Interview with VASCO ALBERT SMITH October 9,10, and 12, 2000 By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sequence 01 2 Page 1 of 25 Cheryl Cotton, Cameron Norman, Obdieah Robinson

Sequence 01_2 Page 1 of 25 Cheryl Cotton, Cameron Norman, Obdieah Robinson [0:00:00] Cheryl Cotton: Good morning. I’m Cheryl Fanion Cotton and I want to read something that I wrote. Several years ago I was up and couldn’t sleep and I went to my computer feeling a little blue. And I said “Cheryl, why don’t you write down some of the things you’ve done in life.” So that’s what I did. So these are called the “I Haves Of My Life.” I have attended church all of my life. My church is here in South Memphis. Saint Mary United Methodist Church. I have loved and respected all of God’s creations. I have dutifully accepted servanthood as a way of life. I earned my high school diploma from Booker T. Washington high school in 1968. I grew up in the Civil Rights Movement and marched with Dr. King. I have pictures in the Ernest Withers Museum downtown and I looked for it last night and I just could not find it. I earned my college degree from the University of Pittsburgh in 1973. [0:01:00] I attended the school of theology at Boston University in 1974, where Dr. King earned his PhD. I attended Pittsburgh Theological Seminary from 1975-1978 and I earned a Masters Divinity Degree from Memphis Theological Seminary in 2000. I was a student chaplain at the old St. Joseph Hospital in Memphis and my job was to go around and pray in the rooms of patients. But I always asked for permission. -

"I AM a 1968 Memphis Sanitation MAN!": Race, Masculinity, and The

LaborHistory, Vol. 41, No. 2, 2000 ªIAMA MAN!º: Race,Masculinity, and the 1968 MemphisSanitation Strike STEVEESTES* On March 28, 1968 Martin LutherKing, Jr. directeda march ofthousands of African-American protestersdown Beale Street,one of the major commercial thoroughfares in Memphis,Tennessee. King’ splane had landedlate that morning, and thecrowd was already onthe verge ofcon¯ ict with thepolice whenhe and other members ofthe Southern Christian LeadershipConference (SCLC) took their places at thehead of the march. The marchers weredemonstrating their supportfor 1300 striking sanitation workers,many ofwhom wore placards that proclaimed, ªIAm a Man.ºAs the throng advanceddown Beale Street,some of the younger strike support- ersripped theprotest signs off the the wooden sticks that they carried. Theseyoung men,none of whomwere sanitation workers,used the sticks to smash glass storefronts onboth sidesof the street. Looting ledto violent police retaliation. Troopers lobbed tear gas into groups ofprotesters and sprayed mace at demonstratorsunlucky enough tobe in range. High above thefray in City Hall, Mayor HenryLoeb sat in his of®ce, con®dent that thestrike wasillegal, andthat law andorder wouldbe maintained in Memphis.1 This march wasthe latest engagement in a®ght that had raged in Memphissince the daysof slaveryÐ acon¯ict over African-American freedomsand civil rights. In one sense,the ª IAm aManºslogan wornby thesanitation workersrepresented a demand for recognition oftheir dignity andhumanity. This demandcaught whiteMemphians bysurprise,because they had always prided themselvesas being ªprogressiveºon racial issues.Token integration had quietly replaced public segregation in Memphisby the mid-1960s, butin the1967 mayoral elections,segregationist candidateHenry Loeb rodea waveof white backlash against racial ªmoderationºinto of®ce. -

Scanned Using Book Scancenter 5131

An Unseen Li^ht Black Struggles for Freedom in Memphis, Tennessee Edited by Aram Goudsouzian and Charles W. McKinney Jr. UNIVERSITY PRESS OF KENTUCKY “Since I Was a Citizen, I Had the Bight to Attend the Library” The Key Role of the Public Library in the Civil Rights Movement in Memphis Steven A. Knowlton Memphian Jesse Turner, an African American, wanted his wife to be able to use the library. Throughout the winter of 1949 Allegra Turner was in mourning for a younger brother who had been killed in a railroad accident. Looking for a diversion, Jesse Turner suggested that a visit to the library might help Mrs. Turner “become engrossed in both fun and facts.Mr. Turner, an officer at the Tri-State Bank located just a few blocks from the Cossitt Library on Front Street, had used the Memphis Public Library’s main branch (named for its benefactor, Frederick Cos sitt) in the past. Crucially, he had never sat down or tried to borrow a book. Due to a quirk in the rules of segregation, Jesse Turner had been allowed to stand in the reference section while he looked up a few facts in a book. Had he attempted to use the fuU range of the hbrary’s facilities, he would have known better than to suggest that Mrs. Turner would be welcome at the Cossitt Library downtown. i Her travails that day encapsulate the eyeryday realities of African American life in segregated Memphis. Allegra Turner, who was familiar with the workings of libraries from her days as a student and instructor at Southern University and the University of Chicago, entered the library and made straight for the card catalog. -

Marching Across the Putative Black/White Race Line: a Convergence of Narratology, History, and Theory Carol L

Boston College Journal of Law & Social Justice Volume 33 | Issue 2 Article 2 May 2013 Marching Across the Putative Black/White Race Line: A Convergence of Narratology, History, and Theory Carol L. Zeiner St. Thomas University School of Law Follow this and additional works at: http://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/jlsj Part of the Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons, Legal History Commons, United States History Commons, and the Women's History Commons Recommended Citation Carol L. Zeiner, Marching Across the Putative Black/White Race Line: A Convergence of Narratology, History, and Theory, 33 B.C.J.L. & Soc. Just. 249 (2013), http://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/jlsj/vol33/iss2/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Boston College Journal of Law & Social Justice by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MARCHING ACROSS THE PUTATIVE BLACK/WHITE RACE LINE: A CONVERGENCE OF NARRATOLOGY, HISTORY, AND THEORY Carol L. Zeiner* Abstract: This Article introduces a category of women who, until now, have been omitted from the scholarly literature on the civil rights move- ment: northern white women who lived in the South and became active in the civil rights movement, while intending to continue to live in the South on a permanent basis following their activism. Prior to their activ- ism, these women may have been viewed with suspicion because they were “newcomers” and “outsiders.” Their activism earned them the pejorative label “civil rights supporter.” This Article presents the stories of two such women. -

Black Women's Music Database

By Stephanie Y. Evans & Stephanie Shonekan Black Women’s Music Database chronicles over 600 Africana singers, songwriters, composers, and musicians from around the world. The database was created by Dr. Stephanie Evans, a professor of Black women’s studies (intellectual history) and developed in collaboration with Dr. Stephanie Shonekon, a professor of Black studies and music (ethnomusicology). Together, with support from top music scholars, the Stephanies established this project to encourage interdisciplinary research, expand creative production, facilitate community building and, most importantly, to recognize and support Black women’s creative genius. This database will be useful for music scholars and ethnomusicologists, music historians, and contemporary performers, as well as general audiences and music therapists. Music heals. The purpose of the Black Women’s Music Database research collective is to amplify voices of singers, musicians, and scholars by encouraging public appreciation, study, practice, performance, and publication, that centers Black women’s experiences, knowledge, and perspectives. This project maps leading Black women artists in multiple genres of music, including gospel, blues, classical, jazz, R & B, soul, opera, theater, rock-n-roll, disco, hip hop, salsa, Afro- beat, bossa nova, soka, and more. Study of African American music is now well established. Beginning with publications like The Music of Black Americans by Eileen Southern (1971) and African American Music by Mellonee Burnim and Portia Maultsby (2006), -

Insidememphis

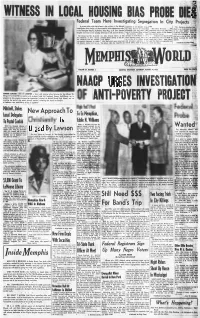

Federal Team Here Investigating Segregation In City Projects i A person who might have been a key witness in the federal apartment in the Memphis Hous that: “Mrs. McClaren requested that’I investigation Into charges of discrimination and segregation with ing setup because an expanding " Mrs. Marie McClaren .... has check to see if she could be housed in the Memphis Housing Authority died Aug. 2 at John Gdston automobile firm was taking ovtr made daily calls to this office (Dix in any other project, preferably Hospital and was buried Sunday afternoon in Mt Carmel Annex. land at the Ashland Street address. ie Homes) relative to her immed Lauderdale Court (all - whit«>,4t Mrs. .Cornelia Crenshaw, then iate need for housing. is her wish to remain In the htjft The witness was Mrs. Marie Ed ter, Mrs. Georgia Morris, at 205 manager of Dixie Homes, an all - “.. I informed her that we have pital area as she is under consta# dins McClaren of 337-C Decatur, Ashland before moving to the De Negro housing project, sent a let no vacancy nor notice of intent to clinical treatment for cancer itti Mrs. McClaren, who was undergo catur address. ter to Miss E. C. Wilson, leasing vacate on a three - room apart diabetes. ing constant treatment for cancer Mrs. McClaren's name came Into and occupancy supervisor at the ment for which her application was il ■ $ |s ■ and diabetes, resided with iiet sis- the picture when she requested an central office, June 9, explaining issued for rental. (Continued on Page IWt) ■ 1®i st sjg!FW ¡■Sì Z Al Memphi.„ fn i W 5, VOLUME 34, NUMBER 6 MEMPHIS, TENNESSEE, SATURDAY, AUGUST 14, 1965 4.- NAACP ES INVE 3 SUMMER SCHOOL'S LeMOYNE - Mrs. -

Potential for Tourism Development in Eastern Kentucky

Economics Potential for Tourism Development in Eastern Kentucky Prepared for Kentucky Chamber Foundation October 8, 2013 Table of Contents Strategic Recommendations ..................................................................................................................... 1 Possible Next Steps ...................................................................................................................................... 2 Conclusions ................................................................................................................................................... 4 Introduction ................................................................................................................................................. 5 National Tourism Trends ............................................................................................................................ 7 Trip Duration and Activities ........................................................................................................................... 8 Trip Spending ................................................................................................................................................ 9 Traveler Demographics and Preferences ................................................................................................... 10 Demographic Trends ................................................................................................................................... 11 Economic and Cultural Shifts ..................................................................................................................... -

Livability 2050 RTP Document

REGIONAL TRANSPORTATION PLAN UPDATE LIVABILITY REGIONAL TRANSPORTATION PLAN UPDATE connecting people & places 2050 This document is available in accessible formats when requested ten (10) calendar days in advance. This document was prepared and published by the Memphis Urban Area Metropolitan Planning Organization (MPO) and is prepared in cooperation with and financial assistance from the following public entities: the Federal Transit Administration (FTA), the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA), the Tennessee Department of Transportation (TDOT), the Mississippi Department of Transportation (MDOT), as well as the City of Memphis, Shelby County, Tennessee and DeSoto County, Mississippi. This financial assistance notwithstanding, the contents of this document do not necessarily reflect the official view or policies of the funding agencies. It is the policy of the Memphis MPO not to exclude, deny, or discriminate on the basis of race, color, national origin, ethnicity, immigration status, sex, gender, gender identity and expression, sexual orientation, age, religion, veteran status, familial or marital status, disability, medical or genetic condition, or any other characteristic protected under applicable federal or state law in its hiring or employment practices, or in its admission to, access to, or operations of its programs, services, or activities. All inquiries for Title VI and/or the Americans with Disabilities Act, contact Alvan-Bidal Sanchez at 901-636-7156 or [email protected]. Acknowledgments The Memphis Urban Area -

THE ROAD to CIVIL RIGHTS 2019 Teacher Ins[Tute

THE ROAD TO CIVIL RIGHTS 2019 Teacher InsItute Funded by The NATIONAL PARK SERVICE CIVIL RIGHTS FUND in partnership with The CITY OF MEMPHIS DIVISION OF HOUSING AND COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT CONTENTS Section 1 – Introducing MeMphis Heritage Trail Executive Summary 1 Overview of Memphis Heritage Trail 2 - 5 Cultural Heritage Tourism 6 Section 2 – The Teacher Institute The Memphis Heritage Trail Teachers Institute 8 Institute ScheDule 9 - 11 Memphis Heritage Trail Tour Locations 12 Select Sites within Memphis Heritage Trail 13 - 16 Section 3– Curriculum Development Primary Sources 18 Sample Lesson anD Format 19 - 21 Trekking the Trail 22 - 23 Civil Rights Timeline 24 - 27 Section 4 – Lessons: People Along the Trail 28 - 50 Section 5 – Lessons: Places Along the Trail 51 - 110 Section 6 – Lessons: Events Along the Trail 111 - 138 Appendix: Educators, Facilitators, Guest Panelists, Staff 139 - 143 SECTION 1 INTRODUCING MEMPHIS HERITAGE TRAIL EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Memphis Heritage Trail (MHT) launcheD in April 2018 During MLK50, a city-wiDe iniTave commemorang the 50th anniversary of the assassinaon of Dr. MarTn Luther King Jr. DevelopeD by the City of Memphis Division of Housing anD Community Development, MHT recognizes the significant contribuTons of African Americans. SituateD primarily in South City, the MHT is a 20-block area of historical anD cultural assets that reflect the nexus of African American culture, civil rights, entrepreneurship, intellectualism, anD musical innovaon. In adDiTon, MHT is DesigneD to strengthen the neighborhooD, revitalize physical structures anD spaces, sTmulate the economy, anD improve the quality of life. There are also two linkage neighborhoods – Soulsville anD Orange MounD, both preDominantly African American communiTes whose growth anD Development paralleleD South City. -

Memphis Voices: Oral Histories on Race Relations, Civil Rights, and Politics

Memphis Voices: Oral Histories on Race Relations, Civil Rights, and Politics By Elizabeth Gritter New Albany, Indiana: Elizabeth Gritter Publishing 2016 Copyright 2016 1 Table of Contents Introduction……………………………………………………………………………………..3 Chapter 1: The Civil Rights Struggle in Memphis in the 1950s………………………………21 Chapter 2: “The Ballot as the Voice of the People”: The Volunteer Ticket Campaign of 1959……………………………………………………………………………..67 Chapter 3: Direct-Action Efforts from 1960 to 1962………………………………………….105 Chapter 4: Formal Political Efforts from 1960 to 1963………………………………………..151 Chapter 5: Civil Rights Developments from 1962 to 1969……………………………………195 Conclusion……………………………………………………………………………………..245 Appendix: Brief Biographies of Interview Subjects…………………………………………..275 Selected Bibliography………………………………………………………………………….281 2 Introduction In 2015, the nation commemorated the fiftieth anniversary of the Voting Rights Act, which enabled the majority of eligible African Americans in the South to be able to vote and led to the rise of black elected officials in the region. Recent years also have seen the marking of the 50th anniversary of both the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which outlawed discrimination in public accommodations and employment, and Freedom Summer, when black and white college students journeyed to Mississippi to wage voting rights campaigns there. Yet, in Memphis, Tennessee, African Americans historically faced few barriers to voting. While black southerners elsewhere were killed and harassed for trying to exert their right to vote, black Memphians could vote and used that right as a tool to advance civil rights. Throughout the 1900s, they held the balance of power in elections, ran black candidates for political office, and engaged in voter registration campaigns. Black Memphians in 1964 elected the first black state legislator in Tennessee since the late nineteenth century. -

2019 Education Curriculum Guide

Tennessee Academic Standards 2019 EDUCATION CURRICULUM GUIDE MEMPHIS IN MAY INTERNATIONAL FESTIVAL Celebrates Memphis in 2019 For the fi rst time in its 43-year history, Memphis in May breaks with tradition to make the City of Memphis and Shelby County the year-long focus of its annual salute. Rather than another country, the 2019 Memphis in May Festival honors Memphis and Shelby County as both celebrate their bicentennials and the start of a new century for the city and county. Memphis has changed the world and will continue to change the world. We are a city of doers, dreamers, and believers. We create, we invent, we experiment; and this year, we invite the world to experience our beautiful home on the banks of the Mississippi River. The Bluff City…Home of the Blues, Soul, and Rock & Roll…a city where “Grit and Grind” are more than our team’s slogan, they’re who we are: determined, passionate, authentic, soulful, unstoppable. With more than a million residents in its metro area, the City of Memphis is a city of authenticity and diversity where everyone is welcomed. While some come because of its reputation as a world-renown incubator of talent grown from its rich musical legacy, Memphis draws many to its leading hospital and research systems, putting Memphis at the leading edge of medical and bioscience innovation. Situated nearly in the middle of the United States at the crossroads of major interstates, rail lines, the world’s second-busiest cargo airport, and the fourth-largest inland port on the Mississippi River, Memphis moves global commerce as the leader in transportation and logistics. -

Historic Bridges Historic Bridges 397 Survey Report for Historic Highway Bridges

6 HISTORIC BRIDGES HISTORIC BRIDGES 397 SURVEY REPORT FOR HISTORIC HIGHWAY BRIDGES HIGHWAY FOR HISTORIC REPORT SURVEY 1901-1920 PERIOD By the turn of the century, bridge design, as a profession, had sufficiently advanced that builders ceased erecting several of the less efficient truss designs such as the Bowstring, Double Intersection Pratt, or Baltimore Petit trusses. Also, the formation of the American Bridge Company in 1901 eliminated many small bridge companies that had been scrambling for recognition through unique truss designs or patented features. Thus, after the turn of the century, builders most frequently erected the Warren truss and Pratt derivatives (Pratt, Parker, Camelback). In addition, builders began to erect concrete arch bridges in Tennessee. During this period, counties chose to build the traditional closed spandrel design that visually evoked the form of the masonry arch. Floods in 1902 and 1903 that destroyed many bridges in the state resulted in counties going into debt to undertake several bridge replacement projects. One of the most concentrated bridge building periods at a county level occurred shortly before World War I as a result of legislation the state passed in 1915 that allowed counties to pass bond issues for road and bridge construction. Consequently, several counties initiated large road construction projects, for example, Anderson County (#87, 01-A0088-03.53) and Unicoi County (#89, 86-A0068- 00.89). This would be the last period that the county governments were the most dominant force in road and bridge construction. This change in leadership occurred due to the creation of the Tennessee State Highway Department in 1915 and the passage of the Federal Aid Highway Act of 1916.