06 Chapter 01.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Contributions of Lala Har Dayal As an Intellectual and Revolutionary

CONTRIBUTIONS OF LALA HAR DAYAL AS AN INTELLECTUAL AND REVOLUTIONARY ABSTRACT THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF ^ntiat ai pijtl000pi{g IN }^ ^ HISTORY By MATT GAOR CENTRE OF ADVANCED STUDY DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH (INDIA) 2007 ,,» '*^d<*'/. ' ABSTRACT India owes to Lala Har Dayal a great debt of gratitude. What he did intotality to his mother country is yet to be acknowledged properly. The paradox ridden Har Dayal - a moody idealist, intellectual, who felt an almost mystical empathy with the masses in India and America. He kept the National Independence flame burning not only in India but outside too. In 1905 he went to England for Academic pursuits. But after few years he had leave England for his revolutionary activities. He stayed in America and other European countries for 25 years and finally returned to England where he wrote three books. Har Dayal's stature was so great that its very difficult to put him under one mould. He was visionary who all through his life devoted to Boddhi sattava doctrine, rational interpretation of religions and sharing his erudite knowledge for the development of self culture. The proposed thesis seeks to examine the purpose of his returning to intellectual pursuits in England. Simultaneously the thesis also analyses the contemporary relevance of his works which had a common thread of humanism, rationalism and scientific temper. Relevance for his ideas is still alive as it was 50 years ago. He was true a patriotic who dreamed independence for his country. He was pioneer for developing science in laymen and scientific temper among youths. -

Nationalism in India Lesson

DC-1 SEM-2 Paper: Nationalism in India Lesson: Beginning of constitutionalism in India Lesson Developer: Anushka Singh Research scholar, Political Science, University of Delhi 1 Institute of Lifelog learning, University of Delhi Content: Introducing the chapter What is the idea of constitutionalism A brief history of the idea in the West and its introduction in the colony The early nationalists and Indian Councils Act of 1861 and 1892 More promises and fewer deliveries: Government of India Acts, 1909 and 1919 Post 1919 developments and India’s first attempt at constitution writing Government of India Act 1935 and the building blocks to a future constitution The road leading to the transfer of power The theory of constitutionalism at work Conclusion 2 Institute of Lifelog learning, University of Delhi Introduction: The idea of constitutionalism is part of the basic idea of liberalism based on the notion of individual’s right to liberty. Along with other liberal notions,constitutionalism also travelled to India through British colonialism. However, on the one hand, the ideology of liberalism guaranteed the liberal rightsbut one the other hand it denied the same basic right to the colony. The justification to why an advanced liberal nation like England must colonize the ‘not yet’ liberal nation like India was also found within the ideology of liberalism itself. The rationale was that British colonialism in India was like a ‘civilization mission’ to train the colony how to tread the path of liberty.1 However, soon the English educated Indian intellectual class realised the gap between the claim that British Rule made and the oppressive and exploitative reality of colonialism.Consequently,there started the movement towards autonomy and self-governance by Indians. -

Rrb Ntpc Top 100 Indian National Movement Questions

RRB NTPC TOP 100 INDIAN NATIONAL MOVEMENT QUESTIONS RRB NTPC TOP 100 INDIAN NATIONAL MOVEMENT QUESTIONS Stay Connected With SPNotifier EBooks for Bank Exams, SSC & Railways 2020 General Awareness EBooks Computer Awareness EBooks Monthly Current Affairs Capsules RRB NTPC TOP 100 INDIAN NATIONAL MOVEMENT QUESTIONS Click Here to Download the E Books for Several Exams Click here to check the topics related RRB NTPC RRB NTPC Roles and Responsibilities RRB NTPC ID Verification RRB NTPC Instructions RRB NTPC Exam Duration RRB NTPC EXSM PWD Instructions RRB NTPC Forms RRB NTPC FAQ Test Day RRB NTPC TOP 100 INDIAN NATIONAL MOVEMENT QUESTIONS 1. The Hindu Widows Remarriage act was Explanation: Annie Besant was the first woman enacted in which of the following year? President of Indian National Congress. She presided over the 1917 Calcutta session of the A. 1865 Indian National Congress. B. 1867 C. 1856 4. In which of the following movement, all the D. 1869 top leaders of the Congress were arrested by Answer: C the British Government? Explanation: The Hindu Widows' Remarriage Act A. Quit India Movement was enacted on 26 July 1856 that legalised the B. Khilafat Movement remarriage of Hindu widows in all jurisdictions of C. Civil Disobedience Movement D. Home Rule Agitation India under East India Company rule. Answer: A 2. Which movement was supported by both, The Indian National Army as well as The Royal Explanation: On 8 August 1942 at the All-India Indian Navy? Congress Committee session in Bombay, Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi launched the A. Khilafat movement 'Quit India' movement. The next day, Gandhi, B. -

Chandra Shekahr Azad

Chandra Shekahr Azad drishtiias.com/printpdf/chandra-shekahr-azad Why in News On 23rd July, India paid tribute to the freedom fighter Chandra Shekahr Azad on his birth anniversary. Key Points Birth: Azad was born on 23rd July 1906 in the Alirajpur district of Madhya Pradesh. Early Life: Chandra Shekhar, then a 15-year-old student, joined a Non-Cooperation Movement in December 1921. As a result, he was arrested. On being presented before a magistrate, he gave his name as "Azad" (The Free), his father's name as "Swatantrata" (Independence) and his residence as "Jail". Therefore, he came to be known as Chandra Shekhar Azad. 1/2 Contribution to Freedom Movement: Hindustan Republican Association: After the suspension of the non- cooperation movement in 1922 by Gandhi, Azad joined Hindustan Republican Association (HRA). HRA was a revolutionary organization of India established in 1924 in East Bengal by Sachindra Nath Sanyal, Narendra Mohan Sen and Pratul Ganguly as an offshoot of Anushilan Samiti. Members: Bhagat Singh, Chandra Shekhar Azad, Sukhdev, Ram Prasad Bismil, Roshan Singh, Ashfaqulla Khan, Rajendra Lahiri. Kakori Conspiracy: Most of the fund collection for revolutionary activities was done through robberies of government property. In line with the same, Kakori Train Robbery near Kakori, Lucknow was done in 1925 by HRA. The plan was executed by Chandrashekhar Azad, Ram Prasad Bismil, Ashfaqulla Khan, Rajendra Lahiri, and Manmathnath Gupta. Hindustan Socialist Republican Association: HRA was later reorganised as the Hindustan Socialist Republican Army (HSRA). It was established in 1928 at Feroz Shah Kotla in New Delhi by Chandrasekhar Azad, Ashfaqulla Khan, Bhagat Singh, Sukhdev Thapar and Jogesh Chandra Chatterjee. -

BA III, Paper VI, Anuradha Jaiswal Phase 1 1) Anusilan S

Revolutionaries In India (Indian National Movement) (Important Points) B.A III, Paper VI, Anuradha Jaiswal Phase 1 1) Anusilan Samiti • It was the first revolutionary organisation of Bengal. • Second Branch at Baroda. • Their leader was Rabindra Kumar Ghosh • Another important leader was P.Mitra who was the actual leader of the group. • In 1908, the samiti published a book called Bhawani Mandir. • In 1909 they published Vartaman Ranniti. • They also published a book called Mukti Kon Pathe (which way lie salvation) • Barindra Ghosh tried to explore a bomb in Maniktala in Calcutta. • Members – a) Gurudas Banerjee. b) B.C.Pal • Both of them believed in the cult of Durga. • Aurobindo Ghosh started Anushilan Samiti in Baroda. • He sent Jatindra Nath Banerjee to Calcutta and his association merged with Anusilan Samiti in Calcutta. 2) Prafull Chaki and Khudi Ram Bose • They tried to kill Kings Ford, Chief Presidency Magistrate, who was a judge at Muzaffarpur in Bihar but Mrs Kennedy and her daughter were killed instead in the blast. • Prafulla Chaki was arrested but he shot himself dead and Khudiram was hanged. This bomb blast occurred on 30TH April 1908. 3) Aurobindo Ghosh and Barindra Ghosh • They were arrested on May 2, 1908. • Barindra was sentenced for life imprisonment (Kalapani) and Aurobindo Ghosh was acquitted. • This conspiracy was called Alipore conspiracy. • The conspiracy was leaked by the authorities by Narendra Gosain who was killed by Kanhiya Lal Dutta and Satyen Bose within the jail compound. 4. Lala Hardayal, Ajit Singhand &Sufi Amba Prasad formed a group at Saharanpur in 1904. 5. -

Pan-Asianism: Rabindranath Tagore, Subhas Chandra Bose and Japan’S Imperial Quest

Karatoya: NBU J. Hist. Vol. 11 ISSN: 2229-4880 Pan-Asianism: Rabindranath Tagore, Subhas Chandra Bose and Japan’s Imperial Quest Mary L. Hanneman 1 Abstract Bengali intellectuals, nationalists and independence activists played a prominent role in the Indian independence movement; many shared connections with Japan. This article examines nationalism in the Indian independence movement through the lens of Bengali interaction with Japanese Pan-Asianism, focusing on the contrasting responses of Rabindranath Tagore and Subhas Chandra Bose to Japan’s Pan-Asianist claims . Key Words Japan; Pan-Asianism; Rabindranath Tagore; Subhas Chandra Bose; Imperialism; Nationalism; Bengali Intellectuals. Introduction As Japan pursued military expansion in East Asia in the 1930s and early 1940s, it developed a Pan-Asianist narrative to support its essentially nationalist ambitions in a quest to create an “Asia for the Asiatics,” and to unite all of Asia under “one roof”. Because it was backed by military aggression and brutal colonial policies, this Pan- Asianist narrative failed to win supporters in East Asia, and instead inspired anti- Japanese nationalists throughout China, Korea, Vietnam and other areas subject to Japanese military conquest. The Indian situation, for various reasons which we will explore, offered conditions quite different from those prevailing elsewhere in Asia writ large, and as a result, Japan and Indian enjoy closer and more cordial relationship during WWII and its preceding decades, which included links between Japanese nationalist thought and the Indian independence movement. 1 Phd, Modern East Asian History, University of Washington, Tacoma, Fulbright –Nehru Visiting Scholar February-May 2019, Department of History, University of North Bengal. -

Nationalism and Internationalism (Ca

Comparative Studies in Society and History 2012;54(1):65–92. 0010-4175/12 $15.00 # Society for the Comparative Study of Society and History 2012 doi:10.1017/S0010417511000594 Imagining Asia in India: Nationalism and Internationalism (ca. 1905–1940) CAROLIEN STOLTE Leiden University HARALD FISCHER-TINÉ Swiss Federal Institute of Technology, Zurich What is this new cult of Asianism, at whose shrine more and more incense is being offered by vast numbers of thinking Asiatics, far and near? And what has this gospel of Asianism, rightly understood and properly interpreted, to do with the merely political cry of ‘Asia for the Asiatics’? For true it is, clear to all who have eyes to see and ears to hear, that Asia is fast developing a new consciousness of her specific mission, her orig- inal contribution to Euro-America. ———Nripendra Chandra Banerji1 INTRODUCTION Asianisms, that is, discourses and ideologies claiming that Asia can be defined and understood as a homogenous space with shared and clearly defined charac- teristics, have become the subject of increased scholarly attention over the last two decades. The focal points of interest, however, are generally East Asian varieties of regionalism.2 That “the cult of Asianism” has played an important Acknowledgments: Parts of this article draw on a short essay published as: Harald Fischer-Tiné, “‘The Cult of Asianism’: Asiendiskurse in Indien zwischen Nationalismus und Internationalismus (ca. 1885–1955),” Comparativ 18, 6 (2008): 16–33. 1 From Asianism and other Essays (Calcutta: Arya Publishing House, 1930), 1. Banerji was Pro- fessor of English at Bangabasi College, Calcutta, and a friend of Chittaranjan Das, who propagated pan-Asianism in the Indian National Congress in the 1920s. -

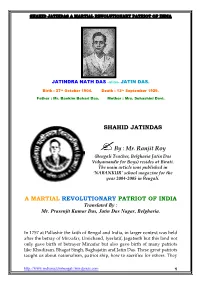

JATINDRA NATH DAS -Alias- JATIN DAS

JATINDRA NATH DAS -alias- JATIN DAS. Birth : 27 th October 1904. Death : 13 th September 1929. Father : Mr. Bankim Behari Das. Mother : Mrs. Suhashini Devi. SHAHID JATINDAS ?By : Mr. Ranjit Roy (Bengali Teacher, Belgharia Jatin Das Vidyamandir for Boys) resides at Birati. The main article was published in ‘NABANKUR’ school magazine for the year 2004-2005 in Bengali. A MARTIAL REVOLUTIONARY PATRIOT OF INDIA Translated By : Mr. Prasenjit Kumar Das, Jatin Das Nagar, Belgharia. In 1757 at Pallashir the faith of Bengal and India, in larger context was held after the betray of Mirzafar, Umichand, Iyerlatif, Jagatseth but this land not only gave birth of betrayer Mirzafar but also gave birth of many patriots like Khudiram, Bhagat Singh, Baghajatin and Jatin Das. These great patriots taught us about nationalism, patriot ship, how to sacrifice for others. They http://www.indianactsinbengali.wordpress.com 1 have tried their best to uphold the head of a unified, independent and united nation. Let us discuss about one of them, Jatin Das and his great sacrifice towards the nation. on 27 th October 1904 Jatin Das (alias Jatindra Nath Das) came to free the nation from the bondage of the British Rulers. He born at his Mother’s house at Sikdar Bagan. He was the first child of father Bankim Behari Das and mother Suhashini Devi. After birth the newborn did not cried for some time then the child cried loudly, it seems that the little one was busy in enchanting the speeches of motherland but when he saw that his motherland is crying for her bondage the little one cant stop crying. -

Ideology and Practice of National Movement

UNIVERSITY OF CALICUT SCHOOL OF DISTANCE EDUCATION SECOND SEMESTER M.A. HISTORY PAPER- IV IDEOLOGY AND PRACTICE OF THE NATIONAL MOVEMENT (2008 Admission onwards) Prepared by Dr.N.PADMANABHAN Reader P.G.Department of History C.A.S.College, Madayi P.O.Payangadi-RS-670358 Dt.Kannur-Kerala. CHAPTERS CONTENTS PAGES 1 NATURE OF THE COLONIAL STATE 02-38 11 COLONIAL IDEOLOGY 39- 188 111 TOWARDS A THEORY OF NATIONALISM 189-205 1V NATIONALIST RESISTANCE 206-371 V INDEPENDENCE AND PARTITION 371-386 1 CHAPTER-1 NATURE OF THE COLONIAL STATE THE COLONIAL STATE AS A MODERN REGIME OF POWER Does it serve any useful analytical purpose to make a distinction between the colonial state and the forms of the modern state? Or should we regard the colonial state as simply another specific form in which the modern state has generalized itself across the globe? If the latter is the case, then of course the specifically colonial form of the emergence of the institutions of the modern state would be of only incidental, or at best episodic, interest; it would not be a necessary part of the larger, and more important, historical narrative of modernity.The idea that colonialism was only incidental to the history of the development of the modern institutions and technologies of power in the countries of Asia and Africa is now very much with us. In some ways, this is not surprising, because we now tend to think of the period of colonialism as something we have managed to put behind us, whereas the progress of modernity is a project in which we are all, albeit with varying degrees of enthusiasm, still deeply implicated. -

Ram Prasad Bismil - Poems

Classic Poetry Series Ram Prasad Bismil - poems - Publication Date: 2013 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive Ram Prasad Bismil(11 June 1897 - 19 December 1927) Ram Prasad Bismil (Hindi: ??? ?????? '???????') was an Indian revolutionary who participated in Mainpuri Conspiracy of 1918, and the Kakori conspiracy of 1925, both against British Empire. As well as being a freedom fighter, he was also a patriotic poet. Ram, Agyat and Bismil were known as his pen names which he used in Urdu and Hindi poetry. But, he became popular with the last name "Bismil" only. He was associated with Arya Samaj where he got inspiration from Satyarth Prakash, a book written by Swami Dayanand Saraswati. He also had a confidential connection with Lala Har Dayal through his guru Swami Somdev, who was a renowned preacher of Arya Samaj. Bismil was one of the founder members of the revolutionary organisation Hindustan Republican Association. Bhagat Singh praised him as a great poet- writer of Urdu and Hindi, who had also translated the books Catherine from English and Bolshevikon Ki Kartoot from Bengali. Several inspiring patriotic verses are attributed to him. The famous poem "Sarfaroshi ki Tamanna" is also popularly attributed to him, although some progressive writers have remarked that 'Bismil' Azimabadi actually wrote the poem and Ram Prasad Bismil immortalized it. <b> Early life Ram Prasad Bismil was born at Shahjahanpur, a historical city of Uttar Pradesh (U.P.) in a religious Hindu family of Murlidhar and Moolmati. <b> Grandfather's migration </b> His grandfather Narayan Lal was migrated from his ancestral village Barbai and settled at a very distant place Shahjahanpur in U.P. -

The Career of Muhammad Barkatullah (1864-1927): from Intellectual to Anticolonial Revolutionary

THE CAREER OF MUHAMMAD BARKATULLAH (1864-1927): FROM INTELLECTUAL TO ANTICOLONIAL REVOLUTIONARY Samee Nasim Siddiqui A thesis submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Arts in the Department of History in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences. Chapel Hill 2017 Approved by: Cemil Aydin Susan B. Pennybacker Iqbal Sevea © 2017 Samee Nasim Siddiqui ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Samee Nasim Siddiqui: The Career of Muhammad Barkatullah (1864-1927): From Intellectual to Anticolonial Revolutionary (Under the direction of Cemil Aydin) This thesis analyzes the transition of Muhammad Barkatullah, a Muslim-Indian living under British colonial rule, from intellectual to anti-British revolutionary. The thesis assumes that this transition was not inevitable and seeks to explain when, why, and how Barkatullah became radicalized and turned to violent, revolutionary means in order to achieve independence from British rule, and away from demanding justice and equality within an imperial framework. To do this, the focus of the thesis is on the early period of his career leading up to the beginning of WWI. It examines his movements, intellectual production, and connections with various networks in the context of of major global events in order to illuminate his journey to revolutionary anti-colonialism. iii To my parents iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I have had the good fortune of receiving incredible mentorship and support throughout the process of writing and researching this thesis. I would like to begin by thanking my advisor, Cemil Aydin, who proposed the idea of working on this remarkable figure. -

Lajpat Rai in USA 1914 -1919: Life and Work of a Political Exile

Harish K. Puri Lajpat Rai in USA 1914 -1919: Life and Work of a Political Exile he five year long stay of Lajpat Rai in America (including a six month sojourn in T Japan) was a period of an unanticipated exile contrived by conditions created by the World War. When he sailed from London for New York in November 1914, it was proposed to be a six month trip to collect material for a book on America. But he was not allowed to return to India until the end of 1919. The nature of his life and work in USA was shaped as much by the constraints and challenges in the American situation as by his priorities and the state of his mind. A contextual approach to the study of his work for the national cause of India in USA may be more appropriate for the present exploration. Before we go into the American context of his life and experience, it may be necessary, however, to have an insight into the state of his mind before he went there. The evidence available suggests that when he left India in April 1914 to catch up with the Congress Delegation in England, it appeared to be an escape ‘in panic’. He had lived under grave anxiety when three of the young men closely connected with him were involved as the accused in Lahore-Delhi conspiracy case. Balraj was the son of his close friend Lala Hans Raj. Balmukund, brother of Bhai Parmanand, had lived with Lajpat Rai and worked as his valuable assistant in his social work and aid for the depressed classes.