Microfilms International 300 N

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

May 2020 Personnel Actions

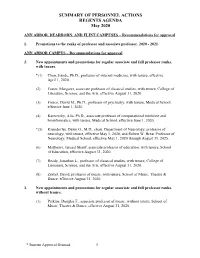

SUMMARY OF PERSONNEL ACTIONS REGENTS AGENDA May 2020 ANN ARBOR, DEARBORN, AND FLINT CAMPUSES – Recommendations for approval 1. Promotions to the ranks of professor and associate professor, 2020 - 2021. ANN ARBOR CAMPUS – Recommendations for approval 2. New appointments and promotions for regular associate and full professor ranks, with tenure. *(1) Chen, Jiande, Ph.D., professor of internal medicine, with tenure, effective April 1, 2020. (2) Foster, Margaret, associate professor of classical studies, with tenure, College of Literature, Science, and the Arts, effective August 31, 2020. (3) Fresco, David M., Ph.D., professor of psychiatry, with tenure, Medical School, effective June 1, 2020. (4) Karnovsky, Alla, Ph.D., associate professor of computational medicine and bioinformatics, with tenure, Medical School, effective June 1, 2020. *(5) Kleindorfer, Dawn O., M.D., chair, Department of Neurology, professor of neurology, with tenure, effective May 1, 2020, and Robert W. Brear Professor of Neurology, Medical School, effective May 1, 2020 through August 31, 2025. (6) Matthews, Jamaal Sharif, associate professor of education, with tenure, School of Education, effective August 31, 2020. (7) Ready, Jonathan L., professor of classical studies, with tenure, College of Literature, Science, and the Arts, effective August 31, 2020. (8) Zerkel, David, professor of music, with tenure, School of Music, Theatre & Dance, effective August 31, 2020. 3. New appointments and promotions for regular associate and full professor ranks, without tenure. (1) Perkins, Douglas F., associate professor of music, without tenure, School of Music, Theatre & Dance, effective August 31, 2020. * Interim Approval Granted 1 SUMMARY OF PERSONNEL ACTIONS REGENTS AGENDA May 2020 ANN ARBOR CAMPUS – Recommendations for approval 4. -

Israël Veut Un « Changement Complet » De La Politique Menée Par L'olp

LeMonde Job: WMQ0208--0001-0 WAS LMQ0208-1 Op.: XX Rev.: 01-08-97 T.: 11:23 S.: 111,06-Cmp.:01,11, Base : LMQPAG 27Fap:99 No:0328 Lcp: 196 CMYK CINQUANTE-TROISIÈME ANNÉE – No 16333 – 7,50 F SAMEDI 2 AOÛT 1997 FONDATEUR : HUBERT BEUVE-MÉRY – DIRECTEUR : JEAN-MARIE COLOMBANI Les athlètes Israël veut un « changement complet » à Athènes de la politique menée par l’OLP Rigor Mortis a Brigitte Aubert Participation record Benyamin Nétanyahou exige de Yasser Arafat qu’il éradique le terrorisme a aux championnats ISRAÉLIENS et responsables de Jérusalem. Les premiers accusent Le premier ministre a mis Yasser maine. « On ne peut faire avancer du monde l’Autorité palestinienne se sont l’OLP de ne pas en faire assez dans Arafat en demeure d’éradiquer le le processus diplomatique alors que renvoyés, jeudi 31 juillet, la res- la lutte contre le terrorisme ; les terrorisme et a juré qu’il n’y aurait l’Autorité palestinienne ne prend une nouvelle inédite ponsabilité de l’attentat qui, la seconds affirment que la politique pas de reprise des conversations pas les mesures minimales qu’elle qui s’ouvrent samedi veille, a fait quinze morts et plus du gouvernement de Benyamin israélo-palestiniennes tant qu’Is- s’est engagée à prendre contre les de cent cinquante blessés sur un Nétanyahou favorise la montée raël ne jugerait pas l’action de foyers du terrorisme », a dit M. Né- dames a des marchés les plus populaires de des extrémistes palestiniens. l’OLP satisfaisante dans ce do- tanyahou. « Il faut un changement du noir La pollution peut complet de politique de la part des Palestiniens, une campagne vigou- perturber les épreuves reuse, systématique et immédiate pour éliminer le terrorisme », a-t-il Les Dames a lancé, jeudi soir, à la télévision. -

Sixteenth Century Society and Conference S Thursday, 17 October to Sunday, 20 October 2019

Sixteenth Century Society and Conference S Thursday, 17 October to Sunday, 20 October 2019 Cover Picture: Hans Burgkmair, Portrait of the Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian I (1459–1519) (1518). Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam. Sixteenth Century Society & Conference 17–20 October 2019 2019 OFFICERS President: Walter S. Melion Vice-President: Andrew Spicer Past-President: Kathleen M. Comerford Executive Director: Bruce Janacek Financialo Officer: Eric Nelson COUNCIL Class of 2019: Brian Sandberg, Daniel T. Lochman, Suzanne Magnanini, Thomas L. Herron Class of 2020: David C. Mayes, Charles H. Parker, Carin Franzén, Scott C. Lucas Class of 2021: Sara Beam, Jasono Powell, Ayesha Ramachandran, Michael Sherberg ACLS REPRESENTATIVE oKathryn Edwards PROGRAM COMMITTEE Chair: Andrew Spicer Art History: James Clifton Digital Humanities: Suzanne Sutherland English Literature: Scott C. Lucas French Literature: Scott M. Francis German Studies: Jennifer Welsh History: Janis M. Gibbs Interdisciplinary: Andrew Spicer Italian Studies: Jennifer Haraguchi Pedagogy: Chris Barrett Science and Medicine: Chad D. Gunnoe Spanish and Latin American Studies: Nieves Romero-Diaz Theology:o Rady Roldán-Figueroa NOMINATING COMMITTEE Amy E. Leonard, Beth Quitslund, Jeffreyo R. Watt, Thomas Robisheaux, Elizabeth A. Lehfeldt ENDOWMENT CHAIRS Susano Dinan and James Clifton SIXTEENTH CENTURY SOCIETY & CONFERENCE FIFTIETH ANNIVERSARY COMMITTEE Sheila ffolliott (Chair) Kathryn Brammall, Kathleen M. Comerford, Gary Gibbs, Whitney A. M. Leeson, Ray Waddington, Merry Wiesner-Hanks Waltero S. Melion (ex officio) 2019 SCSC PRIZE COMMITTEES Founders’ Prize Karen Spierling, Stephanie Dickey, Wim François Gerald Strauss Book Prize David Luebke, Jesse Spohnholz, Jennifer Welsh Bainton Art & Music History Book Prize Bret Rothstein, Lia Markey, Jessica Weiss Bainton History/Theology Book Prize Barbara Pitkin, Tryntje Helfferich, Haruko Ward Bainton Literature Book Prize Deanne Williams, Thomas L. -

A Saintly Woman Is Not a Starving Woman: Parrhesia in “Birgitta's

A Saintly Woman is Not a Starving Woman: Parrhesia in “Birgitta’s Heart is a Pot of Delicious Food” Judith Lanzendorfer College of Arts, Humanities, and Social Sciences, English Department University of Findlay 1000 N. Main St. Findlay, 45840, Ohio, USA e-mail: [email protected] Abstract: This article focuses on Chapter 54, “Birgitta’s Heart is a Pot of Delicious Food”, of Birgitta of Sweden’s Revelationes extravagantes. This vision is striking in its use of parrhesis, the idea of speaking “truth to power”, particularly because this vision is less edited by an amanuensis than any other section of Birgitta’s works. Also striking in this vision is the use of food, which is often presented in medieval women’s visionary texts as a temptation; in Chapter 54 food is framed in a positive way. It is only ash from a fire that the food is cooked over, framed as worldly temptation, that is problematic. As such, the emphasis in the vision is balance between an understanding of the secular world and how it can coexist with one’s spiritual nature. Keywords: Birgitta of Sweden, Parrhesis, Foodways, Visionary, Authorial Voice In Chapter 54 of Revelationes extravagantes Birgitta of Sweden recounts a vision which is now known as “Birgitta’s Heart is a Pot of Delicious Food”. In this vision, Birgitta relates that: Once when Lady Birgitta was at prayer, she saw before her in a spiritual vision a small fire with a small pot of food above it, and delicious food in the pot. She also saw a man splendidly dressed in purple and gold. -

The French Recension of Compilatio Tertia

The Catholic University of America, Columbus School of Law CUA Law Scholarship Repository Scholarly Articles and Other Contributions Faculty Scholarship 1975 The French Recension of Compilatio Tertia Kenneth Pennington The Catholic University of America, Columbus School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.edu/scholar Part of the Religion Law Commons Recommended Citation Kenneth Pennington, The French Recension of Compilatio Tertia, 5 BULL. MEDIEVAL CANON L. 53 (1975). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at CUA Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Scholarly Articles and Other Contributions by an authorized administrator of CUA Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The French recension of Compilatio tertia* Petrus Beneventanus compiled a collection of Pope Innocent III's decretal letters in 1209 which covered the first twelve years of Innocent's pontificate. In 1209/10, Innocent authenticated the collection and sent it to the masters and students in Bologna. His bull (Devotioni vestrae), said Innocent, was to remove any scruples that the lawyers might have about using the collection in the schools and courts. The lawyers called the collection Compilatio tertia; it was the first officially sanctioned collection of papal decretals and has become a benchmark for the growing sophistication of European jurisprudence in the early thirteenth century.1 The modern investigation of the Compilationes antiquae began in the sixteenth century when Antonius Augustinus edited the first four compilations and publish- ed them in 1576. His edition was later republished in Paris (1609 and 1621) and as part of an Opera omnia in Lucca (1769). -

Catholic Clergy Sexual Abuse Meets the Civil Law Thomas P

Fordham Urban Law Journal Volume 31 | Number 2 Article 6 2004 Catholic Clergy Sexual Abuse Meets the Civil Law Thomas P. Doyle Catholic Priest Stephen C. Rubino Ross & Rubino LLP Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/ulj Part of the Religion Law Commons Recommended Citation Thomas P. Doyle and Stephen C. Rubino, Catholic Clergy Sexual Abuse Meets the Civil Law, 31 Fordham Urb. L.J. 549 (2004). Available at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/ulj/vol31/iss2/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by FLASH: The orF dham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. It has been accepted for inclusion in Fordham Urban Law Journal by an authorized editor of FLASH: The orF dham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CATHOLIC CLERGY SEXUAL ABUSE MEETS THE CIVIL LAW Thomas P. Doyle, O.P., J.C.D.* and Stephen C. Rubino, Esq.** I. OVERVIEW OF THE PROBLEM In 1984, the Roman Catholic Church began to experience the complex and highly embarrassing problem of clergy sexual miscon- duct in the United States. Within months of the first public case emerging in Lafayette, Louisiana, it was clear that this problem was not geographically isolated, nor a minuscule exception.' In- stances of clergy sexual misconduct surfaced with increasing noto- riety. Bishops, the leaders of the United States Catholic dioceses, were caught off guard. They were unsure of how to deal with spe- cific cases, and appeared defensive when trying to control an ex- panding and uncontrollable problem. -

Heresy and Error Eric Marshall White Phd [email protected]

Southern Methodist University SMU Scholar Bridwell Library Publications Bridwell Library 9-20-2010 Heresy and Error Eric Marshall White PhD [email protected] Rebecca Howdeshell Southern Methodist University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.smu.edu/libraries_bridwell_publications Part of the Ancient, Medieval, Renaissance and Baroque Art and Architecture Commons, Art and Materials Conservation Commons, Book and Paper Commons, European History Commons, and the History of Religion Commons Recommended Citation White, Eric Marshall PhD and Howdeshell, Rebecca, "Heresy and Error" (2010). Bridwell Library Publications. 1. https://scholar.smu.edu/libraries_bridwell_publications/1 This document is brought to you for free and open access by the Bridwell Library at SMU Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Bridwell Library Publications by an authorized administrator of SMU Scholar. For more information, please visit http://digitalrepository.smu.edu. “Heresy and Error” THE ECCLESIASTICAL CENSORSHIP OF BOOKS 1400–1800 “Heresy and Error” THE ECCLESIASTICAL CENSORSHIP OF BOOKS 1400–1800 Eric Marshall White Curator of Special Collections Bridwell Library Perkins School of Theology Southern Methodist University 2010 Murray, Sequel to the English Reader, 1839 (exhibit 55). Front cover: Erasmus, In Novum Testamentum annotationes, 1555 (exhibit 1). Title page and back cover: Boniface VIII, Liber sextus decretalium, 1517 (exhibit 46). Copyright 2010 Bridwell Library, Perkins School of Theology, Southern Methodist University. All rights reserved. FROM ITS INCEPTION THE EARLY CHRISTIAN CHURCH sought to suppress books believed to contain heretical or erroneous teachings. With the development of the printing press during the latter half of the fifteenth century, Christian authorities in Europe became increasingly aware of the need to control the mass production of unfamiliar and potentially unacceptable texts. -

Vendredi 24 Janvier 2020

Vendredi 24 Janvier 2020 à 14 h LIVRES ANCIENS ET MODERNES dont belle bibliothèque régionale BELLE COLLECTION D’AUTOGRAPHES VIEUX PAPIERS Les lots 1 à 27 sont présentés par Emmanuel LHERMITTE, Expert à Paris (tél. 06 77 79 48 43) Les autographes 28 à 42 sont présentés par Michel BOURDIN (tél. 06 75 77 23 60) Exposition : le matin de 9 h à 12 h détails sur : www.interencheres.com/21002 vente live Sylvain GAUTIER, Commissaire-Priseur 122 avenue Victor Hugo 21000 Dijon Tél : 03 80 560 560 – Fax : 03 80 560 561 – [email protected] Maison de Ventes aux Enchères Volontaires agréée sous le n° 2002-136 1 Conditions de vente La vente sera faite au comptant. Les acquéreurs règleront en sus des enchères les frais et taxes suivants : - 21 % TTC pour les enchères en salle - 24 % TTC pour les ordres d’achat, les enchères téléphoniques, les « ordres d’achats secrets » et les enchères en direct sur interencheres-live.com La délivrance des objets se fera une fois le paiement complet et effectif. Le paiement par carte bancaire est accepté, en cas de paiement par chèque ou par virement bancaire, le transfert de propriété ne se fera qu’après encaissement. Les acheteurs ne résidant pas en France ne pourront prendre livraison de leur achat qu’après règlement par SWIFT ou virement bancaire (additionné des frais bancaires). Les règlements et enlèvements sont attendus sous huitaine. Au-delà, des pénalités de retard et des frais de stockage seront facturés (tarif par lot : 1 € HT par jour les 5 premiers jours, puis 5 €, 9 € ou 16 € HT par jour à partir du 6ème jour, selon l'encombrement du lot). -

First Execution for Witchcraft in Ireland

Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology Volume 7 | Issue 6 Article 5 1917 First Execution for Witchcraft in rI eland William Renwick Riddell Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/jclc Part of the Criminal Law Commons, Criminology Commons, and the Criminology and Criminal Justice Commons Recommended Citation William Renwick Riddell, First Execution for Witchcraft in rI eland, 7 J. Am. Inst. Crim. L. & Criminology 828 (May 1916 to March 1917) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology by an authorized editor of Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. THE FIRST EXECUTION FOR WITCHCRAFT IN IRELAND I WILLIAM RENWICK RIDDELL We of the present age find it very difficult to enter into the atmosphere of the times in which witchcraft was a well recognized and not uncommon crime. It is a never-ceasing cause of wonderment to us that the whole Christian world, Emperor King and Noble, Pope Cardinal and Bishop, all shared in what we consider an obvious de- lusion. Thousands perished at the stake for this imaginary crime, no few of them in the Isle of Saints itself. The extraordinary story of the first auto de fe in Ireland will well repay perusal, both from its intrinsic interest and as showing the practice of criminal law at that time and place and in that kind of crime, 2 as well as indicating the claims of the Church in such cases. -

Warwick.Ac.Uk/Lib-Publications Manuscript Version: Author's

Manuscript version: Author’s Accepted Manuscript The version presented in WRAP is the author’s accepted manuscript and may differ from the published version or Version of Record. Persistent WRAP URL: http://wrap.warwick.ac.uk/114589 How to cite: Please refer to published version for the most recent bibliographic citation information. If a published version is known of, the repository item page linked to above, will contain details on accessing it. Copyright and reuse: The Warwick Research Archive Portal (WRAP) makes this work by researchers of the University of Warwick available open access under the following conditions. Copyright © and all moral rights to the version of the paper presented here belong to the individual author(s) and/or other copyright owners. To the extent reasonable and practicable the material made available in WRAP has been checked for eligibility before being made available. Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. Publisher’s statement: Please refer to the repository item page, publisher’s statement section, for further information. For more information, please contact the WRAP Team at: [email protected]. warwick.ac.uk/lib-publications 1 Definitive version for Erudition and the Republic of Letters Feb 2019 How the Sauce Got to be Better -

The Dramaturgy of Marivaux: Three Elements of Technique

72-4653 SPINELLI, Donald Carmen, 1942- THE DRAMATURGY OF MARIVAUX: THREE ELEMENTS OF TECHNIQUE. The Ohio State University, Ph.D., 1971 Language and Literature, modern University Microfilms,A XE R O X Company, Ann Arbor, Michigan © 1 9 7 1 Donald Carmen Spinelli ALL RIGHTS RESERVED THE DRAMATURGY OF MARIVAUX* THREE ELEMENTS OF TECHNIQUE DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Donald C. Spinelli, B.A., M.A. ****** The Ohio State University 1971 Approved by Adviser nt of Romance Languages PLEASE NOTE: Some Pages have Indistinct print. Filmed as received. UNIVERSITY MICROFILMS TO MY MOTHER AND FATHER ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to take this opportunity to express my gratitude to some of the people who have made this work possible. Professors Pierre Aubery and V. Frederick Koenig took a personal interest in my academic progress while I was at the University of Buffalo and both en couraged me to continue my studies in French, At Ohio State University I am grateful to my ad visor* Professor Hugh M. Davidson* whose seminar first interested me in Marivaux. Professor Davidson*s sound advice* helpful comments* clarifying suggestions and tactful criticism while discussing the manuscript gave direction to this study and were invaluable in bringing it to its fruition. 1 must thank Emily Cronau who often gave of her own time to type and to help edit this dissertation! but most of all I am grateful for her just being there when she was needed during the past few years. -

Report of Evaluation

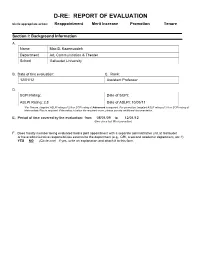

D-RE: REPORT OF EVALUATION Circle appropriate action: Reappointment Merit Increase Promotion Tenure Section I: Background Information A. Name Max B. Kazemzadeh Department Art, Communication & Theater School Gallaudet University B. Date of this evaluation: C. Rank: 12/01/12 Assistant Professor D. SCPI Rating: Date of SCPI: ASLPI Rating: 2.8 Date of ASLPI: 10/05/11 *For Tenure, targeted ASLPI rating of 2.5 or SCPI rating of Advanced is required. For promotion, targeted ASLP rating of 3.0 or SCPI rating of Intermediate Plus is required. If the rating is below the required score, please provide additional documentation. E. Period of time covered by the evaluation: from _08/01/09_ to __12/01/12__ (time since last MI or promotion) F. Does faculty member being evaluated hold a joint appointment with a separate administrative unit at Gallaudet or have administrative responsibilities external to the department (e.g., GRI, a second academic department, etc.?) YES NO (Circle one) If yes, write an explanation and attach it to this form. Section II: Teaching From UF Guidelines, Section 2.1.2.1: Teaching competence includes both expertise in the faculty member's field and the ability to impart knowledge deriving from that field to Gallaudet students. A competent teacher must possess the ability to communicate course content clearly and effectively; he/she must also be available to the students individually, responsive to their academic needs, and flexible enough to adapt curriculum and methodology to those needs. [Effective communication as intended by this heading is separate from and in addition to proficiency in Sign Communication as outlined in Section 2.1.2.4.] A.