Updated Meeting Posting Warning

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

General Notice Letter (Gnl) Response

RUBIN AND RUDMAN LLP COUNSELLORS AT LAW 50 ROWES WHARF • BOSTON, MASSACHUSETTS 02110-3319 TELEPHONE: (6i7)330-7000 • FACSIMILE: (617)4-39-9556 • EMAIL: [email protected] Margaret Van Deusen Direct Dial: (617) 330-7154 E-mail: [email protected] June 26, 2000 BY MESSENGER Richard Haworth United States Environmental Protection Agency Site Evaluation and Response Section II 1 Congress Street Suite 1100 Mail Code HBR Boston, Massachusetts 02114-2023 Re: EPA Notice Letter, Old Colony Railroad Site, East Bridgewater, MA Dear Mr. Haworth: This firm is counsel to the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority ("MBTA") with respect to the above matter. By letter dated June 5, 2000, the United States Environmental Protection Agency ("EPA") notified the MBTA of its potential liability regarding the Old Colony Railroad Site in East Bridgewater, MA ("Site") pursuant to the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation and Liability Act ("CERCLA"), 42 U.S.C. § 9607(a). The letter also informed the MBTA that EPA plans to conduct immediate removal activities involving installation of a perimeter fence, elimination of direct contact with contaminated soils and prevention of off-site migration via soil transport. EPA is asking the MBTA to perform or to finance these activities. Pursuant to conversations with Marcia Lamel, Senior Enforcement Counsel, EPA, the MBTA was given until today to respond to EPA's letter. As discussed below, even though the MBTA does not believe that it is a responsible party at this Site, it is willing to participate in fencing the perimeter of the Site and posting signage. The MBTA is also willing to discuss with EPA covering "hot spots" of contaminated soil on the Site with some sort of synthetic cover. -

The Founders of the Woodstock Artists Association a Portfolio

The Founders of the Woodstock Artists Association A Portfolio Woodstock Artists Association Gallery, c. 1920s. Courtesy W.A.A. Archives. Photo: Stowall Studio. Carl Eric Lindin (1869-1942), In the Ojai, 1916. Oil on Board, 73/4 x 93/4. From the Collection of the Woodstock Library Association, gift of Judy Lund and Theodore Wassmer. Photo: Benson Caswell. Henry Lee McFee (1886- 1953), Glass Jar with Summer Squash, 1919. Oil on Canvas, 24 x 20. Woodstock Artists Association Permanent Collection, gift of Susan Braun. Photo: John Kleinhans. Andrew Dasburg (1827-1979), Adobe Village, c. 1926. Oil on Canvas, 19 ~ x 23 ~ . Private Collection. Photo: Benson Caswell. John F. Carlson (1875-1945), Autumn in the Hills, 1927. Oil on Canvas, 30 x 60. 'Geenwich Art Gallery, Greenwich, Connecticut. Photo: John Kleinhans. Frank Swift Chase (1886-1958), Catskills at Woodstock, c. 1928. Oil on Canvas, 22 ~ x 28. Morgan Anderson Consulting, N.Y.C. Photo: Benson Caswell. The Founders of the Woodstock Artists Association Tom Wolf The Woodstock Artists Association has been showing the work of artists from the Woodstock area for eighty years. At its inception, many people helped in the work involved: creating a corporation, erecting a building, and develop ing an exhibition program. But traditionally five painters are given credit for the actual founding of the organization: John Carlson, Frank Swift Chase, Andrew Dasburg, Carl Eric Lindin, and Henry Lee McFee. The practice of singling out these five from all who participated reflects their extensive activity on behalf of the project, and it descends from the writer Richard Le Gallienne. -

The Finding Aid to the Alf Evers Archive

FINDING AID TO THE ALF EVERS’ ARCHIVE A Account books & Ledgers Ledger, dark brown with leather-bound spine, 13 ¼ x 8 ½”: in front, 15 pp. of minutes in pen & ink of meetings of officers of Oriental Manufacturing Co., Ltd., dating from 8/9/1898 to 9/15/1899, from its incorporation to the company’s sale; in back, 42 pp. in pencil, lists of proverbs; also 2 pages of proverbs in pencil following the minutes Notebook, 7 ½ x 6”, sold by C.W. & R.A. Chipp, Kingston, N.Y.: 20 pp. of charges & payments for goods, 1841-52 (fragile) 20 unbound pages, 6 x 4”, c. 1837, Bastion Place(?), listing of charges, payments by patrons (Jacob Bonesteel, William Britt, Andrew Britt, Nicolas Britt, George Eighmey, William H. Hendricks, Shultis mentioned) Ledger, tan leather- bound, 6 ¾ x 4”, labeled “Kingston Route”, c. 1866: misc. scattered notations Notebook with ledger entries, brown cardboard, 8 x 6 ¼”, missing back cover, names & charges throughout; page 1 has pasted illustration over entries, pp. 6-7 pasted paragraphs & poems, p. 6 from back, pasted prayer; p. 23 from back, pasted poems, pp. 34-35 from back, pasted story, “The Departed,” 1831-c.1842 Notebook, cat. no. 2004.001.0937/2036, 5 1/8 x 3 ¼”, inscr. back of front cover “March 13, 1885, Charles Hoyt’s book”(?) (only a few pages have entries; appear to be personal financial entries) Accounts – Shops & Stores – see file under Glass-making c. 1853 Adams, Arthur G., letter, 1973 Adirondack Mountains Advertisements Alderfer, Doug and Judy Alexander, William, 1726-1783 Altenau, H., see Saugerties, Population History files American Revolution Typescript by AE: list of Woodstock residents who served in armed forces during the Revolution & lived in Woodstock before and after the Revolution Photocopy, “Three Cemeteries of the Wynkoop Family,” N.Y. -

Technical Memorandum Bruce Freeman Rail Trail Concord, MA

Technical Memorandum Bruce Freeman Rail Trail Concord, MA Cultural Resources Survey January 10, 2008 Submitted to: Vanasse Hangen Brustlin, Inc. 530 Broadway Providence, Rhode Island 02909 Introduction The Town of Concord, Massachusetts has contracted with Vanasse Hangen Brustlin, Inc. (VHB) for professional design and engineering services for a non-motorized multi-use recreational path/rail trail over the 3.5 mile section of the proposed Bruce Freeman Rail Trail from the southerly side of Route 2 south to the Sudbury town line (Figure 1). The design and engineering services include a survey and documentation of the historic resources along the proposed trail alignment. PAL entered into a Subconsultant Contract with VHB for the historic resources survey and documentation. The survey’s purpose is to identify historic railroad-related resources along the rail corridor, to document these resources in writing and with photographs, and to provide recommendations for incorporating existing railroad infrastructure in and creating educational opportunities along the rail corridor. This technical memorandum describes the field and research methodologies employed by PAL in conducting fieldwork and archival research, presents the results of the field survey, and provides recommendations for the integration of railroad-related resources into the landscape design and interpretive programming elements of the finished rail trail. Methodology PAL employees John Daly (industrial historian) and Quinn Stuart (architectural assistant) completed a site walk of the 3.5-mile proposed rail trail corridor on August 23, 2007. Prior to the site walk, PAL employees met representatives of the Town of Concord to discuss priorities for the survey. Valarie Kinkade of the Concord Historical Commission, Ashley Galvin of the Concord Historic District Commission, and Henry T. -

Invests$'Jlom Into Restoring Railroadservice

Paga46 • August2015 26, • www.oonotructlonoquipmenlgUlcle.com • CONSTRUCTION EQUIPMEriTGUIIE � Invests$'JlOM Into Restoring Railroad Service ByJay Adams problems. While the Commonwealth of CEO CORRESPONDENT Cardi Corp. crews work 011 rat/over Massachusetts provided an emergency sub PresidentAve1n1e tn FaU Rive,: sidy to continue service to tl1e Soud1 Coast in A long-dead mode of transportation is 1958, it was not enough. Passenger service coming back to life in several cities in on the Old Colony line was abandooed in Massachusetts.. 1959, with the exception of the main line Months of summer work have begun to between Boston and Providence,R.l. repair vital rail bridgesin the FallRiver area, The currentone-year phase of lhe project partof the 120-month South Coast Rail proj is seeingrailways shoredup forthe firsttime ect d1at is restoring52 mi. (83.6 km)of com in 56 years. muter rail service between Boston and lhe With the first year design phase complete. Massachusetts South Coast. The entirecost involving state discussions with communi of die decade-long plan is estimated to be tiesfrom Stoughton to FallRiver. tons of soil $2l0million. samples are being taken over many months "We are thrilled about the three Fall River to discerntoxic conte111 and other vital infor bridges and the Warnsutta Bridge in New mation. When the design phase is complete Bedford. These are solid investments that and the samples in hand, MassDOT will will provide immediate benefit to the begin replacing four bridges - New expanding freightrail sector. along the same Bedford's Wan�utta Bridge. Fall River's route as lhe future South Coast Rail com Golf Club Road. -

Visit Saugerties

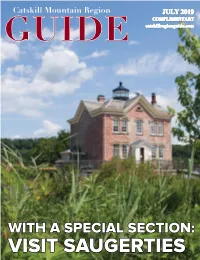

Catskill Mountain Region JULY 2019 COMPLIMENTARY GUIDE catskillregionguide.com WITH A SPECIAL SECTION: VISIT SAUGERTIES July 2019 • GUIDE 1 2 • www.catskillregionguide.com www.catskillregionguide.com IN THIS ISSUE VOLUME 34, NUMBER 7 July 2019 PUBLISHERS Peter Finn, Chairman, Catskill Mountain Foundation Sarah Finn, President, Catskill Mountain Foundation EDITORIAL DIRECTOR, CATSKILL MOUNTAIN FOUNDATION Sarah Taft ADVERTISING SALES Barbara Cobb Steve Friedman CONTRIBUTING WRITERS Simona David, EA Murphy, Garan Santicola, Jeff Senterman, Laura Taylor, Margaret Donsbach Tomlinson, Robert Tomlinson ADMINISTRATION & FINANCE Candy McKee Justin McGowan & Isabel Cunha On the cover: The Saugerties Lighthouse. Photo courtesy iStock.com/Nancy Kennedy PRINTING Catskill Mountain Printing Services 4 THE ARTS DISTRIBUTION Catskill Mountain Foundation 10 ARTS LEADER: Nancy Barton, Prattsville Arts Center By Robert Tomlinson EDITORIAL DEADLINE FOR NEXT ISSUE: July 10 12 TRI-COUNTY BEAUTY AT THE GILBOA MUSEUM The Catskill Mountain Region Guide is published 12 times a year by the Catskill Mountain Foundation, Inc., Main Street, PO Box By Garan Santicola 924, Hunter, NY 12442. If you have events or programs that you would like to have covered, please send them by e-mail to tafts@ catskillmtn.org. Please be sure to furnish a contact name and in- 16 SPECIAL SECTION: VISIT SAUGERTIES clude your address, telephone, fax, and e-mail information on all correspondence. For editorial and photo submission guidelines send a request via e-mail to [email protected]. The liability of the publisher for any error for which it may be 26 ART IS AT HOME IN THE CATSKILL MOUNTAINS held legally responsible will not exceed the cost of space ordered By Simona David or occupied by the error. -

Northeast Corridor New York to Philadelphia

Northeast Corridor New York to Philadelphia 1 INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................2 2 A HISTORY..............................................................................................3 3 ROLLING STOCK......................................................................................4 3.1 EMD AEM-7 Electric Locomotive .......................................................................................4 3.2 Amtrak Amfleet Coaches .................................................................................................5 4 SCENARIOS.............................................................................................6 4.1 Go Newark....................................................................................................................6 4.2 New Jersey Trenton .......................................................................................................6 4.3 Spirit or Transportation ..................................................................................................6 4.4 The Big Apple................................................................................................................6 4.5 Early Clocker.................................................................................................................7 4.6 Evening Clocker.............................................................................................................7 4.7 Northeast Regional ........................................................................................................7 -

Encyklopédia Kresťanského Umenia

Marie Žúborová - Němcová: Encyklopédia kresťanského umenia americká architektúra - pozri chicagská škola, prériová škola, organická architektúra, Queen Anne style v Spojených štátoch, Usonia americká ilustrácia - pozri zlatý vek americkej ilustrácie americká retuš - retuš americká americká ruleta/americké zrnidlo - oceľové ozubené koliesko na zahnutej ose, užívané na zazrnenie plochy kovového štočku; plocha spracovaná do čiarok, pravidelných aj nepravidelných zŕn nedosahuje kvality plochy spracovanej kolískou americká scéna - american scene americké architektky - pozri americkí architekti http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:American_women_architects americké sklo - secesné výrobky z krištáľového skla od Luisa Comforta Tiffaniho, ktoré silno ovplyvnili európsku sklársku produkciu; vyznačujú sa jemnou farebnou škálou a novými tvarmi americké litografky - pozri americkí litografi http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:American_women_printmakers A Anne Appleby Dotty Atti Alicia Austin B Peggy Bacon Belle Baranceanu Santa Barraza Jennifer Bartlett Virginia Berresford Camille Billops Isabel Bishop Lee Bontec Kate Borcherding Hilary Brace C Allie máj "AM" Carpenter Mary Cassatt Vija Celminš Irene Chan Amelia R. Coats Susan Crile D Janet Doubí Erickson Dale DeArmond Margaret Dobson E Ronnie Elliott Maria Epes F Frances Foy Juliette mája Fraser Edith Frohock G Wanda Gag Esther Gentle Heslo AMERICKÁ - AMES Strana 1 z 152 Marie Žúborová - Němcová: Encyklopédia kresťanského umenia Charlotte Gilbertson Anne Goldthwaite Blanche Grambs H Ellen Day -

Standard Metal for LOCOMOTIVE WEARING PARTS

AUGUST, 1909 .~;, Railroad - Dep~rtm(n-l ,. .: ~:- .· , . y. JV\. (. A. , .. BUILDERS' HARDWARE ABSOLUTELY EUROPEAN FIREF;tOOF TH£ PLAN ~o't'EL Ess~~ For every need and of the highest BOSTON quality in every class New Britain, Conn. DIRECTLY OPPOSITE THE SOUTH STATION CONVENIENT TO BUSINESSCENTii:RB AND RUBLIC INSTITUTIONS ACCOMMODATIONS, CATERING AND OUR HOME DOOR CHECK SERVICE UNSURPASSED is the only appliance of its kind that with WRITE FOR BOOKLET. stands the hard use of railway service. 1-- ~ - ' . PINT~Cn LltiHT (LfCTRIC LltiHT Car Lighting by the PINT~cn Axle Driven Dqnomo~y~tem ~ \'~ Tf)1 with perfected -;iO of electric lighting. l:quip gle mantle lamp~. ment~ either ~old or oper Co~t-Ooe cent per hour. ated under contract. , ~T(A~ HfAT Car Heating by controllable direct steam and water circulating systems, steam tight couplers, traps, train pipe valves and other appliances. Thermo- Jet System where pressure is not desired. , SAF.ETY CAR HEATING & LIGHTING COMPANY,.. 2 RECTOR STREET, NEW YORK ,- Chicago Philadelphia St. Louis Boston Berkeley, Cal. Atlanta Montreal I T - ' 1Rew lJlorlit 1Rew lba"en anb lbartforb 1Railroab 1Rews. VoL. XII NEW HAVEN, CONN., AUGUST, 1909 No. 10 Train Service To_ The Boats. Brockton) anrl :\liddleboro to the "new road" (just completed under title of Dighton & "Old Colony Passenger Station. Fall River Line to New York" was the way the big signs Somerset) through Randolph and Taunton. used to read which hung for years on either The following in regard to the steamboat train over the "new road" and a description side of the Old Colony Depot at the corner of the towns through which it passed is taken of South and Kneeland streets in Boston. -

Transportation in Bridgewater, 1900-1910 Benjamin A

Bridgewater State University Virtual Commons - Bridgewater State University Bridgewater, Massachusetts: A oT wn in Transition Local History 2009 Transportation in Bridgewater, 1900-1910 Benjamin A. Spence Recommended Citation Spence, Benjamin A. (2009). Transportation in Bridgewater, 1900-1910. In Bridgewater, Massachusetts: A oT wn in Transition. Monograph 2. Available at: http://vc.bridgew.edu/spence/2 This item is available as part of Virtual Commons, the open-access institutional repository of Bridgewater State University, Bridgewater, Massachusetts. Bridgewater, Massachusetts A Town in Transition Transportation 1900-1910 (Including Extensive Historical Background) Dr. Benjamin A. Spence © 2009 An Explanation For several years I have had the pleasure of delving into the history of Bridgewater, Massachusetts, concentrating on the first quarter of the twentieth century and providing, when appropriate, historical background to make my discussions clearer. Although my research and writing are ongoing, I have decided to make available drafts of a number of topics which I have explored at length, with the hope that the material presented will prove helpful to many readers. I would request that credit be given if my findings are used by other writers or those making oral presentations. As my study has proceeded, many people have been helpful and, hopefully, I will be able to thank all of them during the course of my writing. At this point, let me mention just a few who have been especially supportive. Many thanks to the Trustees of Bridgewater’s Public Library for allowing me free access to the sources in the town’s library, made easier by the aid given to me by the research librarians under the competent direction of Mary O’Connell. -

Saturday Night Live

return to updates Saturday Night “Jive” by “Kevin” Since its inception in 1975, “SNL” has launched the careers of many of the brightest comedy performers of their generation. As the New York Times noted on the occasion of the show’s Emmy-winning 25th anniversary special in 1999, “in defiance of both time and show business convention, ‘SNL’ is still the most pervasive influence on the art of comedy in contemporary culture” This paper is an attempt to discover the players behind this “pervasive influence”. This is an opinion piece compiled with information readily available from an array of internet sources. In the beginning, there was… (wikipedia) In 1974, NBC Tonight Show host Johnny Carson requested that the weekend broadcasts of “Best of Carson” come to an end. To fill in the gap, the network brought in Dick Ebersol – a protege of legendary ABC Sports president Roone Arledge – to develop a 90-minute late-night variety show. Ebersol’s first order of business was hiring a young Canadian producer named Lorne Michaels. There’s the starting gun. Let the search for red flags begin. (wikipedia) Duncan “Dick” Ebersol (born July 28, 1947) was born in Torrington, Connecticut. The son of Mary (nee) Duncan and Charles Roberts Ebersol, a former chairman of the American Cancer Society. He and Josiah Bunting III are half-brothers. In 1975, Ebersol and Lorne Michaels conceived of and developed Saturday Night Live. Named as Vice President of Late Night Programming at age 28... NBC’s first-ever vice president under the age of 30. Editor: In 1983, Ebersol formed No Sleep Productions, an independent production company that created Emmy Award-winning NBC shows Friday Night Videos and Later with Bob Costas. -

Chapter XIX. Custom House. Post Office. Public Utilities

Chapter XIX CUSTOM HOUSE POST OFFICE PUBLIC UTILITIES Custom House Soon after the Revolution the Federal Government established the first custom house, in what was known as the Dighton District . It was near the shore of Taunton Estuary, just south of Muddy Cove . The Fall River District replaced the Dighton District in 1837 and the custom house wa s located in the town hall on Central Street . When the new town hall was built, it was located there for a few years and then moved to the secon d floor of a building at the northeast corner of Anawan and Water Streets , where it remained until a Federal building was erected on Bedford Stree t in 1880. Post Office The first general issue of postage stamps by the United States was i n 1847. Stamps were used before that time in some localities but were issue d at the expense of the postmasters . The price of letter postage was accord- ing to the number of sheets used ; consequently letters were written on large sheets, then folded and sealed, leaving a space for the address. Envelopes and blotting paper did not come into general use until 1845 . The first mail was handled in Fall River, then Troy, in 1811 . Charles Pitman was the first postmaster ; at first located in the village, he moved his post office to Steep Brook in 1813.1 W. W. Howes, First Assistant Postmaster General reports that th e first United States Post Office was "established in Fall River, Massachu- setts, on March 14, 1816 . The first Postmaster was Abraham Bowen.