Sir William Lawrence (1783-1867): a Study of Pre-Darwinian Ideas on Heredity and Variation Author(S): Kentwood D

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Evogenesis.Pdf

EvoGenesis Easy answers to evolution The ultimate answer to evolution and the crisis in creationism John Thomas 1 2 CONTENTS PART 1 EVOGENESIS- THE REAL ORIGIN OF SPECIES 1.1 The Genesis Alternative 1.2 An Overview Of EvoGenesis PART 2 WHERE DARWIN WENT WRONG 2.1 The Darwin Delusion 2.2 Evolution Fails Fossil Test 1 2.3 Evolution Fails Fossil Test 2 2.4 Jean Baptiste Lamarck 2.5 The Origin of Variation 2.6 A Brief History of Complexity 2.7 Complexity Within Complexity 2.8 Every Body Needs a Bauplan 2.9 Neo-Darwinism 2.10 Cuvier the Catastrophist 2.11 The Self-developing Genome 2.12 Another Look at Natural Selection 2.13 The Missing Link 2.14 Faith, Assumption and Dogma 2.15 Darwin's Personal Agenda 2.16 The Birth of Geology 2.17 Rocks & Fossils 2.18 Dinosaurs and Dragons 2.19 Radiometric Dating 2.20 The Curse of Evolution PART 3 A CLOSER LOOK AT THE GENESIS ACCOUNT OF CREATION 3.1 Questions & Answers 3.2 In the Beginning 3.3 Chaos! 3.4 Day One- A Special Light 3.5 Day Two - Waters above & Waters below 3.6 Day Three - The Dry Land, the Sea & Plants 3.7 Day Four - The Sun, the Moon & Stars 3.8 Day Five- Fish & Birds 3.9 Day Six - Cattle, Creeping Things and Beasts 3.10 Day Six - Man 3.11 Day Six- Everything was Good 3.12 Eden 3.13 The Flood of Noah - Some Questions 3.14 The Ark 3.15 The Deluge 3.16 The Aftermath Conclusions 3 4 PREFACE HISTORY REPEATING History, we are told, has a habit of repeating itself. -

Ecological and Evolutionary Dynamics of Aresian and Erosian Economy

International Journal of Industrial Engineering and Management (IJIEM), Vol. 5 No 1, 2014, pp. 1-12 Available online at www.iim.ftn.uns.ac.rs/ijiem_journal.php ISSN 2217-2661 UDK 330.34:316.32 Ecological and Evolutionary Dynamics of Aresian and Erosian Economy Imre Lázár Professor, Károli Gáspár University, Institute of Social Sciences and Communication Studies, Budapest, [email protected] Received (05.12.2013.); Revised (03.03.2014.); Accepted (15.03.2014.) Abstract In this paper we explore the ecodynamics of economic transformation of Central-East –European late socialist industries under the pressure of globalization. We use both term ARES and Eros in allegoric sense and as an acronym of Accumulation, Risk, Environmental degradation In this framework we deconstruct the process of the neoliberal transformation of local economies. Deconstruction of informational, technological and social dynamism also helps to reveal the hierarchical ranks of the four environmental actors feedingt the ARESian dynamics of contemporary economical and social phenomena. Key words: 4T tetrahedron ecodynamic modell, the neoliberal economic turn, diversity 1. INTRODUCTION nonhuman animals and the human history concluding that cooperation and mutual aid is one of the leading Economy is an environmentally and ecologically factors in the survival and the evolution of species. and embedded anthropological system of human the ability to survive. subsistence being liable to harsh ecodynamics of co- evolving actors: nature, social and technological Ecology teaches us that both form is relevant (being contributions, and knowledge. In a holistic frame of usually mixed) in the complex ecodynamics of reference of our MEO model [1] economical evolution ecorelations, nevertheless the one-sided view of appears to be a human ecological drama in the evolutionary logic of competitive vision of global everchanging civilizational stage. -

Evolution, Creationism, and Intelligent Design Kent Greenwalt

Notre Dame Journal of Law, Ethics & Public Policy Volume 17 Article 2 Issue 2 Symposium on Religion in the Public Square 1-1-2012 Establishing Religious Ideas: Evolution, Creationism, and Intelligent Design Kent Greenwalt Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.nd.edu/ndjlepp Recommended Citation Kent Greenwalt, Establishing Religious Ideas: Evolution, Creationism, and Intelligent Design, 17 Notre Dame J.L. Ethics & Pub. Pol'y 321 (2003). Available at: http://scholarship.law.nd.edu/ndjlepp/vol17/iss2/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Notre Dame Journal of Law, Ethics & Public Policy at NDLScholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Notre Dame Journal of Law, Ethics & Public Policy by an authorized administrator of NDLScholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ARTICLES ESTABLISHING RELIGIOUS IDEAS: EVOLUTION, CREATIONISM, AND INTELLIGENT DESIGN KENT GREENAWALT* I. INTRODUCTION The enduring conflict between evolutionary theorists and creationists has focused on America's public schools. If these schools had no need to teach about the origins of life, each side might content itself with promoting its favored worldview and declaring its opponents narrow-minded and dogmatic. But edu- cators have to decide what to teach, and because the Supreme Court has declared that public schools may not teach religious propositions as true, the First Amendment is crucially implicated. On close examination, many of the controversial constitu- tional issues turn out to be relatively straightforward, but others, posed mainly by the way schools teach evolution and by what they say about "intelligent design" theory, push us to deep questions about the nature of science courses and what counts as teaching religious propositions. -

Confessions of the Evolutionists

ver since it was first put forward, certain materialist circles have attempt- ed to portray the theory of evolution as scientific fact. In fact, however, the theory, which claims that life emerged as the result of chance process- es, has been utterly disproved by all branches of science. Over the 150 or so years from the time of Charles Darwin, the founder of the theory, to the present day, scientific fields as palaeontology, biochemistry, genetics and anatomy have de- molished the theory’s assumptions one by one. The more the details of nature have been revealed, the more extraordinary characteristics have been discovered that can never be explained in terms of chance. For all these reasons, in the words of the famous molecular biologist Professor Michael Behe, evolution theory is “A theory in crisis.” This crisis that the theory is in leads scientists who support the theory to make a num- ber of confessions from time to time. These scientists do not reject the theory because of their materialist preconceptions, but they are aware of the fact that the theory conflicts with scientific findings. In this book you will find statements made by these evolutionist scientists regarding the theory they advocate. You will see that even though hundreds of evolutionists, from Charles Darwin to eminent present-day supporters of his theory, such as Richard Dawkins, Stephen Jay Gould and Richard Leakey still advocate this theory, they have admitted that this theory is groundless, incorrect, and even ridiculous. If you want to see that Darwinism is a tale that even Darwinism’s most determined proponents do not believe in, you must read these confessions. -

CRSQ Volume 41

Creation Research Society Quarterly Volume 41 June 2004 Number 1 Articles Departments Helium Diffusion Age of 6,000 Years Photographic Essay: Blood Reserve ................................. 23 Supports Accelerated Nuclear Decay .......................... 1 D. Russell Humphreys, Steven A. Austin, John R. Book Reviews Baumgardner, and Andrew A. Snelling Forbidden Archeology’s Impact Jökullhlaups and Catastrophic Coal Formation .............. 17 by Michael Cremo .............................................. 21 Carl R. Froede Jr. The Man Who Found Time by Jack Repcheck ............ 45 Prey by Michael Crichton .......................................... 68 The Origin of the Brain and Mind ................................... 28 Brad Harrub and Bert Thompson The Never-Ending Story by Antonio Lazcano ............. 78 Dragon Hunter: Roy Chapman Andrews Mind, Materialism, and Consciousness........................... 46 Brad Harrub and Bert Thompson and the Central Asiatic Expeditions by Charles Gallenkamp....................................... 83 The Unbridgeable Chasm Between Microevolution and Macroevolution .................................................. 60 Letters to the Editor ........................................................80 Jerry Bergman Instructions to Authors ....................................................85 Notes from the Panorama of Science Membership/Subscription Application and Renewal Form ..........................................................87 Extrapolations from Humphreys’ Geomagnetic Data Reinforce His Young -

Blog Booklet

Synthetic Biology and Responsible language Use An Anthology of Blog Posts Brigitte Nerlich 4/8/2016 This booklet contains blog posts published between 2014 and 2016 as part of the work undertaken for the BBSRC/EPSRC funded Synthetic Biology Research Centre, University of Nottingham TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword 1. History of synthetic biology Fermenting thought: A new look at synthetic biology 2. Advances in synthetic biology Making synthetic biology public: The case of XNAS and Xnazymes 3. Responsible language use and metaphors Synthetic biology, metaphors and ethics The book of life: Reading, writing, editing Gene editing, metaphors and responsible language use On the metaphorical origin of gene drives On books, circuits and life Precision metaphors in a messy biological world CRISPR hype A programming language for living cells 4. Synthetic biology, the media and the bioeconomy Synthetic biology markets: Opportunities and obstacles The bioeconomy in the news - or not 5. Responsible innovation and synthetic biology Making synthetic biology public From recombinant DNA to gene editing: A history of responsible innovation (including an appendix listing many subsequent articles and discussions on gene editing) Ta(l)king responsibility Pathways in Science and Society Acceleration, autonomy and responsibility 6. More general reflections on Responsible Research and Innovation Responsible innovation: Great expectations, great responsibilities RRI and impact: An impossiblist agenda for research? 7. Miscellaneous Advanced fermenters Synthetic biology or the modern Prometheus Natural/artificial The colours of biotechnology Synthetic biology comes to Nottingham 1 FOREWORD Synthetic biology is a rapidly maturing area of research which can be described as the design and construction of novel artificial biological pathways, organisms or devices. -

Science for All

SCIENCE FOR ALL Science for All :::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: The Popularization of Science in Early Twentieth-Century Britain PETER J. BOWLER The University of Chicago Press : Chicago and London Peter J. Bowler is professor of history of science in the School of History and Anthropology at Queen’s University, Belfast. He is the author of several books, including with the University of Chicago Press: Life’s Splendid Drama: Evolutionary Biology and the Reconstruction of Life’s Ancestry, 1860–1940 and Reconciling Science and Religion: The Debate in Early-Twentieth-Century Britain; and coauthor of Making Modern Science. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637 The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London © 2009 by The University of Chicago All rights reserved. Published 2009 Printed in the United States of America 18 17 16 15 14 13 12 11 10 09 1 2 3 4 5 isbn-13: 978-0-226-06863-3 (cloth) isbn-10: 0-226-06863-3 (cloth) Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Bowler, Peter J. Science for all: the popularization of science in early twentieth- century Britain / Peter J. Bowler. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn-13: 978-0-226-06863-3 (cloth: alk. paper) isbn-10: 0-226-06863-3 (cloth: alk. paper) 1. Science news— Great Britain—History—20th century. 2. Communication in science—Great Britain—History—20th century. I. Title. q225.2.g7b69 2009 509.41'0904—dc22 2008055466 a The paper used in this publication meets the minimum re- quirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ansi z39.48-1992. -

{Replace with the Title of Your Dissertation}

Laboratory Literature: Science and Fiction in the Place of Production. A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Matthew James Hadley IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Adviser: Cesare Casarino October 2013 © Matthew Hadley 2013 i Acknowledgements I would like to thank the members of my dissertation committee for their patience, generosity, and care as teachers, mentors, and friends. To my advisor Cesare Casarino, whose ship I boarded shortly after coming to graduate school, I thank you for never making me walk the plank, even when I wanted to myself, and for showing me how the ship could carry me to the laboratory. There are a few people who deserve special thanks: Paige Sweet who read, edited, and commented on many incoherent and semi-incoherent versions of my chapters; Matt Stoddard who told me when I first asked for his help, and before he had done anything, that I should thank him profusely and gratuitously—I’ll just say that he was right, I should; And Laura Zebuhr, whose generosity and guidance with this dissertation, which carried me through to the end, taught me the meaning of true friendship. A warm thank you to my parents and my sisters for their unwavering love and support. Finally, to Chris Durler, whose help extends far beyond the practical and concrete, I offer my deepest gratitude. Graduate school changes a person, and I was lucky enough to share a home with someone who not only stood by my side from the very beginning, but also took on the more formidable challenge of growing with me. -

Literature Reviews

LITERATURE REVIEWS Readers are invited to submit reviews of current literature relating to origins. Mailing address: ORIGINS, Geoscience Research Institute, 11060 Campus St., Loma Linda, California 92350 USA. The Institute does not distribute the publications reviewed; please contact the publisher directly. EVIDENCE OR PREFERENCE AS A FOUNDATION FOR BELIEF? THE GREAT EVOLUTION MYSTERY. Gordon Rattray Taylor. 1983. NY: Harper & Row. 277 p. Reviewed by R. H. Brown, Geoscience Research Institute The Great Evolution Mystery is the last of fifteen books that distinguish Gordon Rattray Taylor as a brilliant writer and an original thinker. His broad scientific interests and his keen insight into issues of public concern, together with his literary skills, led to his selection as Chief Science Advisor for BBC television. Throughout this book Mr. Taylor expressed unwavering implicit confi- dence in naturalistic evolution as the correct view concerning the origin and development of life. However, the book contains the best collection of scientific evidence for creation that I have seen! One might suspect that the author was a closet creationist who posed as an evolutionist to get evolutionists to hear the evidence against their viewpoint. But as far as I am able to discern, Mr. Taylor was fully honest in his approach. The vast array of contradictory evidence he has presented is directed only against the Darwinian and neo- Darwinian explanations for evolution. Having demolished Darwinism he offers no replacement, other than the confidence that naturalistic evolution is the only correct general view, and that a satisfactory scientific foundation for it will be found eventually. He suggests that this foundation may include modified elements of Lamarckism and an innate property of matter and organisms for self-direction toward higher complexity and greater adaptability. -

Teaching Science of Origins

TEACHING SCIENCE OF ORIGINS TEACHING ORIGINS IN HIGH SCHOOL SCIENCE: RATIONALE AND CURRICULUM UNIT By JACK D. WESTERINK, B.Sc. A Project Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science (Teaching) McMaster University (c) Copyright by Jack D. Westerink, August 1989 MASTER OF SCIENCE (1989) McMASTER UNIVERSITY (Teaching) Hamilton, Ontario TITLE: Teaching Origins in High School Science AUTHOR: Jack D. Westerink, B.Sc. (University of Guelph) SUPERVISORS: Dr. D.A. Humphreys and Dr. S. Najm NUMBER OF PAGES: vi, 152 11 ABSTRACT Teaching science involves more than teaching facts, concepts, principles and theories. Science educators also have a . professional obligation to expose students to the values associated with those theories. People make decisions on value-laden, scientific questions 'from the perspective of their own world view. There should be room in our science curriculum to allow the student to form a personal position on the issues of our day after a fair presentation of the full range of alternatives. Even though the student may already have a firm position on the issue in question, the exercise will foster an understanding of the views of others and promote tolerance for those who differ. One of these issues is that of the origin of life. The objective of this project is to develop a rationale for teaching the full range of alternatives in the science classroom, and to provide a curriculum unit as a resource for teachers who want to give a balanced treatment of the issue in question. 111 Acknowledgements I wish to recognize the patient encouragement and counsel of Dr. -

Errors of the American National Academy of Sciences

n 1999, the National Academy of Sciences, USA, published a booklet called Science and Creationism: The National Academy of Science’s View. The aim of I this booklet was to respond to the creation/evolution debate by bringing together “the most important proofs” of evolution. The advertising campaign set in motion about this booklet was such that anyone seeing it might well imagine that it was full of evidence for the theory of evolution and had put a definitive end to all discussion of the validity of the theory. However, those who expected to find such evidence in it were sadly disappointed. The booklet makes not a single mention of the Cambrian Period, the real subject of debate as regards the theory of evolution and which can never be accounted for in terms of the theory. Nor does it discuss such matters as the origin of the cell or human consciousness. Despite having been disproved time and time again by scientific findings, evolutionists’ classic claims were simply repeated in a superficial manner, with no evidence offered to support them. With this new work, we wish to demonstrate how it is that the members of the National Academy of Sciences, USA, one of the world’s most eminent evolutionist institutions, came to be unable to see the most obvious truth and to distort the evidence and knowingly support a lie, because of their fanatical devotion to Darwinism and materialism. Those who read this book with an objective eye will once again see the truth in question—in other words the fact that the theory of evolution is being supported with a blind and totally dogmatic determination. -

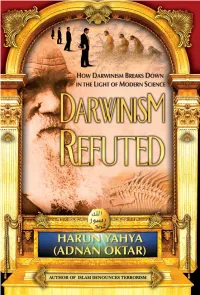

Darwinism Refuted

ABOUT THE AUTHOR Now writing under the pen-name of HARUN YAHYA, Adnan Oktar was born in Ankara in 1956. Having completed his primary and secondary education in Ankara, he studied fine arts at Istanbul's Mimar Sinan University and philosophy at Istanbul University. Since the 1980s, he has published many books on political, scientific, and faith- related issues. Harun Yahya is well-known as the author of important works disclosing the imposture of evolutionists, their invalid claims, and the dark liaisons between Darwinism and such bloody ideologies as fascism and communism. Harun Yahya's works, translated into 72 different languages, constitute a collection for a total of more than 55,000 pages with 40,000 illustrations. His pen-name is a composite of the names Harun (Aaron) and Yahya (John), in memory of the two esteemed Prophets who fought against their peoples' lack of faith. The Prophet's seal on his books' covers is symbolic and is linked to their contents. It represents the Qur'an (the Final Scripture) and Prophet Muhammad (saas), last of the prophets. Under the guidance of the Qur'an and the Sunnah (teachings of the Prophet [saas]), the author makes it his purpose to disprove each fundamental tenet of irreligious ideologies and to have the "last word," so as to completely silence the objections raised against religion. He uses the seal of the final Prophet (saas), who attained ultimate wisdom and moral perfection, as a sign of his intention to offer the last word. All of Harun Yahya's works share one single goal: to convey the Qur'an's message, encourage readers to consider basic faith- related issues such as Allah's existence and unity and the Hereafter; and to expose irreligious systems' feeble foundations and perverted ideologies.