Vol. 6. Nos. 3 & 4

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

4.Employment Education Hebrew Arnona Culture and Leisure

Did you know? Jerusalem has... STARTUPS OVER OPERATING IN THE CITY OVER SITES AND 500 SYNAGOGUES 1200 39 MUSEUMS ALTITUDE OF 630M CULTURAL INSTITUTIONS COMMUNITY 51 AND ARTS CENTERS 27 MANAGERS ( ) Aliyah2Jerusalem ( ) Aliyah2Jerusalem JERUSALEM IS ISRAEL’S STUDENTS LARGEST CITY 126,000 DUNAM Graphic design by OVER 40,000 STUDYING IN THE CITY 50,000 VOLUNTEERS Illustration by www.rinatgilboa.com • Learning centers are available throughout the city at the local Provide assistance for olim to help facilitate a smooth absorption facilities. The centers offer enrichment and study and successful integration into Jerusalem. programs for school age children. • Jerusalem offers a large selection of public and private schools Pre - Aliyah Services 2 within a broad religious spectrum. Also available are a broad range of learning methods offered by specialized schools. Assistance in registration for municipal educational frameworks. Special in Jerusalem! Assistance in finding residence, and organizing community needs. • Tuition subsidies for Olim who come to study in higher education and 16 Community Absorption Coordinators fit certain criteria. Work as a part of the community administrations throughout the • Jerusalem is home to more than 30 institutions of higher education city; these coordinators offer services in educational, cultural, sports, that are recognized by the Student Authority of the Ministry of administrative and social needs for Olim at the various community Immigration & Absorption. Among these schools is Hebrew University – centers. -

Retail Prices in a City*

Retail Prices in a City Alon Eizenberg Saul Lach The Hebrew University and CEPR The Hebrew University and CEPR Merav Yiftach Israel Central Bureau of Statistics July 2017 Abstract We study grocery price differentials across neighborhoods in a large metropolitan area (the city of Jerusalem, Israel). Prices in commercial areas are persistently lower than in residential neighborhoods. We also observe substantial price variation within residential neighborhoods: retailers that operate in peripheral, non-a uent neighborhoods charge some of the highest prices in the city. Using CPI data on prices and neighborhood-level credit card data on expenditure patterns, we estimate a model in which households choose where to shop and how many units of a composite good to purchase. The data and the estimates are consistent with very strong spatial segmentation. Combined with a pricing equation, the demand estimates are used to simulate interventions aimed at reducing the cost of grocery shopping. We calculate the impact on the prices charged in each neighborhood and on the expected price paid by its residents - a weighted average of the prices paid at each destination, with the weights being the probabilities of shopping at each destination. Focusing on prices alone provides an incomplete picture and may even be misleading because shopping patterns change considerably. Specifically, we find that interventions that make the commercial areas more attractive and accessible yield only minor price reductions, yet expected prices decrease in a pronounced fashion. The benefits are particularly strong for residents of the peripheral, non-a uent neighborhoods. We thank Eyal Meharian and Irit Mishali for their invaluable help with collecting the price data and with the provision of the geographic (distance) data. -

Itinerary Is Subject to Change. •

Itinerary is Subject to Change. • Welcome to Israel! Upon arrival, transfer to the Carlton Hotel in Tel Aviv. At 7:30 pm, enjoy a special welcome dinner at Blue Sky restaurant by Chef Meir Adoni, located on the rooftop of the hotel. After a warm welcome from the mission chairs, hear an overview of the upcoming days and learn more about JNF’s Women for Israel group. Tel Aviv Overnight, Carlton Hotel, Tel Aviv • Early this morning, everyone is invited to join optional yoga class on the beach. Following breakfast, participate in a special workshop that will provide an Yoga on the Beach introduction to the mission and the women on the trip. Depart the hotel for the Alexander Muss High School in Israel (AMHSI), the only non- denominational, pluralistic, accredited academic program in Israel for English speaking North American High School students. Following a tour, meet school administrators several students, who will share their experiences from the program. Join them at the new AMHSI Ben-Dor Radio Station for a special activity. AMHSI students Afterward, enjoy lunch at a local restaurant in Tel Aviv. Hear from top Israeli reporter, investigative journalist and anchorwoman Ilana Dayan, who will provide an update on the current social, political and cultural issues shaping Israel. This afternoon, enjoy a walking tour through Old Jaffa, an 8000-year-old port city. Walk through the winding alleyways, stop at the ancient ruins and explore the restored artist's quarter. Continue to the Ilana Goor Museum, an ever-changing, living exhibition that houses over 500 works of art by Ilana Goor and other celebrated artists. -

Xerox University Microfilms 300 North Zeeb Road Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106 75-6523 HEMBREE, Charles William, 1939- NARRATIVE TECHNIQUE in the FICTION of EUDORA WELIY

INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again - beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

General Assembly Distr.: General 3 October 2001 English Original: English/French

United Nations A/56/428 General Assembly Distr.: General 3 October 2001 English Original: English/French Fifty-sixth session Agenda item 88 Report of the Special Committee to Investigate Israeli Practices Affecting the Human Rights of the Palestinian People and Other Arabs of the Occupied Territories Report of the Special Committee to Investigate Israeli Practices Affecting the Human Rights of the Palestinian People and Other Arabs of the Occupied Territories Note by the Secretary-General* The General Assembly, at its fifty-fifth session, adopted resolution 55/130 on the work of the Special Committee to Investigate Israeli Practices Affecting the Human Rights of the Palestinian People and Other Arabs of the Occupied Territories, in which, among other matters, it requested the Special Committee: (a) Pending complete termination of the Israeli occupation, to continue to investigate Israeli policies and practices in the Occupied Palestinian Territory, including Jerusalem, and other Arab territories occupied by Israel since 1967, especially Israeli lack of compliance with the provisions of the Geneva Convention relative to the Protection of Civilian Persons in Time of War, of 12 August 1949, and to consult, as appropriate, with the International Committee of the Red Cross according to its regulations in order to ensure that the welfare and human rights of the peoples of the occupied territories are safeguarded and to report to the Secretary- General as soon as possible and whenever the need arises thereafter; (b) To submit regularly to the Secretary-General periodic reports on the current situation in the Occupied Palestinian Territory, including Jerusalem; (c) To continue to investigate the treatment of prisoners in the Occupied Palestinian Territory, including Jerusalem, and other Arab territories occupied by Israel since 1967. -

Greater Jerusalem” Has Jerusalem (Including the 1967 Rehavia Occupied and Annexed East Jerusalem) As Its Centre

4 B?63 B?466 ! np ! 4 B?43 m D"D" np Migron Beituniya B?457 Modi'in Bei!r Im'in Beit Sira IsraelRei'ut-proclaimed “GKharbrathae al Miasbah ter JerusaBeitl 'Uer al Famuqa ” D" Kochav Ya'akov West 'Ein as Sultan Mitzpe Danny Maccabim D" Kochav Ya'akov np Ma'ale Mikhmas A System of Settler-Colonialism and Apartheid Deir Quruntul Kochav Ya'akov East ! Kafr 'Aqab Kh. Bwerah Mikhmas ! Beit Horon Duyuk at Tahta B?443 'Ein ad D" Rafat Jericho 'Ajanjul ya At Tira np ya ! Beit Liq Qalandi Kochav Ya'akov South ! Lebanon Neve Erez ¥ ! Qalandiya Giv'at Ze'ev D" a i r Jaba' y 60 Beit Duqqu Al Judeira 60 B? a S Beit Nuba D" B? e Atarot Ind. Zone S Ar Ram Ma'ale Hagit Bir Nabala Geva Binyamin n Al Jib a Beit Nuba Beit 'Anan e ! Giv'on Hahadasha n a r Mevo Horon r Beit Ijza e t B?4 i 3 Dahiyat al Bareed np 6 Jaber d Aqbat e Neve Ya'akov 4 M Yalu B?2 Nitaf 4 !< ! ! Kharayib Umm al Lahim Qatanna Hizma Al Qubeiba ! An Nabi Samwil Ein Prat Biddu el Almon Har Shmu !< Beit Hanina al Balad Kfar Adummim ! Beit Hanina D" 436 Vered Jericho Nataf B? 20 B? gat Ze'ev D" Dayr! Ayyub Pis A 4 1 Tra Beit Surik B?37 !< in Beit Tuul dar ! Har A JLR Beit Iksa Mizpe Jericho !< kfar Adummim !< 21 Ma'ale HaHamisha B? 'Anata !< !< Jordan Shu'fat !< !< A1 Train Ramat Shlomo np Ramot Allon D" Shu'fat !< !< Neve Ilan E1 !< Egypt Abu Ghosh !< B?1 French Hill Mishor Adumim ! B?1 Beit Naqquba !< !< !< ! Beit Nekofa Mevaseret Zion Ramat Eshkol 1 Israeli Police HQ Mesilat Zion B? Al 'Isawiya Lifta a Qulunyia ! Ma'alot Dafna Sho'eva ! !< Motza Sheikh Jarrah !< Motza Illit Mishor Adummim Ind. -

The Monthly Report on the Israeli Violations Of

ﺟﻣﻌﯾﺔ اﻟدراﺳﺎت اﻟﻌرﺑﯾﺔ Arab Studies Society ﻋﻠﻣﯾﺔ - ﻓﻛرﯾﺔ Scientific – Cultural ﻣرﻛز أﺑﺣﺎث اﻷراﺿﻲ Land Research Center اﻟﻘــدس Jerusalem The Monthly Report on the Israeli Violations of Palestinian Rights in the Occupied City of Jerusalem July- 2014 By: Monitoring Israeli Violations Team Land Research Center- Arab Studies Society Seventh Month of the Eighth Year ARAB STUDIES SOCIETY – Land Research Center (LRC) – Jerusalem Halhul – Main Road, Tel: 02-2217239 , Fax: 02-2290918 , P.O.Box: 35, E-mail: [email protected], URL: www.lrcj.org Israeli violations of Palestinians' rights to land and housing – July, 2014: Aggression Location Occurrence Demolition of houses and structures 2 - Self-demolition of a second floor in 1 a house 2 - Self demolition of a parking lot and Sur Baher basement Demolition threats 1 - Evacuation threat Jerusalem's Old City 1 House break-ins 91 - Break-ins for the sake of detaining The old city, Shu'fat, Beit Hanina, Sur Baher, 91 people, searching or vandalizing Umm Tuba, 'Anata, Abu Dis, al-Eizariya, Silwan Closures 24 - Set up of flying checkpoints The old city, Shu'fat, Beit Hanina, Anata, Abu 24 Dis, Silwan, ar-Ram, al-Eisawaya, at-Tur Colonial plans- residential units 243 - Approval of building new residential Colony of Pisgat Zeev 243 units Har Homa colony Colonists' attacks (in numbers) 12 - Setting fire to trees Jabal al-Mukabbir 20 - Attacks on individuals (including Beit Iksa, ar-Ram, Beit Hanina, Shu'fat, Jaffa 11 beating, torching, abducting) St., Sheikh Jarrah - Attacks on vehicles Sheikh Jarrah 7 - Attacks -

CHAPTER 3 the Classical School of Criminological Thought

The Classical CHAPTER 3 School of Criminological Thought Wally Skalij/Los Angeles Times/Getty Images distribute or post, copy, not Do Copyright ©2018 by SAGE Publications, Inc. This work may not be reproduced or distributed in any form or by any means without express written permission of the publisher. Introduction LEARNING A 2009 report from the Death Penalty Information Center, citing a study OBJECTIVES based on FBI data and other national reports, showed that states with the death penalty have consistently higher murder rates than states without the death penalty.4 The report highlighted the fact that if the death penalty were As you read this chapter, acting as a deterrent, the gap between these two groups of states would be consider the following topics: expected to converge, or at least lessen over time. But that has not been the case. In fact, this disparity in murder rates has actually grown over the past • Identify the primitive two decades, with states allowing the death penalty having a 42% higher types of “theories” murder rate (as of 2007) compared with states that do not—up from only explaining why 4% in 1990. individuals committed violent and other Thus, it appears that in terms of deterrence theory, at least when it comes deviant acts for most to the death penalty, such potential punishment is not an effective deterrent. of human civilization. This chapter deals with the various issues and factors that go into offend- • Describe how the ers’ decision-making about committing crime. While many would likely Age of Enlightenment anticipate that potential murderers in states with the death penalty would be drastically altered the deterred from committing such offenses, this is clearly not the case, given theories for how and the findings of the study discussed above. -

Ohio River -1783 to October 1790: A) Indians Have: I

1790-1795 . (5 Years) ( The Northwestern Indian War· . Situation & Events Leading Up To 1. Along the Ohio River -1783 to October 1790: A) Indians have: I. Killed, wounded, or taken prisoner: (1)1,500 men, women, or children. II. Stolen over 2,000 horses. III. Stolen property valued at over $50 thousand. 2. Presi.dent Washington - Orders - Governor of . .. Northwest Territory, Maj. Gen. Arthur St. Clair: A) Punish the Indians! ( 3. 1,450 Volunteers assemble at Cincinnati, Ohio: A) Commanded by Brig. G·eneral Josiah Harmer. 1790 - September 1. September 30, 1790 - Harmer's force starts out: A) Follow a trail of burnt Indian villages. 2. Indians are leading them deeper and deeper into Indian country. 3. Indians are led by Chief Little Turtle. ( 1"790 - October 1. October 19, 1790 - Col . .John Hardin is leading 21 Oof Harmer's Scouts: A) Ambushed! B) Cut to pieces! C) Route! 2. October 21, 1790 - Harmer's force: "A) Ambushed! B) Harmer retreats: I. Loses 180 killed & 33 wounded. C) November 4, 1790 - Survivors make it back to Cincinnati: - " -- ".. • •• "' : •••••• " ,or"""' .~..' •• , .~ I. Year later... Harmer resigns . ... -.: .~- ,: .... ~ 1791 1. Major General Arthur St. Clair - Takes command: . A) Old. B) Fat •.. C) No wilderness experience. D) NO idea .of how many Indians oppose him. E) NO idea of where the Indians are. F) Will not listen to advice. G) Will not take advice. H) Plans: I. Establish a string of Forts for 135 miles northwest of Cincinnati. 1791 - October 1. October 3, 1791 - .St. Clair's . force leaves Cincinnati: A) 2,000 men. B) Slow march. -

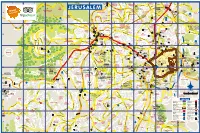

Jerusalem-Map.Pdf

H B S A H H A R ARAN H A E K A O RAMOT S K R SQ. G H 1 H A Q T V V HI TEC D A E N BEN G GOLDA MEIR I U V TO E R T A N U H M HA’ADMOR ESHKOL E 1 2 3 R 4 5 Y 6 DI ZAHA 7 MA H 8 E Z K A 9 INTCH. T A A MEGUR A E AR I INDUSTRY M SANHEDRIYYA GIV’AT Z L LOH T O O T ’A N Y A O H E PARA A M R N R T E A O 9 R (HAR HOZVIM) A Y V M EZEL H A A AM M AR HAMITLE A R D A A MURHEVET SUF I HAMIVTAR A G P N M A H M ET T O V E MISHMAR HAGEVUL G A’O A A N . D 1 O F A (SHAPIRA) H E ’ O IRA S T A A R A I S . D P A P A M AVE. Lev LEHI D KOL 417 i E V G O SH sh E k Y HAR O R VI ol L O I Sanhedrin E Tu DA M L AMMUNITION n n N M e E’IR L Tombs & Garden HILL l AV 436 E REFIDIM TAMIR JERUSALEM E. H I EZRAT T N K O EZRAT E E AV S M VE. R ORO R R L HAR HAMENUHOT A A A T E N A Z ’ Ammunition I H KI QIRYAT N M G TORA O 60 British Military (JEWISH CEMETERY) E HASANHEDRIN A N Hill H M I B I H A ZANS IV’AT MOSH H SANHEDRIYYA Cemetery QIRYAT SHEVA E L A M D Y G U TO MEV U S ’ L C E O Y M A H N H QIRYAT A IKH E . -

September 19 – International Talk Like a Pirate Day – Drill

September 19 – International Talk Like a Pirate Day – Drill “This is a Drill” Type of Event: Civil Disturbance: Invasion of pirates ---Blackbeard (and his crew – Black Ceaser, Israel Hands, Lieutenant Richards), Zheng Yi Sao, Jean Lafitte, Micajah and Wiley Harpe Pirates Duration of exercise: Wednesday, Sept 19 from 0000 to2400 (12:00am to 11:59pm) You may participate any time after that if you wish Place of occurrence: The Southeast Texas Region Objective: The goal of a drill is to request resources through WebEOC following your processes to fight against the Pirates and push them back into the sea so they never return. Participants: Sentinels and their users District Coordinators TDEM Critical Information Systems (CIS) SOC Methodology: WebEOC Event and STAR board Active Incident Name: Exercise 09/19/2018 International Talk Like Pirate Drill Exercise Directors: Black Dollie Winn (Janette Walker) , 832-690-8765 Thiefin’ Jackie Sneed (Jennifer Suter) Emergency Scenario: The above pirate have risen from their grave and traveled to the Gulf Coast during Tuesday night (9/18) and have already invaded the coastal counties (Matagorda, Brazoria, Galveston, and Chambers) and are working their way to the most northern counties (Walker, Colorado, Austin, Sabine). Each county they invade, they commandeer the liquor and supply chain stores as well as EOCs. Inject: AVAST Ye!! Ye land lovers, we gentleman o' fortunes be havin' risen from Davy Jones` Locker an' be are invadin' yer area an' plan t' commandeer all yer resources an' government land. We be tired o' th' water an' be movin' inland. We be havin' already invaded th' coastal counties an' movin' up t' th' northern counties. -

David Crockett: the Lion of the West Rev

Rev. April 2016 OSU-Tulsa Library archives Michael Wallis papers David Crockett: The Lion of the West Rev. April 2016 1:1 Wallis’s handwritten preliminary notes, references, etc. 110 pieces. 1:2 “A Day-to-Day Account of the Life of David Crockett during the Creek Indian War. Wallis’s typed chronology, 10p. 1:3-4 “A Day-to-Day Account of the Life of David Crockett at Shoal Creek, Lawrence County.” Wallis’s typed chronology, 211p. 1:5 “A Day-to-Day Account of the Life of David Crockett at Obion River, at first in Carroll, later in Gibson and Weakly County.” Wallis’s typed chronology, 28p. 1:6 “A Day-to-Day Account of the Life of David Crockett during his time in the Congress.” Wallis’s typed chronology, 23p. 1:7 David Crockett book [proposal]. Typescript in 3 versions. 1:8 David Crockett book outline. Typescript with handwritten notations, addressed to James Fitzgerald, 5p; plus another copy of same with attached note which reads, “Yes!” addressed to James Fitzgerald, 11 Sept 2007. Version 1 1:9 Typescript of an early draft with handwritten revisions, additions, and editorial marks and comments; p1-57. 1:10 p58-113. 1:11 p114-170. Version 2 1:12 Photocopied typescript of chapters 16-28, with extensive handwritten revisions and corrections. Version 3 1:13 “Davey Crockett: The Lion of the West.” Typed cover memo by Phil Marino (W.W. Norton) with additional handwritten comments, written to an unidentified recipient, p1-4. Typed comments by Phil Marino written to Michael Wallis, p5, followed by an unedited copy of p10-144.