Charismatic Objects

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Contribution of Somali Diaspora in Denmark to Peacebuilding in Somalia Through Multi-Track Diplomacy

Journal of Ethnic and Cultural Studies Copyright 2021 2021, Vol. 8, No. 2, 241-260 ISSN: 2149-1291 http://dx.doi.org/10.29333/ejecs/642 The Contribution of Somali Diaspora in Denmark to Peacebuilding in Somalia through Multi-Track Diplomacy Sylvester Tabe Arrey The University of Buea, Cameroon Francisco Javier Ullán de la Rosa1 University of Alicante, Spain Abstract: The paper assesses the ways the Somali diaspora in Denmark is contributing to peacebuilding in their home country through what is known in peace studies as Multi-Track Diplomacy. It starts by defining the concepts of peacebuilding and Multi-track Diplomacy, showing how the latter works as an instrument for the former. The paper then describes and analyzes how, through a varied array of activities that include all tracks of diplomacy as classified by the Diamond&McDonald model, members of Danish diaspora function as interface agents between their home and host societies helping to build the conditions for a stable peace. The article also analyzes how the diplomacy tracks carried out by the Somali-Danish diaspora, as well as the extent of their reach, are shaped by the particular characteristics of this group vis-à-vis other Somali diasporic communities: namely, its small size and relatively high levels of integration and acculturation into the Danish host society. Keywords: Danish-Somalis, multi-track diplomacy, peacebuilding, Somalia, Somali diaspora. The Concepts of Peacebuilding and Multi-track Diplomacy Introduced for the first time by Galtung (1975), peacebuilding progressively became a mainstream concept in the field of peace studies (Heap, 1983; Young, 1987). The document an Agenda for Peace by UN Secretary-General Boutros-Ghali (Boutros-Ghali, 1992) can be considered its official come-of-age. -

Ritual Landscapes and Borders Within Rock Art Research Stebergløkken, Berge, Lindgaard and Vangen Stuedal (Eds)

Stebergløkken, Berge, Lindgaard and Vangen Stuedal (eds) and Vangen Lindgaard Berge, Stebergløkken, Art Research within Rock and Borders Ritual Landscapes Ritual Landscapes and Ritual landscapes and borders are recurring themes running through Professor Kalle Sognnes' Borders within long research career. This anthology contains 13 articles written by colleagues from his broad network in appreciation of his many contributions to the field of rock art research. The contributions discuss many different kinds of borders: those between landscapes, cultures, Rock Art Research traditions, settlements, power relations, symbolism, research traditions, theory and methods. We are grateful to the Department of Historical studies, NTNU; the Faculty of Humanities; NTNU, Papers in Honour of The Royal Norwegian Society of Sciences and Letters and The Norwegian Archaeological Society (Norsk arkeologisk selskap) for funding this volume that will add new knowledge to the field and Professor Kalle Sognnes will be of importance to researchers and students of rock art in Scandinavia and abroad. edited by Heidrun Stebergløkken, Ragnhild Berge, Eva Lindgaard and Helle Vangen Stuedal Archaeopress Archaeology www.archaeopress.com Steberglokken cover.indd 1 03/09/2015 17:30:19 Ritual Landscapes and Borders within Rock Art Research Papers in Honour of Professor Kalle Sognnes edited by Heidrun Stebergløkken, Ragnhild Berge, Eva Lindgaard and Helle Vangen Stuedal Archaeopress Archaeology Archaeopress Publishing Ltd Gordon House 276 Banbury Road Oxford OX2 7ED www.archaeopress.com ISBN 9781784911584 ISBN 978 1 78491 159 1 (e-Pdf) © Archaeopress and the individual authors 2015 Cover image: Crossing borders. Leirfall in Stjørdal, central Norway. Photo: Helle Vangen Stuedal All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyright owners. -

18Th Viking Congress Denmark, 6–12 August 2017

18th Viking Congress Denmark, 6–12 August 2017 Abstracts – Papers and Posters 18 TH VIKING CONGRESS, DENMARK 6–12 AUGUST 2017 2 ABSTRACTS – PAPERS AND POSTERS Sponsors KrKrogagerFondenoagerFonden Dronning Margrethe II’s Arkæologiske Fond Farumgaard-Fonden 18TH VIKING CONGRESS, DENMARK 6–12 AUGUST 2017 ABSTRACTS – PAPERS AND POSTERS 3 Welcome to the 18th Viking Congress In 2017, Denmark is host to the 18th Viking Congress. The history of the Viking Congresses goes back to 1946. Since this early beginning, the objective has been to create a common forum for the most current research and theories within Viking-age studies and to enhance communication and collaboration within the field, crossing disciplinary and geographical borders. Thus, it has become a multinational, interdisciplinary meeting for leading scholars of Viking studies in the fields of Archaeology, History, Philology, Place-name studies, Numismatics, Runology and other disciplines, including the natural sciences, relevant to the study of the Viking Age. The 18th Viking Congress opens with a two-day session at the National Museum in Copenhagen and continues, after a cross-country excursion to Roskilde, Trelleborg and Jelling, in the town of Ribe in Jylland. A half-day excursion will take the delegates to Hedeby and the Danevirke. The themes of the 18th Viking Congress are: 1. Catalysts and change in the Viking Age As a historical period, the Viking Age is marked out as a watershed for profound cultural and social changes in northern societies: from the spread of Christianity to urbanisation and political centralisation. Exploring the causes for these changes is a core theme of Viking Studies. -

Catalogue of the Famous Blackborne Museum Collection of Laces

'hladchorvS' The Famous Blackbome Collection The American Art Galleries Madison Square South New York j J ( o # I -legislation. BLACKB ORNE LA CE SALE. Metropolitan Museum Anxious to Acquire Rare Collection. ' The sale of laces by order of Vitail Benguiat at the American Art Galleries began j-esterday afternoon with low prices ranging from .$2 up. The sale will be continued to-day and to-morrow, when the famous Blackborne collection mil be sold, the entire 600 odd pieces In one lot. This collection, which was be- gun by the father of Arthur Blackborne In IS-W and ^ contmued by the son, shows the course of lace making for over 4(Xi ye^rs. It is valued at from .?40,fX)0 to $oO,0()0. It is a museum collection, and the Metropolitan Art Museum of this city would like to acciuire it, but hasnt the funds available. ' " With the addition of these laces the Metropolitan would probably have the finest collection of laces in the world," said the museum's lace authority, who has been studying the Blackborne laces since the collection opened, yesterday. " and there would be enough of much of it for the Washington and" Boston Mu- seums as well as our own. We have now a collection of lace that is probablv pqual to that of any in the world, "though other museums have better examples of some pieces than we have." Yesterday's sale brought SI. .350. ' ""• « mmov ON FREE VIEW AT THE AMERICAN ART GALLERIES MADISON SQUARE SOUTH, NEW YORK FROM SATURDAY, DECEMBER FIFTH UNTIL THE DATE OF SALE, INCLUSIVE THE FAMOUS ARTHUR BLACKBORNE COLLECTION TO BE SOLD ON THURSDAY, FRIDAY AND SATURDAY AFTERNOONS December 10th, 11th and 12th BEGINNING EACH AFTERNOON AT 2.30 o'CLOCK CATALOGUE OF THE FAMOUS BLACKBORNE Museum Collection of Laces BEAUTIFUL OLD TEXTILES HISTORICAL COSTUMES ANTIQUE JEWELRY AND FANS EXTRAORDINARY REGAL LACES RICH EMBROIDERIES ECCLESIASTICAL VESTMENTS AND OTHER INTERESTING OBJECTS OWNED BY AND TO BE SOLD BY ORDER OF MR. -

Bicycle Trips in Sunnhordland

ENGLISH Bicycle trips in Sunnhordland visitsunnhordland.no 2 The Barony Rosendal, Kvinnherad Cycling in SunnhordlandE16 E39 Trondheim Hardanger Cascading waterfalls, flocks of sheep along the Kvanndal roadside and the smell of the sea. Experiences are Utne closer and more intense from the seat of a bike. Enjoy Samnanger 7 Bergen Norheimsund Kinsarvik local home-made food and drink en route, as cycling certainly uses up a lot of energy! Imagine returning Tørvikbygd E39 Jondal 550 from a holiday in better shape than when you left. It’s 48 a great feeling! Hatvik 49 Venjaneset Fusa 13 Sunnhordland is a region of contrast and variety. Halhjem You can experience islands and skerries one day Hufthamar Varaldsøy Sundal 48 and fjords and mountains the next. Several cycling AUSTE VOLL Gjermundshavn Odda 546 Våge Årsnes routes have been developed in Sunnhordland. Some n Husavik e T YS NES d Løfallstrand Bekkjarvik or Folgefonna of the cycling routes have been broken down into rfj ge 13 Sandvikvåg 49 an Rosendal rd appropriate daily stages, with pleasant breaks on an a H FITJ A R E39 K VINNHER A D express boat or ferry and lots of great experiences Hodnanes Jektavik E134 545 SUNNHORDLAND along the way. Nordhuglo Rubbestad- Sunde Oslo neset S TO R D Ranavik In Austevoll, Bømlo, Etne, Fitjar, Kvinnherad, Stord, Svortland Utåker Leirvik Halsnøy Matre E T N E Sveio and Tysnes, you can choose between long or Skjershlm. B ØMLO Sydnes 48 Moster- Fjellberg Skånevik short day trips. These trips start and end in the same hamn E134 place, so you don’t have to bring your luggage. -

Heraldic Terms

HERALDIC TERMS The following terms, and their definitions, are used in heraldry. Some terms and practices were used in period real-world heraldry only. Some terms and practices are used in modern real-world heraldry only. Other terms and practices are used in SCA heraldry only. Most are used in both real-world and SCA heraldry. All are presented here as an aid to heraldic research and education. A LA CUISSE, A LA QUISE - at the thigh ABAISED, ABAISSÉ, ABASED - a charge or element depicted lower than its normal position ABATEMENTS - marks of disgrace placed on the shield of an offender of the law. There are extreme few records of such being employed, and then only noted in rolls. (As who would display their device if it had an abatement on it?) ABISME - a minor charge in the center of the shield drawn smaller than usual ABOUTÉ - end to end ABOVE - an ambiguous term which should be avoided in blazon. Generally, two charges one of which is above the other on the field can be blazoned better as "in pale an X and a Y" or "an A and in chief a B". See atop, ensigned. ABYSS - a minor charge in the center of the shield drawn smaller than usual ACCOLLÉ - (1) two shields side-by-side, sometimes united by their bottom tips overlapping or being connected to each other by their sides; (2) an animal with a crown, collar or other item around its neck; (3) keys, weapons or other implements placed saltirewise behind the shield in a heraldic display. -

SVR Brosjyre Kart

VERNEOMRÅDA I Setesdal vesthei, Ryfylkeheiane og Frafjordheiane (SVR) E 134 / Rv 13 Røldal Odda / Hardanger Odda / Hardanger Simlebu E 134 13 Røldal Haukeliseter HORDALAND Sandvasshytta E 134 Utåker Åkra ROGALAND Øvre Sand- HORDALAND Haukeli vatnbrakka TELEMARK Vågslid 520 13 Blomstølen Skånevik Breifonn Haukeligrend E 134 Kvanndalen Oslo SAUDA Holmevatn 9 Kvanndalen Storavassbu Holmevassåno VERNEOMRÅDET Fitjarnuten Etne Sauda Roaldkvam Sandvatnet Sæsvatn Løkjelsvatnhytta Saudasjøen Skaulen Nesflaten Varig verna Sloaros Breivatn Bjåen Mindre verneområdeVinje Svandalen n e VERNEOMRÅDAVERNEOVERNEOMRÅDADA I d forvalta av SVR r o Bleskestadmoen E 134 j Dyrskarnuten f a Ferdselsrestriksjonar: d Maldal Hustveitsåta u Lislevatn NR Bråtveit ROGALAND Vidmyr NR Haugesund Sa Suldalsvatnet Olalihytta AUST-AGDER Lundane Heile året Hovden LVO Hylen Jonstøl Hovden Kalving VINDAFJORD (25. april–31. mai) Sandeid 520 Dyrskarnuten Snønuten Hartevatn 1604 TjørnbrotbuTjø b tb Trekk Hylsfjorden (15. april–20. mai) 46 Vinjarnuten 13 Kvilldal Vikedal Steinkilen Ropeid Suldalsosen Sand Saurdal Dyraheio Holmavatnet Urdevasskilen Turisthytter i SVR SULDAL Krossvatn Vindafjorden Vatnedalsvatnet Berdalen Statsskoghytter Grjotdalsneset Stranddalen Berdalsbu Fjellstyrehytter Breiavad Store Urvatn TOKKE 46 Sandsfjorden Sandsa Napen Blåbergåskilen Reinsvatnet Andre hytter Sandsavatnet 9 Marvik Øvre Moen Krokevasskvæven Vindafjorden Vatlandsvåg Lovraeid Oddatjørn- Vassdalstjørn Gullingen dammen Krokevasshytta BYKLE Førrevass- Godebu 13 dammen Byklestøylane Haugesund Hebnes -

NR. 4 September 2020 ÅRGANG 62 Kyrkjeblad for Bjoa, Imsland, Sandeid, Skjold, Vats, Vikebygd, Vikedal Og Ølen

OFFENTLEG INFORMASJON NR. 4 September 2020 ÅRGANG 62 Kyrkjeblad for Bjoa, Imsland, Sandeid, Skjold, Vats, Vikebygd, Vikedal og Ølen Gudsteneste på Romsa, sjå side 6 Kateketen har ordet 2 Springing gjev pusterom! 4 Framleis rom i kyrkja 8 Hausten 2020 2 Bjoa kyrkje 125 år 5 Frå kyrkjeboka 8 Redaksjonspennen 3 Oppgradering av Bjoa kyrkje 5 Gundstenester 10 Tradisjon i 120 år 3 Gudsteneste på Romsa 6 Møte og arrangement 11 Orgelet i Vats kyrkje 100 år 3 Kva er kyrkja? 7 Inspirasjonssamling 12 Konfirmantar Bjoa og Ølen 5 Endeleg søndag på Kårhus 7 1 Redaksjons- Kateketen har ordet Britt Karstensen, kateket. PENNEN Av Steinar Skartland HYRDINGEN: Kyrkjeleg fellesråd har gjennom fleire Ansvarleg: Steinar Skartland år fått ekstra midlar av kommunen Tlf. 908 73 170 Ikkje som planlagt til oppgradering av kyrkjene. Den 8. Epost: [email protected] kyrkja som får gleda av dette er på Bjoa. Bladpengar/gåver til Hyrdingen Det blei plutseleg travelt med haust- Å konfirmera tyder å stadfesta. I Ekstra midlane er redusert vesentleg på konto: 3240.11.17937 og konfirmasjonar i år. Sånn blir det, når konfirmasjonen stadfester Gud gåva i nå, men fellesråd og kyrkjeverje VIPPS nr 53 14 72 ting ikkje går som planlagt. Kanskje dåpen, at me får vera Hans born, at prioriterer bygg og kyrkjegardar så Adr. Skjold kyrkje var det like greitt for nokon, kanskje Han framleis vil vera nær. Sånt sett godt det let seg gjera for å sikra at Kleivavegen 2, 5574 Skjold blei det litt mykje stress for andre, men kan ein nesten seie at me ALLE «blir kyrkjene òg i framtida skal vera tenlege Hans Asbjørn Aasbø talar på ettermiddagsmøtet. -

Pilgrimage Background Notes

Pilgrimage Background Notes Source 1 – Cross Gneth The ‘Cross Gneth’ or ‘Croes Naid’ was a relic said to be a piece of the ‘True Cross’ on which Jesus Christ had died. It had belonged to the native Prince of North Wales and formed part of the spoils given over to Edward I at the close of the campaign against Llewellyn and the Welsh in 1283. The relic was first taken to Westminster Abbey and later in the reign of Edward II it was kept in the Tower of London. Soon after the foundation of the Order of the Garter in about 1348, Edward III gave the cross to the College of St George, Windsor Castle, to be displayed in St George’s Chapel, the spiritual home of the Order. The entry in the 1534 inventory reads: “Item the holy crosse closyd in golde garnyshed with rubyes, saffers hemerods...the fote off this crosse is all golde costyd standing apon lyons garnyshed full with parlle and stone...the whiche holy crosee was at the pryorye off Northeyn Walys and Kyng Edwarde the thyrde owre fyrst fowndar gave the lyvelodde to have this holy crosse to Wyndesore.” It came to be regarded as the Chapel’s chief relic and remained the focus for pilgrimage and devotion for over 200 years. This is reflected in the importance that was placed on it when a new Chapel was built for the Order by Edward IV in the 15th century: the roof boss bearing its image was one of the first bosses to have been completed, in 1480-1481. -

Iconic Hikes in Fjord Norway Photo: Helge Sunde Helge Photo

HIMAKÅNÅ PREIKESTOLEN LANGFOSS PHOTO: TERJE RAKKE TERJE PHOTO: DIFFERENT SPECTACULAR UNIQUE TROLLTUNGA ICONIC HIKES IN FJORD NORWAY PHOTO: HELGE SUNDE HELGE PHOTO: KJERAG TROLLPIKKEN Strandvik TROLLTUNGA Sundal Tyssedal Storebø Ænes 49 Gjerdmundshamn Odda TROLLTUNGA E39 Våge Ølve Bekkjarvik - A TOUGH CHALLENGE Tysnesøy Våge Rosendal 13 10-12 HOURS RETURN Onarheim 48 Skare 28 KILOMETERS (14 KM ONE WAY) / 1,200 METER ASCENT 49 E134 PHOTO: OUTDOORLIFENORWAY.COM PHOTO: DIFFICULTY LEVEL BLACK (EXPERT) Fitjar E134 Husnes Fjæra Trolltunga is one of the most spectacular scenic cliffs in Norway. It is situated in the high mountains, hovering 700 metres above lake Ringe- ICONIC Sunde LANGFOSS Håra dalsvatnet. The hike and the views are breathtaking. The hike is usually Rubbestadneset Åkrafjorden possible to do from mid-June until mid-September. It is a long and Leirvik demanding hike. Consider carefully whether you are in good enough shape Åkra HIKES Bremnes E39 and have the right equipment before setting out. Prepare well and be a LANGFOSS responsible and safe hiker. If you are inexperienced with challenging IN FJORD Skånevik mountain hikes, you should consider to join a guided tour to Trolltunga. Moster Hellandsbygd - A THRILLING WARNING – do not try to hike to Trolltunga in wintertime by your own. NORWAY Etne Sauda 520 WATERFALL Svandal E134 3 HOURS RETURN PHOTO: ESPEN MILLS Ølen Langevåg E39 3,5 KILOMETERS / ALTITUDE 640 METERS Vikebygd DIFFICULTY LEVEL RED (DEMANDING) 520 Sveio The sheer force of the 612-metre-high Langfossen waterfall in Vikedal Åkrafjorden is spellbinding. No wonder that the CNN has listed this 46 Suldalsosen E134 Nedre Vats Sand quintessential Norwegian waterfall as one of the ten most beautiful in the world. -

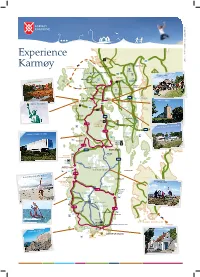

Experience Karmøy

E39 E134 Experience BUS SERVICE TO E134 VANDVIK ØRJAN B. IVERSEN, CAMILLA APPEX.NO / PHOTOS: OSLO, BERGEN, AKSDAL STAVANGER HAUGESUND DYRAFJELLET 172 M.A.S.L Karmøy FAST FERRY: N HAUGESUND - FEØY 20 MIN 9-HOLES HAUSKE GÅRD MINIGOLF 18-HOLES E134 VIKING FARM VISNES MINE AREA KVEITEVIKEN THE FIVE POOR MAIDENS E39 FV47 OLAV’S CHURCH E134 STATUE OF LIBERTY HAUGESUND AIRPORT, E134 KARMØY FV47 HÅVIK HØYEVARDE BUS SERVICE 19 KM K AR TO STAVANGER MØYTUNNELEN AND BERGEN NORDVEGEN HISTORY CENTRE FV47 16 KM Haugalands- KARMØY FISHERY MUSEUM vatnet VEAVÅGEN 12 KM FV47 KOPERVIK ÅKREHAMN COASTAL MUSEUM FV511 ÅKREHAMN 4 KM BEAUTIFUL SILKY BEACHES B SÅLEFJELL PEAK UR MA VE GE BOATHOUSES N AT HOP 8 KM E39 13 KM 8 KM 9-HOLES GREAT SURFING BEACHES FERRY: ARSVÅGEN - MORTAVIKA 20 MIN SKUDENESHAVN JUNGLE PARK STAVANGER HISTORIC SKUDENESHAVN SYRENESET FORT THE MUSEUM IN MÆLANDSGÅRDEN SKUDENESHAVN VIKEHOLMEN GEITUNGEN SIGHTSEEING HIKING AND BIKING TRAILS ACCOMMODATION COMMUNICATIONS Avaldsnes Viking Farm. Follow in the foot- The Karmøy countryside is attractive and diverse Park Inn, Haugesund Airport Hotel Airlines steps of the ancient kings through the historic with many opportunities to get outdoors and Helganesveien 24, 4262 Avaldsnes RyanAir: T: +47 52 85 78 00, www.ryanair.com landscape at Avaldsnes. Bukkøy island features be active or simply relax: T: +47 52 86 10 90 Norwegian: T: +47 815 21 815, www.norwegian.no many reconstructed Viking buildings. Meet www.haugalandet.friskifriluft.no E-mail: [email protected] SAS: T: +47 05400, www.sas.no Vikings for activities and tours in the summer www.parkinnhotell.no/hotell-haugesund Widerøe: T: +47 810 01 200, www.wideroe.no season. -

Vestlandskjeler, Velstand Og Makt.Pdf (545.2Kb)

AmS-Varia 31 Vestlandskjeler, velstand og makt. Tre studier av Vestlandskjelenes plass og betydning i lokalsamfunnet i eldre jernalder i Vest-Norge. ÅSA DAHLIN HAUKEN Hauken, Å. Dahlin 1997: Westland cauldrons, wealth and power. Three studies on the rôle and significance of Westland Cauldrons in the Early Iron Age local community in Western Norwaway. Ams-Varia 31, 37-52. Stavanger. ISSN 0332-6306, ISBN 82-7760-030-5, UDK 903.23(481.5)”6383”. All Roman Iron Age and Migration Period graves in three West Norwegian districts were analysed and compared from a quantitative and qualitative aspect. Cauldron graves in general belong to an upper stratum of graves, not always quantitatively, but qualitatively. Rich graves are also associated with the best farms in each district. Graves with Westland cauldrons are never found on small, poor farms. The rich graves are not evenly distributed through time, and are not found exclusively on the same farm through the period studied. The changes in both time and space are seen as result of an internal competition for power in an unstable society. Rich graves are interpreted as a part of a strategy to preserve or enhance social positions. Åsa Dahlin Hauken, Arkeologisk Museum i Stavanger, Box 487, N-4001 STAVANGER, NORWAY. Telephone: (+47) 51846000. Fax: (+47) 51846199. Denne artikkelen er en bearbeidet og forkortet versjon av De såkalte vestlandskjelene er den numerært største en del av et kapittel i min magistergradsavhandling om gruppen av det arkeologene benevner romersk import i vestlandskjelene (Hauken 1984: 122 ff). I kapitlet ble Norge. Vestlandskjelen er et kar av bronse, omtrent 30 vestlandskjelene analyserte dels som gruppe og sammen- cm i munningsdiameter og 15-18 cm høyt.