UNICEF Lesotho

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Meghan and Harry That They Would Have to Accept What Was on Offer and Not Demand What Was Not

Contents Title Page Chapter 1 Chapter 2 Chapter 3 Chapter 4 Chapter 5 Chapter 6 Chapter 7 Chapter 8 Chapter 9 Chapter 10 Chapter 11 Chapter 12 Photo Section Copyright CHAPTER 1 On May 19th 2018, when Meghan Markle stepped out of the antique Rolls Royce conveying her and her mother Doria Ragland from the former Astor stately home Cliveden to St. George’s Chapel, Windsor, where she was due to be married at 12 noon, she was a veritable vision of loveliness. At that moment, one of the biggest names of the age was born. As the actress ascended the steps of St. George’s Chapel, its interior and exterior gorgeously decorated in the most lavish and tasteful spring flowers, she was a picture of demure and fetching modesty, stylish elegance, transparent joyousness, and radiant beauty. The simplicity of her white silk wedding dress, designed by Clare Waight Keller of Givenchy, with its bateau neckline, three-quarter length sleeves, and stark, unadorned but stunningly simple bodice and skirt, coupled with the extravagant veil, five metres long and three metres wide, heavily embroidered with two of her favourite flowers (wintersweet and California poppy, as well as the fifty three native flowers of the various Commonwealth countries, and symbolic crops of wheat, and a piece of the blue dress that the bride had worn on her first date with the groom), gave out a powerful message. All bridal gowns make statements. Diana, Princess of Wales, according to her friend Carolyn Pride, used hers to announce to the world, ‘Here I am. -

Abstracts from the Regional Psychosocial Support Forum 2013

Regional Psychosocial Support Forum 2013 Mainstreaming Psychosocial Support for Child Protection: Linking Evidence and Practice Book of Abstracts October 29 – 31 Kenyatta International Conference Centre Nairobi Kenya Contents PLENARY SEssIONS 5 Plenary 1: 6 Plenary 2: 8 Plenary 3: 10 Plenary 4: 13 TRACK SEssIONS 17 Track 1: Child Protection Programs 1 18 Track 2: Parenting 22 Track 3: Highly vulnerable populations 23 Track 4: Economic Strengthening 27 Track 5: Disclosure 30 Track 6: Education 33 Track 7: Humanitarian Emergencies 1 36 Track 8: Child Trafficking & Labour 39 Track 9: Child Protection Programs 2 42 Track 10: Humanitarian Emergencies 2 47 Track 11: Children Living with HIV 1 52 Track 12: Children Living with HIV 2 56 Track 13: Capacity Building for CP Systems Strengthening 59 Track 14: Children Living with Disability 62 Track 15: Child Protection Programmes 3 65 Contents SKILLS BUILDING SEssIONS AND SPECIAL SESSIONS 70 Skills Building Session 1: 71 Skills Building Session 2: 73 Skills Building Session 3: 74 Skills Building Sessions 4: 75 Skills Building Session 5: 77 Skills Building Session 6: 77 Skills Building Session 7: 78 Skills Building Session 8: 79 Special Session 1: 80 Special Session 2: 81 Special Session 3: 82 Special Session 4: 83 ACKNOWLEDGEMENts 84 Plenary Sessions 5 Plenary 1: GOVERNMENT OF KENYA: CHILD PROTECTION FRAMEWORK Ahmed Hussein (Government of Kenya) Abstract not available at time of printing INTEGRATION OF PSYCHOSOCIAL SUppOrt IN CARE AND SUppOrt TO OVC: A HOLIstIC ApprOACH Ana Rosa Durão Gama Mondle, Linda Lovick, Juliana Canjera, Integration of Psychosocial Support in Care and Support to OVC A Holistic Approach Issues: In Mozambique, as in many other developing countries, orphans and vulnerable children (OVC) living in households affected by HIV/AIDS are turned into caregivers for sick parents, and also for their younger brothers and sisters. -

LESOTHO Global AIDS Response Country Progress Report January

LESOTHO Global AIDS Response Country Progress Report Towards Zero new infections, Zero AIDS related deaths and zero discrimination. January 2010-December 2011 STATUS OF THE NATIONAL RESPONSE TO THE 2011 POLITICAL DECLARATION ON ( March 26, 2012) ii iii TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0. BACKGROUND ................................................................................................................ 21 1.2. Development of the 2011 Global AIDS Progress Country Report ........................................21 1.3. National Composite Policy Index Questionnaire.......................................................................22 2.0. HIV AND AIDS IN LESOTHO AT 2011 ............................................................................23 2.1. Lesotho Country Profile.................................................................................................................23 2.2. Status of HIV and AIDS in Lesotho............................................................................................25 2.3. Epidemic Drivers ............................................................................................................................28 3.0. PROGRESS IN RESPONDING TO HIV AND AIDS 2010-2011...............................................33 3.1. Overall achievements since 2009..................................................................................................33 3.10. Prevention....................................................................................................................................37 -

AIDS, Orphan Care and the Family in Lesotho by Mary Ellen Block A

Infected Kin: AIDS, Orphan Care and the Family in Lesotho by Mary Ellen Block A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Social Work and Anthropology) in The University of Michigan 2012 Doctoral Committee: Professor Elisha P. Renne, Co-Chair Associate Professor Karen M. Staller, Co-Chair Professor Gillian Feeley-Harnik Associate Professor Letha Chadiha Lecturer Holly Peters-Golden © Mary Ellen Block 2012 Ho bana le baholisi ba bona . ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I dedicate this dissertation to the babies and caregivers ( ho bana le baholisi ba bona ) of Mokhotlong who helped reveal to me the many challenges of the AIDS orphan crisis, and without whom this work would not be possible. From my earliest days in Mokhotlong, they opened their homes to me and shared with me their most personal and painful stories for reasons I cannot begin to imagine. People willingly and cheerfully gave me their time, entry into their private spaces and their friendship, and for that I am truly humbled and grateful. The MCS staff deserves special mention. The safe home bo’m’e (house mothers) were always welcoming, friendly and ready to laugh at my attempts at humor in Sesotho. I am particularly indebted to the outreach workers with whom I spent countless hours driving around the Lesotho countryside chatting, sleeping, and asking obvious and countless questions. For their knowledge, time and patience I am forever in their debt. To my trusted, wonderful and delightful research assistant, Ausi Ntsoaki, who drove hundreds of miles with me on the back of my dirt bike, who spent painstaking hours transcribing interviews with me, and who made every day in the field not only easier, but truly enjoyable. -

Register of Lords' Interests

REGISTER OF LORDS’ INTERESTS _________________ The following Members of the House of Lords have registered relevant interests under the code of conduct: ABERDARE, LORD Category 10: Non-financial interests (a) Director, F.C.M. Limited (recording rights) Category 10: Non-financial interests (c) Trustee, National Library of Wales Category 10: Non-financial interests (e) Trustee, Stephen Dodgson Trust (promotes continued awareness/performance of works of composer Stephen Dodgson) Chairman and Trustee, Berlioz Sesquicentenary Committee (music) Chairman and Trustee, Berlioz Society Trustee, St John Cymru-Wales (interest ceased 21 September 2018) Trustee, West Wycombe Charitable Trust ADAMS OF CRAIGIELEA, BARONESS Nil No registrable interests ADDINGTON, LORD Category 1: Directorships Chairman, Microlink PC (UK) Ltd (computing and software) Category 7: Overseas visits Visit to Baku, Azerbaijan, 18-22 September 2018, to celebrate centenary of country’s declaration of independence; flights and accommodation costs paid by Azerbaijan Embassy, London Category 8: Gifts, benefits and hospitality Two tickets and hospitality provided by Football Association to Manchester City v Watford FA Cup Final, Wembley Stadium, 18 May 2019 Category 10: Non-financial interests (a) Director and Trustee, The Atlas Foundation (registered charity; seeks to improve lives of disadvantaged people across the world) Category 10: Non-financial interests (d) President (formerly Vice President), British Dyslexia Association Category 10: Non-financial interests (e) Vice President, UK Sports Association Vice President, Lakenham Hewitt Rugby Club ADEBOWALE, LORD Category 1: Directorships Director, Leadership in Mind Ltd (business activities; certain income from services provided personally by the member is or will be paid to this company; see category 4(a)) Director, IOCOM UK Ltd (visual business platform) Independent Non-executive Director, Co-operative Group Board of Directors (consumer co-operative) Category 2: Remunerated employment, office, profession etc. -

OVC Evaluation Report 170412

SUPPORT TO LESOTHO HIV AND AIDS RESPONSE: EMPOWERMENT OF ORPHANS AND OTHER VULNERABLE CHILDREN Final Evaluation Anne Thomson and Andrew Kardan 17 April 2012 Final Evaluation of Support to Lesotho HIV and AIDS Response: Empowerment of Orphans and Other Vulnerable Children Acknowledgements This report was written by Anne Thomson and Andrew Kardan from Oxford Policy Management based on review and analysis of secondary data and key informant interviews in Maseru, districts and community councils. During this time we received generous support from many people. First and foremost our special thanks go to Farida Noureddine from UNICEF for her continual guidance and advice on the study. She worked tirelessly in ensuring we had access to and met with as many important stakeholders as was possible. We are also grateful to several of her colleagues at UNICEF who provided us with their time, knowledge and resources. We thank all the staff at the DSW in Maseru for their very useful information and insights on the project as a whole. The DSW staffs at the districts were very kind in providing us with time and coordinating and facilitating all our meetings at very short notice and we thank them for this. The field work also benefited from the translation support of Moeketsi Ratikane and Masilo Tsewoli Kose and facilitation of Ntate Maphika. We thank staff from the European Delegation for hosting us during the validation process and presentation of our preliminary findings. We are also grateful to our colleagues Alex Hurrell, Luca Pellerano and Ian MacAuslan for their review and comments on our earlier draft. -

Report & Accounts

REPORT & ACCOUNTS YEAR ENDED 31 AUGUST 2015 MOZAMBIQUE BOTSWANA NAMIBIA AFRICA SWAZILAND LESOTHO SENTEBALE HOW WE’VE HELPED THE MOST VULNERABLE CHILDREN IN LESOTHO IN THE YEAR 2014/2015 SOUTH AFRICA ’MAMOHATO CHILDREN’S LESOTHO CENTRE IS OPEN ALLOWING US TO REACH 1,500 PER YEAR AT CAPACITY INCREASE2% INCREASE44% INCOMING LOCAL HIV REMAINS RESOURCES CHARITABLE O OVER EXPENDITURE PROGRAMME DELIVERY HIGHLIGHTS NCAUSE OF DEATH1 IN HALFOF THE POPULATION 10-19 YEAR OLDS ARE LIVING IN IN AFRICA Source: WHO Global Health Estimates, 2014 POVERTYSource: UNDP Human Development Report, 2013 GIRLS ACCOUNTED FOR POPULATION OVER 2 MILLION Source: World Health Statistics, 2014 NETWORK CLUBS MORE 58OF ADOLESCENTS% >CAREGIVERS300 WORLD’S SECOND THAN DOUBLED ATTENDING RECEIVED CHILDCARE NETWORK CLUBS TRAINING HIGHEST in CHILDREN1 3 INFECTION RATE IS AN ORPHAN HIVSource: CIA World Factbook, 2014 Source: Lesotho Ministry of Development, 2013 4INCREASE0% COUNTRY, LANDLOCKED BY SOUTH AFRICA LANDLOCKED BY COUNTRY, THE KINGDOM OF LESOTHO IS A SMALL & MOUNTAINOUS & MOUNTAINOUS A SMALL IS LESOTHO OF KINGDOM THE SECONDARY 30% SCHOOL INCREASE BURSARIES PSYCHOSOCIAL SUPPORT ON 60,000 PREVIOUS YEAR , ONLY STIGMA PEER EDUCATORS 21AGED BETWEEN000 10 & 19 118TRAINED TO DELIVER IS THE BIGGEST CLUBS AND CAMPS DELIVERED LIFE SKILLS AND HIV LIVING WITH % MORE THAN 60,000 HOURS PREVENTION ADVICE 30 BARRIER OF PSYCHOSOCIAL SUPPORT TO 10-19 YEAR-OLDS ACCESS TO YOUTH ACCESSING % TREATMENT INCREASE66 TERTIARY EDUCATION BURSARIES Source: All in to End Adolescent AIDS – CARESource: Ki-moon, The Stigma Factor, 2008 HIVLesotho Fact Sheet, 2015 LESOTHO 2 3 SENTEBALE ABOUT CONTENTS Sentebale is a charity founded in 2006 by Prince Harry of the United Kingdom and Prince Seeiso of Lesotho. -

Report and Accounts Year Ended 31 August 2019

REPORT AND ACCOUNTS YEAR ENDED 31 AUGUST 2019 Sentebale 17 Gresse Street 6 Evelyn Yard Entrance London W1T 1QL I sentebale.org ©2020 SENTEBALE. SENTEBALE IS A REGISTERED CHARITY (CHARITY NO. 1113544). COMPANY NUMBER 05747857. Contents Founding Patrons’ Foreword 4 Message from the Chairman 6 Message from the CEO 7 The Global HIV Landscape 8 Year in Numbers 9 Our Vision and Strategy 10 Progress against Programme Priorities 12 Spotlight on Fundraising 26 Future Priorities 29 Acknowledgements 32 Company Directory 32 Financial Report 34 Financial Policies 36 Statement of Trustees’ Responsibilities 38 Independent Auditor’s Report to the Members of Sentebale 39 Statement of Financial Activities 41 Balance Sheet as at 31 August 2019 42 Statement of Cash Flows: Year to 31 August 2019 43 Notes to the Financial Statements 44 2 3 FOUNDING PATRONS’ FOREWORD In the 13 years since Sentebale was founded the organisation has gone from strength to strength. We are very proud of all that has been achieved. From small beginnings, the organisation is now firmly established in Lesotho – with a strong base at the unique ‘Mamohato Centre – and has a growing presence in Botswana. Our flagship clubs and camps programme reaches supporting its work long into the future. In August, some of the most remote communities in Prince Seeiso joined the second Let Youth Lead Southern Africa, providing essential life skills and Summit in Gaborone, Botswana – it was inspiring psycho-social support to children living with HIV. to hear how much Sentebale is supporting this It is delivered in a fun, friendly and safe environment incredible network of youth leaders. -

SB Randa 15 16 Sigs Tweaked Blue for TC.Indd

REPORT YEAR ENDED & ACCOUNTS 31 AUGUST 2016 THE GLOBAL SENTEBALE’S HIV LANDSCAPE RESPONSE UNAIDS 2020 Fast Track Targets Delivered HIV testing and counselling services to over 16,500 people in Lesotho. All of those found HIV-positive between the ages of 9-19 years were refered to Sentebale’s Saturday clubs 90% 90% 90% Psychosocial support to help achieve viral suppression of people of people of people 18% increase in the number of children attending club compared to the previous year Doubled the number of children attending camp compared to the previous year 99% of children leave camp confi dent and hopeful about the future living with living with HIV who on treatment HIV know their know their status are have suppressed status receiving treatment viral loads Top-line achievements For the fi rst time in the history of this epidemic, we can say that Africa has reached the tipping point. More Africans are newly initiating treatment ’MAMOHATO than are being newly infected with HIV. Reaching INCREASE27% INCREASE14% CHILDREN’S CENTRE this turning point is truly amazing, and few people IN IN IN-COUNTRY OFFICIALLY INCOME CHARITABLE EXPENDITURE IN OPENED believed this could be achieved by now.” LOCAL CURRENCY NOVEMBER 2015 MICHEL SIDIBE, UNAIDS EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR, 2016 However Advocated for change in the AIDS response THERE ARE HIV REMAINS O YOUTH KENSINGTON PALACE GARDENS AIDS MILLION NCAUSE OF DEATH1 IN LONDON 2.1 ADOLESCENTS CONFERENCE ADOLESCENTS LIVING WITH HIV IN AFRICA Source: UNAIDS, 2015 Source: UNAIDS, 2015 2 3 OUR MISSION To become the leading organisation in the provision of psychosocial support for children living with HIV in southern Africa. -

Polo League Beach Polo - Miami · Westchester Cup · Sentebale Isps Handa Polo Cup

VOLUME III / ISSUE VI / JUNE 2019 WORLD POLO LEAGUE BEACH POLO - MIAMI · WESTCHESTER CUP · SENTEBALE ISPS HANDA POLO CUP CANNES FILM FESTIVAL COUTURE & FASHION MET GALA 2019 WHO REALLY INVENTED CAMP? POLO FOR GOOD SENTEBALE ISPS HANDA POLO CUP THE DUKE OF SUSSEX & FRIENDS ROOFTOPS & ROMAN VISTAS · ON & OFF THE FIELD: US POLO ASSN APPAREL DIOR'S TIEPOLO BALL · AN ACID TRIP TO REMEMBER THE WORLD'S FASTEST SAILBOATS: SAILGP $27.95 USD VOLUME III / ISSUE VI / JUNE 2019 WWW.POLOLIFESTYLES.COM POLO FOR GOOD IN THE ETERNAL CITY THE ROMA POLO CLUB, ST. REGIS & U.S. POLO ASSN. HOST SENTEBALE'S ANNUAL CHARITY POLO CUP page 74 page 75 VOLUME III / ISSUE VI / JUNE 2019 WWW.POLOLIFESTYLES.COM POLO FOR GOOD SENTEBALE ST. REGIS 9 / 6 U.S. POLO ASSN. ROMA POLO CLUB SUPPORTING THE DUKE OF SUSSEX CHARITY SENTEBALE THAT CARES FOR CHILDREN LIVING WITH HIV/AIDS page 76 page 77 VOLUME III / ISSUE VI / JUNE 2019 WWW.POLOLIFESTYLES.COM THE DUKE OF SUSSEX IN ROME FOR POLO ROME – An international, replete with a lemon backdrop served as diverse as its worldwide audience, Prince Seeiso Bereng Seeiso. In the later made a charity speech that eve- brand maintains and nurtures its roots jet-set crowd mingled with up specialty cocktails of Royal Salute from colorful polos to chic accesso- last nine years, Sentebale’s flagship ning at the St. Regis Midnight Supper. while appealing to a global market. Italian elite on the sidelines made with hand-sawn ice cubes a la ries, donned by many of the spectators event – the Polo Cup – has traveled minute. -

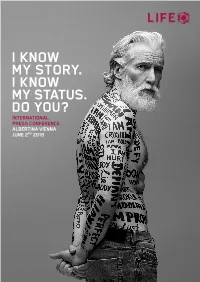

I Know My Story. I Know My Status. Do You?

I KNOW MY STORY. I KNOW MY STATUS. DO YOU? INTERNATIONAL PRESS CONFERENCE ALBERTINA VIENNA JUNE 2ND 2018 Life Ball Press Office: T +43 (0) 1 595 56 00 20, F +43 (0) 1 595 56 77, [email protected] www.lifeplus.org | www.lifeball.org Printed with love by druck.at Graphics & Layout: WebArtists - Günter Temel / Gaby Lucano Art Director: Michael Balgavy Cover: © © Rankin, 2018. Model: Aiden Brady / © Rankin, 2018. Model: Eva Herzigová / © Rankin, 2018 Campaign Design: Merlicek & Grossebner English Translation: Globe Comm Translation Services Photos of the press conference can be found in the photo library of Life Ball at https://media.lifeplus.org, a voluntary service by mediamid digital services GmbH Content Foreword .................................................................................................... 2 LIFE+ FIGHTING AIDS AND CELEBRATING LIFE SINCE 1992 .........................................4 ABOUT HIV/AIDS ........................................................................................... 5 INTERNATIONAL PROJECTS & PARTNERS OF LIFE+ .................................................. 7 INTERNATIONAL IMPACT ................................................................................. 8 ECONOMIC IMPACT OF LIFE+ LIFE BALL: A POWERFUL BRAND ................................... 9 ECONOMIC FACTOR LIFE BALL .......................................................................... 9 LIFE+ CAMPAIGNS KNOW YOUR STATUS 2018 THE CAMPAIGNS OF LIFE+ ....................... 10 AN OVERVIEW OF THIS YEAR’S LIFE BALL EVENTS ............................................... -

Care and Treatment Values, Preferences, and Attitudes of Adolescents Living with HIV

WHO/HIV/2013.136 © World Health Organization 2013 HIV and adolescents: guidance for HIV testing and counselling and care for adolescents living with HIV ANNEX 11 (a): Values and preferences: ALHIV survey Care and treatment values, preferences, and attitudes of adolescents living with HIV A survey for the development of WHO guidelines for HIV and adolescents: guidance for HIV testing and counselling and care for adolescents living with HIV: recommendations for a public health approach 1 Table of Contents Acknowledgements Abbreviations and acronyms Executive Summary 1. Introduction 2. Objectives 3. Methodology 3.1 Survey design 3.2 Distribution of the survey 3.3 Ethical considerations 3.4 Survey participants 3.5 Limitations of the survey 4. Key findings from survey 5. Discussion 6. Conclusions 7. Appendices 7.1 survey text in English 7.2 Key survey findings in table form Table 1. Final survey population by age Table 2. Final survey population by gender/sex Table 3. “If you are currently receiving paediatric or adolescent services, has/have your health- care provider(s) discussed how you will move to adult services?” (Q 16) Table 4. “How easy is it for you to access your health care?” (Q18) Table 5. “Do you feel that attending appointments with health-care providers interferes with your life?” (Q20) Table 6. “If you miss an appointment with a health-care provider, does someone contact you to see why?” (Q21) Table 7. “How comfortable do you feel asking any of your health-care providers questions about your general health?” (Q22) Table 8. “How comfortable do you feel asking any of your health-care providers questions about HIV?” (Q23) Table 9.