Open Thesis-Alireza Arabshahi.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Football Cover Single FINAL.Jpg

TABLE OF CONTENTS GENERAL INFORMATION • 2-7 HISTORY • 95-123 President Morton Schapiro ...................2 Yearly Summary ....................................96 Year-By-Year Results ................... 97-102 Vice President for Letterwinners ................................103-110 Athletics & Recreation Wildcat Legend Otto Graham ............111 Jim Phillips ............................................. 3-7 All-Americans/All-Big Ten ...........112-113 Academic All-Big Ten ................... 114-116 NU Most Valuable Players ..................115 Northwestern Team Awards.............. 117 College Football Hall of Fame ..........118 All-Star Game Participants ................119 Wildcats in the Pros .....................120-121 Wildcat Professional Draftees ....... 122-123 2015 TEAM BACKGROUND RECORD BOOK • 124-145 INFORMATION • 8-17 Total Oense .........................................126 Season Notes .....................................10-11 Rushing ........................................... 127-128 Personnel Breakdown .....................12-13 Passing .............................................129-131 Rosters .................................................14-15 Receiving ........................................ 132-133 2015 Quick Facts/Schedule ................16 All-Purpose Yards ........................133-134 All-Time Series Records ........................17 Punt Returns .........................................135 Kicko Returns .....................................136 Punting .................................................. -

Building Renovations, Memorial to Be Completed Roughly on Time

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ Reviews - page 8-9 I • VOL. XX, NO. 137 THURSDAY, MAY 1, 1986 - · an independent student newspaper serving Notre Dame and Saint Mary's Mayor calls for increased patrols to monitor conduct of partygoers By FRANK LIPO tygoers), but if we have to we will," South Bend city attorney Executive News Editor he said. Eugenia Schwartz, who was also at Uniformed officers on foot the press conference, said that "int The South Bend Police Depart patrols, uniformed officers in the past we've had complete com ment has increased police patrols in police cars and undercover pliance when noise citations have the Northeast Neighborhood, in a plainclothes officers will be used to been issued." move designed to control a wave enforce city noise regulations and "We haven't had that kind of of recent student parties which to monitor the conduct of par response and respectful attitude have disturbed area residents, ac tygoers, according to Captain from the folks who have been cordiug to South Bend Mayor Patrick Cottrell, head of the South issued the citations this year," she Roger Parent. Bend Police Department's East Sec said. The increased patrols come in the tor, who was also in attendance at Schwartz said there were parties wake of complaints by area the press conference. broken up at six different addresses residents against the noise level Parties will be monitored with last weekend, each with more than generated by the parties this spring noise meters, said Cottrell. If the 100 students. and the behavior of some party volume of a particular party is "At this particular address (601 goers, Parent said yesterday at a louder than 55 decibels, the max E. -

Front Matter

Ingrassia_Gridiron 11/6/15 12:22 PM Page vii © University Press of Kansas. All rights reserved. Reproduction and distribution prohibited without permission of the Press. Contents List of Illustrations ix Acknowledgments xi INTRODUCTION The Cultural Cornerstone of the Ivory Tower 1 CHAPTER ONE Physical Culture, Discipline, and Higher Education in 1800s America 14 CHAPTER TWO Progressive Era Universities and Football Reform 40 CHAPTER THREE Psychologists: Body, Mind, and the Creation of Discipline 71 CHAPTER FOUR Social Scientists: Making Sport Safe for a Rational Public 93 CHAPTER FIVE Coaches: In the Disciplinary Arena 115 CHAPTER SIX Stadiums: Between Campus and Culture 139 CHAPTER SEVEN Academic Backlash in the Post–World War I Era 171 EPILOGUE A Circus or a Sideshow? 200 Ingrassia_Gridiron 11/6/15 12:22 PM Page viii © University Press of Kansas. All rights reserved. Reproduction and distribution prohibited without permission of the Press. viii Contents Notes 207 Bibliography 269 Index 305 Ingrassia_Gridiron 11/6/15 12:22 PM Page ix © University Press of Kansas. All rights reserved. Reproduction and distribution prohibited without permission of the Press. Illustrations 1. Opening ceremony, Leland Stanford Junior University, October 1891 2 2. Walter Camp, captain of the Yale football team, circa 1880 35 3. Grant Field at Georgia Tech, 1920 41 4. Stagg Field at the University of Chicago 43 5. William Rainey Harper built the University of Chicago’s academic reputation and also initiated big-time athletics at the institution 55 6. Army-Navy game at the Polo Grounds in New York, 1916 68 7. G. T. W. Patrick in 1878, before earning his doctorate in philosophy under G. -

Commencement Guide

COMMENCEMENT GUIDE MAY | 2019 FROM THE PRESIDENT To the families of our graduates: What an exciting weekend lies ahead of you! Commencement is a special time for you to celebrate the achievements of your student. Congratulations are certainly in order for our graduates, but for you as well! Strong support from family allows our students to maximize their potential, reaching and exceeding the goals they set. As you spend time on our campus this weekend, I hope you will enjoy seeing the lawns and halls where your student has created memories to last a lifetime. It has been our privilege and pleasure to be their home for these last few years, and we consider them forever part of our UA family. We hope you will join them and return to visit our campus to keep this relationship going for years to come. Because we consider this such a valuable time for you to celebrate your student’s accomplishments, my wife, Susan, and I host a reception at our home for graduates and their families. We always look forward to this time, and we would be delighted if you would join us at the President’s Mansion from 1:00 to 3:00 p.m. on Friday, May 3. Best wishes for a wonderful weekend, and Roll Tide! Sincerely, Stuart R. Bell SCHEDULE OF EVENTS All Commencement ceremonies will take place at Coleman Coliseum. FRIDAY, MAY 3 Reception for graduates and their families Hosted by President and Mrs. Stuart R. Bell President’s Mansion Reception 1:00 - 2:00 p.m. -

Central Campus Medical Campus

D. R R LLE FU CENTRAL CAMPUS & MEDICAL CAMPUS MEDICAL 1 R DR. ENTE P BUILDING DIRECTORY SCHOOL L C A P CAMPUS F5 Alumni Center E5 Rackham Building OF NURSING IC D P D8 Angell Hall F8 Randall Laboratory (RAND) KKINGSLINGSLEY ST. E P . M UNIVERSITY HOSPITAL . T T E S C7 Betsy Barbour Residence (BBR) E11 Ross School of Business (ROSS) S W . 2 E5 Burton Memorial Tower G7 Ruthven Museums M E LLS H7 Central Campus Recreation Building (CCRB) F9 Shapiro Undergraduate Library (UGL) LLS D I C GA GA F6 Chemistry Building (CHEM) F10 School of Social Work A L E9 Clements Library (CL) D10 South Hall C N. IN N. IN E E9 Martha Cook Residence (COOK) C10 South Quad P N CATHERHERINE ST. T . TAUBMAN E E H4 Couzens Hall D5 202 S. Thayer Building (THAYER) E LIBRARY R R 3 V V D E A F7 Dana Building, School of Natural H6 Stockwell Hall A R H TAUBMAN MOLECULAR AND P . Resources & Environment (DANA) C8 Student Activities Building (SAB) C BIOMEDICAL SCIENCE BEHAVIORAL T I RESEARCH NEUROSCIENCE P GLEN GLEN G8 Dennison Building (DENN) D9 Tappan Hall (TAP) GRADUATE DETROIT A P Taubman Biomedical Science Research Building E. ANN ST. OBSERVATORY G6 School of Dentistry (DENT) G4 HOTEL N I I3 Detroit Observatory G3 Taubman Library Z COUZENS F7 Dow Laboratory (DOW) D8 Tisch Hall 4 G9 East Hall I9 Trotter Multicultural Center LL E. MEDMEDIICAL CENTERCENTER DR. E. HHUURON ST. P O ALMER FIELD P OWE G11 East Quad (Residential College) G5 Undergraduate Science Building (USB) Y D MARY F10 School of Education F5 University Health Service (UHS) RACKHKHAAM POWER P MARKLEY R A P CENTER LM F11 Executive Education J2 University Hospital NORTH L HALL A N QUAD E C8 Fleming Administration Building D11 Weill Hall (Ford School) R R E. -

2008 Alabama FB Game Notes

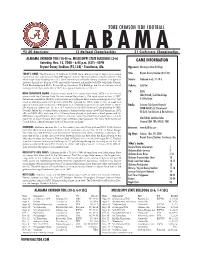

2008 CRIMSON TIDE FOOTBALL 92 All-Americans ALABAMA12 National Championships 21 Conference Championships ALABAMA CRIMSON TIDE (10-0) vs. MISSISSIPPI STATE BULLDOGS (3-6) GAME INFORMATION Saturday, Nov. 15, 2008 - 6:45 p.m. (CST) - ESPN Bryant-Denny Stadium (92,138) - Tuscaloosa, Ala. Opponent: Mississippi State Bulldogs TODAY’S GAME: The University of Alabama football team returns home to begin a two-game Site: Bryant-Denny Stadium (92,138) homestand that will close out the 2008 regular season. The top-ranked Crimson Tide host the Mississippi State Bulldogs in a SEC West showdown at Bryant-Denny Stadium. The game is Series: Alabama leads, 71-18-3 slated to kickoff at 6:45 p.m. (CST) and will be televised nationally by ESPN with Mike Patrick, Todd Blackledge and Holly Rowe calling the action. The Bulldogs are 3-6 on the season and Tickets: Sold Out coming off of a bye week after a 14-13 loss against Kentucky on Nov. 1. TV: ESPN HEAD COACH NICK SABAN: Alabama head coach Nick Saban (Kent State, 1973) is in his second season with the Crimson Tide. He was named the school’s 27th head coach on Jan. 3, 2007. Mike Patrick, Todd Blackledge Saban has compiled a 108-48-1 (.691) record as a collegiate head coach, including an 17-6 (.739) & Holly Rowe mark at Alabama and a 10-0 record in 2008. He captured his 100th career victory in week two against Tulane and coached his 150th game as a collegiate head coach in week three vs. West- Radio: Crimson Tide Sports Network ern Kentucky. -

Field of Dreams: the Vision for the LTU Athletics Complex, and How You

LAWRENCE TECHNOLOGICAL UNIVERSITY MAGAZINE | Summer/Fall 2017 Field of dreams: The vision for the LTU athletics complex, and how you can be a part of it Meet LTU’s athletic coaches | President Moudgil visits India, China Breaking ground for a fourth residence hall | New DECA team shines | Alumni news | And more! Summer/Fall 2017 Volume XXXVI, Number 1 Published by Lawrence Technological University, Office of Marketing and Public Affairs, 21000 West Ten Mile LAWRENCE TECHNOLOGICAL UNIVERSITY MAGAZINE Road, Southfield, MI 48075-1058; 248.204.2200 or 800.225.5588, ext. 4 Fax 248.204.2318 FROM THE PRESIDENT [email protected] Virinder K. Moudgil President Editor: Bruce J. Annett, Jr. ([email protected]) Managing Editor: Matt Roush ([email protected]) With the start of fall semester, we mark the 85th anniversary Design: NetWorks Design, Inc. of the founding of Lawrence Technological University. On Writers: Bruce J. Annett, Jr., Stephanie September 6, 1932, Lawrence Institute of Technology opened with Casola, Sibrina Collins, Chris Mead, the first class of several hundred students. Jay Nicols, Matt Roush Editorial Support: Anne Adamus, It is hard to imagine a less promising time to launch a new Krysta Coleman, Howard Davis, enterprise. During what historians generally agree were the bleakest Kristen DeVries, Sofia Lulgjuraj, Brandé Oliver, Kristine L. Persinger, Lauren months of the worst economic year of the Great Depression, LTU Seebold, Julie Vulaj founder Russell Lawrence, supported by close members of his family Photography and Illustration: The Virinder K. Moudgil and a band of stalwart faculty, bravely faced the future. Collaborative, Gary Duncan, inFORM, Matt Lester, Justin Munter, Jay Nicols, Michigan’s unemployment rate was pushing 50 percent. -

Parking Map May2018

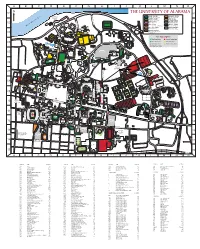

A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O N 01 01 e r NORTH CAMPUS WAY BLUE SPACES ORANGE ZONES i v The Park at Handicapped Parking Resident Parking R Manderson Tuscaloosa, Alabama Landing GREEN ZONES o r TAN ZONES r i AY Faculty/Sta Parking Resident Parking r ARKW a E PINK SPACES SILVER ZONES N W ARNER P A =Time mo Limittorcycle space inR theesiden ta Prareaking L 02 k 2497 JACK W RED ZONES TAN ZONES 02 c Y RED ZONES l a 2601 R 2665 Commuter Student Parking BLACKReside ZONESnt Parking R Commuter Student Parking Reserved Parking B E 2600 2664 B and Perimeter Parking K YELLOW ZONES C 2667 PURPLE ZONES A Resident Parking H Perimeter Parking 2602 KIRKBRIDE LANE YELLOW ZONES 2666 SILVER ZONES D L 2670 BROWNReside SPACESnt Parking Resident Parking O 2669 Multi-Space Pay Stations, 2668 Pay by Space 03 3429 03 A BE NE 3430 ORANGE ZONES RCROMBIE LA Resident Parking HARPER CT. 3444 Bus Stop Legend 2265 2263 Blue Route Stops Crimson Route Stops 2261 2264 2262 D288 3440 2266 Green Route Stops Gold Route Stops 04 2270 Palmer HACKBERR PETER BRYCE BLVD. Silver Route Stops 04 Lake Y LANE 3441 Mul�ple Route Stops 2269 2267 3427 KIRKBRIDE LANE Bronze Route Stops L 3426 1252 Capital SECOND STREET LANE SHELBY 2272 D A Construction Hall O Area McF R 05 ARLAND BOULEV 05 G 2271 1249 3415 3419 N I 2093 2247 R P DRIVE S 1401 D284 S VEY E 3423 R N 3446 LA ARD R RE A O KILG M 3422 McCOR 1245 12451236 D286 3420 VENUE Construction A 1251 06 Area Construction 3418 06 Area EST 3421 W SEVENTH 1021 Northeast 2035 1022 Commuter E Bryant Jordan IV DR 3417 Zone Parking ten Hoor 1254 E 2332 1079 E V 1235 V HACKBERRY LANE HACKBERRY I 1043 I Performing R 2106 R 5370 D D 07 Hall 5365 N N 07 S W W Arts Center U A P 1043 A L MARR’S SPRING RD. -

The University of Michigan

University of Michigan Law School University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository Michigan Legal Studies Series Law School History and Publications 1969 The niU versity of Michigan: Its Legal Profile William B. Cudlip Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/michigan_legal_studies Part of the Education Law Commons, and the State and Local Government Law Commons Recommended Citation Cudlip, William B. The nivU ersity of Michigan: Its Legal Profile. Ann Arbor: Univ. of Michigan, 1969. This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School History and Publications at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Michigan Legal Studies Series by an authorized administrator of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN: ITS LEGAL PROFILE THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN: ITS LEGAL PROFILE by William B. Cudlip, J.D. Published under the auspices of The University of Michigan Law School (which, however, assumes no responsibility for the views expressed) with the aid of funds derived from a gift to The University of Michigan by the Barbour-Woodward Fund. Copyright© by The University of Michigan, 1969 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I suppose that lawyers are always curious about the legal history of any institution with which they are affiliated. As the University of Michigan approached its One Hundred Fiftieth year, my deep interest was heightened as I wondered about the legal structure and involvements of this durable edifice over that long period of time. This compendium is the result and I acknowledge the help that I have had. -

UA Crimsonride Back in Service Today

Softball goes 4-1 over A&E SPORTS weekend Telepath to perform 10 tonight 14 Wednesday, March 3, 2010 Serving the University of Alabama since 1894 Vol. 116, Issue 97 UA CrimsonRide back in service today. I missed you.” Transit officials Tuesday to A Crimson- Offi cials plan limited bus service Some students seem to have discuss the dispute. In May Ride bus be- a greater appreciation for all 2009, the drivers voted to union- hind Gorgas until contract agreement of the bus drivers after a day ize under the Amalgamated Library. on foot, and some riders even Transit Union, but First By Amanda Sams Ryan McGuire, a junior, said seemed concerned with the Transit has stalled contract CW | Rachel Hill Staff Writer he was excited to see one of his outcome of the strike against negotiations, union officials favorite bus drivers, Yorlando First Transit. said in February, which led to After CrimsonRide bus driv- Hurl, back on her normal route. While drivers don’t have any the strike. ers went on strike Monday to The two greeted each other new information on the effec- CrimsonRide bus drivers fight for more benefits, high- excitedly and began to catch tiveness of their strike, Hurl are not UA employees. They er wages and maintenance up on current events. In the said she is optimistic that First work under contract with First repairs on their buses, a num- course of five minutes, another Transit is willing to “go back to Transit, a transportation ber of drivers went back to student boarded the bus and the bargaining table.” work Tuesday. -

Dan Devine Rudy Premieres at Morris Civic Auditorium

---- -~ ~ ----- -----~------------ ------ ------ Thursday, October 7, 1993 • Vol. XXVI No. 29 THE INDEPENDENT NEWSPAPER SERVING NOTRE DAME AND SAINT MARY'S Dan Devine Rudy premieres at Morris Civic Auditorium By KENYA JOHNSON upset, but Accent Editor South Bend donned the glit will not sue ter of Hollywood last night for the first time since 1940. host By JOHN LUCAS ing celebrities and a sellout Associate News Editor crowd of 2.400 for the pre miere of Tri-Star Pictures' Although he is upset by his "Rudy" at the Morris Civic portrayal in the new Auditorium. film "Rudy ... former Notre Cast members Sean Astin. Dame football coach Dan Ned Beatty and Robert Prosky Devine will not take legal greeted reporters and hun action against Tri-Star dreds of spectators as they Pictures, citing both his wife's exited limousines and walked health and his commitments to up the red carpet into the the the University of Missouri as ater. more important priorities in his life. "This is all so wonderful." "Basically. there's not going said Astin. who portrays Rudy to be any lawsuit," Devine said. in the film. 'Tm very excited "But I want to say that I was to be here. This is an inspira one of the most loyal and de tional story. a human interest voted Notre Dame people in kind of movie. I hope you all the country. and I am very. enjoy it as much as I have." very. dissappointed in the way But as Astin arrived. "Rudy" the University handled this was the only name on the situation." throng's lips. -

Five-Year Master Plan University of Michigan-Ann Arbor FY2019

Five-Year Master Plan University of Michigan-Ann Arbor FY2019 Prepared by: University of Michigan-Ann Arbor Facilities and Operations October 31, 2017 FIVE-YEAR MASTER PLAN UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN-ANN ARBOR FY2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Mission Statement Page 3 II. Instructional Programming Page 5 III. Staffing and Enrollment Page 23 IV. Facility Assessment Page 44 V. Implementation Plan Page 72 VI. Capital Outlay Project Request FY19 Page 84 2 MISSION STATEMENT The mission of the University of Michigan is to serve the people of Michigan and the world through preeminence in creating, communicating, preserving and applying knowledge, art, and academic values, and in developing leaders and citizens who will challenge the present and enrich the future. VISION STATEMENT As the University of Michigan prepares to embark on its third century, we fully embrace the legacy bestowed upon us by President James B. Angell in our first century. We are proud to offer “an uncommon education for the common man.” We are a community of learners. We serve our multiple constituents by providing access to and participation in scholarly and creative endeavors on a vast scale. Our academic research enterprise affects the world. The university is defined by a culture of interdisciplinary teaching and research, coupled with academic rigor. We encourage our students, faculty, and staff to transcend disciplinary boundaries by tackling complex and vexing problems facing modern societies at local, national, and global levels. We endorse and promote creativity in its many facets. We recognize the arts as a human essential and a foundation that helps to define our future.