Implications of Fish Stocking at Waldo Lake, Oregon by Jessica Bliss

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Central Cascades Wilderness Strategies Project Deschutes and Willamette National Forests Existing Conditions and Trends by Wilderness Area

May 31, 2017 Central Cascades Wilderness Strategies Project Deschutes and Willamette National Forests Existing Conditions and Trends by Wilderness Area Summary of Central Cascades Wilderness Areas ......................................................................................... 1 Mount Jefferson Wilderness ....................................................................................................................... 10 Mount Washington Wilderness .................................................................................................................. 22 Three Sisters Wilderness ............................................................................................................................. 28 Waldo Lake Wilderness ............................................................................................................................... 41 Diamond Peak Wilderness .......................................................................................................................... 43 Appendix A – Wilderness Solitude Monitoring ........................................................................................... 52 Appendix B – Standard Wilderness Regulations Concerning Visitor Use ................................................... 57 Summary of Central Cascades Wilderness Areas Introduction This document presents the current conditions for visitor management-related parameters in three themes: social, biophysical, and managerial settings. Conditions are described separately for each of -

A Bill to Designate Certain National Forest System Lands in the State of Oregon for Inclusion in the National Wilderness Preservation System and for Other Purposes

97 H.R.7340 Title: A bill to designate certain National Forest System lands in the State of Oregon for inclusion in the National Wilderness Preservation System and for other purposes. Sponsor: Rep Weaver, James H. [OR-4] (introduced 12/1/1982) Cosponsors (2) Latest Major Action: 12/15/1982 Failed of passage/not agreed to in House. Status: Failed to Receive 2/3's Vote to Suspend and Pass by Yea-Nay Vote: 247 - 141 (Record Vote No: 454). SUMMARY AS OF: 12/9/1982--Reported to House amended, Part I. (There is 1 other summary) (Reported to House from the Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs with amendment, H.Rept. 97-951 (Part I)) Oregon Wilderness Act of 1982 - Designates as components of the National Wilderness Preservation System the following lands in the State of Oregon: (1) the Columbia Gorge Wilderness in the Mount Hood National Forest; (2) the Salmon-Huckleberry Wilderness in the Mount Hood National Forest; (3) the Badger Creek Wilderness in the Mount Hood National Forest; (4) the Hidden Wilderness in the Mount Hood and Willamette National Forests; (5) the Middle Santiam Wilderness in the Willamette National Forest; (6) the Rock Creek Wilderness in the Siuslaw National Forest; (7) the Cummins Creek Wilderness in the Siuslaw National Forest; (8) the Boulder Creek Wilderness in the Umpqua National Forest; (9) the Rogue-Umpqua Divide Wilderness in the Umpqua and Rogue River National Forests; (10) the Grassy Knob Wilderness in and adjacent to the Siskiyou National Forest; (11) the Red Buttes Wilderness in and adjacent to the Siskiyou -

Lake Name Acres Depth Elevation National Forest/ BT CT RB BT-T RB

2017 SOUTH WILLAMETTE HIGH LAKES STOCKING Lake Name Species* GPS Coordinates Acres Depth Elevation National Forest/ NOTES BT CT RB BT-T RB-T Long Lat Wilderness** Abernathy, Lower NAT 43.6004313 -122.0982307 2 8' 4,950' Willamette NF - TH off FR5899 Abernathy, Upper NAT 43.6019144 -122.1011897 7 20' 4,960' Willamette NF - TH off FR5899 Aerial X X 43.98886915 -121.8738867 3 38' 5,400' Three Sisters Wilderness Mink Lake Basin Alameda X 43.4595055 -122.1573857 5 13' 5,500' Willamette NF Amstutz X 44.14173087 -121.8568697 2 20' 6,100' Three Sisters Wilderness Andrea X X 43.6198487 -122.2939419 6' 2,874' Willamette NF Andrews X 43.8548344 -122.3230379 2.4 18' 4,100' Benson X X 44.22161379 -121.9110135 20 55' 5,200' Mt. Washington Wilderness xc from Benson Lake trail #3502 Betty X 43.67673842 -122.0256862 40 28' 5,500' Waldo Lake Wilderness Birthday X 43.64364285 -122.0885188 3 11' 6,100' Waldo Lake Wilderness Blair NAT 43.8340519 -122.2393407 22.6 21' 4,750' Willamette NF Blue NAT 43.5306884 -121.2013972 13.2 33' 5,500' Diamond Peak Wilderness Boat NAT 43.9469003 -121.9262901 4 8' 5,100' Three Sisters Wilderness Bongo NAT 43.6914149 -122.0849723 6.9 14' 5,000' Waldo Lake Wilderness Boo Boo X X 43.62788785 -122.1093929 2.1 18' 5,400' Willamette NF Boot X X 43.93233415 -121.8850381 4.5 20' 5,270' Three Sisters Wilderness Mink Lake Basin Brittany X 43.77892474 -122.032864 4 29' 5,600' Waldo Lake Wilderness bushwhack from Rigdon Lake Bug X 43.3973286 -122.2248133 2.5 10' 5,000' Willamette NF Burnt Top X X 44.04265365 -121.8567562 20 28' 5,650' Three Sisters Wilderness via Horse Lake trail Cardiac X 43.7127412 -122.0921619 3.4 15' 5,500' Waldo Lake Wilderness xc from Koch Mtn trail #3576 Chetlo X X 43.75547637 -122.0743217 20 24' 5,289' Waldo Lake Wilderness Clare X X 44.27169097 -121.8998097 14 15' 4,500' Mt. -

High Elevation Surveys, Willamette NF

High Elevation Bryophyte Surveys Willamette National Forest Final Report March 2013 Project Objectives Our objective was to survey high priority, high elevation habitat for rocky outcrop and lakeside sensitive and strategic non vascular species on the Willamette National Forest during 2012. Few of these species are documented and most are suspected on the forest. Surveys in this habitat provide information on the range and rarity of these species. All surveys and special status species that were found in surveys (highlighted in red) have been entered into the NRIS TESP Database. Species codes from the USDA PLANTS database are used below for common tree species. Sweet Home District Surveys Surveys were conducted at upper Gordon Lake, Riggs Lake, Don Lake, Silver Lake, Crescent Lake, North Peak Lake, Heart Lake and Gordon Meadows. Cliffs adjacent to lakes were also surveyed. Surveys occurred in August and September, 2012. Surveyors were Ryan Murdoff, Alice Smith, Kate Richards and Anna Bonnette. Collections ranged from 0-10 bryophytes per site. Gordon Meadows 8/20/2012 T14S, R4E, Section 11 - UTM 0555208 4913002 Sphagnum sp., Potentilla palustris, Caltha biflora, Drosera rotundifolia, Hypericum anagalloides, Apargidium boreale, Kalmia occidentalis Collected 9 liverworts ; Alice Smith Upper Gordon Lake and meadow and cliff southwest of Upper Gordon Lake 9/17/2012 T14S, R5E, Section 18 - UTM 0558382 4911742 Gordon Lake: Sphagnum sp., Potentilla palustris, Menyanthes trifoliata, Carex lenticularis, Calamagrostis canadensis, Cicuta douglasii, -

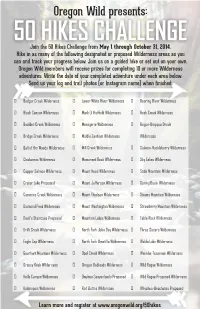

50 HIKES CHALLENGE Join the 50 Hikes Challenge from May 1 Through October 31, 2014

Oregon Wild presents: 50 HIKES CHALLENGE Join the 50 Hikes Challenge from May 1 through October 31, 2014. Hike in as many of the following designated or proposed Wilderness areas as you can and track your progress below. Join us on a guided hike or set out on your own. Oregon Wild members will receive prizes for completing 10 or more Wilderness adventures. Write the date of your completed adventure under each area below. Send us your log and trail photos (or Instagram name) when finished. � Badger Creek Wilderness � Lower White River Wilderness � Roaring River Wilderness � Black Canyon Wilderness � Mark O. Hatfield Wilderness � Rock Creek Wilderness � Boulder Creek Wilderness � Menagerie Wilderness � Rogue-Umpqua Divide � Bridge Creek Wilderness � Middle Santiam Wilderness Wilderness � Bull of the Woods Wilderness � Mill Creek Wilderness � Salmon-Huckleberry Wilderness � Clackamas Wilderness � Monument Rock Wilderness � Sky Lakes Wilderness � Copper Salmon Wilderness � Mount Hood Wilderness � Soda Mountain Wilderness � Crater Lake Proposed � Mount Jefferson Wilderness � Spring Basin Wilderness � Cummins Creek Wilderness � Mount Thielsen Wilderness � Steens Mountain Wilderness � Diamond Peak Wilderness � Mount Washington Wilderness � Strawberry Mountain Wilderness � Devil’s Staircase Proposed � Mountain Lakes Wilderness � Table Rock Wilderness � Drift Creek Wilderness � North Fork John Day Wilderness � Three Sisters Wilderness � Eagle Cap Wilderness � North Fork Umatilla Wilderness � Waldo Lake Wilderness � Gearhart Mountain Wilderness � Opal Creek Wilderness � Wenaha-Tucannon Wilderness � Grassy Knob Wilderness � Oregon Badlands Wilderness � Wild Rogue Wilderness � Hells Canyon Wilderness � Owyhee Canyonlands Proposed � Wild Rogue Proposed Wilderness � Kalmiopsis Wilderness � Red Buttes Wilderness � Whychus-Deschutes Proposed Learn more and register at www.oregonwild.org/50hikes. -

Pacific Northwest Wilderness

pacific northwest wilderness for the greatest good * Throughout this guide we use the term Wilderness with a capital W to signify lands that have been designated by Congress as part of the National Wilderness Preservation System whether we name them specifically or not, as opposed to land that has a wild quality but is not designated or managed as Wilderness. Table of Contents Outfitter/Guides Are Wilderness Partners .................................................3 The Promise of Wilderness ............................................................................4 Wilderness in our Backyard: Pacific Northwest Wilderness ...................7 Wilderness Provides .......................................................................................8 The Wilderness Experience — What’s Different? ......................................9 Wilderness Character ...................................................................................11 Keeping it Wild — Wilderness Management ...........................................13 Fish and Wildlife in Wilderness .................................................................15 Fire and Wilderness ......................................................................................17 Invasive Species and Wilderness ................................................................18 Climate Change and Wilderness ................................................................19 Resources ........................................................................................................21 -

Fiscal Year 2009

United States Department of Agriculture Monitoring and Forest Service Evaluation Report Pacific Northwest Region Willamette National Forest Fiscal Year 2009 Sahalie Fall, Willamette National Forest ii JULY 2010 Welcome to the 2008 Willamette National Forest annual Monitoring and Evaluation report. This is our 20th year implementing the 1990 Willamette National Forest Plan, and this report is intended to give you an update on the services and products we provide. Our professionals monitor a wide variety of forest resources and have summarized their findings for your review. I would like to introduce myself. I have been the Willamette National Forest Supervisor since last Fall and am so honored to be here. My focus will be to find new ways to accomplish our land management objectives, working even more closely with partners and universities so that we can most efficiently and effectively produce products and services. I believe that restoring and maintaining the health of our ecosystems depends on our ability to work together to share ideas, costs and solutions. I invite you to read this year’s report and contact myself or my staff with any questions, ideas, or concerns you may have. I appreciate your continued interest in the Willamette National Forest. Sincerely, ________________________________________ MEG MITCHELL Forest Supervisor Willamette National Forest r6-will-009-10 The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, age, disability, and where applicable, sex, marital status, familial status, parental status, religion, sexual orientation, genetic information, political beliefs, reprisal, or because all or part of an individual's income is derived from any public assistance program. -

Pacific Northwest Wilderness Pocket Guide

pacific northwest wilderness for the greatest good * Throughout this guide we use the term Wilderness with a capital W to signify lands that have been designated by Congress as part of the National Wilderness Preservation System whether we name them specifically or not, as opposed to land that has a wild quality but is not designated or managed as Wilderness. Table of Contents The Promise of Wilderness ............................................................................2 We Are All Wilderness Partners/Protectors...............................................4 Wilderness in our Backyard: Pacific Northwest Wilderness ...................7 Wilderness Provides .......................................................................................8 The Wilderness Experience — What’s Different? ......................................9 Wilderness Character ...................................................................................11 Keeping it Wild — Wilderness Management ...........................................13 Fish and Wildlife in Wilderness .................................................................15 Fire and Wilderness ......................................................................................17 Invasive Species and Wilderness ................................................................19 Climate Change and Wilderness ................................................................20 Resources ........................................................................................................22 -

December 28, 2018 Regional Forester, Objection

December 28, 2018 Regional Forester, Objection Reviewing Officer, Pacific Northwest Region, USDA Forest Service, Attn: 1570 Appeals and Objections, PO Box 3623, Portland, OR 97208-3623. Submitted Via Email: [email protected] Re: Central Cascades Wilderness Strategies Project-DRAFT DECISION Overview Access Fund, the American Alpine Club, the Mazamas, and Leavenworth Mountain Association are filing an objection regarding aspects of the Central Cascades Wilderness Strategies Project-DRAFT Decision Notice (DN) and request review and an objection resolution meeting. The Central Cascades Wilderness Strategies Project was initiated in 2017 with an overarching goal of reducing recreation-related impacts and preserving the Wilderness character of Mount Jefferson Wilderness, Mount Washington Wilderness, Three Sisters Wilderness, Waldo Lake Wilderness, and Diamond Peak Wilderness. The undersigned organizations submitted comments in May 2018 during the public comment period. There are several important traditional mountaineering opportunities in these Wilderness areas including iconic day-use climbing objectives, like Jefferson Park Glacier, the North Ridge of Mt. Washington, and South Sister. We recognize the importance of managing visitor impacts to protect Wilderness character and natural resources, however we do not support aspects of the selected Alternative 4 Modified in the DN. The DN proposes a seasonal limited entry permit system be implemented within the Mt. Jefferson, Mt. Washington, and Three Sisters Wilderness areas at 30 trailheads for day use and at all trailheads for overnight use. Objections Previous comments submitted by Access Fund, the American Alpine Club, the Mazamas, and Leavenworth Mountain Association during the Central Cascades Wilderness Strategies Project-DRAFT environmental assessment (EA) public comment period included, but were not limited to, the following objections: 1) Wilderness Policy a. -

Monitoring and Evaluation Report

United States Department of Agriculture Monitoring and Forest Service Evaluation Report Pacific Northwest Region Willamette National Forest Fiscal Year 2010 Fish Lake, Willamette National Forest ii JULY 2011 Welcome to the 2010 Willamette National Forest annual Monitoring and Evaluation report. This is our 20th year implementing the 1990 Willamette National Forest Plan, and this report is intended to give you an update on the services and products we provide. Our professionals monitor a wide variety of forest resources and have summarized their findings for your review. The climate in which we began implementing the Forest Land and Resource Management Plan (LRMP) in 1991, has changed considerably. The largest change occurred in 1994 when the Northwest Forest Plan amended our LRMP by establishing new land allocations. Climate change is now a subject of concern. We want to know what changes, if any, will occur on this forest We have added a monitoring question to address this subject. I invite you to read this year’s report and contact myself or my staff with any questions, ideas, or concerns you may have. I appreciate your continued interest in the Willamette National Forest. Sincerely, MEG MITCHELL Forest Supervisor Willamette National Forest r6-will-009-11 The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, age, disability, and where applicable, sex, marital status, familial status, parental status, religion, sexual orientation, genetic information, political beliefs, reprisal, or because all or part of an individual's income is derived from any public assistance program. -

10 Most Endangered Places 2013 an Oregon Wild Report

Oregon’s 10 Most Endangered Places 2013 an Oregon Wild Report 1 Oregon WIld 2010 10 Most Endangered Places Our mission: Since 1974, Oregon Wild has worked to protect and restore Oregon’s wildlands, wildlife, and waters as an enduring legacy for future generations. Editor: Submissions by: Marielle Cowdin American Rivers, Inc. Hells Canyon Preservation Council Contributors: Klamath-Siskiyou Wildlands Center Darilyn Brown Klamiopsis Audubon Society Forrest English Friends of Kalmiopsis Erik Fernandez Friends of the Columbia Gorge Chris Hansen The Larch Company Doug Heiken Northwest Rafting Company Chandra LeGue Oregon Natural Desert Association Steve Pedery Rogue Riverkeeper Laura Stevens Sierra Club Barbara Ullian Soda Mountain Wilderness Council Veronica Warnock Umpqua Watersheds WaterWatch To find out more about our Western Environmental Law Center conservation work please visit www.oregonwild.org *Fold out the cover for a spectacular Western Oregon Backyard COVER: TIM GIRAUDIER 2 OregonForest WIld 2010 (Devil’s Staircase Proposed Wilderness) poster ABOVE: NEIL SCHULMAN BRIZZ MEDDINGS HUGH HOCHMAN KEN MORRISH Oregon: A State of Outdoors & A Tale of Two Economies Let’s get down to business. Oregon’s future, our future, landscape are the lifeblood of local communities, as well depends on the long-term investments we make in our as our most powerful magnet for tourism. From lush state. We stand now with two paths before us, each with coastal forests and towering Doug firs, to grasslands, radically different economic and environmental canyons, and vanilla-scented ponderosa stands, few states consequences. To choose which path we walk we must rival Oregon’s ecoregional diversity and status as an ask ourselves: What do we value as Oregonians and what is outdoor adventure mecca. -

2018 Route Guide

2018 ROUTE GUIDE The Oregon Timber Trail is an iconic 670-mile backcountry mountain bike route spanning Oregon’s diverse landscapes from California to the Columbia River Gorge. © Dylan VanWeelden TABLE OF CONTENTS The small towns the route passes through, large amount of alpine singletrack and people of Oregon and Cascadia were truly special! - 2017 OTT Rider Overview . 6 By the numbers . 12 Logistics . 18 Getting There . 19 Stay Connected . 19 Is this route for you? . 19 Season & Climate . 20 Navigation and wayfi nding . 21 Resupply & water . 22 Camping and Lodging . 23 Leave No Trace . 24 Other trail users . 26 A note about trails . 27 4 © Gabriel Amadeus Disclaimer . 27 Springwater School Contribution . 27 Gateway Communities . 28 Fremont Tier . 34 Segment 1 of 10 - Basin Range . 40 Segment 2 of 10 - Winter Rim . 42 Segment 3 of 10 - Mazama Blowout . 46 Willamette Tier . 48 Segment 4 of 10 - Kalapuya Country . 52 Segment 5 of 10 - Bunchgrass Ridge . 56 Deschutes Tier . 60 Segment 6 of 10 - Cascade Peaks . 64 Segment 7 of 10 - Santiam Wagon Road . 67 Hood Tier . 70 Segment 8 of 10 - Old Cascade Crest. 75 Segment 9 of 10 - Wy’East. 78 Segment 10 of 10 - The Gorge. 80 Oregon Timber Trail Alliance . 84 5 Kim and Sam, Oregon Timber Trail Pioneers. © Leslie Kehmeier The Oregon Timber Trail is an iconic 670-mile backcountry mountain bike route spanning Oregon’s diverse landscapes from California to the Columbia River Gorge. The Oregon Timber Trail is a world-class bikepacking destination and North America’s premiere long- distance mountain bike route.