The Tafelmusik of Don Giovanni

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Pomegranate Cycle

The Pomegranate Cycle: Reconfiguring opera through performance, technology & composition By Eve Elizabeth Klein Bachelor of Arts Honours (Music), Macquarie University, Sydney A PhD Submission for the Department of Music and Sound Faculty of Creative Industries Queensland University of Technology Brisbane, Australia 2011 ______________ Keywords Music. Opera. Women. Feminism. Composition. Technology. Sound Recording. Music Technology. Voice. Opera Singing. Vocal Pedagogy. The Pomegranate Cycle. Postmodernism. Classical Music. Musical Works. Virtual Orchestras. Persephone. Demeter. The Rape of Persephone. Nineteenth Century Music. Musical Canons. Repertory Opera. Opera & Violence. Opera & Rape. Opera & Death. Operatic Narratives. Postclassical Music. Electronica Opera. Popular Music & Opera. Experimental Opera. Feminist Musicology. Women & Composition. Contemporary Opera. Multimedia Opera. DIY. DIY & Music. DIY & Opera. Author’s Note Part of Chapter 7 has been previously published in: Klein, E., 2010. "Self-made CD: Texture and Narrative in Small-Run DIY CD Production". In Ø. Vågnes & A. Grønstad, eds. Coverscaping: Discovering Album Aesthetics. Museum Tusculanum Press. 2 Abstract The Pomegranate Cycle is a practice-led enquiry consisting of a creative work and an exegesis. This project investigates the potential of self-directed, technologically mediated composition as a means of reconfiguring gender stereotypes within the operatic tradition. This practice confronts two primary stereotypes: the positioning of female performing bodies within narratives of violence and the absence of women from authorial roles that construct and regulate the operatic tradition. The Pomegranate Cycle redresses these stereotypes by presenting a new narrative trajectory of healing for its central character, and by placing the singer inside the role of composer and producer. During the twentieth and early twenty-first century, operatic and classical music institutions have resisted incorporating works of living composers into their repertory. -

Vicente Martín Y Soler 1754?-1806

2 SEMBLANZAS DE COMPOSITORES ESPAÑOLES 11 VICENTE MARTÍN Y SOLER 1754?-1806 Leonardo J. Waisman Investigador del Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas, Argentina n los años alrededor de 1790, el compositor más querido por el gran público euro- E peo era un español. Aunque Haydn, Mozart y Beethoven estaban vivos y en plena producción, el predilecto de la mayoría de los oyentes era el valenciano Vicente Martín y Soler. Esto se verificaba especialmente en la ciudad en que tanto Vicente como los tres grandes maestros del clasicismo residían: Viena, pero también era cierto en los grandes centros operísticos de Italia, Inglaterra, Alemania y Francia. En España misma, quizás el público en general no compartiera esa predilección, pero la familia real elegía reiterada- mente sus óperas para celebrar acontecimientos festivos. Aunque Martín y Soler cultivó muchos de los géneros vocales en boga durante la segun- da mitad del siglo XVIII (ópera seria, oratorio, opéra comique, opera komicheskaya rusa, cantata, serenata, canción) y cosechó muchos aplausos por sus numerosas composicio- nes para ballet, fue sin duda a través de la ópera bufa en italiano como conquistó el co- razón de los melómanos de todo el continente. En particular, tres de ellas tuvieron un éxi- to tal como para generar modas en el vestir y expresiones idiomáticas que entraron en el En «Semblanzas de compositores españoles» un especialista en musicología expone el perfil biográfico y artístico de un autor relevante en la historia de la música en España y analiza el contexto musical, social y cultural en el que desarrolló su obra. -

PPO2 Schneider 2.Pages

Performing Premodernity Online – Volume 2 (January 2015) On Acting in Late Eighteenth- Century Opera Buffa MAGNUS TESSING SCHNEIDER In 1856 the German poet and music critic Johann Peter Lyser wrote about the beginning of the supper scene in the second finale of Don Giovanni, written for the comedians Luigi Bassi and Felice Ponziani: "Unfortunately, it is not performed in Mozart's spirit nowadays, for the Don Giovannis and Leporellos of today are no Bassis and Lollis [recte: Ponzianis]. These played the scene differently in each performance, sustaining an uninterrupted crossfire of improvised jokes, droll ideas and lazzi, so that the audience was thrown into the same state of mirth in which it was Mozart's intention that master and servant should appear to be on the stage. These were the skills of the opera buffa singers of old; the modern Italian singers know as little how to do it as the Germans ever did."1 Though written more than 150 years ago, this longing for the musical and theatrical immediacy that reigned in the opera houses of the late eighteenth century may still resonate with adherents of the Historically Informed Performance (HIP) movement. At least since Georg Fuchs coined the motto "rethéâtraliser le théâtre" in 19092 the theatrical practices of the past has, indeed, been an important source of inspiration for theatrical reformers, and the commedia dell'arte, with its reliance on virtuoso improvisation rather than on written text, has appealed to many directors. Yet as the Lyser quotation suggests, the idealization of a lost tradition as the positive counter- image of the restrictions of the modern stage is not a new phenomenon. -

The Extraordinary Lives of Lorenzo Da Ponte & Nathaniel Wallich

C O N N E C T I N G P E O P L E , P L A C E S , A N D I D E A S : S T O R Y B Y S T O R Y J ULY 2 0 1 3 ABOUT WRR CONTRIBUTORS MISSION SPONSORSHIP MEDIA KIT CONTACT DONATE Search Join our mailing list and receive Email Print More WRR Monthly. Wild River Consulting ESSAY-The Extraordinary Lives of Lorenzo Da Ponte & Nathaniel & Wallich : Publishing Click below to make a tax- deductible contribution. Religious Identity in the Age of Enlightenment where Your literary b y J u d i t h M . T a y l o r , J u l e s J a n i c k success is our bottom line. PEOPLE "By the time the Interv iews wise woman has found a bridge, Columns the crazy woman has crossed the Blogs water." PLACES Princeton The United States The World Open Borders Lorenzo Da Ponte Nathaniel Wallich ANATOLIAN IDEAS DAYS & NIGHTS Being Jewish in a Christian world has always been fraught with difficulties. The oppression of the published by Art, Photography and Wild River Books Architecture Jews in Europe for most of the last two millennia was sanctioned by law and without redress. Valued less than cattle, herded into small enclosed districts, restricted from owning land or entering any Health, Culture and Food profession, and subject to random violence and expulsion at any time, the majority of Jews lived a History , Religion and Reserve Your harsh life.1 The Nazis used this ancient technique of de-humanization and humiliation before they hit Philosophy Wild River Ad on the idea of expunging the Jews altogether. -

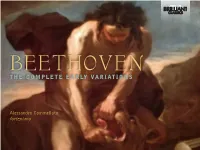

The Complete Early Variations

BEETHOVEN THE COMPLETE EARLY VARIATIONS Alessandro Commellato fortepiano Ludwig van Beethoven 1770-1827 1. 32 Variations in C minor 8. 10 Variation in B flat WoO73 14. 8 Variations in C WoO67 WoO80 on an original theme 11’43 on Salieri’s air ‘La stessa on a theme by Count Waldstein 2. 5 Variations in D WoO79 la stessissima’ 12’28 for piano four hands 8’58 on ‘Rule Britannia’ 5’36 9. 8 Variations in C WoO72 on 15. 13 Variations in A WoO66 3. 7 Variations in D WoO78 Grétry’s air ‘Un fievre brûlante’ 7’12 on Dittersdorf’s air ‘Es war on ‘God save the King’ 8’43 10. 12 Variations in A WoO71 on a einmal ein alter Mann’ 14’55 4. 6 Easy Variations in G WoO77 Russian Dance from Wranitsky’s 16. 24 Variations in D WoO65 on an original theme 7’27 ballet ‘Das Waldmädchen’ 12’20 on Righini’s air ‘Venni amore’ 23’29 5. 8 Variations in F WoO76 11. 6 Variations in G WoO70 17. 6 Easy Variations in F WoO64 from Süssmayr’s theme on Paisiello's air on a Swiss air 2’57 ‘Tändeln und Scherzen’ 9’21 ‘Nel cor più non mi sento’ 5’45 18. 9 Variations in C minor WoO63 6. 7 Variations in F WoO75 12. 9 Variations in A WoO69 on on a march by Dressler 12’41 from Winter’s opera ‘Das Paisiello’s air ‘Quant’è più bello’ 6’07 unterbrochene Opferfest’ 11’54 13. 12 Variations in C WoO68 Alessandro Commellato fortepiano 7. -

The Cleveland Opera: Don Giovanni at First Baptist Church (April 8)

The Cleveland Opera: Don Giovanni at First Baptist Church (April 8) by Robert Rollin On Saturday night, April 8, The Cleveland Opera gave an outstanding performance of Mozart’s Don Giovanni at First Baptist Church in Shaker Heights. Despite the venue’s awkward acoustics and lack of a pit for the sizeable orchestra, conductor Grzegorz Nowak led a well-balanced performance that allowed the singers to be heard clearly. The opera flowed beautifully through its many intricate arias, recitatives, and ensembles, and all eight leads were in fine voice. Baritone Lawson Alexander was terrific as Don Giovanni. His powerful, darkly-hued voice brought the character’s callous licentiousness to life. Pacing was excellent during the famous duet “Là ci darem la mano,” when Don Giovanni attempts to seduce the peasant girl Zerlina. Bass Nathan Baer was outstanding as the servant Leporello, especially during the “Catalogue Aria,” when he lists the womanizing title character’s many “conquests” by country. Baer possesses a magnificent voice, although at times it was difficult to hear him over the thick accompaniment. Soprano Dorota Sobieska sparkled as Donna Anna. Her light soprano floated beautifully in the highest range. She and her love interest Don Ottavio (sung by tenor Kyle Kelvington) skillfully negotiated their virtuosic coloratura passages. Rachel Morrison, as Donna Elvira, sang with a gorgeous full tone, as did fellow soprano Susan Fletcher, as Zerlina, while bass Christopher Aldrich depicted Masetto’s peasant background with fine vocal color and strong delivery. Bass Adam E. Shimko, as the Commendatore, was vocally solid but lacked the dark timbre needed for the character. -

Frances Stark's the Magic Flute

FRANCES STARK’S THE MAGIC FLUTE (ORCHESTRATED BY DANKO DRUSKO) A PEDAGOGICAL OPERA - CONDUCTOR AS COLLABORATOR by Danko Drusko Submitted to the faculty of the Jacobs School of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree, Doctor of Music Indiana University December 2018 Accepted by the faculty of the Indiana University Jacobs School of Music, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Music Doctoral Committee ______________________________________ Arthur Fagen, Research Director & Chair ______________________________________ Gary Arvin ______________________________________ Betsy Burleigh ______________________________________ Walter Huff November 30, 2018 ii Copyright © 2018 Danko Drusko iii To my mother, who has always been my greatest role model, supporter, and inspiration in mastering life. To my father, who died 22 years ago, and with whom I wish I had just spent a little more time. I will always remember you. To Ameena, who supported me throughout this process. iv Acknowledgements I would like to express the deepest appreciation to my committee research director, Professor and Maestro Arthur Fagen, who has given me the opportunity to study under him and learn his craft. He continually supported my endeavors and spirit of adventure in regard to repertoire and future projects, as well as inspired in me an excitement for teaching. Without his guidance throughout the years this dissertation would not have been possible. I would like to thank my committee members, Professor Betsy Burleigh and Professor Walter Huff, whose professional and human approach to music-making demonstrated to me that working in this field is more than merely fixing notes and also involves our spirit. -

A Performance Edition of the Opera Kaspar Der Fagottist by Wenzel Müller

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2003 A performance edition of the opera Kaspar der Fagottist by Wenzel Müller (1767-1835), as arranged for Harmonie by Georg Druschetzky (1745-1819) Susan Nita Barber Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Barber, Susan Nita, "A performance edition of the opera Kaspar der Fagottist by Wenzel Müller (1767-1835), as arranged for Harmonie by Georg Druschetzky (1745-1819)" (2003). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 2272. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/2272 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. A PERFORMANCE EDITION OF THE OPERA, KASPAR DER FAGOTTIST BY WENZEL MÜLLER (1767-1835), AS ARRANGED FOR HARMONIE BY GEORG DRUSCHETZKY (1745-1819) Written Document Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in The College of Music and Dramatic Arts By Susan Nita Barber B.M., State University of New York at Potsdam, 1988 M.M., The Juilliard School, 1990 May 2003 „ Copyright 2002 Susan N. Barber All rights reserved ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to express my thanks to my husband, family, friends and colleagues for their support throughout the time that I have been engaged in my research and writing for this degree. -

DOROTHEA LINK Professor of Musicology Distinguished

DOROTHEA LINK Professor of Musicology Distinguished Research Professor Hugh Hodgson School of Music, 250 River Rd., University of Georgia, Athens, GA 30602 tel: 706 542 1034; fax: 706 542 2773; email: dlink AT uga.edu PUBLICATIONS Authored Books Arias for Stefano Mandini, Mozart’s first Count Almaviva. Recent Researches in the Music of the Classical Era 97. Middleton, WI: A-R Editions, 2015 (xlv, 127 pages). Reviews: Magnus Tessing Schneider in Notes: Quarterly Journal of the Music Library Association 73 (December 2016): 339-45. Arias for Vincenzo Calvesi, Mozart’s first Ferrando. Recent Researches in the Music of the Classical Era 84. Middleton, WI: A-R Editions, 2011 (xxxv, 118 pages). Reviews: Clifford Bartlett in Early Music Review 146 (February 2012): 6-7; Joshua Neumann in Notes: Quarterly Journal of the Music Library Association 70 (December 2013): 321-5. Arias for Francesco Benucci, Mozart's first Figaro and Guglielmo. Recent Researches in the Music of the Classical Era 72. Middleton, WI: A-R Editions, 2004 (xxvii, 120 pages). Reviews: Laurel E. Zeiss in Newsletter of the Society for Eighteenth-Century Music 7 (October 2005): 5-7; Julian Rushton in Early Music 36 (August 2008): 474-6; Saverio Lamacchia in Il saggiotore musicale 15, no. 2 (2008): 359-62. Arias for Nancy Storace, Mozart's first Susanna. Recent Researches in the Music of the Classical Era 66. Middleton, WI: A-R Editions, 2002 (xxv, 122 pages). Reviews: Emma Kirkby in Early Music (May 2003): 297-298; Constance Mayer in Notes: Quarterly Journal of the Music Library Association 60 (June 2004), 1032-1034; Julian Rushton in Music & Letters 85 (November 2004): 682-683; Laurel E. -

Don Giovanni

NATIONAL CAPITAL OPERA SOCIETY • SOCIÉTÉ D'OPÉRA DE LA CAPITALE NATIONALE Newsletter • Bulletin Spring 2012 www.ncos.ca Printemps 2012 P.O. Box 8347, Main Terminal, Ottawa, Ontario K1G 3H8 • C.P. 8347, Succursale principale, Ottawa (Ontario) K1G 3H8 Unlucky Valentines by Shelagh Williams The February offerings of Toronto’s Canadian Opera concept allowed events to unfold naturally, although the Company (COC) featured stories of thwarted love com- second act could have been more tense and scary: this posed a century apart: Puccini’s Tosca (1900) and Kaija Scarpia did not seem as evil and lecherous as some I’ve Saariaho’s Love From Afar (2000)! seen, nor were Cavaradossi’s screams under torture as It is a pleasure to report that the Tosca was an loud and spine-chilling as they could have been. Veteran opulent production, setting forth the story in a clear, straight Canadian bass-baritone Peter Strummer knew just how forward manner, and featuring an excellent cast - a rare to evoke the humour of the Sacristan, although at times he set of claims for many operas these days! It was a re- seemed a bit too broad and irreligious in his actions. We mount of the COC’s own lovely 2008 production (which have seen American baritone Mark Delavan, here debut- I did not see) by the creative team of Scottish director ing at the COC as Scarpia, in his early days at Paul Curran, set and costume de- Glimmerglass Opera, and it is pleas- signer Kevin Knight and lighting de- Tosca ing to find that he has developed so signer David Martin Jacques. -

Don Juan Study Guide

Don Juan Study Guide © 2017 eNotes.com, Inc. or its Licensors. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. No part of this work covered by the copyright hereon may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping, Web distribution or information storage retrieval systems without the written permission of the publisher. Summary Don Juan is a unique approach to the already popular legend of the philandering womanizer immortalized in literary and operatic works. Byron’s Don Juan, the name comically anglicized to rhyme with “new one” and “true one,” is a passive character, in many ways a victim of predatory women, and more of a picaresque hero in his unwitting roguishness. Not only is he not the seductive, ruthless Don Juan of legend, he is also not a Byronic hero. That role falls more to the narrator of the comic epic, the two characters being more clearly distinguished than in Byron’s Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage. In Beppo: A Venetian Story, Byron discovered the appropriateness of ottava rima to his own particular style and literary needs. This Italian stanzaic form had been exploited in the burlesque tales of Luigi Pulci, Francesco Berni, and Giovanni Battista Casti, but it was John Hookham Frere’s (1817-1818) that revealed to Byron the seriocomic potential for this flexible form in the satirical piece he was planning. The colloquial, conversational style of ottava rima worked well with both the narrative line of Byron’s mock epic and the serious digressions in which Byron rails against tyranny, hypocrisy, cant, sexual repression, and literary mercenaries. -

Sarti's Fra I Due Litiganti and Opera in Vienna

John Platoff Trinity College March 18 2019 Sarti’s Fra i due litiganti and Opera in Vienna NOTE: This is work in progress. Please do not cite or quote it outside the seminar without my permission. In June 1784, Giuseppe Sarti passed through Vienna on his way from Milan to St. Petersburg, where he would succeed Giovanni Paisiello as director of the imperial chapel for Catherine the Great. On June 2 Sarti attended a performance at the Burgtheater of his opera buffa Fra i due litiganti il terzo gode, which was well on its way to becoming one of the most highly successful operas of the late eighteenth century. At the order of Emperor Joseph II, Sarti received the proceeds of the evening’s performance, which amounted to the substantial sum of 490 florins.1 Fra i due litiganti, premiered at La Scala in Milan on September 14, 1782, had been an immediate success, and within a short time began receiving productions in other cities. It was performed in Venice under the title I pretendenti delusi; and it was the third opera produced in Vienna by the newly re-established opera buffa company there in the spring of 1783. By the time of Sarti’s visit to the Hapsburg capital a year later, Fra i due litiganti was the most popular opera in Vienna. It had already been performed twenty-eight times in its first season alone, a total unmatched by any other operatic work of the decade. Thus the Emperor’s awarding 1 Link, National Court Theatre, 42 and n.