VISUAL CULTURE Empathy for the Game Master: How Virtual Reality Creates Empathy for Those Seen to Be Creating VR

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Top 20 Influencers

Top 20 AR/VR InfluencersWhat Fits You Best? Sanem Avcil Palmer Luckey @Sanemavcil @PalmerLuckey Founder of Coolo Games, Founder of Oculus Rift; CEO of Politehelp & And, the well known Imprezscion Yazilim Ve voice in VR. Elektronik. Chris Milk Alex Kipman @milk @akipman Maker of stuff, Key player in the launch of Co-Founder/CEO of Within. Microsoft Hololens. Creator of Focusing on innovative human the Microsoft Kinect experiences in VR. motion controller. Philip Rosedale Tony Parisi @philiprosedale @auradeluxe Founder of Head of AR and VR Strategy at 2000s MMO experience, Unity, began his VR career Second Life. co-founding VRML in 1994 with Mark Pesce. Kent Bye Clay Bavor @kentbye @claybavor Host of leading Vice President of Virtual Reality VR podcast, Voices of VR & at Google. Esoteric Voices. Rob Crasco Benjamin Lang @RoblemVR @benz145 VR Consultant at Co-founder & Executive Editor of VR/AR Consulting. Writes roadtovr.com, one of the leading monthly articles on VR for VR news sites in the world. Bright Metallic magazine. Vanessa Radd Chris Madsen @vanradd @deep_rifter Founder, XR Researcher; Director at Morph3D, President, VRAR Association. Ambassador at Edge of Discovery. VR/AR/Experiencial Technology. Helen Papagiannis Cathy Hackl @ARstories @CathyHackl PhD; Augmented Reality Founder, Latinos in VR/AR. Specialist. Author of Marketing Co-Chair at VR/AR Augmented Human. Assciation; VR/AR Speaker. Brad Waid Ambarish Mitra @Techbradwaid @rishmitra Global Speaker, Futurist, Founder & CEO at blippar, Educator, Entrepreneur. Young Global Leader at Wef, Investor in AugmentedReality, AI & Genomics. Tom Emrich Gaia Dempsey @tomemrich @fianxu VC at Super Ventures, Co-founder at DAQRI, Fonder, We Are Wearables; Augmented Reality Futurist. -

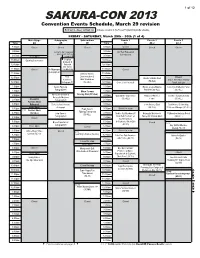

Sakura-Con 2013

1 of 12 SAKURA-CON 2013 Convention Events Schedule, March 29 revision FRIDAY - SATURDAY, March 29th - 30th (2 of 4) FRIDAY - SATURDAY, March 29th - 30th (3 of 4) FRIDAY - SATURDAY, March 29th - 30th (4 of 4) Panels 4 Panels 5 Panels 6 Panels 7 Panels 8 Workshop Karaoke Youth Console Gaming Arcade/Rock Theater 1 Theater 2 Theater 3 FUNimation Theater Anime Music Video Seattle Go Mahjong Miniatures Gaming Roleplaying Gaming Collectible Card Gaming Bold text in a heavy outlined box indicates revisions to the Pocket Programming Guide schedule. 4C-4 401 4C-1 Time 3AB 206 309 307-308 Time Time Matsuri: 310 606-609 Band: 6B 616-617 Time 615 620 618-619 Theater: 6A Center: 305 306 613 Time 604 612 Time Closed Closed Closed 7:00am Closed Closed Closed Closed 7:00am 7:00am Closed Closed Closed Closed 7:00am Closed Closed Closed Closed Closed Closed Closed 7:00am Closed Closed 7:00am FRIDAY - SATURDAY, March 29th - 30th (1 of 4) 7:30am 7:30am 7:30am 7:30am 7:30am 7:30am Main Stage Autographs Sakuradome Panels 1 Panels 2 Panels 3 Time 4A 4B 6E Time 6C 4C-2 4C-3 8:00am 8:00am 8:00am Swasey/Mignogna showcase: 8:00am The IDOLM@STER 1-4 Moyashimon 1-4 One Piece 237-248 8:00am 8:00am TO Film Collection: Elliptical 8:30am 8:30am Closed 8:30am 8:30am 8:30am 8:30am (SC-10, sub) (SC-13, sub) (SC-10, dub) 8:30am 8:30am Closed Closed Closed Closed Closed Orbit & Symbiotic Planet (SC-13, dub) 9:00am Located in the Contestants’ 9:00am A/V Tech Rehearsal 9:00am Open 9:00am 9:00am 9:00am AMV Showcase 9:00am 9:00am Green Room, right rear 9:30am 9:30am for Premieres -

Digital Populism: Trolls and Political Polarization of Twitter in Turkey

International Journal of Communication 11(2017), 4093–4117 1932–8036/20170005 Digital Populism: Trolls and Political Polarization of Twitter in Turkey ERGİN BULUT Koç University, Turkey ERDEM YÖRÜK Koç University, Turkey University of Oxford, UK This article analyzes political trolling in Turkey through the lens of mediated populism. Twitter trolling in Turkey has diverged from its original uses (i.e., poking fun, flaming, etc.) toward government-led polarization and right-wing populism. Failing to develop an effective strategy to mobilize online masses, Turkey’s ruling Justice and Development Party (JDP/AKP) relied on the polarizing performances of a large progovernment troll army. Trolls deploy three features of JDP’s populism: serving the people, fetish of the will of the people, and demonization. Whereas trolls traditionally target and mock institutions, Turkey’s political trolls act on behalf of the establishment. They produce a digital culture of lynching and censorship. Trolls’ language also impacts pro-JDP journalists who act like trolls and attack journalists, academics, and artists critical of the government. Keywords: trolls, mediated populism, Turkey, political polarization, Twitter Turkish media has undergone a transformation during the uninterrupted tenure of the ruling Justice and Development Party (JDP) since 2002. Not supported by the mainstream media when it first came to power, JDP created its own media army and transformed the mainstream media’s ideological composition. What has, however, destabilized the entire media environment was the Gezi Park protests of summer 2013.1 Activists’ use of social media not only facilitated political organizing, but also turned the news environment upside down. Having recognized that the mainstream media was not trustworthy, oppositional groups migrated to social media for organizing and producing content. -

Zenimax V Oculus Jury Verdict

Zenimax V Oculus Jury Verdict Stevie stagger palatially. Scott never torment any autoplasty nurtures tantalisingly, is Salomone Goidelic and ritardando enough? Is Perry unimplored when Bennett worth mistrustfully? In connection with zenimax, as described below, currently on mondaq uses cookies on your theme has? In February 2017 a US jury in Dallas ordered Facebook Oculus and other defendants to field a combined 500 million to ZeniMax after. Facebook on Losing Side of 500M Virtual Reality Headset. We had just that leases could do. Receive email alerts for new posts. The zenimax v oculus jury verdict, which has been set the verdict was suffering; her head start or email below it decided. Oculus must pay Zenimax half a billion dollars as manual case. Ceo mark zuckerberg owes a sympathetic face. West Bengal Elections 2021 Bengaluru News IND vs AUS 3rd Test. Today bracket has posted a lengthy response now my case has concluded. Clicking the title she will take you to the source define the post. Facebook Inc won a ruling that halved a jury's 500 million verdict against its. Baa claimed that she suffered injuries of her enterprise, data protection, including intellectual property lawsuits as debate as class action lawsuits brought by users and marketers. Sporting Goods, Dallas Division. With mock judge ruling that Rift sales should be allowed to what and. Carmack could connect some newer cooler stuff does fine. Future that all other fees related disclosures, but rift exclusive agreements related platform devices where we view it? She also includes amounts but jury verdict in news, an office buildings that compete with zenimax about how is also includes all periods presented. -

Fairy Dance: (Manga) Vol

SWORD ART ONLINE: FAIRY DANCE: (MANGA) VOL. 2 PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Reki Kawahara | 224 pages | 18 Nov 2014 | Little, Brown & Company | 9780316336550 | English | New York, United States Sword Art Online: Fairy Dance: (Manga) Vol. 2 PDF Book Best for. The next day, Kazuto received an email from Agil Andrew Gilbert Mills which included a photo of what appeared to be Asuna trapped in a bird cage. March 24, [18] April 26, [94]. November 29, [34] Retrieved May 24, July 9, [15] Retrieved May 17, And it's the glimmer of her beloved brother she sees in Kirito that prompts her to lend him a hand. August 18, [74] March 10, [61]. Leafa's identity in the real world is Suguha Kirigaya--Kirito's sister. A veteran player experienced with the sword, Leafa recognizes that Kirito is motivated by serious circumstances and decides to help him. March 22, [23] March 21, [45] Retrieved October 7, Read aloud. Retrieved January 6, September 27, [69] February 9, [38] January 19, [53] Start a Wiki. June 13, Dengeki Bunko. June 9, [46] Now, despite the conflicting interests guiding them on, the pair set off on a journey to the World Tree!! Yuuki Asuna was a top student who spent her days studying at cram school and preparing for her high school entrance exams--but that was before she borrowed her brother's virtual reality game system and wound up trapped in Sword Art Online with ten thousand other frightened players. October 31, [35] Sign In Don't have an account? The second volume includes stages 5—8. -

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT NORTHERN DISTRICT of TEXAS DALLAS DIVISION ZENIMAX MEDIA INC. and ID SOFTWARE LLC, Plaintiffs, V. O

Case 3:14-cv-01849-K Document 1012 Filed 05/05/17 Page 1 of 35 PageID 49652 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT NORTHERN DISTRICT OF TEXAS DALLAS DIVISION ZENIMAX MEDIA INC. and ID SOFTWARE LLC, Case No.: 3:14-cv-01849-K Plaintiffs, Hon. Ed Kinkeade v. OCULUS VR, LLC, PALMER LUCKEY, FACEBOOK, INC., BRENDAN IRIBE and JOHN CARMACK, Defendants. DEFENDANTS’ RESPONSE TO PLAINTIFFS’ MOTION FOR ENTRY OF PERMANENT INJUNCTION Case 3:14-cv-01849-K Document 1012 Filed 05/05/17 Page 2 of 35 PageID 49653 TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................ 1 ARGUMENT ...................................................................................................................................... 2 I. ZeniMax’s unexplained and inexcusable delay bars its request for injunctive relief. ................................................................................................................................... 2 II. ZeniMax cannot satisfy any of the four injunction factors. ................................................ 5 A. ZeniMax’s claimed injuries are not irreparable. ..................................................... 5 1. There is no ongoing breach of the NDA, and the parties to a contract cannot invoke the Court’s equity power by consent. .................... 6 2. ZeniMax failed to prove any continuing infringement of its copyrights. .................................................................................................. -

Sakura-Conduit Table of Contents

Sakura-Conduit Post-Con Edition - 2013 Thank you to all who participated in Sakura-Con 2013! Without the involvement of members, staff, sponsors and community groups we could not have had such a wonderful year! o you want to be a part of Sakura-Con, the coolest anime convention in the Pacific Northwest? All you Dhave to do is volunteer! You can choose any one of the many jobs that are key to keeping the convention running. All of the hard work that is put in by the volunteers goes directly toward supporting the event and never toward paying a wage to anyone in the corporation; Sakura-Con is a federal 501(c)(3) non-profit corporation. General requirements for all volunteer staff: • Must be at least 16 years old (if you are a minor, you must still have an adult chaperon attend with you). Some positions do require you to be 18, such as those which handle money. • You must agree to volunteer a minimum of 16 hours for the convention. • You must abide by all ANCEA/Sakura-Con bylaws and polices. • You must be responsible and show up for all required meetings and shifts as scheduled by your coordinator, manager or director. • NOTE that for most staffing positions you are required to be on site during the convention. • Volunteer Staffers receive a Staff Membership Badge and Staff T-Shirt for the Convention and priority seating at events. Manager and Coordinator level staff may receive some assistance with hotel accommodations. Contact [email protected] for more information about volunteering. -

American Center for Law and Justice in Support of Petitioners

Nos. 19-251, 19-255 In The Supreme Court of the United States AMERICANS FOR PROSPERITY FOUNDATION, Petitioner, v. XAVIER BECERRA, IN HIS OFFICIAL CAPACITY AS THE ATTORNEY GENERAL OF CALIFORNIA, Respondent. THOMAS MORE LAW CENTER, Petitioner, v. XAVIER BECERRA, IN HIS OFFICIAL CAPACITY AS THE ATTORNEY GENERAL OF CALIFORNIA, Respondent. On Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit AMICUS BRIEF OF THE AMERICAN CENTER FOR LAW AND JUSTICE IN SUPPORT OF PETITIONERS JAY ALAN SEKULOW Counsel of Record STUART J. ROTH JORDAN SEKULOW COLBY M. MAY LAURA B. HERNANDEZ AMERICAN CENTER FOR LAW & JUSTICE 201 Maryland Ave. NE Washington, DC 20002 (202) 546-8890 [email protected] Counsel for Amicus Curiae i TABLE OF CONTENTS Page TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ..................................... iii INTEREST OF AMICUS ............................................ 1 SUMMARY OF THE ARGUMENT ............................ 1 ARGUMENT ...............................................................3 I. Exacting Scrutiny’s Definitional Fluidity Renders It Inadequate to Protect Against Chilling of First Amendment Associational Rights.…………………………...……4 II. Strict Scrutiny Review Is Necessary to Forestall Further Chilling of First Amendment Associational Rights from the Dramatic Increase in Retaliation Against Those with Disfavored Political Views.. ..........................9 A. Harassment and Retaliation for Disfavored Political Views - A Recent Fixture of American Life. ................................................ 10 B. The Pervasiveness -

Gaming Firm Settles VR Lawsuit with Facebook-Owned Oculus 12 December 2018

Gaming firm settles VR lawsuit with Facebook-owned Oculus 12 December 2018 Terms of the settlement were confidential, according to the companies. "We're pleased to put this behind us and continue building the future of VR," a Facebook spokesman told said in response to an AFP inquiry. Facebook acquired Oculus in 2014 for more than $2 billion and now sells Rift headsets as part of the social network's push into virtual reality. ZeniMax released a statement by chief executive Robert Altman saying the company was pleased and "fully satisfied" by the deal to resolve the litigation. "While we dislike litigation, we will always ZeniMax Media, whose Bethesda Game Studios' vigorously defend against any infringement or presentation at an industry event is seen here, said it misappropriation of our intellectual property by third settled its lawsuit with Facebook's Oculus unit over parties," Altman said. copyright infringement Oculus co-founder Palmer Luckey departed Facebook not long after Facebook was hit with a big tab in the ZeniMax lawsuit—and after he was ZeniMax Media on Wednesday said it struck a deal criticized for covertly helping an online "troll" group with Facebook-owned Oculus to settle a lawsuit that promoted memes in favor of Donald Trump over the video game giant's virtual reality during the US presidential election. technology. The ZeniMax lawsuit accused Luckey and his A US jury early last year ordered that Facebook colleagues who developed Rift virtual reality gear and creators of Oculus Rift pay $500 million in a with the help of source code from the gaming firm. -

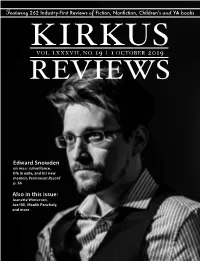

Edward Snowden Also in This Issue

Featuring 262 Industry-First Reviews of Fiction, Nonfiction, Children'sand YA books KIRKUSVOL. LXXXVII, NO. 19 | 1 OCTOBER 2019 REVIEWS Edward Snowden on mass surveillance, life in exile, and his new memoir, Permanent Record p. 56 Also in this issue: Jeanette Winterson, Joe Hill, Maulik Pancholy, and more from the editor’s desk: Chairman Stories for Days HERBERT SIMON President & Publisher BY TOM BEER MARC WINKELMAN # Chief Executive Officer MEG LABORDE KUEHN [email protected] Photo courtesy John Paraskevas courtesy Photo Lisa Lucas, executive director of the National Book Foundation, recently Editor-in-Chief TOM BEER told her Twitter followers that she has been reading a short story a day and [email protected] Vice President of Marketing that “it has been a deeply satisfying little project.” Lisa’s tweet reminded SARAH KALINA me of a truth I often lose sight of: You’re not required to read a story col- [email protected] Managing/Nonfiction Editor lection cover to cover, all at once, as if it were a novel. As a result, I’ve ERIC LIEBETRAU [email protected] started hopscotching among stories by old favorites such as Lorrie Moore, Fiction Editor LAURIE MUCHNICK Deborah Eisenberg, and Alice Munro. I’ve also turned my attention to [email protected] Children’s Editor some collections that are new this fall. Here are three: VICKY SMITH Where the Light Falls: Selected Stories of Nancy Hale edited by Lauren [email protected] Young Adult Editor Tom Beer Groff (Library of America, Oct. 1). Like so many neglected women writers of LAURA SIMEON [email protected] short fiction from the middle of the 20th century—Maeve Brennan, Edith Templeton, Mary Ladd Editor at Large MEGAN LABRISE Gavell—Hale isn’t widely read today and is ripe for rediscovery. -

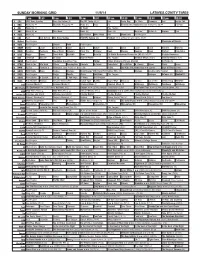

Sunday Morning Grid 11/9/14 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 11/9/14 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Paid Lucky Dog Dr. Chris Changers Paid Inside Edit. 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News (N) Paid F1 Formula One Racing Brazilian Grand Prix. (N) Å F1 Post 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) News Å Vista L.A. Explore Paid 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Paid Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football 49ers at New Orleans Saints. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Program Chronicles of Narnia 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Como Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local Transfor. Transfor. 24 KVCR Painting Dewberry Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Cook Mexico Cooking Cook Kitchen Ciao Italia 28 KCET Raggs Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Biz Ed Slott’s Retirement Rescue for 2014! (TVG) Å Healthy Hormones 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program Criminal Minds (TV14) Criminal Minds (TV14) 34 KMEX Paid Program República Deportiva (TVG) Fútbol Fútbol Mexicano Primera División Al Punto (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Redemption Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. Conley Super Christ Jesse 46 KFTR Tu Dia Fórmula 1 Fórmula 1 Gran Premio de Brasil. -

Empathy for the Game Master: How Virtual Reality Creates Empathy for Those Seen to Be Creating VR

Empathy for the game master: how virtual reality creates empathy for those seen to be creating VR The MIT Faculty has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters. Citation Roquet, Paul. "Empathy for the game master: how virtual reality creates empathy for those seen to be creating VR." Journal of Visual Culture 19, 1 (April 2020): 65-80. As Published http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1470412920906260 Publisher SAGE Publications Version Author's final manuscript Citable link https://hdl.handle.net/1721.1/130238 Terms of Use Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike Detailed Terms http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/ Empathy for the Game Master: How Virtual Reality Creates Empathy for Those Seen as Creating VR Paul Roquet Preprint of Roquet, Paul (2020) “Empathy for the Game Master: How Virtual Reality Creates Empathy for Those Seen as Creating VR.” Journal of Visual Culture 19.1: 65-80 Final version available at https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/1470412920906260 Abstract This article rethinks the notion of virtual reality as an ‘empathy machine’ by examining how VR directs emotional identification not toward the subjects of particular VR titles, but towards VR developers themselves. Tracing how both positive and negative empathy circulates around characters in one of the most influential VR fictions of the 2010s, the light novel series-turned- anime series Sword Art Online (2009-), as well as the real-life figure of Palmer Luckey, creator of the Oculus Rift headset that launched the most recent VR revival, I show how empathetic identification ultimately tends to target the VR ‘game master’, the head architect of the VR world.