An Inquiry Into the Internationally Minded Curriculum

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![App. 1 APPENDIX a [DO NOT PUBLISH] in the UNITED STATES](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3534/app-1-appendix-a-do-not-publish-in-the-united-states-2613534.webp)

App. 1 APPENDIX a [DO NOT PUBLISH] in the UNITED STATES

App. 1 APPENDIX A [DO NOT PUBLISH] IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE ELEVENTH CIRCUIT ----------------------------------------------------------------------- No. 17-10259 Non-Argument Calendar ----------------------------------------------------------------------- D.C. Docket No. 1:16-cv-21140-KMM LEIGH ANNE MARSHALL, Plaintiff-Appellant, versus ROYAL CARIBBEAN CRUISES, LTD., Defendant-Appellee. ----------------------------------------------------------------------- Appeal from the United States District Court for the Southern District of Florida ----------------------------------------------------------------------- (November 30, 2017) Before JORDAN, JULIE CARNES, and JILL PRYOR, Circuit Judges. PER CURIAM: Leigh Marshall brought this maritime personal injury action against Royal Caribbean Cruises for injuries she allegedly sustained while on board the App. 2 Enchantment of the Seas on March 5, 2016. It had rained off and on throughout that day, and it was un- disputed that Ms. Marshall and her traveling compan- ions were aware of the rain and the wetness of the external surfaces of the ship. Near midnight, as Ms. Marshall reached the bottom of a flight of external stairs she was descending, she slipped on a puddle on the deck at the bottom of the stairs and twisted her ankle. Following discovery, the district court granted summary judgment in favor of Royal Caribbean, con- cluding that any alleged danger presented by the wet external deck was open and obvious, and that Royal Caribbean had no duty to specifically warn Ms. Mar- shall of the wetness. The court also found that Ms. Marshall had failed to present sufficient evidence that Royal Caribbean had actual or constructive notice of any dangerous condition regarding the wet floor or the staircase. Ms. Marshall now appeals. After reviewing the record and the parties’ briefs, and for the reasons outlined in the district court’s thor- ough and well-reasoned discussion of the duty owed by Royal Caribbean to Ms. -

Metallimusiikki Musiikkiyhtye & Musiikin Esittã¤J㤠Lista

Metallimusiikki Musiikkiyhtye & Musiikin esittäjä Lista Masterpiece https://fi.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/masterpiece-22967514/albums Mikko Härkin https://fi.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/mikko-h%C3%A4rkin-1079969/albums Blaze Bayley https://fi.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/blaze-bayley-1756800/albums Chainsaw https://fi.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/chainsaw-5395589/albums Brats https://fi.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/brats-4958082/albums Piet Sielck https://fi.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/piet-sielck-69837/albums Machine Men https://fi.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/machine-men-498636/albums Dan Nelson https://fi.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/dan-nelson-3298514/albums Gotham Road https://fi.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/gotham-road-3773639/albums Oliver/Dawson Saxon https://fi.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/oliver%2Fdawson-saxon-1092373/albums Stonegard https://fi.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/stonegard-12003345/albums Symbols https://fi.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/symbols-3507540/albums T & N https://fi.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/t-%26-n-2382920/albums Masterstroke https://fi.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/masterstroke-5479786/albums Kobus! https://fi.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/kobus%21-3643369/albums Saber Tiger https://fi.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/saber-tiger-11543506/albums Motör Militia https://fi.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/mot%C3%B6r-militia-1718843/albums Tribuzy https://fi.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/tribuzy-3998670/albums JonnyX and the Groadies https://fi.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/jonnyx-and-the-groadies-6275706/albums -

RECORD SHOP Gesamtkatalog Gültig Bis 30.06.2021 Record Shop Holger Schneider Flurstr

RECORD SHOP GESamtkatalOG gültig bis 30.06.2021 Record Shop Holger Schneider Flurstr. 7, 66989 Höheinöd, Germany Tel.: (0049) 06333-993214 Fax: (0049) 06333-993215 @Mail: [email protected] Homepage: www.recordshop-online.de Gruppe / Titel Artikelbeschreibung B.-Nr.Preis Gruppe / Titel Artikelbeschreibung B.-Nr. Preis 10 CC STIFF UPPER LIP LIVEDVD 2001 M-/M 2085 9,99 € GREATEST HITS 1972 - 1978CD M-/M 90675 4,99 € AC/DC - BON SCOTT 12 STONES THE YEARS BEFORE AC/DCDVD M/M 1870 4,99 € 12 STONESCD M-/M 97005 6,99 € AC/DC - VARIOUS ARTITS POTTERS FIELDCD M/M 97004 6,99 € BACK IN BLACKCD A TRIBUTE TO AC/DC M/M 85519 5,99 € 18 SUMMERS THE MANY FACES OFCD 3 CD BOX Lim. Edition im Digipack !!! EX-/EX/EX/EX 96776 6,99 € VIRGIN MARYCD EX-/M- 93108 4,99 € ACCEPT 23RD GRADE OF EVIL ACCEPTCD D/2005/Steamhammer M/M 99871 19,99 € WHAT WILL REMAIN WHEN WE ARE GCD M-/M 98249 9,99 € ACCEPTLP Spain/79/Victoria Lady Lou.... M/M 20437 14,99 € BALLS TO THE WALLCD D/2002/BMG 12 TRACKS 98714 6,99 € 24 K BEST OFCD M/M- 77627 4,99 € BULLETPROOFCD EX-/M 82303 4,99 € BEST OFLP D/83/Braun EX/EX 20345 7,99 € PURECD EX-/M- 72083 4,99 € BLOOD OF NATIONSCD M-/M 95090 7,99 € 3 DOORS DOWN HUNGRY YEARSCD DIGITAL REMIX M-/M- 50773 6,99 € THE BETTER LIFECD M/M 84233 2,99 € LIVE IN JAPANLP D/85RCA EX/EX -Co- 10371 6,99 € 30.000 Kollegen LIVE IN JAPANLP D/85RCA M-/EX 20482 7,99 € Allein auf weiter flurLP M/M 20841 5,99 € LIVE IN JAPANLP D/85RCA M-/M 20431 9,99 € 36 CRYZYFISTS METAL MASTERSCD EX-/M- 63277 4,99 € PREDATORCD EX-/M 81397 9,99 € COLLISIONS AND CASTWAYSCD M/M 89364 2,99 € RUSSIAN ROULETTECD Remastered Edition mit 2 Bonus Livetracks OVP 87910 6,99 € 38 SPECIAL THE ACCEPT COLLECTIONCD BOX 3 CD SET EU/2010/UNIVERSAL EX/EX-/EX/EX+ 91760 6,99 € BONE AGAINST STEELCD EX-/M- 94026 6,99 € RESOLUTIONCD EX/M 94022 4,99 € ACCEPT / VA A TRIBUTE TO ACCEPT ICD Lim. -

06/12/2020 This Catalogue Cancels And

www.endofsilence.net This catalogue cancels and replaces any previous catalogue 06/12/2020 Questo catalogo annulla e sostituisce i cataloghi in data precedente LP (New, Used & Rarities) CD 1917 (Argentina) - Vision - CD, Album, RE, VG/VG+ € 4,90 217 - Atheist Agnostic Rationalist - CD, Album, Sealed M/M € 7,90 3 Inches Of Blood - Advance And Vanquish - CD, Album, Great copy, like new! NM/NM € 7,90 36 Crazyfists - Bitterness The Star - CD, Album, Sealed M/M € 6,90 95-C - Stuck In The past - CD, NM/VG+ € 4,90 A.N.I.M.A.L. - Animal 6 - CD, Album, Like new NM/NM € 7,90 Abominant - Onward To Annihilation - CD, Album, Dig, Sealed M/M € 9,90 ABORYM - Generator - CD - € 9,90 ABORYM - WITH NO HUMAN INTERVENTION - CD - 2003 - G /VG - USED € 5,90 Aborym - Psychogrotesque - CD, Album, Ltd, Dig, M/M € 9,90 Abrasive - Awakening of lust - CD € 6,90 Absolute Defiance - Systematic terror decimation - CD € 4,90 ABYSSUS - Into the Abyss - CD - € 9,90 AC/DC - Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap - CD € 9,90 AC/DC - Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap - CD € 11,90 AC/DC - Let Ther Be Rock - CD € 7,90 AC/DC - Rock or Bust - CD Digi Sealed € 11,90 AC/DC - Stiff upper lip - CD € 7,90 ACCEPT - DEATH ROW - CD - US PRESS 1995 - VG/VG - Used € 9,90 Accept - Hungry years - CD. Used € 6,90 ACCEPT - Metal heart - CD - Remastered Sealed € 9,90 Acheron - Kult Des Hasses - CD, Album, Sli, Sealed M/M € 7,90 ACROSTICHON - Engraved in Black - CD - Memento Mori Rec € 9,90 Action Swingers - More Fast Numbers - CD, EP, NM/VG+ € 4,90 www.endofsilence.net WhatsApp/Telegram/SMS: +39 3518979595 www.endofsilence.net [email protected] Pag. -

"Dimebag" Darrell Abbott

0306815249-Crain.qxd:Layout 1 3/16/09 10:58 AM Page i BLACK TOOTH GRIN THE HIGH LIFE, GOOD TIMES, AND TRAGIC END OF “DIMEBAG” DARRELL ABBOTT Zac Crain Da Capo Press A Member of the Perseus Books Group 0306815249-Crain.qxd:Layout 1 3/16/09 10:58 AM Page ii Copyright © 2009 by Zac Crain All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. Printed in the United States of America. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Crain, Zac. Black tooth grin : the high life, good times, and tragic end of 'Dimebag' Darrell Abbott / Zac Crain. p. cm. Includes discography. ISBN 978-0-306-81524-9 (alk. paper) 1. Abbott, Darrell. 2. Guitarists—United States—Biography 3. Rock musicians—Biography. I. Title. ML419.A04C73 2009 787.87'166092—dc22 [B] 2008040662 First Da Capo Press edition 2009 Published by Da Capo Press A Member of the Perseus Books Group www.dacapopress.com Da Capo Press books are available at special discounts for bulk purchases in the U.S. by corporations, institutions, and other organizations. For more information, please contact the Special Markets Department at the Perseus Books Group, 2300 Chestnut Street, Suite 200, Philadelphia PA 19103, or call (800) 810-4145, extension 5000, or e-mail [email protected]. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 0306815249-Crain.qxd:Layout 1 3/16/09 10:58 AM Page iii TRACK LISTING Introduction: -

Vol. 6. Nos. 3 & 4

archipelago An International Journal of Literature, the Arts, and Opinion www.archipelago.org Vol. 6, Nos. 3 & 4 Winter 2003 Journalism: ROBERT FISK The Keys of Palestine, from PITY THE NATION A New Series: Living with Guns MARY-SHERMAN WILLIS, The Fight for Kansas MARILYN A. JOHNSON, Why They Shot Us A Garland of Poets CAROLYN HEMBREE, Until Anne’s Shadow's on the Curtain PATRICIA CONNOLLY, Five Poems CHRISTIAN McEWEN, A Winter Alphabet KATHRYN RANTALA, The Finnish Orchestra Essay: ROBERT CASTLE From Desperation to Salvation: On Eugen Rosenstock-Huessy Letter from Bhutan: RORY McEWEN to Ron Padgett The Curator’s Eye: VERNA POSEVER CURTIS Three Photographers: Halverson, Klett, Burtynsky Endnotes: KATHERINE McNAMARA A Year in Washington Recommended Reading: George Garrett on Madison Jones Letters to the Editor: The Election Printed from our Download (pdf) Edition archipelago An International Journal of Literature, the Arts, and Opinion www.archipelago.org Vol. 6, Nos. 3 & 4 Winter 2003 The Keys of Palestine Robert Fisk 14 Living With Guns Introduction 46 The Fight for Kansas / Mary-Sherman Willis 47 Why They Shot Us / Marilyn A. Johnson 69 A Garland of Poets Carolyn Hembree 72 Patricia Connolly 73 Christian McEwen 78 Kathryn Rantala 80 From Desperation to Salvation: On Eugen Rosenstock-Huessy Robert Castle 86 Letter from Bhutan Rory McEwen 95 The Curator’s Eye: on Halverson, Klett, Burtynsky Verna Posever Curtis 103 Endnotes: A Year in Washington Katherine McNamara 109 Recommended Reading: George Garrett on Madison Jones 128 Letters to the Editor: On the Election 6 Masthead 3 Contributors 3 Support Archipelago 135 ARCHIPELAGO 2 Vol. -

![Исполнитель Альбом Год Стиль Лейбл Формат Примечание CD Wroth Emitter Tumulus Winter Wood [3Rd Press, Gold CD] 2004 Folk Progressive Wroth Emitter CD W.E](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1316/cd-wroth-emitter-tumulus-winter-wood-3rd-press-gold-cd-2004-folk-progressive-wroth-emitter-cd-w-e-8571316.webp)

Исполнитель Альбом Год Стиль Лейбл Формат Примечание CD Wroth Emitter Tumulus Winter Wood [3Rd Press, Gold CD] 2004 Folk Progressive Wroth Emitter CD W.E

Исполнитель Альбом Год Стиль Лейбл Формат Примечание CD Wroth Emitter Tumulus Winter Wood [3rd press, gold CD] 2004 folk progressive Wroth Emitter CD W.E. 003 Deimos Never Be Awaken 2004 death doom progressive Wroth Emitter CD W.E. 004 Eternal Sin Christ's False Torments 2005 true black Wroth Emitter CD W.E. 006 Tumulus Sredokresie 2005 folk progressive Wroth Emitter CD W.E. 007; promo version also available Stonehenge Victims Gallery 2005 doom death Wroth Emitter CD W.E. 008 Патриарх Тёмный мир людей 2006 black Wroth Emitter CD W.E. 009 Protector Welcome To Fire 2006 cult thrash Wroth Emitter CD W.E. 010 Tumulus Live Balkan Path 2006 folk progressive Wroth Emitter CD W.E. 011 Majdanek Waltz О происхождении Мира 2006 dark folk / ambient Wroth Emitter CD W.E. 012 Todesstoß Spiegel Der Urängste / Sehnsucht 2007 cryptic black Wroth Emitter CD W.E. 013 Al'virius Beyond The Human Nation 2007 sympho thrash Wroth Emitter CD W.E. 014 Karsten Hamre / Vlad Jecan Enter Inside [split] 2007 dark ambient Wroth Emitter CD W.E. 015 Aglaomorpha Perception 2007 doom death avantgarde Wroth Emitter CD W.E. 016 Kogai Hagakure 2007 melodic death progressive Wroth Emitter CD W.E. 017 Tumulus Кочевонов Пляс 2008 folk progressive Wroth Emitter MCD W.E. 018; promo version also available Tsaraas Шепот зарытых сердец 2008 dark ambient Wroth Emitter CD W.E. 019 Venuspuls Herzschlag Des Endzeit-Architekten 2008 dark ambient / electro Wroth Emitter CD W.E. 020 Mystica Dreams In Real Forms 2008 progressive metal Wroth Emitter CD W.E. -

Digital There Has Been Some Really Cool Things in with Laptops

S NT TE Out Of The Blue ON 2. INDEPENDENCE FEST 12. OZZFEST P.O. Box 388 C Local festival has Ozzfest caliber. Off stage with DevilDriver, Delaware OH 43015 O 4. OMFG ChthoniC and The Showdown. www.myspace.com/ Area fest brings diverse original bands. 15. VANS WARPED TOUR O 7. WOODSHOCK Behind the scenes interviews out_of_the_blue646 Account of one of Ohio’s largest events. and Cleveland’s washout. T 9. INDI$TINCT FREESTYLE 17. WARPED EXPERIENCE Editor-in-Chief Area blader’s alternative sport. On the road with Tom. Neil Shumate B 10. UNDERGROUND SOUNDS 18. MILWAUKEE SUMMERFEST SOTU let rip the dogs of Gwar. Fans Trip proves worthwhile, with or without meeting Panic!. Copy Editor pleased with piss and blood showers. John Shumate 19. LOGANPALOOZA 32. SCENE OF THE CRIME Alien Robot God on Prelude. Writers A chat with founder Logan Maddy. 33. AIDEN Allyson Below 20. BATTLE FOR THE COVER WiL addresses the changes made to Tiffany Cook Fans voted and we talk to Bonk, CC Manded Volume Dealer, Headchange. redefine new release Conviction. Josh Davis 26. 34. GOING OVERSEAS Jim Hutter LITTLE BROTHERS Jim Hutter reflects on the former venue. New album interviews with blokes Matt Monnette 27. in Underworld and Enter Shikari. Erin Nye INTERVIEWS Otep, Bury Your Dead, The Warriors, 37. SHE WANTS REVENGE Kristen Oldham The Junior Varsity, The Red Chord. With a new release on deck, Adam-12 Neil Shumate 31. REVIEWS takes us through the band’s progression. The Lowdown features Mystic Syntax, 38. BETWEEN THE BURIED AND ME Contributing Writers Heartbreak Orchestra and more. -

22/04/2020 This Catalogue Cancels And

www.endofsilence.net This catalogue cancels and replaces any previous catalogue 22/04/2020 Questo catalogo annulla e sostituisce i cataloghi in data precedente CD (New, Used & Rarities)/LP/10"/7" CD 1917 (Argentina) - Vision - CD € 3,90 3 Inches Of Blood - Advance And Vanquish CD € 6,90 95-C - Stuck In The past - CD - Near Mint (NM or M-)/Very Good Plus (VG+) € 4,90 A.N.I.M.A.L. - Animal 6 - CD - NM/NM € 6,90 ABHORER - Cenotaphical Tri-Memoriumyths (Digipack CD) - CD € 9,90 ABOMINANT - Onward To Annihilation (Digipack CD) - CD € 9,90 Aborted - Engineering the dead - CD - FIRST FRENCH PRESS 2001 - VG - USED € 8,90 ABORTED - Slaughter & Apparatus: A Methodical Overture - CD - NM/NM € 7,90 ABORYM - Generator - CD - € 9,90 ABORYM - Psychogrotesque - CD - € 9,90 ABORYM - WITH NO HUMAN INTERVENTION - CD - 2003 - G /VG - USED € 5,30 Abrasive - Awakening of lust - CD € 5,50 Absolute Defiance - Systematic terror decimation - CD € 3,90 Abysmal Grief - Feretri - CD € 9,90 ABYSSUS - Into the Abyss - CD - € 9,90 AC/DC - Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap - CD € 9,90 AC/DC - Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap - Digi € 11,90 AC/DC - Let There Be Rock - CD - NM/VG+ Used € 7,90 AC/DC - Stiff upper lip - CD € 7,90 ACCEPT - DEATH ROW - CD - US PRESS 1995 - VG/VG - Used € 8,90 Accept - Hungry years - CD. Used € 6,20 ACCEPT - Metal heart - CD - € 9,90 Acheron - Kult Des Hasses - CD - € 7,90 ACROSTICHON - Engraved in Black - CD - € 9,90 Action Swingers - More Fast Numbers - CD. Used € 4,40 ADVERSOR - The End Of Mankind - CD € 7,90 www.endofsilence.net WhatsApp/Telegram/SMS: +39 3518979595 www.endofsilence.net [email protected] Pag. -

Rue Morgue 023 (2001)

! ' i 9 /T1 I / ITiiilitiiiniiiii- In >- t/bH THE UNIVERSE OF STEPHEN KING ‘ PLUS r FANTASIA 2001 THREE EROM EUECI PSYCHOBILLY BLOOD PARR AND MUCH, MUCH MORE! MARRS MEDIA L\C, September/Octobcr 2001j www.ru laBHfiniinsijtwflra, 6 "" 22571 "70633 6 Syirr Re^ St+er B 1 |x|CmeJ ‘Seriesl IwWW.L.lVl^O)EADCX^LLS.CClM /fe 9 idc^im cfiS'g'^... Used to cut a path ofdestruction through medieval Europe, comes The Sword of Dracula. TTiis beautiful sword measures 34 inches in overall length and sports a 27-inch blade of high carbon steel and a brass pommel. Each sword comes complete with a unique "coffin-shaped" wall plaque, with an attached candle shelf, so this dramatic sword can be displayed in the proper fashion. Also unthin this unholy collection, is Vlad Dracula’s unique walk- ing cane. This masterpiece features Vlad’s family crest, his father's infamous "Dragon," as its handle. Stretching a full 38rinches in length, this dark replica can also be purchased as a sword cane. With a push of a button, located just under the Dragon, you can release the thin, deadly blade of this deceptive cane. This piece also comes with a wall-mount- ing display plaque. Finally, the third piece ofthe Dracula Collection is Quincey’s Rhino-headed Bowie Knife. Measuring 17" in overall length, this massive Bowie Knife sports a 420 y stainless steel blade. After being dragged into the safety of Castle - >4^11 Dracula, Vlad's precious Mina rips ^ '• Quincey's Bowie from the chest of the dying vampire prince, and delivers the fatal blow by removing his head, ending his tormented life as Nosferatu. -

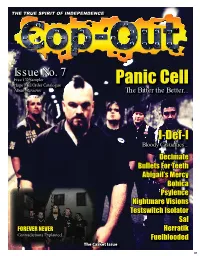

Cop out Magazine 07 – Web Version

TTHEHE TRUETRUE SPIRITSPIRIT OFOF INDEPENDENCEINDEPENDENCE IIssuessue No.No. 7 FFreeree CCDD SSamplerampler PPanicanic CCellell HHugeuge MMailail OOrderrder CCatalogueatalogue AAlbumlbum RReviewseviews TThehe BBitteritter tthehe BBetter...etter... II-Def-I-Def-I BBloodyloody CCasualties...asualties... DDecimateecimate BBulletsullets ForFor TeethTeeth AAbigail’sbigail’s MMercyercy BBohicaohica PPsylencesylence NNightmareightmare VVisionsisions TTestswitchestswitch IIsolatorsolator SSalal FFOREVEROREVER NNEVEREVER HHerratikerratik CContradictionsontradictions EExplained...xplained... FFuelbloodeduelblooded TThehe CCasketasket IssueIssue 01 02 CCOP-OUTOP-OUT #7#7 IIss bboughtought ttoo yyouou withwith thhee hhelpelp aandnd aassistences of the following people. Welcome To Cop-Out 07 sistence of the following people. HHelloello andand welcomewelcome toto anotheranother instalmentinstalment ofof Cop-Out,Cop-Out, thethe underfunded,underfunded, badlybadly writtenwritten andand cclobberedlobbered togethertogether catazinecatazine fromfrom thosethose jokersjokers atat CoproCopro Towers.Towers. SomeSome ofof youyou willwill bebe sur-sur- EEDITORDITOR JJoseose GGrifriffi n pprisedrised toto fi nnallyally havehave anotheranother oneone ofof thesethese fallfall onon youryour doordoor mat,mat, somesome ofof you,you, willwill bebe wonder-wonder- [email protected]@coproreords.co.uk iingng jjustust wwhathat tthehe hellhell thisthis is,is, butbut hopefullyhopefully allall ofof you,you, oror atat thethe veryvery leastleast mostmost ofof you,you, -

Napster, Labels Face Off in Court, on Capitol Hill

MUST HEAR Napster, Labels Face Off In Court, On Capitol Hill Both sides in the digital music copyright oppose new technology, but sees Napster as debate recently squared off in Washington, •hindering the dissemination of music online. D.C. before the Senate Judiciary Committee, "How can we embrace anew format and sell our chaired by Sen. Orrin Hatch (R-Utah). music for afair price when someone, with afew Witnesses included Napster CEO Hank lines of code and no investment costs, creative Barry, MP3.com CEO Michael Robertson, and input or marketing expenses, simply gives it Lars Ulrich, the drummer for Metallica, who has away?" Ulrich asked the committee. been one of Napster's most outspoken critics. The Metallica drummer specifically advo- Ulrich emphasized that Metallica does not cated legislation to keep (Continued on page 10) LUCKY STARS Judge Won't Dismiss Suit Against Sony Cuts 500 Promoters, Agents Staffers Worldwide A federal judge lias ruled that an antitrust and civil Sony Music Entel Liniment has rights suit filed by black concert promoters against ahost of announced that it will lay off near- major booking agencies and concert promotion companies ly 500 employees at its offices can go forward. around the world, representing 3.7 Judge Robert Patterson Jr. of the United States District percent of the company's 13,500 Court for the Southern District of New York refused to dismiss workers. The layoffs will cut across the case, Rowe Entertainment, Inc. et al. vs. The William all labels and divisions. Morris Agency, Inc, et al. The suit was filed by five black The company said that it was promoters who allege that they were prevented from book- "redirecting its resources on a ing concerts by booking agencies and (Continued on page 10) wo rldwide (Continued on page 10) ZURDOK Chris Knox On The 'Beat' With 1`31 THIS New Solo Outing `J.