The Director As Shakespeare Editor Alan C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stage by Stage South Bank: 1988 – 1996

Stage by Stage South Bank: 1988 – 1996 Stage by Stage The Development of the National Theatre from 1848 Designed by Michael Mayhew Compiled by Lyn Haill & Stephen Wood With thanks to Richard Mangan and The Mander & Mitchenson Theatre Collection, Monica Sollash and The Theatre Museum The majority of the photographs in the exhibition were commissioned by the National Theatre and are part of its archive The exhibition was funded by The Royal National Theatre Foundation Richard Eyre. Photograph by John Haynes. 1988 To mark the company’s 25th birthday in Peter Hall’s last year as Director of the National October, The Queen approves the title ‘Royal’ Theatre. He stages three late Shakespeare for the National Theatre, and attends an plays (The Tempest, The Winter’s Tale, and anniversary gala in the Olivier. Cymbeline) in the Cottesloe then in the Olivier, and leaves to start his own company in the The funds raised are to set up a National West End. Theatre Endowment Fund. Lord Rayne retires as Chairman of the Board and is succeeded ‘This building in solid concrete will be here by the Lady Soames, daughter of Winston for ever and ever, whatever successive Churchill. governments can do to muck it up. The place exists as a necessary part of the cultural scene Prince Charles, in a TV documentary on of this country.’ Peter Hall architecture, describes the National as ‘a way of building a nuclear power station in the September: Richard Eyre takes over as Director middle of London without anyone objecting’. of the National. 1989 Alan Bennett’s Single Spies, consisting of two A series of co-productions with regional short plays, contains the first representation on companies begins with Tony Harrison’s version the British stage of a living monarch, in a scene of Molière’s The Misanthrope, presented with in which Sir Anthony Blunt has a discussion Bristol Old Vic and directed by its artistic with ‘HMQ’. -

Royal Opera House Performance Review 2006/07

royal_ballet_royal_opera.qxd 18/9/07 14:15 Page 1 Royal Opera House Performance Review 2006/07 The Royal Ballet - The Royal Opera royal_ballet_royal_opera.qxd 18/9/07 14:15 Page 2 Contents 01 TH E ROYA L BA L L E T PE R F O R M A N C E S 02 TH E ROYA L OP E R A PE R F O R M A N C E S royal_ballet_royal_opera.qxd 18/9/07 14:15 Page 3 3 TH E ROYA L BA L L E T PE R F O R M A N C E S 2 0 0 6 / 2 0 0 7 01 TH E ROYA L BA L L E T PE R F O R M A N C E S royal_ballet_royal_opera.qxd 18/9/07 14:15 Page 4 4 TH E ROYA L BA L L E T PE R F O R M A N C E S 2 0 0 6 / 2 0 0 7 GI S E L L E NU M B E R O F PE R F O R M A N C E S 6 (15 matinee and evening 19, 20, 28, 29 April) AV E R A G E AT T E N D A N C E 91% CO M P O S E R Adolphe Adam, revised by Joseph Horovitz CH O R E O G R A P H E R Marius Petipa after Jean Coralli and Jules Perrot SC E N A R I O Théophile Gautier after Heinrich Meine PRO D U C T I O N Peter Wright DE S I G N S John Macfarlane OR I G I N A L LI G H T I N G Jennifer Tipton, re-created by Clare O’Donoghue STAG I N G Christopher Carr CO N D U C T O R Boris Gruzin PR I N C I PA L C A S T I N G Giselle – Leanne Benjamin (2) / Darcey Bussell (2) / Jaimie Tapper (2) Count Albrecht – Edward Watson (2) / Roberto Bolle (2) / Federico Bonelli (2) Hilarion – Bennet Gartside (2) / Thiago Soares (2) / Gary Avis (2) / Myrtha – Marianela Nuñez (1) / Lauren Cuthbertson (3) (1- replacing Zenaida Yanowsky 15/04/06) / Zenaida Yanowsky (1) / Vanessa Palmer (1) royal_ballet_royal_opera.qxd 18/9/07 14:15 Page 5 5 TH E ROYA L BA L L E T PE R F O R M A N C E S 2 0 0 6 / 2 0 0 7 LA FI L L E MA L GA R D E E NU M B E R O F PE R F O R M A N C E S 10 (21, 25, 26 April, 1, 2, 4, 5, 12, 13, 20 May 2006) AV E R A G E AT T E N D A N C E 86% CH O R E O G R A P H Y Frederick Ashton MU S I C Ferdinand Hérold, freely adapted and arranged by John Lanchbery from the 1828 version SC E N A R I O Jean Dauberval DE S I G N S Osbert Lancaster LI G H T I N G John B. -

Macbeth in World Cinema: Selected Film and Tv Adaptations

International Journal of English and Literature (IJEL) ISSN 2249-6912 Vol. 3, Issue 1, Mar 2013, 179-188 © TJPRC Pvt. Ltd. MACBETH IN WORLD CINEMA: SELECTED FILM AND TV ADAPTATIONS RITU MOHAN 1 & MAHESH KUMAR ARORA 2 1Ph.D. Scholar, Department of Management and Humanities, Sant Longowal Institute of Engineering and Technology, Longowal, Punjab, India 2Associate Professor, Department of Management and Humanities, Sant Longowal Institute of Engineering and Technology, Longowal, Punjab, India ABSTRACT In the rich history of Shakespearean translation/transcreation/appropriation in world, Macbeth occupies an important place. Macbeth has found a long and productive life on Celluloid. The themes of this Bard’s play work in almost any genre, in any decade of any generation, and will continue to find their home on stage, in film, literature, and beyond. Macbeth can well be said to be one of Shakespeare’s most performed play and has enchanted theatre personalities and film makers. Much like other Shakespearean works, it holds within itself the most valuable quality of timelessness and volatility because of which the play can be reproduced in any regional background and also in any period of time. More than the localization of plot and character, it is in the cinematic visualization of Shakespeare’s imagery that a creative coalescence of the Shakespearean, along with the ‘local’ occurs. The present paper seeks to offer some notable (it is too difficult to document and discuss all) adaptations of Macbeth . The focus would be to provide introductory information- name of the film, country, language, year of release, the director, star-cast and the critical reception of the adaptation among audiences. -

Cahiers Élisabéthains a Biannual Journal of English Renaissance Studies

Cahiers Élisabéthains A Biannual Journal of English Renaissance Studies General Editors: Yves Peyré & Charles Whitworth Revue fondée en/Founded in 1972 (ISSN 0184-7678) & publiée par/ published by L’INSTITUT DE RECHERCHES SUR LA RENAISSANCE, L’ÂGE CLASSIQUE ET LES LUMIÈRES (IRCL) UMR 5186 du CNRS, Université Paul Valéry, Route de Mende, 34199 Montpellier, France A PLAY, FILM AND OPERA REVIEW INDEX TO Cahiers Élisabéthains 1-70: CORIOLANUS (compiled by Janice Valls-Russell, Managing Editor, IRCL) Issue no. Pages Coriolanus, directed by Terry Hands for the Royal Shakespeare Company, The Aldwych Theatre, London, 9 June 1978 (Jean VACHÉ) 14 111-12 Coriolanus, directed by Terry Hands for the Royal Shakespeare Company, Théâtre National de l’Odéon, Paris, 3-8 April 1979 (Frédéric FERNEY) 16 97-99 Coriolanus, directed by Brian Bedford for the Stratford Shakespeare Festival, Stratford, Ontario, 16 June 1981 (Charles HAINES) 20 119-20 Coriolan, directed by Bernard Sobel, Théâtre de Gennevilliers, 3 March 1983 (Leonore LIEBLEIN) 24 96-97 Coriolanus, produced by Shaun Sutton and directed by Elijah Moshinsky, BBC Shakespeare, BBC 2, 21 April 1984 (G. M. PEARCE) 26 96-98 The Roman Tragedies. 60 mn video cassette, based on Julius Caesar, Antony and Cleopatra, and Coriolanus. Written and presented by David Whitworth, produced and directed by Noël Hardy (G. M. PEARCE) 28 87-88 Coriolanus, directed by Peter Hall, National Theatre, London, 8 May 1985 (G. M. PEARCE) 28 93-95 Coriolanus, directed by Jane Howell, The Young Vic, London, 27 May 1989 (Peter J. SMITH) 36 97-98 Coriolanus, directed by Terry Hands for the Royal Shakespeare Company, Barbican Main Theatre, London, 2 May 1990 (Jill PEARCE) 38 95-96 Coriolanus, directed by Michael Bogdanov for the English Shakespeare Company, Theatre Royal, Nottingham, 12 December 1990 (Peter J. -

La-Boheme-Extract.Pdf

OVERTURE OPERA GUIDES in association with We are delighted to have the opportunity to work with Overture Publishing on this series of opera guides and to build on the work English National Opera did over twenty years ago with the Calder Opera Guide Series. As well as reworking and updating existing titles, Overture and ENO have commissioned new titles for the series and all of the guides will be published to coincide with the repertory being staged by the company. We hope that these guides will prove an invaluable resource now and for years to come, and that by delving deeper into the history of an opera, the libretto and the nuances of the score, readers’ understanding and appreciation of the opera and the art form in general will be enhanced. Daniel Kramer Artistic Director, ENO The publisher John Calder began the Opera Guides series under the editorship of the late Nicholas John in associa- tion with English National Opera in 1980. It ran until 1994 and eventually included forty-eight titles, covering fifty-eight operas. The books in the series were intended to be companions to the works that make up the core of the operatic repertory. They contained articles, illustrations, musical examples and a complete libretto and singing translation of each opera in the series, as well as bibliographies and discographies. The aim of the present relaunched series is to make available again the guides already published in a redesigned format with new illustrations, revised and newly commissioned articles, up- dated reference sections and a literal translation of the libretto that will enable the reader to get closer to the meaning of the original. -

Overture Opera Guides

overture opera guides in association with We are delighted to have the opportunity to work with Overture Publishing on this series of opera guides and to build on the work English National Opera did over twenty years ago on the Calder Opera Guide Series. As well as reworking and updating existing titles, Overture and ENO have commissioned new titles for the series and all of the guides will be published to coincide with repertoire being staged by the company at the London Coliseum. We hope that these guides will prove an invaluable resource now and for years to come, and that by delving deeper into the history of an opera, the poetry of the libretto and the nuances of the score, read- ers’ understanding and appreciation of the opera and the art form in general will be enhanced. John Berry Artistic Director, ENO The publisher John Calder began the Opera Guides series under the editorship of the late Nicholas John in association with English National Opera in 1980. It ran until 1994 and eventu- ally included forty-eight titles, covering fifty-eight operas. The books in the series were intended to be companions to the works that make up the core of the operatic repertory. They contained articles, illustrations, musical examples and a complete libretto and singing translation of each opera in the series, as well as bibliographies and discographies. The aim of the present relaunched series is to make available again the guides already published in a redesigned format with new illustrations, some newly commissioned articles, updated reference sections and a literal translation of the libretto that will enable the reader to get closer to the intentions and meaning of the original. -

Bernard Lloyd

Paddock Suite, The Courtyard, 55 Charterhouse Street, London, EC1M 6HA p: + 44 (0) 20 73360351 e: [email protected] Phone: + 44 (0) 20 73360351 Email: [email protected] Bernard Lloyd Location: London Appearance: White Height: 5'9" (175cm) Other: Equity Weight: 12st. 2lb. (77kg) Eye Colour: Brown Playing Age: Over 70 years Hair Colour: Grey Stage 2015, Stage, Arnold, Now Is Not The End, Arcola Theatre, Katie Lewis 2014, Stage, Cardinal Ottaviani, The Last Confession, Trimumph Entertainment / World Tour, Jonathan Church 2011, Stage, Duke of Gloucester, King Lear, West Yorkshire Playhouse, Ian Brown 2007, Stage, Villot, The Last Confession, Theatre Royal Haymarket, David Jones 2006, Stage, Vincent Crummles, Nicholas Nickleby, Chichester Festival Theatre, Jonathan Church & Philip Franks 2006, Stage, Harry Morrison, Bishop of Putney, Pravda, Chichester Festival Theatre & Birmingham Rep, Jonathan Church 2001, Stage, Johnson Over Jordan, West Yorkshire Playhouse, Jude Kelly 2000, Stage, Chas, Still Time, Manchester Royal Exchange, Sarah Frankcom 1998, Stage, Tom Connolly, Give Me Your Answer Do, Lyric Theatre Belfast, Ben Twist 1998, Stage, Chaplain, Mother Courage, Manchester Contact Theatre, Ben Twist 1997, Stage, Quince, A Midsummer Night's Dream, Royal Shakespeare Company, Adrian Noble 1996, Stage, Sir Toby Belch, Twelfth Night, Royal Shakespeare Company, Ian Judge 1995, Stage, Aunt Augusta, Travels With My Aunt, York Theatre Royal, John Doyle 1994, Stage, Don Fernando, Le Cid, Royal National Theatre, Jonathan Kent Stage, Marley's Ghost, A -

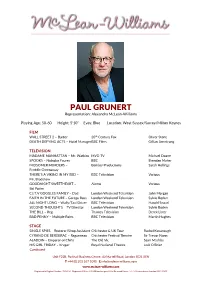

PAUL GRUNERT Representation: Alexandra Mclean-Williams

PAUL GRUNERT Representation: Alexandra McLean-Williams Playing Age: 50-60 Height: 5’10” Eyes: Blue Location: West Sussex/Surrey/Milton Keynes FILM WALL STREET 2 – Barber 20th Century Fox Oliver Stone DEATH DEFYING ACTS – Hotel Manager BBC Films Gillian Armstrong TELEVISION MADAME MANHATTAN – Mr. Watkins MVD TV Michael Doane SPOOKS – Nicholas Faures BBC Brendan Maher MIDSOMER MURDERS – Bentley Productions Sarah Hellings Freddie Greenaway THERE’S A VIKING IN MY BED – BBC Television Various Mr. Bradshaw GOODNIGHT SWEETHEART – Alamo Various Sid Potter C.I.T.V GOGGLES FAMILY – Dad London Weekend Television John Morgan FAITH IN THE FUTURE – Garage Boss London Weekend Television Sylvie Boden ALL NIGHT LONG – Wally/Taxi Driver BBC Television Harold Snoad SECOND THOUGHTS – TV Director London Weekend Television Sylvie Boden THE BILL – Reg Thames Television Derek Lister BAD PENNY – Multiple Roles BBC Television Martin Hughes STAGE SINGLE SPIES – Restorer/Shop Assistant Chichester & UK Tour Rachel Kavanaugh CYRANO DE BERGERAC – Ragueneau Chichester Festival Theatre Sir Trevor Nunn ALADDIN – Emperor of China The Old Vic Sean Mathias HIS GIRL FRIDAY – Kruger Royal National Theatre Jack O’Brian Continued Unit F22B, Parkhall Business Centre, 40 Martell Road, London SE21 8EN T +44 (0) 203 567 1090 E [email protected] www.mclean-williams.com Registered in England Number: 7432186 Registered Office: C/O William Sturgess & Co, Burwood House, 14 - 16 Caxton Street, London SW1H 0QY PAUL GRUNERT continued LOVE’S LABOUR’S LOST – Sir Nathaniel Royal National -

Players of Shakespeare

POSA01 08/11/1998 10:09 AM Page i Players of Shakespeare This is the fourth volume of essays by actors with the Royal Shake- speare Company. Twelve actors describe the Shakespearian roles they played in productions between and . The contrib- utors are Christopher Luscombe, David Tennant, Michael Siberry, Richard McCabe, David Troughton, Susan Brown, Paul Jesson, Jane Lapotaire, Philip Voss, Julian Glover, John Nettles, and Derek Jacobi. The plays covered include The Merchant of Venice, Love’s Labour’s Lost, The Taming of the Shrew, The Winter’s Tale, Romeo and Juliet, and Macbeth, among others. The essays divide equally among comedies, histories and tragedies, with emphasis among the comed- ies on those notoriously difficult ‘clown’ roles. A brief biographical note is provided for each of the contributors and an introduction places the essays in the context of the Stratford and London stages. POSA01 08/11/1998 10:09 AM Page ii POSA01 08/11/1998 10:09 AM Page iii Players of Shakespeare Further essays in Shakespearian performance by players with the Royal Shakespeare Company Edited by Robert Smallwood POSA01 08/11/1998 10:09 AM Page iv The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge , United Kingdom The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge , United Kingdom West th Street, New York, –, USA Stamford Road, Oakleigh, Melbourne , Australia © Cambridge University Press, This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published Printed in the United Kingdom at the University Press, Cambridge Typeset in ./pt Plantin Regular A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress cataloguing in publication data Players of Shakespeare : further essays in Shakespearian performance /by players with the Royal Shakespeare Company; edited by Robert Smallwood. -

Introduction: Theatre, Space, and World-Making

Notes Introduction: Theatre, Space, and World-making 1. This work is primarily focused on theatre studies but its argument also pertains to the broader field of performance studies. 2. For a fuller discussion of this text, the significance of land rights, the importance of simultaneous occupation, and the staging of landscape in Australia, see my Unsettling Space (2006, pp. 25–48). 3. Escolme describes the ways in which a similar design decision was used in a Royal Shakespeare Company production of Richard II with Sam West, directed by Steven Pimlott at The Other Place in 2000. Her interpretation of this moment takes the argument about the externalities in a different direction – she explores the ‘violence done to conventions of inside and outside’ (2006, p. 107) – but she recognizes this staging technique as a challenge to space, reality, and as a result, the politics of the play itself. A movie that mirrors this approach is Tim Robbins’s 1999 Cradle Will Rock about the actual 1937 attempt to mount Marc Blitzstein’s left-leaning musical of the same name. It depicts the power of theatre in the United States where the hunt for Communists among artistic communities destroyed lives and careers. Thanks to Fred D’Agostino for alerting me to this film. 4. Barker’s argument may appear to be utopian rather than heterotopic but as I argue in Chapter 1, there are intersections between these terms. While heterotopia also has a utopian aspect, I regard it as more likely to be materialized than utopia. 5. Of course, analysing performance necessarily calls on a broad range of theatrical features. -

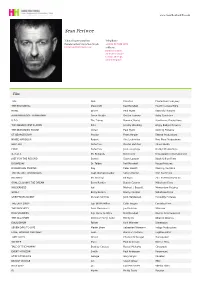

Sean Pertwee

www.hamiltonhodell.co.uk Sean Pertwee Talent Representation Telephone Madeleine Dewhirst & Sian Smyth +44 (0) 20 7636 1221 [email protected] Address Hamilton Hodell, 20 Golden Square London, W1F 9JL, United Kingdom Film Title Role Director Production Company THE RECKONING Moorcroft Neil Marshall Fourth Culture Films HOWL Driver Paul Hyett Starchild Pictures ALAN PARTRIDGE: ALPHA PAPA Steve Stubbs Declan Lowney Baby Cow Films U.F.O. The Tramp Dominic Burns Hawthorne Productions THE MAGNIFICENT ELEVEN Pete Jeremy Wooding Angry Badger Pictures THE SEASONING HOUSE Goran Paul Hyett Sterling Pictures ST GEORGE'S DAY Proctor Frank Harper Elstree Productions NAKED HARBOUR Robert Aku Louhimies First Floor Productions WILD BILL Detective Dexter Fletcher 20Ten Media FOUR Detective John Langridge Oh My! Productions 4, 3, 2, 1 Mr. Richards Noel Clark Unstoppable Entertainment JUST FOR THE RECORD Sensei Steve Lawson Black & Blue Films DOOMSDAY Dr. Talbot Neil Marshall Rogue Pictures DANGEROUS PARKING Ray Peter Howitt Flaming Pie Films THE MUTANT CHRONICLES Capt. Nathan Rooker Simon Hunter First Foot Films BOTCHED Mr. Groznyi Kit Ryan Zinc Entertainment Inc. GOAL! 2: LIVING THE DREAM Barry Rankin Danny Cannon Milkshake Films WILDERNESS Jed Michael J. Bassett Momentum Pictures GOAL! Barry Rankin Danny Cannon Milkshake Films GREYFRIARS BOBBY Duncan Smithie John Henderson Piccadilly Pictures THE LAST DROP Sgt. Bill McMillan Colin Teague Carnaby Films THE PROPHECY Dani Simionescu Joel Soisson Miramax DOG SOLDIERS Sgt. Harry G. Wells Neil Marshall Kismet Entertainment THE 51st STATE Detective Virgil Kane Ronny Yu Alliance Atlantis EQUILIBRIUM Father Kurt Wimmer Dimension SEVEN DAYS TO LIVE Martin Shaw Sebastian Niemann Indigo Productions LOVE, HONOUR AND OBEY Sean Dominic Anciano Fugitive Films TUBE TALES Driver Charles McDougal Horsepower SOLDIER Mace Paul Anderson Warner Bros. -

Genesis IV Summer 2004 Edition

GENESIS IV THE ALUMNI MAGAZINE OF SAINT IGNATIUS COLLEGE PREPARATORY, SAN FRANCISCO, SUMMER 2004 2 Development News A Legacy for a father from Chronicle reporter John Wildermuth ’69 • SI thanks parents who have completed their pledge to support the school. 7 Feature Articles The Buddy System: Tom Leach ’94 & Bill Duggan ’93 are the success behind TV’s Curb Appeal • Mike Nevin ’61 & Ed McGovern ’75 are among the top COVER STORY: The Class of 2004 received 10 most infl uential in San Mateo County • Physics teachers Byron Philhour their diplomas … Page 18. & James Dann ask students to look at the sky and wonder • Celine Alwyn ’98 & Brendan Quigley ’78 are in and behind the spotlights on Broadway. 18 School News COVER STORY: Class of 2004 honored at 145th commencement ceremonies • Valedictorian Kevin Feeney asks students to heed the prophets • St. Antho- ny’s Fr. John Hardin receives President’s Award • Chad Evans bikes across the US to raise awareness for poverty. SPORTS: The Boys’ Varsity 8 took third in the nation in crew … Page 31. 32 Alumni News All-Alumni Sports Day brings 400 graduates back to SI • Actor, Producer, Director Geoff Callan ’85 does it all • Sean Cheetham ’95 fi nds faith through art • Looking back 15 years on coeducation. 42 Sports Highlights Boys’ Varsity Crew takes third in nation • Alumni lacrosse players win na- tional championship 45 Departments Keeping in Touch • Births • In Memoriam • Feedback • Calendar On the cover: The Class of 2004 celebrates outside St. Ignatius Church mo- ments after they received their diplomas. Photo by Paul Totah.