Native Religions and Seventh-Day Adventists in the West-Central Africa Division

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Igbo Man's Belief in Prayer for the Betterment of Life Ikechukwu

Igbo man’s Belief in Prayer for the Betterment of Life Ikechukwu Okodo African & Asian Studies Nnamdi Azikiwe University, Awka Abstract The Igbo man believes in Chukwu strongly. The Igbo man expects all he needs for the betterment of his life from Chukwu. He worships Chukwu traditionally. His religion, the African Traditional Religion, was existing before the white man came to the Igbo land of Nigeria with his Christianity. The Igbo man believes that he achieves a lot by praying to Chukwu. It is by prayer that he asks for the good things of life. He believes that prayer has enough efficacy to elicit mercy from Chukwu. This paper shows that the Igbo man, to a large extent, believes that his prayer contributes in making life better for him. It also makes it clear that he says different kinds of prayer that are spontaneous or planned, private or public. Introduction Since the Igbo man believes in Chukwu (God), he cannot help worshipping him because he has to relate with the great Being that made him. He has to sanctify himself in order to find favour in Chukwu. He has to obey the laws of his land. He keeps off from blood. He must not spill blood otherwise he cannot stand before Chukwu to ask for favour and succeed. In spite of that it can cause him some ill health as the Igbo people say that those whose hands are bloody are under curses which affect their destines. The Igboman purifies himself by avoiding sins that will bring about abominations on the land. -

An Analysis of Adventist Mission Methods in Brazil in Relationship to a Christian Movement Ethos

Andrews University Digital Commons @ Andrews University Dissertations Graduate Research 2016 An Analysis of Adventist Mission Methods in Brazil in Relationship to a Christian Movement Ethos Marcelo Eduardo da Costa Dias Andrews University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dissertations Part of the Missions and World Christianity Commons Recommended Citation Costa Dias, Marcelo Eduardo da, "An Analysis of Adventist Mission Methods in Brazil in Relationship to a Christian Movement Ethos" (2016). Dissertations. 1598. https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dissertations/1598 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Research at Digital Commons @ Andrews University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Andrews University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ABSTRACT AN ANALYSIS OF ADVENTIST MISSION METHODS IN BRAZIL IN RELATIONSHIP TO A CHRISTIAN MOVEMENT ETHOS by Marcelo E. C. Dias Adviser: Bruce Bauer ABSTRACT OF GRADUATE RESEARCH Dissertation Andrews University Seventh-day Adventist Theological Seminary Title: AN ANALYSIS OF ADVENTIST MISSION METHODS IN BRAZIL IN RELATIONSHIP TO A CHRISTIAN MOVEMENT ETHOS Name of researcher: Marcelo E. C. Dias Name and degree of faculty chair: Bruce Bauer, DMiss Date completed: May 2016 In a little over 100 years, the Seventh-day Adventist Church in Brazil has grown to a membership of 1,447,470 (December 2013), becoming the country with the second highest total number of Adventists in the world. Very little academic research has been done to study or analyze the growth and development of the Adventist church in Brazil. -

Southwest Bahia Mission Facade, 2019

Southwest Bahia Mission facade, 2019. Photo courtesy of Nesias Joaquim dos Santos. Southwest Bahia Mission NESIAS JOAQUIM DOS SANTOS Nesias Joaquim dos Santos The Southwest Bahia Mission (SWBA) is an administrative unit of the Seventh-day Adventist Church (SDA) located in the East Brazil Union Mission. Its headquarters is in Juracy Magalhães Street, no. 3110, zip code 45023-490, district of Morada dos Pássaros II, in the city of Vitoria da Conquista, in Bahia State, Brazil.1 The city of Vitória da Conquista, where the administrative headquarters is located, is also called the southwestern capital of Bahia since it is one of the largest cities in Bahia State. With the largest geographical area among the five SDA administrative units in the State of Bahia, SWBA operates in 166 municipalities.2 The population of this region is 3,943,982 inhabitants3 in a territory of 99,861,370 sq. mi. (258,639,761 km²).4 The mission oversees 42 pastoral districts with 34,044 members meeting in 174 organized churches and 259 companies. Thus, the average is one Adventist per 116 inhabitants.5 SWBA manages five schools. These are: Escola Adventista de Itapetinga (Itapetinga Adventist School) in the city of Itapetinga with 119 students; Colégio Adventista de Itapetinga (Itapetinga Adventist Academy), also in Itapetinga, with 374 students; Escola Adventista de Jequié (Jequié Adventist School) with 336 students; Colégio Adventista de Barreiras (Barreiras Adventist Academy) in Barreiras with 301 students; and Conquistense Adventist Academy with 903 students. The total student population is 2,033.6 Over the 11 years of its existence, God has blessed this mission in the fulfillment of its purpose, that is, the preaching of the gospel to all the inhabitants in the mission’s territory. -

DIANA PATON & MAARIT FORDE, Editors

diana paton & maarit forde, editors ObeahThe Politics of Caribbean and Religion and Healing Other Powers Obeah and Other Powers The Politics of Caribbean Religion and Healing diana paton & maarit forde, editors duke university press durham & london 2012 ∫ 2012 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper $ Designed by Katy Clove Typeset in Arno Pro by Keystone Typesetting, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data appear on the last printed page of this book. Duke University Press gratefully acknowledges the support of Newcastle University, which provided funds toward the production of this book. Foreword erna brodber One afternoon when I was six and in standard 2, sitting quietly while the teacher, Mr. Grant, wrote our assignment on the blackboard, I heard a girl scream as if she were frightened. Mr. Grant must have heard it, too, for he turned as if to see whether that frightened scream had come from one of us, his charges. My classmates looked at me. Which wasn’t strange: I had a reputation for knowing the answer. They must have thought I would know about the scream. As it happened, all I could think about was how strange, just at the time when I needed it, the girl had screamed. I had been swimming through the clouds, unwillingly connected to a small party of adults who were purposefully going somewhere, a destination I sud- denly sensed meant danger for me. Naturally I didn’t want to go any further with them, but I didn’t know how to communicate this to adults and ones intent on doing me harm. -

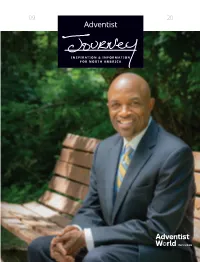

Adventist Journey 09/20

09 20 INSPIRATION & INFORMATION FOR NORTH AMERICA INCLUDED Adventist Journey Contents 04 Feature 13 Perspective Meet the New NAD President Until All Lives Matter . 08 NAD News Briefs My Journey In my administrative role at the NAD, I still do evangelism. I do at least one [series] a year and I still love it. Sometimes, through all the different committees and policies and that part of church life, you have to work to keep connected to the front-line ministries—where people are being transformed by the power of the gospel. Visit vimeo.com/nadadventist/ajalexbryant for more of Bryant’s story. G. ALEXANDER BRYANT, new president of the North American Division Cover Photo by Dan Weber Dear Reader: The publication in your hands represents the collaborative efforts of the ADVENTIST JOURNEY North American Division and Adventist World magazine, which follows Adventist Journey Editor Kimberly Luste Maran (after page 16). Please enjoy both magazines! Senior Editorial Assistant Georgia Damsteegt Art Direction & Design Types & Symbols Adventist Journey (ISSN 1557-5519) is the journal of the North American Division of the General Conference of Seventh-day Adventists. The Northern Asia-Pacific Division of the General Conference of Seventh-day Consultants G. Earl Knight, Mark Johnson, Dave Weigley, Adventists is the publisher. It is printed monthly by the Pacific Press® Publishing Association. Copyright Maurice Valentine, Gary Thurber, John Freedman, © 2020. Send address changes to your local conference membership clerk. Contact information should be available through your local church. Ricardo Graham, Ron C. Smith, Larry Moore Executive Editor, Adventist World Bill Knott PRINTED IN THE U.S.A. -

Pentecostalism, the Akan Religion and the Good Life

Pentecostalism, the Akan Religion and the Good Life Joseph Quayesi-Amakye* Introduction It was Geoffrey Parrinder who noted that a comparative study in other religions in Africa can help in understanding attitudes behind traditional religion.1 For example, the emergence of Christian prophetism in the tropics reveals important elements in traditional religion. With the Church of Pentecost (COP) as my main case, I will examine and assess the Ghanaian Pentecostal ideas about the good life. I will also demonstrate the interface between the Akan traditional religio-culture and Pentecostals’ inherited Christian tradition in their ideas about the good life. I will then propose a contextualisation of the ideas of the good life. The Akan people constitute about 44% of the total population of Ghana. Their language and culture pervade through much of the nation’s culture, including the Christian religion. Hence, a discussion of this nature must entail a discussion on how the Akan conceive goodness. We will ask: In what ways does the Ghanaian Pentecostal understanding of God’s goodness and the good life show the impingement of the Akan primal religion? Ghanaian Pentecostalism began with the initial work of Apostle Peter Newman Anim in 1917. Later in 1937, the British Apostolic Church sent a resident missionary, Pastor James McKeown, to help Anim with the administration of his organisation.2 The short-lived relationship would later result in three major churches, (Christ Apostolic Church, The Apostolic Church, and the Church of Pentecost), which together with the American Assemblies of God church constitute the main part of classical Pentecostalism in Ghana. -

Cth 821 Course Title: African Traditional Religious Mythology and Cosmology

NATIONAL OPEN UNIVERSITY OF NIGERIA SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SOCIAL SCIENCES COURSE CODE: CTH 821 COURSE TITLE: AFRICAN TRADITIONAL RELIGIOUS MYTHOLOGY AND COSMOLOGY 1 Course Code: CTH 821 Course Title: African Traditional Religious Mythology and Cosmology Course Developer: Rev. Fr. Dr. Michael .N. Ushe Department of Christian Theology School of Arts and Social Sciences National Open University of Nigeria, Lagos Course Writer: Rev. Fr. Dr. Michael .N. Ushe Department of Christian Theology School of Arts and Social Sciences National Open University of Nigeria, Lagos Programme Leader: Rev. Fr. Dr. Michael .N. Ushe Department of Christian Theology School of Arts and Social Sciences National Open University of Nigeria, Lagos Course Title: CTH 821 AFRICAN TRADITIONAL RELIGIOUS MYTHOLOGY AND COSMOLOGY COURSE DEVELOPER/WRITER: Rev. Fr. Dr. Ushe .N. Michael 2 National Open University of Nigeria, Lagos COURSE MODERATOR: Rev. Fr. Dr. Mike Okoronkwo National Open University of Nigeria, Lagos PROGRAMME LEADER: Rev. Fr. Dr. Ushe .N. Michael National Open University of Nigeria, Lagos CONTENTS PAGE Introduction…………………………………………………………………………………… …...i What you will learn in this course…………………………………………………………….…i-ii 3 Course Aims………………………………………………………..……………………………..ii Course objectives……………………………………………………………………………...iii-iii Working Through this course…………………………………………………………………….iii Course materials…………………………………………………………………………..……iv-v Study Units………………………………………………………………………………………..v Set Textbooks…………………………………………………………………………………….vi Assignment File…………………………………………………………………………………..vi -

Afro-Jamaican Religio-Cultural Epistemology and the Decolonization of Health

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School March 2020 Mystic Medicine: Afro-Jamaican Religio-Cultural Epistemology and the Decolonization of Health Jake Wumkes University of South Florida Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the African Studies Commons, Other Languages, Societies, and Cultures Commons, and the Religion Commons Scholar Commons Citation Wumkes, Jake, "Mystic Medicine: Afro-Jamaican Religio-Cultural Epistemology and the Decolonization of Health" (2020). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/8311 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Mystic Medicine: Afro-Jamaican Religio-Cultural Epistemology and the Decolonization of Health by Jake Wumkes A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Latin American, Caribbean, and Latino Studies Department of School of Interdisciplinary Global Studies College of Arts & Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Bernd Reiter, Ph.D. Tori Lockler, Ph.D. Omotayo Jolaosho, Ph.D. Date of Approval: February 27, 2020 Keywords: Healing, Rastafari, Coloniality, Caribbean, Holism, Collectivism Copyright © 2020, Jake Wumkes Table of Contents Abstract ........................................................................................................................... -

With This Issue ADVENTIST WORLD

ADVENTISTwith this FREEWORLD issue ollowing the earthquake tragedy that struck South Asia, ADRA-UK has launched an appeal to raise funds to bring immediate relief to the victims. ADRA-UK is 95% of the buildings in Bagh were co-ordinating its efforts with demolished by the quake Fother donor offices and ADRA- Trans-Europe to respond to this major disaster. The ADRA network is focusing efforts on Pakistan, which has been most affected by the disaster. ADRA has had a long-term presence in Pakistan, providing development proj- ects in the affected regions since 1984. The ADRA-Pakistan office has already commenced relief activities with the provision of food, medical supplies and shelter. The ADRA network was mobilised into action within hours of the earthquake, which occurred at 8:50 on Saturday 8 October, and measured 7.6 on the Richter Scale. The writer was in contact with ADRA-International and Trans- Europe (which covers Pakistan as one of its field territories) by > 16 It takes a great man to deal with failure and time to make sure I had not Christmas shoebox defeat. It takes a very, very great man to deal with misread something. No. There success and victory. David was not that great. it was. I read as far as verse I Victorious over the Syrians, military genius 15 where it says that Nathan David felt so confident about capturing Rabbah ‘went home’, and I thought, appeal (Amman) that he sent Joab to do it while he stayed ‘Right, that’s it’; and I lost Is God All boxes need to be received by 1 December in home. -

On the Rationality of Traditional Akan Religion: Analyzing the Concept of God

Majeed, H. M/ Legon Journal of the Humanities 25 (2014) 127-141 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/ljh.v25i1.7 On the Rationality of Traditional Akan Religion: Analyzing the Concept of God Hasskei M. Majeed Lecturer, Department of Philosophy and Classics, University of Ghana, Legon Abstract This paper is an attempt to show how logically acceptable (or rational) belief in Traditional Akan religion is. The attempt is necessitated by the tendency by some scholars to (mis) treat all religions in a generic sense; and the potential which Akan religion has to influence philosophical debates on the nature of God and the rationality of belief in God – generally, on the practice of religion. It executes this task by expounding some rational features of the religion and culture of the Akan people of Ghana. It examines, in particular, the concept of God in Akan religion. This paper is therefore a philosophical argument on the sacred and institutional representation of what humans have come to refer to as “religious.” Keywords: rationality; good; Akan religion; God; worship By “Traditional Akan religion,” I mean the indigenous system of sacred beliefs, values, and practices of the Akan people of Ghana1. This is not to say, however, that the Akans are only found in Ghana. Traditional Akan religion has features that distinguish it from other African religions, and more so from non-African ones. This seems to underscore the point that religious practice varies across the cultures of the world, although all religions could share some common attributes. Yet, some philosophers and religionists, for instance, have not been measured in their presentation of the general features of religion. -

Traditional African Religion:A Resource Unit

1 DOCUMENT RESUME ED 037 586 24 AA 000 519 AUTHOR Garland, WilliamE. TITLE Traditional African Religion:A Resource Unit. INSTITUTION Carnegie-Mellom Univ.,Tittsburgh,Pa. Project Africa. SPONS AGENCY Office of Education,Washington, D.C. BUREAU NO BR-74*0724 PUB DATE 70 NOTE 73p. EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF-$0.50 HC-$3.75 DESCRIPTORS *African Culture, AfricanHistory, *Annotated Bibliographies, High SchoolStudents, Instructional MaterialS, *Non WesternCivilization, *Religious Conflict, *Social StudiesUnits IDENTIFIERS *Project'Africa ABSTRACT This resource unit isbased on researchconducted by Lynn Mitchell and ErnestValenzuela experienced classroomteachers of African history andculture. The unit consistsof an introduction by Mr. Garland and twomajor Parts.Part I is an annotated bibli°graPbY of selectedsources on various aspects of traditional African Religion useful in classroom study. Part.II consists ofa model teaching unit of two weeksduration, builton an inguirY teaching strategy andutilizes a variety of audio as and visualas well written materials designedfor use by high school teaching plan and students- The instructional materialswhich comprisethisfunit have not been tested inany classroom setting but are presented model of one as,a possiblewayto introduce astudyof traditional African religion. Related documentsare ED 023 692, ED 023 693, ED 030010, ED. 032 324-ED 032 327.and ED 033 249.(Author/LS) ,P ' .N , TRADITIONAL AFRICAN RELIGION A RESOURCE UNIT P1F/JECT AFRICA 1910 The research reported herein WEI perforised pursuant to a contract with the United States Department of HealthEducation and Wetfare Office of Education * 41, NM 4 Project Africa Balterlia11, Carnegie-Yie/lon University Schen ley Park Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania 15213 . .. .. Preface This resource unit has been preparedby William E. -

Ellen White's Counsel to Leaders: Identification and Synthesis of Principles, Experiential Application, and Comparison with Current Leadership Literature

Andrews University Digital Commons @ Andrews University Professional Dissertations DMin Graduate Research 2006 Ellen White's Counsel To Leaders: Identification And Synthesis Of Principles, Experiential Application, And Comparison With Current Leadership Literature Cynthia Ann Tutsch Andrews University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dmin Part of the Practical Theology Commons Recommended Citation Tutsch, Cynthia Ann, "Ellen White's Counsel To Leaders: Identification And Synthesis Of Principles, Experiential Application, And Comparison With Current Leadership Literature" (2006). Professional Dissertations DMin. 372. https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dmin/372 This Project Report is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Research at Digital Commons @ Andrews University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Professional Dissertations DMin by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Andrews University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ABSTRACT ELLEN WHITE’S COUNSEL TO LEADERS: IDENTIFICATION AND SYNTHESIS OF PRINCIPLES, EXPERIENTIAL APPLICATION, AND COMPARISON WITH CURRENT LEADERSHIP LITERATURE by Cynthia Ann Tutsch Adviser: Denis Fortin ABSTRACT OF GRADUATE STUDENT RESEARCH Dissertation Andrews University Seventh-day Adventist Theological Seminary Title: ELLEN WHITE’S COUNSEL TO LEADERS: IDENTIFICATION AND SYNTHESIS OF PRINCIPLES, EXPERIENTIAL APPLICATION AND COMPARISON WITH CURRENT LEADERSHIP LITERATURE’ Name of researcher: Cynthia Ann Tutsch Name and degree of faculty adviser: Denis Fortin, Ph.D. Date completed: December 2006 Ellen G. White’s counsel to leaders on both spiritual and practical themes, as well as her personal application of that counsel, has on-going relevance in the twenty-first century. The author researched secondary literature, and Ellen G. White’s published and unpublished works.