,” which the Vertical concluded their set with “We Call Megan O’Brien earthly presence to the stage. -

Guns N' Roses in Spain

Backstage Pass Volume 2 Issue 1 Article 2 2019 Guns N' Roses in Spain Ailey L. Butler University of the Pacific, [email protected] Ailey is a music industry major at UOP. She is hoping to break into the live music/touring scene of the music industry after being passionate about music her whole life. ...Read More This article was written as part of the curriculum for the Bachelor of Music in Music Management and the Bachelor of Science in Music Industry Studies at University of the Pacific. Each student conducted research based on his or her own areas of interest and study. To learn more about the program, visit: go.pacific.edu/musicindustry All images used from album covers are included under the Fair Use provision of U.S. Copyright law and remain the property of their respective copyright owners. Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.pacific.edu/backstage-pass Part of the Arts Management Commons, Music Performance Commons, and the Radio Commons Recommended Citation Butler, Ailey L. (2019) "Guns N' Roses in Spain," Backstage Pass: Vol. 2 : Iss. 1 , Article 2. Available at: https://scholarlycommons.pacific.edu/backstage-pass/vol2/iss1/2 This Concert and Album Review is brought to you for free and open access by the Conservatory of Music at Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Backstage Pass by an authorized editor of Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Butler: Guns N' Roses in Spain Guns N’ Roses in Spain By Ailey Butler This concert was held on July 1st, 2018 in Barcelona at the Estadi Olímpic Lluís Companys. -

Mediamonkey Filelist

MediaMonkey Filelist Track # Artist Title Length Album Year Genre Rating Bitrate Media # Local 1 Kirk Franklin Just For Me 5:11 2019 Gospel 182 Disk Local 2 Kanye West I Love It (Clean) 2:11 2019 Rap 4 128 Disk Closer To My Local 3 Drake 5:14 2014 Rap 3 128 Dreams (Clean) Disk Nellie Tager Local 4 If I Back It Up 3:49 2018 Soul 3 172 Travis Disk Local 5 Ariana Grande The Way 3:56 The Way 1 2013 RnB 2 190 Disk Drop City Yacht Crickets (Remix Local 6 5:16 T.I. Remix (Intro 2013 Rap 128 Club Intro - Clean) Disk In The Lonely I'm Not the Only Local 7 Sam Smith 3:59 Hour (Deluxe 5 2014 Pop 190 One Disk Version) Block Brochure: In This Thang Local 8 E40 3:09 Welcome to the 16 2012 Rap 128 Breh Disk Soil 1, 2 & 3 They Don't Local 9 Rico Love 4:55 1 2014 Rap 182 Know Disk Return Of The Local 10 Mann 3:34 Buzzin' 2011 Rap 3 128 Macc (Remix) Disk Local 11 Trey Songz Unusal 4:00 Chapter V 2012 RnB 128 Disk Sensual Local 12 Snoop Dogg Seduction 5:07 BlissMix 7 2012 Rap 0 201 Disk (BlissMix) Same Damn Local 13 Future Time (Clean 4:49 Pluto 11 2012 Rap 128 Disk Remix) Sun Come Up Local 14 Glasses Malone 3:20 Beach Cruiser 2011 Rap 128 (Clean) Disk I'm On One We the Best Local 15 DJ Khaled 4:59 2 2011 Rap 5 128 (Clean) Forever Disk Local 16 Tessellated Searchin' 2:29 2017 Jazz 2 173 Disk Rahsaan 6 AM (Clean Local 17 3:29 Bleuphoria 2813 2011 RnB 128 Patterson Remix) Disk I Luh Ya Papi Local 18 Jennifer Lopez 2:57 1 2014 Rap 193 (Remix) Disk Local 19 Mary Mary Go Get It 2:24 Go Get It 1 2012 Gospel 4 128 Disk LOVE? [The Local 20 Jennifer Lopez On the