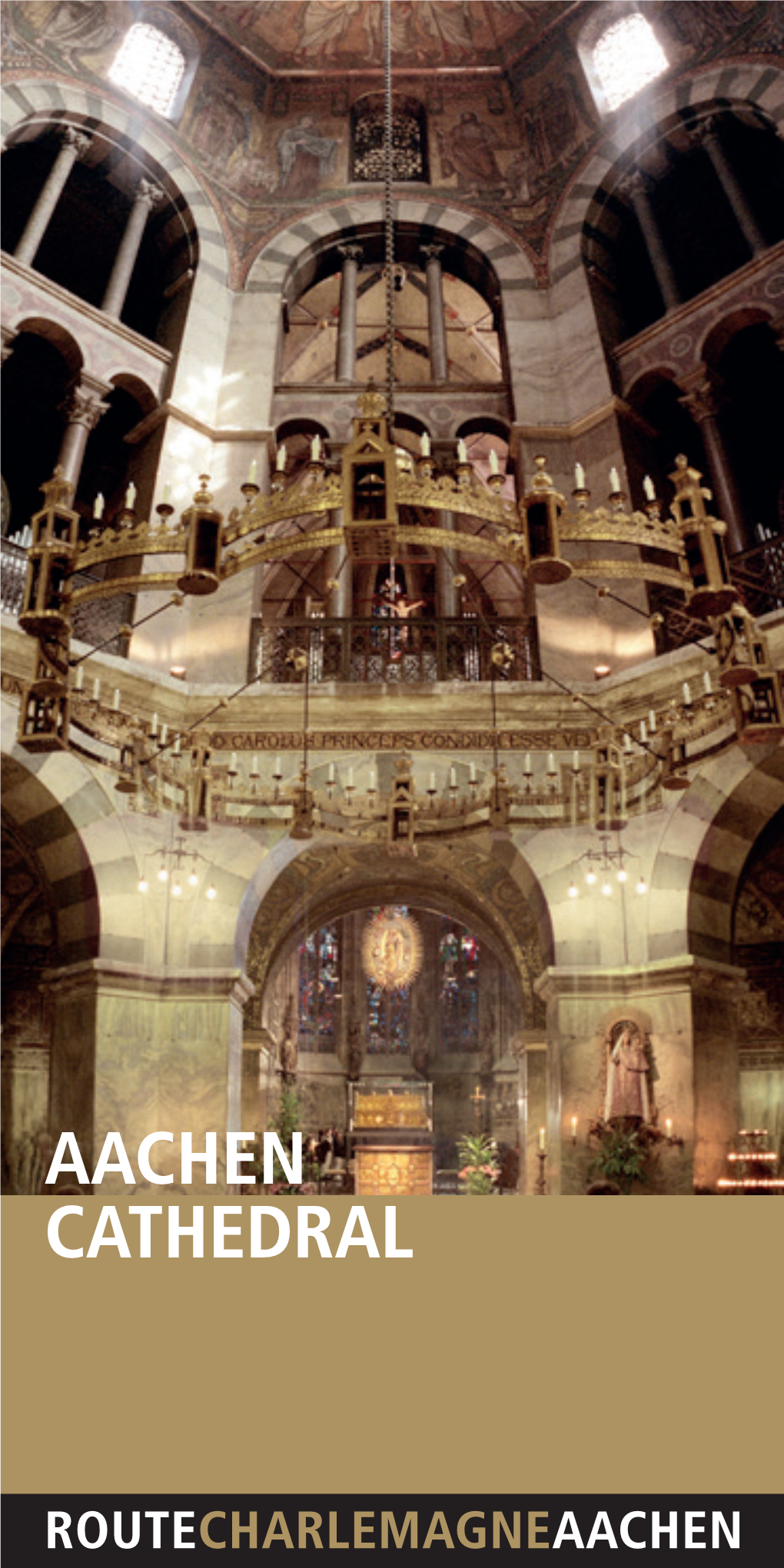

Aachen Cathedral

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE TOWN HALL Station on the Route Charlemagne Table of Contents

THE TOWN HALL Station on the Route Charlemagne Table of contents Route Charlemagne 3 Palace of Charlemagne 4 History of the Building 6 Gothic Town Hall 6 Baroque period 7 Neo-Gothic restoration 8 Destruction and rebuilding 9 Tour 10 Foyer 10 Council Hall 11 White Hall 12 Master Craftsmen‘s Court 13 Master Craftsmen‘s Kitchen 14 “Peace Hall“ (Red Hall) 15 Ark Staircase 16 Charlemagne Prize 17 Coronation Hall 18 Service 22 Information 23 Imprint 23 7 6 5 1 2 3 4 Plan of the ground floor 2 The Town Hall Route Charlemagne Aachen‘s Route Charlemagne connects significant locations around the city to create a path through history – one that leads from the past into the future. At the centre of the Route Charlemagne is the former palace complex of Charlemagne, with the Katschhof, the Town Hall and the Cathedral still bearing witness today of a site that formed the focal point of the first empire of truly European proportions. Aachen is a historical town, a centre of science and learning, and a European city whose story can be seen as a history of Europe. This story, along with other major themes like religion, power, economy and media, are all reflected and explored in places like the Cathedral and the Town Hall, the International Newspaper Museum, the Grashaus, Haus Löwenstein, the Couven-Museum, the Axis of Science, the SuperC of the RWTH Aachen University and the Elisenbrunnen. The central starting point of the Route Charlemagne is the Centre Charlemagne, the new city museum located on the Katschhof between the Town Hall and the Cathedral. -

The Anglo-Saxon Transformations of the Biblical Themes in the Old English Poem the Dream of the Rood

Zeszyty Naukowe Towarzystwa Doktorantów UJ Nauki Humanistyczne, Nr 8 (1/2014) ALEKSANDRA MRÓWKA (JAGIELLONIAN UNIVERSITY) THE ANGLO-SAXON TRANSFORMATIONS OF THE BIBLICAL THEMES IN THE OLD ENGLISH POEM THE DREAM OF THE ROOD ABSTRACT The main aim of this article is to present the Old English poem The Dream of the Rood as a literary work successfully mingling Christian and Germanic tradi- tions. The poet very skillfully applies the pattern of traditional secular heroic poetry to Christian subject-matter creating a coherent unity. The Biblical themes and motifs are shaped by the Germanic frame of mind because the addressees of the poem were a warrior society with a developed ethos of honour and cour- age, quite likely to identify with a god who professed the same values. Although the Christian story of the Passion is narrated from the Anglo-Saxon point of view, the most fundamental values coming from the suffering of Jesus and his key role in God’s plan to redeem mankind remain unchanged: the universal notions of Redemption, Salvation and Heavenly Kingdom do not lose their pri- mary meaning. KEY WORDS Bible, rood, crucifixion, Anglo-Saxon, transformation ABOUT THE AUTHOR Aleksandra Mrówka The Department of the History of British Literature and Culture Jagiellonian University in Kraków e-mail: [email protected] 125 Aleksandra Mrówka __________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ The Dream of the Rood is a masterpiece of Old English religious poetry. Written in alliterative verse and maintained in the convention of dream allegory, this piece of early medieval literature is a mixture of Christian and Anglo-Saxon traditions. Although they seem to be contrasting, they are not antagonistic: these two worlds mingle together creating a coherent unity. -

History and Culture

HISTORY AND CULTURE A HAMBURG PORTUGUESE IN THE SERVICE OF THE HAGANAH: THE TRIAL AGAINST DAVID SEALTIEL IN HAMBURG (1937) Ina Lorenz (Hamburg. Germany) Spotlighted in the story here to be told is David de Benjamin Sealtiel (Shaltiel, 1903–1969), a Sephardi Jew from Hamburg, who from 1934 worked for the Haganah in Palestine as a weapons buyer. He paid for that activity with 862 days in incarceration under extremely difficult conditions of detention in the concentration camps of the SS.1 Jewish Immigration into Palestine and the Founding of the Haganah2 In order to be able to effectively protect the new Jewish settlements in Palestine from Arab attacks, and since possession of weapons was prohibited under the British Mandatory administration, arms and munitions initially were generally being smuggled into Palestine via French- controlled Syria. The leaders of the Haganah and Histadrut transformed the Haganah with the help of the Jewish Agency from a more or less untrained militia into a paramilitary group. The organization, led by Yisrael Galili (1911–1986), which in the rapidly growing Jewish towns had approximately 10,000 members, continued to be subordinate to the civilian leadership of the Histadrut. The Histadrut also was responsible for the ———— 1 Michael Studemund-Halévy has dealt with the fascinating, complex personality of David Sealtiel/Shaltiel in a number of publications in German, Hebrew, French and English: “From Hamburg to Paris”; “Vom Shaliach in den Yishuv”; “Sioniste au par- fum romanesque”; “David Shaltiel.” See also [Shaltiel, David]. “In meines Vaters Haus”; Scholem. “Erinnerungen an David Shaltiel (1903–1968).” The short bio- graphical sketches on David Sealtiel are often based on inadequate, incorrect, wrong or fictitious informations: Avidar-Tschernovitz. -

Communal Commercial Check City of Aachen

Eigentum von Fahrländer Partner AG, Zürich Communal commercial check City of Aachen Location Commune Aachen (Code: 5334002) Location Aachen (PLZ: 52062) (FPRE: DE-05-000334) Commune type City District Städteregion Aachen District type District Federal state North Rhine-Westphalia Topics 1 Labour market 9 Accessibility and infrastructure 2 Key figures: Economy 10 Perspectives 2030 3 Branch structure and structural change 4 Key branches 5 Branch division comparison 6 Population 7 Taxes, income and purchasing power 8 Market rents and price levels Fahrländer Partner AG Communal commercial check: City of Aachen 3rd quarter 2021 Raumentwicklung Eigentum von Fahrländer Partner AG, Zürich Summary Macro location text commerce City of Aachen Aachen (PLZ: 52062) lies in the City of Aachen in the District Städteregion Aachen in the federal state of North Rhine-Westphalia. Aachen has a population of 248'960 inhabitants (31.12.2019), living in 142'724 households. Thus, the average number of persons per household is 1.74. The yearly average net migration between 2014 and 2019 for Städteregion Aachen is 1'364 persons. In comparison to national numbers, average migration tendencies can be observed in Aachen within this time span. According to Fahrländer Partner (FPRE), in 2018 approximately 34.3% of the resident households on municipality level belong to the upper social class (Germany: 31.5%), 33.6% of the households belong to the middle class (Germany: 35.3%) and 32.0% to the lower social class (Germany: 33.2%). The yearly purchasing power per inhabitant in 2020 and on the communal level amounts to 22'591 EUR, at the federal state level North Rhine-Westphalia to 23'445 EUR and on national level to 23'766 EUR. -

The Carolingian Past in Post-Carolingian Europe Simon Maclean

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by St Andrews Research Repository 1 The Carolingian Past in Post-Carolingian Europe Simon MacLean On 28 January 893, a 13-year-old known to posterity as Charles III “the Simple” (or “Straightforward”) was crowned king of West Francia at the great cathedral of Rheims. Charles was a great-great-grandson in the direct male line of the emperor Charlemagne andclung tightly to his Carolingian heritage throughout his life.1 Indeed, 28 January was chosen for the coronation precisely because it was the anniversary of his great ancestor’s death in 814. However, the coronation, for all its pointed symbolism, was not a simple continuation of his family’s long-standing hegemony – it was an act of rebellion. Five years earlier, in 888, a dearth of viable successors to the emperor Charles the Fat had shattered the monopoly on royal authority which the Carolingian dynasty had claimed since 751. The succession crisis resolved itself via the appearance in all of the Frankish kingdoms of kings from outside the family’s male line (and in some cases from outside the family altogether) including, in West Francia, the erstwhile count of Paris Odo – and while Charles’s family would again hold royal status for a substantial part of the tenth century, in the long run it was Odo’s, the Capetians, which prevailed. Charles the Simple, then, was a man displaced in time: a Carolingian marooned in a post-Carolingian political world where belonging to the dynasty of Charlemagne had lost its hegemonic significance , however loudly it was proclaimed.2 His dilemma represents a peculiar syndrome of the tenth century and stands as a symbol for the theme of this article, which asks how members of the tenth-century ruling class perceived their relationship to the Carolingian past. -

Church Building Terms What Do Narthex and Nave Mean? Our Church Building Terms Explained a Virtual Class Prepared by Charles E.DICKSON,Ph.D

Welcome to OUR 4th VIRTUAL GSP class. Church Building Terms What Do Narthex and Nave Mean? Our Church Building Terms Explained A Virtual Class Prepared by Charles E.DICKSON,Ph.D. Lord Jesus Christ, may our church be a temple of your presence and a house of prayer. Be always near us when we seek you in this place. Draw us to you, when we come alone and when we come with others, to find comfort and wisdom, to be supported and strengthened, to rejoice and give thanks. May it be here, Lord Christ, that we are made one with you and with one another, so that our lives are sustained and sanctified for your service. Amen. HISTORY OF CHURCH BUILDINGS The Bible's authors never thought of the church as a building. To early Christians the word “church” referred to the act of assembling together rather than to the building itself. As long as the Roman government did not did not recognize and protect Christian places of worship, Christians of the first centuries met in Jewish places of worship, in privately owned houses, at grave sites of saints and loved ones, and even outdoors. In Rome, there are indications that early Christians met in other public spaces such as warehouses or apartment buildings. The domus ecclesiae or house church was a large private house--not just the home of an extended family, its slaves, and employees--but also the household’s place of business. Such a house could accommodate congregations of about 100-150 people. 3rd-century house church in Dura-Europos, in what is now Syria CHURCH BUILDINGS In the second half of the 3rd century, Christians began to construct their first halls for worship (aula ecclesiae). -

Interreg I / Ii : Cross-Border Cooperation

INTERREG I / II : CROSS-BORDER COOPERATION Euregio Meuse-Rhine: implementation and management in practice Speech by Mr K.H. Lambertz - Chair of the Monitoring Committee for the Euregio Meuse-Rhine Interreg Programme - Director of Euregio Meuse-Rhine - Minister-President of the German-speaking community of Belgium 1. General background and geographical situation In 1974, the governors of the Dutch and Belgian provinces of Limburg, together with the Chief Executive of the Cologne county administration, acted on the proposal made to them by the future Queen of the Netherlands, Princess Beatrix, during an official visit to Maastricht, to draw up draft arrangements for an association under which even closer cross-border collaboration could develop, along the lines of the Dutch-German Euregio project that had been running since 1957. This initiative was part of the new Community direction in regional policy, which in 1975 was to be provided with an instrument to assist economic development called the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF). In 1976, the principle of cross-border institutions was passed in law. Initially formed as an ad hoc association, the Euregio Meuse-Rhine was designed to promote integration between inhabitants on each side of the national borders. The area covers: • in Holland: the southern part of the Dutch province of Limburg; • in Germany: the city of Aachen, and the districts of Aachen, Heinsberg, Düren and Euskirchen, which make up the Aachen Regio, and • in Belgium: the entire province of Limburg. The province of Liège joined the Euregio Meuse-Rhine in 1978. In 1992, the German-speaking community of Belgium became the fifth partner in the Euregio Meuse- Rhine. -

The Capital Sculpture of Wells Cathedral: Masons, Patrons and The

The Capital Sculpture of Wells Cathedral: Masons, Patrons and the Margins of English Gothic Architecture MATTHEW M. REEVE For Eric Fernie This paper considers the sculpted capitals in Wells cathedral. Although integral to the early Gothic fabric, they have hitherto eluded close examination as either a component of the building or as an important cycle of ecclesiastical imagery in their own right. Consideration of the archaeological evidence suggests that the capitals were introduced mid-way through the building campaigns and were likely the products of the cathedral’s masons rather than part of an original scheme for the cathedral as a whole. Possible sources for the images are considered. The distribution of the capitals in lay and clerical spaces of the cathedral leads to discussion of how the imagery might have been meaningful to diCerent audiences on either side of the choir screen. introduction THE capital sculpture of Wells Cathedral has the dubious honour of being one of the most frequently published but least studied image cycles in English medieval art. The capitals of the nave, transepts, and north porch of the early Gothic church are ornamented with a rich array of figural sculptures ranging from hybrid human-animals, dragons, and Old Testament prophets, to representations of the trades that inhabit stiC-leaf foliage, which were originally highlighted with paint (Figs 1, 2).1 The capitals sit upon a highly sophisticated pier design formed by a central cruciform support with triple shafts at each termination and in the angles, which oCered the possibility for a range of continuous and individual sculpted designs in the capitals above (Fig. -

The Instrumental Cross and the Use of the Gospel Book Troyes, Bibliothèque Municipale MS 960

The Instrumental Cross and the Use of the Gospel Book Troyes, Bibliothèque Municipale MS 960 Beatrice Kitzinger In approximately 909, a Breton named Matian together with his wife Digrenet donated a gospel manuscript to a church called Rosbeith. They intended it should remain there on pain of anathema, never to be taken from the church by force but provided with a dispensation for removal by students for the express purpose of writing or reading. With the exception of the date, which is recorded elsewhere in the manuscript, these specifications all appear in a short text written in distinctive, highlighted script at the close of Luke’s chapter list (f. 71): These little letters recount how Matian, and his wife Digrenet, gave these four books of the gospel as a gift to the church of Rosbeith for their souls. And whosoever should remove this evangelium from that church by force, may he be anathema—excepting a student [in order] to write or to read.1 The location of Rosbeith is unknown, but we may surmise that it was a church attached to a larger abbey in Brittany, according to Breton nomenclature.2 Apart from their Breton origins and evident appreciation for scholarship, the identities of Matian and Digrenet are similarly murky. The particularizing nature of the note extends only to a statement of Matian and Digrenet’s motive for the gift—“for their souls”—and a designation of the contents: “these four books of the gospel.” We know, however, that the couple was anxious Kitzinger – Instrumental Cross about the fate of their souls at judgment, and we know that they thought the gospel manuscript at hand might help. -

BYZANTINE CAMEOS and the AESTHETICS of the ICON By

BYZANTINE CAMEOS AND THE AESTHETICS OF THE ICON by James A. Magruder, III A dissertation submitted to Johns Hopkins University in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Baltimore, Maryland March 2014 © 2014 James A. Magruder, III All rights reserved Abstract Byzantine icons have attracted artists and art historians to what they saw as the flat style of large painted panels. They tend to understand this flatness as a repudiation of the Classical priority to represent Nature and an affirmation of otherworldly spirituality. However, many extant sacred portraits from the Byzantine period were executed in relief in precious materials, such as gemstones, ivory or gold. Byzantine writers describe contemporary icons as lifelike, sometimes even coming to life with divine power. The question is what Byzantine Christians hoped to represent by crafting small icons in precious materials, specifically cameos. The dissertation catalogs and analyzes Byzantine cameos from the end of Iconoclasm (843) until the fall of Constantinople (1453). They have not received comprehensive treatment before, but since they represent saints in iconic poses, they provide a good corpus of icons comparable to icons in other media. Their durability and the difficulty of reworking them also makes them a particularly faithful record of Byzantine priorities regarding the icon as a genre. In addition, the dissertation surveys theological texts that comment on or illustrate stone to understand what role the materiality of Byzantine cameos played in choosing stone relief for icons. Finally, it examines Byzantine epigrams written about or for icons to define the terms that shaped icon production. -

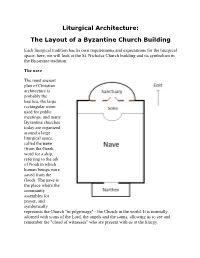

Liturgical Architecture: the Layout of a Byzantine Church Building

Liturgical Architecture: The Layout of a Byzantine Church Building Each liturgical tradition has its own requirements and expectations for the liturgical space; here, we will look at the St. Nicholas Church building and its symbolism in the Byzantine tradition. The nave The most ancient plan of Christian architecture is probably the basilica, the large rectangular room used for public meetings, and many Byzantine churches today are organized around a large liturgical space, called the nave (from the Greek word for a ship, referring to the ark of Noah in which human beings were saved from the flood). The nave is the place where the community assembles for prayer, and symbolically represents the Church "in pilgrimage" - the Church in the world. It is normally adorned with icons of the Lord, the angels and the saints, allowing us to see and remember the "cloud of witnesses" who are present with us at the liturgy. At St. Nicholas, the nave opens upward to a dome with stained glass of the Eucharist chalice and the Holy Spirit above the congregation. The nave is also provided with lights that at specific times the church interior can be brightly lit, especially at moments of great joy in the services, or dimly lit, like during parts of the Liturgy of Presanctified Gifts. The nave, where the congregation resides during the Divine Liturgy, at St. Nicholas is round, representing the endlessness of eternity. The principal church building of the Byzantine Rite, the Church of Holy Wisdom (Hagia Sophia) in Constantinople, employed a round plan for the nave, and this has been imitated in many Byzantine church buildings. -

NORTH RHINE WESTPHALIA 10 REASONS YOU SHOULD VISIT in 2019 the Mini Guide

NORTH RHINE WESTPHALIA 10 REASONS YOU SHOULD VISIT IN 2019 The mini guide In association with Commercial Editor Olivia Lee Editor-in-Chief Lyn Hughes Art Director Graham Berridge Writer Marcel Krueger Managing Editor Tom Hawker Managing Director Tilly McAuliffe Publishing Director John Innes ([email protected]) Publisher Catriona Bolger ([email protected]) Commercial Manager Adam Lloyds ([email protected]) Copyright Wanderlust Publications Ltd 2019 Cover KölnKongress GmbH 2 www.nrw-tourism.com/highlights2019 NORTH RHINE-WESTPHALIA Welcome On hearing the name North Rhine- Westphalia, your first thought might be North Rhine Where and What? This colourful region of western Germany, bordering the Netherlands and Belgium, is perhaps better known by its iconic cities; Cologne, Düsseldorf, Bonn. But North Rhine-Westphalia has far more to offer than a smattering of famous names, including over 900 museums, thousands of kilometres of cycleways and a calendar of exciting events lined up for the coming year. ONLINE Over the next few pages INFO we offer just a handful of the Head to many reasons you should visit nrw-tourism.com in 2019. And with direct flights for more information across the UK taking less than 90 minutes, it’s the perfect destination to slip away to on a Friday and still be back in time for your Monday commute. Published by Olivia Lee Editor www.nrw-tourism.com/highlights2019 3 NORTH RHINE-WESTPHALIA DID YOU KNOW? Despite being landlocked, North Rhine-Westphalia has over 1,500km of rivers, 360km of canals and more than 200 lakes. ‘Father Rhine’ weaves 226km through the state, from Bad Honnef in the south to Kleve in the north.