Survey Analysis for Indigenous Policy in Australia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report (2020)

For personal use only TERRACOM LIMITED 2020 ANNUAL REPORT Contents SECTION 1: COMPANY OVERVIEW 2 Chairman’s letter to shareholders 3 Directors 4 Management team 6 Company information 7 Current operations and project structure 8 Operations overview 9 Current mining tenements held 10 SECTION 2: COMPANY UPDATE 11 Operational summary 12 Production overview 13 Financial overview 14 Operational performance 15 SECTION 3: COMPANY OPERATIONS AND PROJECTS 16 Australia Operations and Projects 17 South Africa Operations and Projects 22 SECTION 4: JORC RESOURCES AND RESERVES STATEMENT 31 SECTION 5: FINANCIAL REPORT 39 Director’s Report 41 Auditors Independence Declaration 64 Statement of profit or loss 66 Statement of other comprehensive income 67 Statement of financial position 68 Corporate Directory Statement of changes in equity 70 Statement of cash flows 72 PEOPLE Notes to financial statements 77 Directors Wallace King AO Directors declaration 133 Craig Ransley Glen Lewis Independent Auditor’s Report 134 Shane Kyriakou SECTION 6: ASX ADDITIONAL SHAREHOLDER INFORMATION 141 Craig Lyons Matthew Hunter Additional shareholder information for listed public companies 142 Company Secretary Megan Etcell Chief Executive Officer Danny McCarthy Chief Commercial Officer Nathan Boom Download Chief Financial Officer Celeste van Tonder Scan the QR code to download CORPORATE INFORMATION a PDF of the 2020 TerraCom Registered Office Blair Athol Mine Access Road Limited Annual Report. Clermont, Queensland, 4721 Australia Telephone: +61 7 4983 2038 Contact Address -

Roy Hill Celebrates Historic First Shipment

10 December 2015 Roy Hill Celebrates Historic First Shipment Hancock Prospecting Pty Ltd and Roy Hill Holdings Pty Ltd are pleased to announce the historic inaugural shipment from Port Hedland of low phosphorous iron ore from the Roy Hill mine on the MV ANANGEL EXPLORER bound for POSCO’s steel mills in South Korea. Mrs Gina Rinehart, Chairman of Hancock and Roy Hill Holdings Pty Ltd, said “The Roy Hill mega project is the culmination of hard-work from the dedicated small executive and technical teams at Hancock and more recently by the entire Roy Hill team.” “Given that the mega Roy Hill Project was a largely greenfield project that carried with it significant risks and considerable cost, it is remarkable that a relatively small company such as Hancock Prospecting has been able to take on and complete a project of this sheer size and complexity.” “The Roy Hill Project has recorded many achievements already and with the first shipment it will also hold one of the fastest construction start-ups of any major greenfield resource project in Australia. This is a considerable achievement, and although the media refer to a contractors date for shipment, it remains that the shipment still occurred ahead of what the partners schedule had planned in the detailed bankable feasibility study.” “The performance on the construction gives great confidence we can achieve performance as a player of international significance in the iron ore industry. To put the scale of the Roy Hill iron ore project into perspective in regard to Australia’s economy, when the mine is operating at its full capacity, Roy Hill will generate export revenue significantly greater than either Australia's lamb and mutton export industry or our annual wine exports. -

History of Conservation Reserves in the South-West of Western Australia

JournalJournal of ofthe the Royal Royal Society Society of ofWestern Western Australia, Australia, 79(4), 79:225–240, December 1996 1996 History of conservation reserves in the south-west of Western Australia G E Rundle WA National Parks and Reserves Association, The Peninsula Community Centre, 219 Railway Parade, Maylands WA 6051 Abstract Focusing on the Darling Botanical District, reservation in the south-west of Western Australia largely involves the forest estate. The remaining natural bushland today is mainly reserves of State forest and so further opportunities to create new national parks or nature reserves of any significance would generally mean converting a State forest reserve to some other sort of conser- vation reserve. Thus, the history of Western Australia’s State forest reservation is important. The varied origins of some of the region’s well-known and popular national parks are of special interest. Their preservation as conservation reserves generally had little to do with scien- tific interest and a lot to do with community pleasure in the outdoors and scenery. Their protec- tion from early development had little to do with the flora and habitat protection needs that are the focus of these Symposium proceedings. Factors such as lack of shipping access, the discovery of glittering caverns, and the innovation of excursion railways were involved in saving the day. In contrast, the progressive reservation of State Forest was a hard slog by an insular Forests Depart- ment against many opponents. The creation of a comprehensive system of conservation reserves in this part of Western Australia is an on-going modern phenomenon with continued wide popular support. -

Case Study: Rio Tinto Iron Ore (Pilbara Iron) Centralized Monitoring Solution

Case Study: Rio Tinto Iron Ore (Pilbara Iron) Centralized Monitoring Solution of 2007, seven mines all linked by the world’s largest privately owned rail network. CHALLENGES To meet the growing demand for their iron ore, particularly from the ever-growing Chinese market, Pilbara Iron were faced with the challenge of increasing production from their mining operations, or more importantly preventing stoppages in production, while maintaining quality. It was recognized that the process control systems at their processing plants were critical assets required to be available and reliable while keeping the plant within the optimal production limits. At the same time the mining industry, like most industries, was and is facing a worldwide shortage of skilled labor to operate and maintain their plants. Rio Tinto Iron Ore Figure 1. Pilbara Iron’s operations has the added burden of very remote mining operations, making it even harder to attract and retain experienced and skilled labor, PROFILE particularly control and process engineers. The mining operations of Rio Tinto Iron Ore (Pilbara Iron) in Australia are located in the Pilbara Region, In order to offer the benefits of living in a a remote outback area in northwest Western modern thriving city, a group of process control Australia, some 1200 kilometers from Perth. Pilbara professionals was established in Perth. Iron has three export port facilities and, by the end The members of this team came from Rio Tinto A WEB-BASED SOLUTION Asset Utilization, a corporate support group To meet this need a centralized monitoring solution established within Rio Tinto at the time to address was established, with data collection performed at performance improvement across all operations the sites and analysis and diagnosis undertaken worldwide, and Pilbara Iron itself. -

Application by Robe River Mining Co Pty Ltd and Hamersley Iron Pty Ltd

AUSTRALIAN COMPETITION TRIBUNAL Applications by Robe River Mining Co Pty Ltd and Hamersley Iron Pty Ltd [2013] ACompT 2 Citation: Applications by Robe River Mining Co Pty Ltd and Hamersley Iron Pty Ltd [2013] ACompT 2 Review from: Treasurer of the Commonwealth of Australia Parties: Robe River Mining Co Pty Ltd, North Mining Ltd, Pilbara Iron Pty Ltd, Rio Tinto Ltd, Mitsui Iron Ore Development Pty Ltd, Nippon Steel Australia Pty Ltd & Sumitomo Metal Australia Pty Ltd Hamersley Iron Pty Ltd, Hamersley Iron-Yandi Pty Ltd, Robe River Mining Co Pty Ltd, North Mining Ltd, Pilbara Iron Pty Ltd, Rio Tinto Ltd, Mitsui Iron Ore Development Pty Ltd, Nippon Steel Australia Pty Ltd & Sumitomo Metal Australia Pty Ltd File numbers: ACT 3 of 2008 ACT 4 of 2008 Tribunal: MANSFIELD J (PRESIDENT) MR R SHOGREN (MEMBER) MR R STEINWALL (MEMBER) Date of judgment: 8 February 2013 Catchwords: ACCESS TO SERVICES – review of Minister’s decisions to declare two services under s 44H of Trade Practices Act 1974 (Cth) – where Minister had failed to consider proper test in applying criterion (b) in s 44H(4) – private profitability test – whether there was material which could satisfy the Tribunal about criterion (b) properly considered ACCESS TO SERVICES – review of Minister’s decisions to declare two services under s 44H of Trade Practices Act 1974 (Cth) – review being conducted after significant passage of time – extent of power of presiding member under s 44K(6) – whether in circumstances presiding member could request National Competition Council to secure experts -

Year in Review

2019 Year in Review Connecting People to Parks The WA Parks Foundation acknowledges the Traditional Owners of our national parks, conservation and nature reserves and honours the deep connection they share with country. Message from our Chair I am pleased that this year, which is the WA without network coverage Parks Foundation’s third year of operation, has using your device’s built in GPS. seen the progression of key projects to enhance I welcome and thank BHP who our Parks1 and deepen our sense of connection recently committed to sponsor to the natural environment. We have also the Smart Park Map series for three years. welcomed new partners and continued to forge strong relationships with our Founding Partners. To all our Partners, Sponsors and Donors, thank you for your A priority for the Foundation is the revitalisation plan support. Your ongoing support for Western Australia’s first national park, John Forrest. has made the work of the Working in partnership with the Parks and Wildlife Foundation possible. Service, Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and I should also mention that the State Government’s Attractions (DBCA) a business case for the development Plan for our Parks is also very exciting. The Plan will and enhancement of the park, with particular emphasis secure a further five million hectares of new national on a Visitor Centre in the Jane Brook precinct has been parks, marine parks and other conservation reserves completed, which is another step along the way towards over the next five years, seeing the conservation estate John Forrest becoming Western Australia’s Gateway increased by over 20 per cent. -

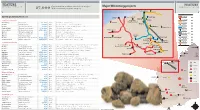

Feature Feature Major Wa Mining Projects

FEATURE FEATURE MINING OUTLOOK Construction workers needed for major Major WA mining projects MINING OUTLOOK 27,000 WA resources projects 2014-15 Source: Pitcrew Port Hedland Pardoo Rio Tinto rail MAJOR WA MINING PROJECTS Dampier Cape Lambert Iron Bridge Mt Dove Rio Tinto mine Completed in past year Balla Balla Abydos (Forge Resources) BHP rail Karara Mining Karara project $2.6bn Mid West Production ramp-up proceeding Sino Iron Wodgina Rio Tinto Hope Downs 4 mine $2.1bn Pilbara First production in H1 2013, ramping up to 15mtpa BHP mine Rio Tinto Marandoo mine expansion $1.1bn Pilbara Production will be sustained at 15mtpa for 16 further years Mt Webber McPhee Creek FMG rail Fortescue Metals Christmas Creek 2 expansion $US1.0bn Pilbara Completed in June 2013 quarter Fortescue Metals Port Hedland port expansion $US2.4bn Pilbara Fourth berth and support infrastructure opened in Aug 2013 Pannawonica FMG mine Atlas Iron Mt Dove mine development n/a Pilbara Production commenced in Dec 2012 Hancock proposed rail Atlas Iron Abydos mine development n/a Pilbara First haulage in Aug 2013, ramping up to 2-3mtpa Solomon Atlas Iron Utah Point 2 stockyard n/a Pilbara Largely complete and now ready to receive ore Hancock mine Hub Christmas Creek Rio Tinto Argyle Diamonds underground mine $US2.2bn Kimberley Production commenced in H1 2013 and is ramping up Buckland (Iron Ore Holdings) Cloudbreak Mineral Resources Sandfire Resources DeGrussa copper mine $US384m Mid West Ramp-up to nameplate production nearing completion Koodaideri Roy Hill Atlas Iron Construction -

Department of Parks and Wildlife 2014–15 Annual Report Acknowledgments

Department of Parks and Wildlife 2014–15 Annual Report Acknowledgments This report was prepared by the Public About the Department’s logo Information and Corporate Affairs Branch of the Department of Parks and Wildlife. The design is a stylised representation of a bottlebrush, or Callistemon, a group of native For more information contact: plants including some found only in Western Department of Parks and Wildlife Australia. The orange colour also references 17 Dick Perry Avenue the WA Christmas tree, or Nuytsia. Technology Park, Western Precinct Kensington Western Australia 6151 WA’s native flora supports our diverse fauna, is central to Aboriginal people’s idea of country, Locked Bag 104, Bentley Delivery Centre and attracts visitors from around the world. Western Australia 6983 The leaves have been exaggerated slightly to suggest a boomerang and ocean waves. Telephone: (08) 9219 9000 The blue background also refers to our marine Email: [email protected] parks and wildlife. The design therefore symbolises key activities of the Department The recommended reference for this of Parks and Wildlife. publication is: Department of Parks and Wildlife 2014–15 The logo was designed by the Department’s Annual Report, Department of Parks and senior graphic designer and production Wildlife, 2015 coordinator, Natalie Curtis. ISSN 2203-9198 (Print) ISSN 2203-9201 (Online) Front cover: Granite Skywalk, Porongurup National Park. September 2015 Photo – Andrew Halsall Copies of this document are available Back cover: Osprey Bay campground at night, in alternative formats on request. Cape Range National Park. Photo – Peter Nicholas/Parks and Wildlife Sturt’s desert pea, Millstream Chichester National Park. -

Park Visitor Fees for Example, Two Adults Camping at Cape Le Grand National Park for Four Open Daily 9Am to 4.15Pm

Camping fees Attraction fees Camping fees must be paid for each person for every night they stay. Please note that park passes do not apply to the following managed Entrance fees must also be paid, (if they apply) but only on the day you attractions. arrive. Parks with entrance fees are listed in this brochure. Tree Top Walk Park visitor fees For example, two adults camping at Cape Le Grand National Park for four Open daily 9am to 4.15pm. Extended hours 8am to 5.15pm from nights will pay: 26 December to 26 January. Closed Christmas Day and during hazardous conditions. 2 adults x 4 nights x $11 per adult per night plus $13 entrance = $101 • Adult $21 If you hold a park pass you only need to pay for camping. • Concession cardholder (see `Concessions´) $15.50 For information on campgrounds and camp site bookings visit • Child (aged 6 to 15 years) $10.50 parkstay.dbca.wa.gov.au. • Family (2 adults, 2 children) $52.50 Camping fees for parks and State forest No charge to walk the Ancient Empire. Without facilities or with basic facilities Geikie Gorge National Park boat trip Boat trips depart at various days and times from the end of April • Adult $8 to November. Please check departure times with the Park's and Wildlife • Concession cardholder per night (see `Concessions´) $6 Service Broome office on (08) 9195 5500. • Child per night (aged 6 to 15 years) $3 • Adult $45 With facilities such as ablutions or showers, barbeque shelters • Concession cardholder (see `Concessions´) $32 or picnic shelters • Child (aged 6 to 15 years) $12 • Adult per night $11 • Family (2 adults, 2 children) $100 • Concession cardholder per night (see `Concessions´) $7 Dryandra Woodland • Child per night (aged 6 to 15 years) $3 Fully guided night tours of Barna Mia nocturnal wildlife experience on King Leopold Ranges Conservation Park, Purnululu Mondays, Wednesdays, Fridays and Saturdays. -

Pilbara Iron Ore Project: Blacksmith Subterranean Fauna Surveys

Flinders Mines Ltd Pilbara Iron Ore Project: Blacksmith Subterranean Fauna Surveys Final Report Prepared for Flinders Mines Ltd by Bennelongia Pty Ltd December 2011 Report 2011/137 Bennelongia Pty Ltd Pilbara Iron Ore Project, Blacksmith Subterranean Fauna Surveys Pilbara Iron Ore Project: Blacksmith Subterranean Fauna Surveys Bennelongia Pty Ltd 5 Bishop Street Jolimont WA 6913 www.bennelongia.com.au ACN 124 110 167 December 2011 Report 2011/137 i Bennelongia Pty Ltd Pilbara Iron Ore Project, Blacksmith Subterranean Fauna Surveys Cover photo : Delta deposit in the Blacksmith tenement, Hamersley Range LIMITATION: This report has been prepared for use by the Client and its agents. Bennelongia accepts no liability or responsibility in respect of any use or reliance on the report by any third party. Bennelongia has not attempted to verify the accuracy and completeness of all information supplied by the Client. COPYRIGHT: The document has been prepared to the requirements of the Client. Copyright and any other Intellectual Property associated with the document belong to Bennelongia and may not be reproduced without written permission of the Client or Bennelongia. Client – Flinders Mines Ltd Report Version Prepared by Checked by Submitted to Client Method Date Draft report Vers. 1 Sue Osborne and Stuart Halse email 14.xi.2011 Michael Curran Final report Vers. 2 Sue Osborne Stuart Halse Email 14.xii.2012 K:\Projects\B_FLI_01\report\revised impact areas\report\BEC_Flinders_subfauna_Vers.2_14xii11_FINAL.docx ii Bennelongia Pty Ltd Pilbara Iron Ore Project, Blacksmith Subterranean Fauna Surveys EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Flinders Mines Limited is considering the mining of up to six iron ore deposits within the Blacksmith tenement (E47/882), approximately 60 km north-northwest of the central Pilbara town of Tom Price. -

Other Land Users

25 YEARS OF NATIVE TITLE RECOGNITION Contents Overview 1 Argyle, Western Australia 2 Burrup Ancient Art 2 Rio Tinto agreements with 3 traditional owners Facilitating engagement on 3 cultural heritage Landmark High Court 3 decision: native title rights not extinguished by Mining Leases Native title railway 4 agreement to protect rock Bendigo Mining Agreement, signed in 2000 art Historic agreement: Pilbara 4 OTHER LAND USERS traditional owners and Rio Tinto Iron Ore The introduction of the Native Title Act 1993(Cth) had a profound effect on other land users, including the resource sector, pastoralists and graziers, Agreement to protect 5 fishers and local government. For the first time there was a legal requirement Gnulli heritage to take into account the native title rights and interests of Indigenous people The development of 6 when developing land. The initial response was one of fear and uncertainty; Australian Indigenous rights however, these sectors soon adapted to the new processes and became and Rio Tinto’s Indigenous regular participants in the native title process. involvement Watch: Ms Joanne Farrell, Managing Director Australia, Rio Tinto provide a perspective from the resource sector. OTHER LAND USERS Argyle, Western Australia Rio Tinto’s Argyle mine has a Participation Agreement in place with the Traditional Owners of the Argyle land to ensure that they benefit directly from the mine’s operations, now and for generations to come. This agreement —built on the principles of co-commitment, partnership and mutual trust—encompasses land rights, income generation, employment and contracting opportunities, land management and Indigenous site protection. A Traditional Owner relationship committee meets regularly to oversee the implementation of the agreement. -

West Pilbara Iron Ore Project (WPIOP) the Largest Independent

West Pilbara Iron Ore Project (WPIOP) Project Overview and Highlights The largest independent undeveloped direct shipping iron ore project in Australia WPIOP Location Map Project Develop a competitive and profitable iron ore Vision export operation. The project is backed by two of the top five steelmakers globally, Baosteel and POSCO, Owners together with AMCI, an international resources investment and trading house, and Aurizon, a major Australian logistics company. Underpinned by ~8,000km2 tenement holding in Geology & the Western Pilbara with total Mineral Resources of ~2.7Bt of predominantly Channel Iron Deposit Resources (CID) type iron ore with current Stage 1 Mineral Resources of ~1.5Bt. Initial production target of 40Mtpa for >20 years Production of mine life with significant upside from Stage 2 deposits. Simple low cost open pit mining using excavators Mining and trucks. Conventional, predominantly dry crush and Processing screen processing at a Central Process Facility (CPF) to produce a blended fines product. New ~240km heavy haul railway to transport Rail product from the CPF to port with each train carrying over 30,000 tonnes. New multi-user deep water port at Anketell Point Port capable of handling large Cape sized (250kt) vessels, expandable to 350Mtpa of exports. West Pilbara Blend (WPB) CID fines product with a target 58.0% Fe product grade. Extensive Market sinter test work undertaken by Asian steelmakers. Feasibility study completed on 40Mtpa Stage 1 Project development. Subsequent project optimisation Status & work