Wildlife Action Plan: Dry Northern Forest Pine Barrens

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Natural Communities of Michigan: Classification and Description

Natural Communities of Michigan: Classification and Description Prepared by: Michael A. Kost, Dennis A. Albert, Joshua G. Cohen, Bradford S. Slaughter, Rebecca K. Schillo, Christopher R. Weber, and Kim A. Chapman Michigan Natural Features Inventory P.O. Box 13036 Lansing, MI 48901-3036 For: Michigan Department of Natural Resources Wildlife Division and Forest, Mineral and Fire Management Division September 30, 2007 Report Number 2007-21 Version 1.2 Last Updated: July 9, 2010 Suggested Citation: Kost, M.A., D.A. Albert, J.G. Cohen, B.S. Slaughter, R.K. Schillo, C.R. Weber, and K.A. Chapman. 2007. Natural Communities of Michigan: Classification and Description. Michigan Natural Features Inventory, Report Number 2007-21, Lansing, MI. 314 pp. Copyright 2007 Michigan State University Board of Trustees. Michigan State University Extension programs and materials are open to all without regard to race, color, national origin, gender, religion, age, disability, political beliefs, sexual orientation, marital status or family status. Cover photos: Top left, Dry Sand Prairie at Indian Lake, Newaygo County (M. Kost); top right, Limestone Bedrock Lakeshore, Summer Island, Delta County (J. Cohen); lower left, Muskeg, Luce County (J. Cohen); and lower right, Mesic Northern Forest as a matrix natural community, Porcupine Mountains Wilderness State Park, Ontonagon County (M. Kost). Acknowledgements We thank the Michigan Department of Natural Resources Wildlife Division and Forest, Mineral, and Fire Management Division for funding this effort to classify and describe the natural communities of Michigan. This work relied heavily on data collected by many present and former Michigan Natural Features Inventory (MNFI) field scientists and collaborators, including members of the Michigan Natural Areas Council. -

Northern Fen Communitynorthern Abstract Fen, Page 1

Northern Fen CommunityNorthern Abstract Fen, Page 1 Community Range Prevalent or likely prevalent Infrequent or likely infrequent Absent or likely absent Photo by Joshua G. Cohen Overview: Northern fen is a sedge- and rush-dominated 8,000 years. Expansion of peatlands likely occurred wetland occurring on neutral to moderately alkaline following climatic cooling, approximately 5,000 years saturated peat and/or marl influenced by groundwater ago (Heinselman 1970, Boelter and Verry 1977, Riley rich in calcium and magnesium carbonates. The 1989). community occurs north of the climatic tension zone and is found primarily where calcareous bedrock Several other natural peatland communities also underlies a thin mantle of glacial drift on flat areas or occur in Michigan and can be distinguished from shallow depressions of glacial outwash and glacial minerotrophic (nutrient-rich) northern fens, based on lakeplains and also in kettle depressions on pitted comparisons of nutrient levels, flora, canopy closure, outwash and moraines. distribution, landscape context, and groundwater influence (Kost et al. 2007). Northern fen is dominated Global and State Rank: G3G5/S3 by sedges, rushes, and grasses (Mitsch and Gosselink 2000). Additional open wetlands occurring on organic Range: Northern fen is a peatland type of glaciated soils include coastal fen, poor fen, prairie fen, bog, landscapes of the northern Great Lakes region, ranging intermittent wetland, and northern wet meadow. Bogs, from Michigan west to Minnesota and northward peat-covered wetlands raised above the surrounding into central Canada (Ontario, Manitoba, and Quebec) groundwater by an accumulation of peat, receive inputs (Gignac et al. 2000, Faber-Langendoen 2001, Amon of nutrients and water primarily from precipitation et al. -

Species at Risk on Department of Defense Installations

Species at Risk on Department of Defense Installations Revised Report and Documentation Prepared for: Department of Defense U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Submitted by: January 2004 Species at Risk on Department of Defense Installations: Revised Report and Documentation CONTENTS 1.0 Executive Summary..........................................................................................iii 2.0 Introduction – Project Description................................................................. 1 3.0 Methods ................................................................................................................ 3 3.1 NatureServe Data................................................................................................ 3 3.2 DOD Installations............................................................................................... 5 3.3 Species at Risk .................................................................................................... 6 4.0 Results................................................................................................................... 8 4.1 Nationwide Assessment of Species at Risk on DOD Installations..................... 8 4.2 Assessment of Species at Risk by Military Service.......................................... 13 4.3 Assessment of Species at Risk on Installations ................................................ 15 5.0 Conclusion and Management Recommendations.................................... 22 6.0 Future Directions............................................................................................. -

Butterflies of North Carolina - Twenty-Eighth Approximation 159

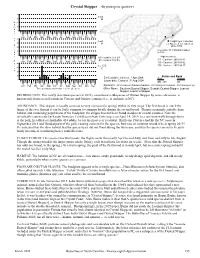

Crystal Skipper Atrytonopsis quinteri 40 n=0 30 M N 20 u m 10 b e 0 r 5 25 15 5 25 15 5 25 15 5 25 15 5 25 15 5 25 15 15 5 25 15 5 25 15 5 25 15 5 25 15 5 25 15 5 25 Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec • o 40 • f n=0 = Sighting or Collection 30 P x• = Not seen nor collected F since 1980 l 20 i 5 records / 32 individuals added g 10 to 28th h 0 t 5 25 15 5 25 15 5 25 15 5 25 15 5 25 15 5 25 15 NC counties: 2 or 2% High counts of: 15 5 25 15 5 25 15 5 25 15 5 25 15 5 25 15 5 25 SC counties: 0 or 0% 414 - Carteret - 2019-04-14 D Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec a 40 100 - Carteret - 2001-05-02 t n=123 100 - Carteret - 2003-04-17 e 30 C s 20 10 Status and Rank Earliest date: Carteret 1 Apr 2008 State Global 0 Latest date: Carteret 31 Aug 2004 5 25 15 5 25 15 5 25 15 5 25 15 5 25 15 5 25 15 SR - S1 G1 15 5 25 15 5 25 15 5 25 15 5 25 15 5 25 15 5 25 Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec Synonym: Atrytonopsis hianna loammi, Atrytonopsis loammi, Atrytonopsis sp. -

Native Grasses Benefit Butterflies and Moths Diane M

AFNR HORTICULTURAL SCIENCE Native Grasses Benefit Butterflies and Moths Diane M. Narem and Mary H. Meyer more than three plant families (Bernays & NATIVE GRASSES AND LEPIDOPTERA Graham 1988). Native grasses are low maintenance, drought Studies in agricultural and urban landscapes tolerant plants that provide benefits to the have shown that patches with greater landscape, including minimizing soil erosion richness of native species had higher and increasing organic matter. Native grasses richness and abundance of butterflies (Ries also provide food and shelter for numerous et al. 2001; Collinge et al. 2003) and butterfly species of butterfly and moth larvae. These and moth larvae (Burghardt et al. 2008). caterpillars use the grasses in a variety of ways. Some species feed on them by boring into the stem, mining the inside of a leaf, or IMPORTANCE OF LEPIDOPTERA building a shelter using grass leaves and silk. Lepidoptera are an important part of the ecosystem: They are an important food source for rodents, bats, birds (particularly young birds), spiders and other insects They are pollinators of wild ecosystems. Terms: Lepidoptera - Order of insects that includes moths and butterflies Dakota skipper shelter in prairie dropseed plant literature review – a scholarly paper that IMPORTANT OF NATIVE PLANTS summarizes the current knowledge of a particular topic. Native plant species support more native graminoid – herbaceous plant with a grass-like Lepidoptera species as host and food plants morphology, includes grasses, sedges, and rushes than exotic plant species. This is partially due to the host-specificity of many species richness - the number of different species Lepidoptera that have evolved to feed on represented in an ecological community, certain species, genus, or families of plants. -

Michigan Karner Blue Butterfly HCP

DRAFT MICHIGAN KARNER BLUE BUTTERFLY HABITAT CONSERVATION PLAN Photograph by Jennifer Kleitch ATU F N RA O L T R Printed by Authority of: P.A. 451 of 1994 N E Michigan Department of Natural Resources E S Total Number of Copies Printed: .........XX M O T U Cost per Copy:.................................$XXX R R Wildlife Division Report No. _____ C A P Total Cost: ......................................$XXX DNR E E S D _____ 2007 Michigan Department of Natural Resources M ICHIG AN ICXXXXX (XXXXXX) DRAFT – November 2, 2007 2 DRAFT MICHIGAN KARNER BLUE BUTTERFLY HABITAT CONSERVATION PLAN Prepared by: Michigan Department of Natural Resources Wildlife Division Stevens T. Mason Building P.O. Box 30180 Lansing, MI 48909 Submitted to: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service East Lansing Field Office 2651 Coolidge Road, Suite 101 East Lansing, Michigan 48823 November 2, 2007 DRAFT – November 2, 2007 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The Michigan Department of Natural Resources appreciates the valuable contributions made by many agencies, organizations and individuals during the development of this plan. In particular, we thank the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service for providing funding and technical support. We also thank the members of the Karner Blue Butterfly Working Group and the Karner Blue Butterfly Management Partners Workgroup, who shared important perspectives and expertise during their meetings and document reviews. Finally, we thank the members of the public who helped shape the content of this plan by offering input during public meetings and public- comment periods. A contribution of the Cooperative Endangered Species Conservation Fund Grants Program, Michigan Project E-3-HP Equal Rights for Natural Resource Users The Michigan Department of Natural Resources (MDNR) provides equal opportunities for employment and access to Michigan’s natural resources. -

Oak-Pine Barrens Community Abstract

Oak-Pine Barrens Community Abstract Historical Range Photo by Patrick J. Comer Prevalent or likely prevalent Infrequent or likely infrequent Absent or likely absent Global and State Rank: G3/S2 0.3% of the state’s surface area (Comer et al. 1995). Most of this acreage was concentrated in Newaygo Range: Barrens and prairie communities reached their County (17% or 19,000 acres), Crawford County (15% maximum extent in Michigan approximately 4,000- or 17,000 acres) and Allegan County (14% or 15,000 6,000 years before present, when post-glacial climatic acres). Today merely a few hundred acres of high conditions were comparatively warm and dry. Dur- quality oak-pine barrens remain in Michigan. This rare ing this time, xerothermic conditions allowed for the community constitutes less than 0.005% of the present invasion of fire-dependent, xeric vegetation types into a vegetation, a sixty-fold reduction from the amount of large portion of the Lower Peninsula and into sections oak-pine barrens originally present. of the Upper Peninsula. With the subsequent shift of more mesic climatic conditions southward, there has Currently a few small remnants of oak-pine barrens been a recolonization of mesic vegetation throughout persist. Destructive timber exploitation of pines Michigan. The distribution of fire-dominated com- (1890s) and oaks (1920s) combined with post-logging munities, such as oak-pine barrens, has been reduced slash fires destroyed or degraded oak-pine barrens to isolated patches typically along the climatic tension across Michigan (Michigan Natural Features Inventory zone (Hauser 1953 in Lohrentz and Mattei 1995). In 1995). -

Rare Animals Tracking List

Louisiana's Animal Species of Greatest Conservation Need (SGCN) ‐ Rare, Threatened, and Endangered Animals ‐ 2020 MOLLUSKS Common Name Scientific Name G‐Rank S‐Rank Federal Status State Status Mucket Actinonaias ligamentina G5 S1 Rayed Creekshell Anodontoides radiatus G3 S2 Western Fanshell Cyprogenia aberti G2G3Q SH Butterfly Ellipsaria lineolata G4G5 S1 Elephant‐ear Elliptio crassidens G5 S3 Spike Elliptio dilatata G5 S2S3 Texas Pigtoe Fusconaia askewi G2G3 S3 Ebonyshell Fusconaia ebena G4G5 S3 Round Pearlshell Glebula rotundata G4G5 S4 Pink Mucket Lampsilis abrupta G2 S1 Endangered Endangered Plain Pocketbook Lampsilis cardium G5 S1 Southern Pocketbook Lampsilis ornata G5 S3 Sandbank Pocketbook Lampsilis satura G2 S2 Fatmucket Lampsilis siliquoidea G5 S2 White Heelsplitter Lasmigona complanata G5 S1 Black Sandshell Ligumia recta G4G5 S1 Louisiana Pearlshell Margaritifera hembeli G1 S1 Threatened Threatened Southern Hickorynut Obovaria jacksoniana G2 S1S2 Hickorynut Obovaria olivaria G4 S1 Alabama Hickorynut Obovaria unicolor G3 S1 Mississippi Pigtoe Pleurobema beadleianum G3 S2 Louisiana Pigtoe Pleurobema riddellii G1G2 S1S2 Pyramid Pigtoe Pleurobema rubrum G2G3 S2 Texas Heelsplitter Potamilus amphichaenus G1G2 SH Fat Pocketbook Potamilus capax G2 S1 Endangered Endangered Inflated Heelsplitter Potamilus inflatus G1G2Q S1 Threatened Threatened Ouachita Kidneyshell Ptychobranchus occidentalis G3G4 S1 Rabbitsfoot Quadrula cylindrica G3G4 S1 Threatened Threatened Monkeyface Quadrula metanevra G4 S1 Southern Creekmussel Strophitus subvexus -

A SKELETON CHECKLIST of the BUTTERFLIES of the UNITED STATES and CANADA Preparatory to Publication of the Catalogue Jonathan P

A SKELETON CHECKLIST OF THE BUTTERFLIES OF THE UNITED STATES AND CANADA Preparatory to publication of the Catalogue © Jonathan P. Pelham August 2006 Superfamily HESPERIOIDEA Latreille, 1809 Family Hesperiidae Latreille, 1809 Subfamily Eudaminae Mabille, 1877 PHOCIDES Hübner, [1819] = Erycides Hübner, [1819] = Dysenius Scudder, 1872 *1. Phocides pigmalion (Cramer, 1779) = tenuistriga Mabille & Boullet, 1912 a. Phocides pigmalion okeechobee (Worthington, 1881) 2. Phocides belus (Godman and Salvin, 1890) *3. Phocides polybius (Fabricius, 1793) =‡palemon (Cramer, 1777) Homonym = cruentus Hübner, [1819] = palaemonides Röber, 1925 = ab. ‡"gunderi" R. C. Williams & Bell, 1931 a. Phocides polybius lilea (Reakirt, [1867]) = albicilla (Herrich-Schäffer, 1869) = socius (Butler & Druce, 1872) =‡cruentus (Scudder, 1872) Homonym = sanguinea (Scudder, 1872) = imbreus (Plötz, 1879) = spurius (Mabille, 1880) = decolor (Mabille, 1880) = albiciliata Röber, 1925 PROTEIDES Hübner, [1819] = Dicranaspis Mabille, [1879] 4. Proteides mercurius (Fabricius, 1787) a. Proteides mercurius mercurius (Fabricius, 1787) =‡idas (Cramer, 1779) Homonym b. Proteides mercurius sanantonio (Lucas, 1857) EPARGYREUS Hübner, [1819] = Eridamus Burmeister, 1875 5. Epargyreus zestos (Geyer, 1832) a. Epargyreus zestos zestos (Geyer, 1832) = oberon (Worthington, 1881) = arsaces Mabille, 1903 6. Epargyreus clarus (Cramer, 1775) a. Epargyreus clarus clarus (Cramer, 1775) =‡tityrus (Fabricius, 1775) Homonym = argentosus Hayward, 1933 = argenteola (Matsumura, 1940) = ab. ‡"obliteratus" -

Alachua County's Rare and Endangered Species

ALACHUA COUNTY'S RARE AND ENDANGERED SPECIES MAMMALS SOURCE TAXON COMMON NAME FWS FWC FNAI'08 Eptesicus fuscus big brown bat S3 Myotis austroriparius Southeastern Bat S3 Neofiber alleni Florida round-tailed muskrat S3 Plecotus rafinesquii macrotus Southeastern big-eared bat S2 Podomys floridanus Florida mouse SSC S3 Sciurus niger shermani Sherman's fox squirrel SSC S3 Ursus americanus floridanus Florida black bear T S2 BIRDS SOURCE TAXON COMMON NAME FWS FWC FNAI'08 Accipiter cooperii Cooper’s hawk S3 Aimophila aestivalis Bachman’s sparrow S3 Aphelocoma coerulescens Florida scrub jay T T S2 Aramus guarauna limpkin SSC S3 Athene cunicularia floridana Florida burrowing owl SSC S3 Egretta caerulea little blue heron SSC Egretta thula snowy egret SSC S3 Egretta tricolor tricolored heron SSC Elanoides forficatus swallow-tailed kite S2 Eudocimus albus white ibis SSC Falco columbarius merlin S2 Falco peregrinus peregrine falcon E S2 Falco sparverius paulus Southeastern American kestrel T S3 Grus canadensis pratensis Florida sandhill crane T S2S3 Haliaeetus leucocephalus bald eagle S3 Helmitheros vermivorus worm-eating warbler S1 Laterallus jamaicensis black rail S2 Mycteria americana wood stork E E S2 Nyctanassa violacea yellow-crowned night heron S3 Nycticorax nycticorax black-crowned night heron S3 Picoides borealis red-cockaded woodpecker E SSC S2 Picoides villosus hairy woodpecker S3 Plegadis falcinellus glossy ibis S3 Seiurus motacilla Louisiana waterthrush S2 Setophaga ruticilla American redstart S2 Alachua County rare and endangered animal -

Species of Greatest Conservation Need

Appendix 1 - Species of Greatest Conservation Need Michigan’s Wildlife Action Plan 2015-2025 Cover Photos Credits Habitat – MNFI, Yu Man Lee Cerulean Warbler – Roger Eriksson MICHIGAN’S WILDLIFE ACTION PLAN 2015-2025 Species of Greatest Conservation Need List & Rationales SGCN List Mussels Snails A fingernail clam ( Pisidium simplex ) A land snail (no common name) ( Catinella gelida ) Black sandshell ( Ligumia recta ) A land snail (no common name) ( Catinella protracta ) Clubshell ( Pleurobema clava ) A land snail (no common name) ( Euconulus alderi ) Creek Heelsplitter ( Lasmigona compressa ) A land snail (no common name) ( Glyphyalinia solida ) Deertoe ( Truncilla truncata ) A land snail (no common name) ( Vallonia gracilicosta Eastern Elliptio ( Elliptio complanata ) albula ) Eastern pondmussel ( Ligumia nasuta ) A land snail (no common name) ( Vertigo modesta Elktoe ( Alasmidonta marginata ) modesta ) A land snail (no common name) ( Vertigo modesta Ellipse ( Venustaconcha ellipsiformis ) parietalis ) European pea clam ( Sphaerium corneum ) Acorn ramshorn ( Planorbella multivolvis ) Fawnsfoot ( Truncilla donaciformis ) An aquatic snail (no common name) ( Planorbella smithi ) Flutedshell ( Lasmigona costata ) Banded globe ( Anguispira kochi ) Giant northern pea clam ( Pisidium idahoense ) Boreal fossaria ( Fossaria galbana ) Greater European pea clam ( Pisidium amnicum ) Broadshoulder physa ( Physella parkeri ) Hickorynut ( Obovaria olivaria ) Brown walker ( Pomatiopsis cincinnatiensis ) Kidney shell ( Ptychobranchus fasciolaris ) Bugle -

Illustration Sources

APPENDIX ONE ILLUSTRATION SOURCES REF. CODE ABR Abrams, L. 1923–1960. Illustrated flora of the Pacific states. Stanford University Press, Stanford, CA. ADD Addisonia. 1916–1964. New York Botanical Garden, New York. Reprinted with permission from Addisonia, vol. 18, plate 579, Copyright © 1933, The New York Botanical Garden. ANDAnderson, E. and Woodson, R.E. 1935. The species of Tradescantia indigenous to the United States. Arnold Arboretum of Harvard University, Cambridge, MA. Reprinted with permission of the Arnold Arboretum of Harvard University. ANN Hollingworth A. 2005. Original illustrations. Published herein by the Botanical Research Institute of Texas, Fort Worth. Artist: Anne Hollingworth. ANO Anonymous. 1821. Medical botany. E. Cox and Sons, London. ARM Annual Rep. Missouri Bot. Gard. 1889–1912. Missouri Botanical Garden, St. Louis. BA1 Bailey, L.H. 1914–1917. The standard cyclopedia of horticulture. The Macmillan Company, New York. BA2 Bailey, L.H. and Bailey, E.Z. 1976. Hortus third: A concise dictionary of plants cultivated in the United States and Canada. Revised and expanded by the staff of the Liberty Hyde Bailey Hortorium. Cornell University. Macmillan Publishing Company, New York. Reprinted with permission from William Crepet and the L.H. Bailey Hortorium. Cornell University. BA3 Bailey, L.H. 1900–1902. Cyclopedia of American horticulture. Macmillan Publishing Company, New York. BB2 Britton, N.L. and Brown, A. 1913. An illustrated flora of the northern United States, Canada and the British posses- sions. Charles Scribner’s Sons, New York. BEA Beal, E.O. and Thieret, J.W. 1986. Aquatic and wetland plants of Kentucky. Kentucky Nature Preserves Commission, Frankfort. Reprinted with permission of Kentucky State Nature Preserves Commission.