WP 1 Comparative Report 3

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Minutes of the 2020 SBI Telco Meeting Recommendations For

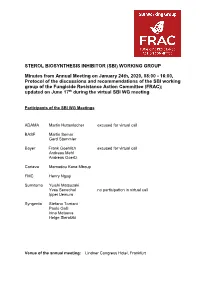

STEROL BIOSYNTHESIS INHIBITOR (SBI) WORKING GROUP Minutes from Annual Meeting on January 24th, 2020, 08:00 - 16:00, Protocol of the discussions and recommendations of the SBI working group of the Fungicide Resistance Action Committee (FRAC); updated on June 17th during the virtual SBI WG meeting Participants of the SBI WG Meetings ADAMA Martin Huttenlocher excused for virtual call BASF Martin Semar Gerd Stammler Bayer Frank Goehlich excused for virtual call Andreas Mehl Andreas Goertz Corteva Mamadou Kane Mboup FMC Henry Ngugi Sumitomo Yuichi Matsuzaki Yves Senechal no participation in virtual call Ippei Uemura Syngenta Stefano Torriani Paolo Galli Irina Metaeva Helge Sierotzki Venue of the annual meeting: Lindner Congress Hotel, Frankfurt Hosting organization: FRAC/Crop Life International Disclaimer The technical information contained in the global guidelines/the website/the publication/the minutes is provided to CropLife International/RAC members, non- members, the scientific community and a broader public audience. While CropLife International and the RACs make every effort to present accurate and reliable information in the guidelines, CropLife International and the RACs do not guarantee the accuracy, completeness, efficacy, timeliness, or correct sequencing of such information. CropLife International and the RACs assume no responsibility for consequences resulting from the use of their information, or in any respect for the content of such information, including but not limited to errors or omissions, the accuracy or reasonableness of factual or scientific assumptions, studies or conclusions. Inclusion of active ingredients and products on the RAC Code Lists is based on scientific evaluation of their modes of action; it does not provide any kind of testimonial for the use of a product or a judgment on efficacy. -

Outgoing Chancellor Sebastian Kurz's People's Party (ÖVP) Favourite in the Snap Election in Austria on 29Th September Next

GENERAL ELECTION IN AUSTRIA 29th September 2019 European Outgoing Chancellor Sebastian Elections Monitor Kurz’s People’s Party (ÖVP) favourite in the snap election in Corinne Deloy Austria on 29th September next Analysis 6.4 million Austrians aged at least 16 are being called leadership of the FPÖ. He was replaced by Norbert Hofer, to ballot on 29th September to elect the 183 members Transport Minister and the unlucky candidate in the last of the National Council (Nationalrat), the lower house presidential election in 2016, when he won 48.3% of the of Parliament. This election, which is being held three vote and was beaten by Alexander Van der Bellen (51.7%) years ahead of schedule, follows the dismissal of the in the second round of the election on 4th December. government chaired by Chancellor Kurz (People’s Party, ÖVP) by the National Council on 27th May last. It was the The day after the European elections, Chancellor first time in the country’s history that a government lost Sebastian Kurz was removed from office. On 3rd June, a vote of confidence (103 of the 183 MPs voted against). Brigitte Bierlein, president of the Constitutional Court, It is even more remarkable that on the day before the became the first female Chancellor in Austria’s history. vote regarding his dismissal, the ÖVP easily won the Appointed by the President of the Republic Van der Bellen, European elections on 26th May with 34.55% of the vote. she has ensured the interim as head of government. On 21st June the Austrian authorities announced that a snap This vote of no-confidence followed the broadcast, ten election would take place on 29th September. -

ENGLISH Original: GERMAN

CIO.GAL/3/17 12 January 2017 ENGLISH Original: GERMAN STATEMENT BY THE OSCE CHAIRPERSON-IN-OFFICE AND FEDERAL MINISTER FOR EUROPE, INTEGRATION AND FOREIGN AFFAIRS OF THE REPUBLIC OF AUSTRIA, HIS EXCELLENCY SEBASTIAN KURZ, AT THE 1127th (SPECIAL) MEETING OF THE OSCE PERMANENT COUNCIL 12 January 2016 Mr. Secretary General, Dear colleagues, I am pleased to be here with you today for the first time as Chairperson-in-Office of our Organization. The success of our work together has an immediate and direct impact on the security of all of us. Austria, as an active participating State and the host country of the OSCE, has always attached the utmost importance to the Organization. Austria traditionally sees its role as a bridge-builder and a place of dialogue. We seek transparency as an honest broker. More than ever in times of great challenges, in which our continent is reverting to the bloc-based thinking of the past, this is important to us. We therefore agreed to assume the Chairmanship for the second time following our Chairmanship in 2000 in order to make a contribution to restoring stability and security. I should like first of all to congratulate and thank the outgoing German Chairmanship for its efforts over the past year. The results of the Ministerial Council in Hamburg give direction to the work of our, and future, OSCE Chairmanships. In recent years, we have witnessed a resurgence of mistrust and instability. In the OSCE area, in addition to the crisis in and around Ukraine, which is a root cause of this loss of trust, there are also other conflicts that we thought belonged to the past. -

General Elections in Austria 15Th October 2017

General elections in Austria 15th October 2017 Results of the general elections on 15th October 2017 in Austria Turnout: 79,5% 2 Political Parties No of votes won % of votes cast No of seats Austrian People’s Party (ÖVP) 1 587 826 31,5 62 Social Democratic Party (SPÖ) 1 353 481 26,9 52 Liberal Party (FPÖ) 1 311 358 26 51 NEOS – New Austria 265 217 5,3 10 Peter Pilz List 220 656 4,4 8 The Greens-Alternative Green(DG) 190 092 3,8 0 Others 136 314 2,10 0 Source: Home Affairs Ministry https://wahl17.bmi.gv.at “Voters have given us important responsibilities. We everything now points towards the return of the FPÖ have to be aware of this and we must also be aware of to office eleven years after being thrown out. An the hope that we represent. There is much to be done. alliance between the ÖVP and the FPÖ indeed seems We have to introduce a new style of politics in Austria. to be the most likely hypothesis. Sebastian Kurz I want to try with all my might to bring change to the has never hidden the fact that he has sympathies country,” declared Sebastian Kurz when the results with the populists, notably regarding the migratory were announced. “We shall form a coalition for the next question, and declared during his campaign that he five years with the party that will enable us to provide was prepared to join forces with the FPÖ to win a the country with the greatest change,” indicated the majority in Parliament. -

Xenophobia, Radicalism, and Hate Crime in Europe

Institute for the Study of National Policy and Interethnic Relations European International Tolerance Centre Centre for Monitoring and Comparative Analysis of Intercultural Communications (Moscow Institute of Psychoanalysis) European Centre for Democracy Development Xenophobia, Radicalism, and Hate Crime in Europe Annual Report Amsterdam-Athens-Budapest-Berlin-Bratislava-Warsaw-Dublin-Zagreb-London- Madrid-Kiev-Moscow-Paris-Rome 2018 1 Editor in Chief and Project Head: Dr. Valery Engel, President of the European Centre for Democracy Development, Director of the Institute for the Study of National Policy and Interethnic Relations, Head of the Centre for Monitoring and Comparative Analysis of Intercultural Communications (Moscow Institute of Psychoanalysis) Authors: Dr. Valery Engel (general analysis); Dr. Jean-Yves Camus (France); Dr. Matthew Feldman (UK); Dr. William Allchorn (UK); Dr. Anna Castriota (Italy); Dr. Ildikó Barna (Hungary); Bulcsú Hunyadi (Hungary); Dr.Patrik Szicherle (Hungary); Dr. Farah Rasmi (Hungary; Dr. Vanja Ljujic (Netherlands); Dr. Marcus Rheindorf (Austria); Pranvera Tika (Greece); Katarzyna du Val (Poland);; Dr. Dmitry Stratievsky (Germany); Ruslan Bortnik (Ukraine); Dr. Anna Luboevich (Croatia); Dr. Ilya Tarasov (Slovakia); Dr. Anna García Juanatei (Spain); Dr. Bettina Schteible (Spain); Maxim Semenov (Ukraine) Translation: Marina Peunova (USA), Proofread and edited by Natasha Neary (Northumbria University, UK) The authors thank the Chairman of the European Centre for Tolerance, Mr. Vladimir Shternfeld, as well as Dr. Lev Surat, Head of the Moscow Institute of Psychoanalysis and Dr. Igor Surat, Head of the Moscow Economical Institute, for their support of the project Xenophobia, Radicalism, and Hate Crime in Europe, 2018. Moscow: Editus, 2018. – XX pp. This book is another annual report on major manifestations of hate in the European space in 2017-2018. -

Justice in European Political Discourse – Comparative Report of Six Country Cases

Justice in European Political Discourse – comparative report of six country cases Dorota Lepianka This Report was written within the framework of Work Package 4 “Political, advocacy and media discourse of justice and fairness’’ June 18 Funded by the Horizon 2020 Framework Programme of the European Union Acknowledgements This report would not have been possible without the contribution of researchers who have prepared country reports (listed in the Bibliography section): Wanda Tiefenbacher (ETC-Graz, Austria), Eva Zemandl (CEU, Hungary), Maria Paula Meneses, Bruno Sena Martins and Laura Brito (CES, Portugal), Ayse Buğra and Mehmet Ertan Want to learn more about what we are working (Bogazici Universitesi, Turkey), Claudia Hartman, Pier-Luc on? Dupont and Bridget Anderson (University of Bristol, the United Kingdom) and Basak Akkan (Bogazici Universitesi, Visit us at: Turkey) – a co-author of the report on the European : https://ethos-europe.eu normative framework of justice. Their contribution, Website patience in answering questions and advice have been Facebook: www.facebook.com/ethosjustice/ invaluable. All mistakes and possible misinterpretations are mine alone. Blog: www.ethosjustice.wordpress.com Twitter: www.twitter.com/ethosjustice Hashtag: #ETHOSjustice Youtube: www.youtube.com/ethosjustice European Landscapes of Justice (web) app: http://myjustice.eu/ This publication has been produced with the financial support of the Horizon 2020 Framework Programme of the European Union. The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of the authors and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of the European Commission. Copyright © 2018, ETHOS consortium – All rights reserved ETHOS project The ETHOS project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No. -

Annual Report 2017 Important Dates in 2018

Annual report 2017 Important dates in 2018 Annual General Meeting Uponor Corporation’s Annual General Meeting will be held on Tuesday, 13 March 2018 at 15:00 EET at the Helsinki Exhibition and Convention Centre, Messuaukio 1, Helsinki, Finland. Financial accounts bulletin for 2017 15 February 08:00 EET Financial statements for 2017 15 February - Annual General Meeting 13 March 15:00 EET Record date for dividend payment 1st instalment: 15 March* - 2nd instalment: 6 September* Date for dividend payment 1st instalment: 22 March* - 2nd instalment: 13 September* Interim report: January–March 3 May 14:00 EET Interim report: January–June 25 July 08:00 EET Interim report: January–September 24 October 08:00 EET * Proposal of the Board of Directors Investor Relations at Uponor Enquiries Shareholder enquiries Contact Group [email protected] [email protected] Communications Uponor Corporation, Meeting requests Reetta Härkki, General Counsel Group Communications Päivi Dahlqvist, Executive Tel. +358 (0)20 129 2835 P.O. Box 37, Äyritie 20 Assistant [email protected] FI-01511 Vantaa, Finland Tel. +358 (0)20 129 2823 Tel. +358 (0)20 129 2854 [email protected] Change of address [email protected] Shareholders are requested to Other IR contacts notify their custodian bank, their Follow us Maija Strandberg, CFO brokerage firm, or any other On social media: Tel. +358 (0)20 129 2830 financial institution responsible [email protected] for maintaining their book-entry securities account of any changes Tarmo Anttila, Vice President, -

Minutes of the 2017 SBI Meeting Recommendations for 2018

STEROL BIOSYNTHESIS INHIBITOR (SBI) WORKING GROUP Annual Meeting 2017 on December 15, 2017, 08:00 –16:15 Protocol of the discussions and recommendations of the SBI working group of the Fungicide Resistance Action Committee (FRAC) Participants of the SBI WG Meeting on December 15, 2017 ADAMA Martin Huttenlocher (excused) BASF Martin Semar Gerd Stammler Bayer Frank Goehlich Andreas Mehl Klaus Stenzel Dow/DuPont Greg Kemmitt Sumitomo Norio Kimura (excused) Yves Senechal Ippei Uemura Syngenta Steve Dale Stefano Torriani Birgit Forster (excused) FRAC Brazil chairman Rogerio Augusto Bortolan, Bayer; chairman (excused) (for soybean only) Venue of the meeting: Lindner Congress Hotel, Frankfurt Hosting organization: FRAC/Crop Life International Anti-Trust Guidelines (from FRAC Constitution) were shown before the Meeting started FRAC SBI 2017 WG protocol 1 www.frac.info 1. DMI AND AMINES: CEREAL DISEASES 1. 1. WHEAT 1.1.1. Leaf spot (Mycosphaerella graminicola / Septoria tritici) Presentation of monitoring data BASF, Bayer, Syngenta Disease pressure was moderate in most of the European countries but regionally variable in 2017. DMIs field performance was good when used according to the manufacturers and FRAC recommendations. No general field resistance has been reported. Monitoring was carried out in Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Croatia, Czech Republic, Denmark, France, Germany, Greece, Italy, Ireland, Latvia, Lithuania, Netherlands, Poland, Romania, Russia, Slovakia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Ukraine, and United Kingdom. After the slight increase in the frequency of less sensitive isolates from 2002 to 2004, the situation had stabilised between 2005 and 2008. In 2009 a trend to slightly higher EC50 values was observed in important cereal growing areas (France, Germany, Ireland, United Kingdom), this trend has slowed down in 2010 to 2012 and was stable in 2013. -

Xenophobia, Radicalism, and Hate Crime in Europe (2018)

Institute for the Study of National Policy and Interethnic Relations European International Tolerance Centre Centre for Monitoring and Comparative Analysis of Intercultural Communications (Moscow Institute of Psychoanalysis) European Centre for Democracy Development Xenophobia, Radicalism, and Hate Crime in Europe Annual Report Amsterdam-Athens-Budapest-Berlin-Bratislava-Warsaw-Dublin-Zagreb-London- Madrid-Kiev-Moscow-Paris-Rome -Viena 2018 1 Editor in Chief and Project Head: Dr. Valery Engel, President of the European Centre for Democracy Development, Director of the Institute for the Study of National Policy and Interethnic Relations, Head of the Centre for Monitoring and Comparative Analysis of Intercultural Communications (Moscow Institute of Psychoanalysis) Authors: Dr. Valery Engel (general analysis); Dr. Jean-Yves Camus (France); Dr. Matthew Feldman (UK); Dr. William Allchorn (UK); Dr. Anna Castriota (Italy); Dr. Ildikó Barna (Hungary); Bulcsú Hunyadi (Hungary); Dr.Patrik Szicherle (Hungary); Dr. Farah Rasmi (Hungary; Dr. Vanja Ljujic (Netherlands); Dr. Marcus Rheindorf (Austria); Pranvera Tika (Greece); Katarzyna du Val (Poland);; Dr. Dmitry Stratievsky (Germany); Ruslan Bortnik (Ukraine); Dr. Anna Luboevich (Croatia); Dr. Ilya Tarasov (Slovakia); Dr. Ana García Juanatey (Spain); Dr. Bettina Steible (Spain); Maxim Semenov (Ukraine) Translation: Marina Peunova (USA), Proofread and edited by Natasha Neary (Northumbria University, UK) The authors thank the Chairman of the European Centre for Tolerance, Mr. Vladimir Shternfeld, as well as Dr. Lev Surat, Head of the Moscow Institute of Psychoanalysis and Dr. Igor Surat, Head of the Moscow Economical Institute, for their support of the project Xenophobia, Radicalism, and Hate Crime in Europe, 2018. Moscow: Editus, 2018. – XX pp. This book is another annual report on major manifestations of hate in the European space in 2017-2018. -

Integration of Refugees in Austria, Germany and Sweden: Comparative Analysis

DIRECTORATE GENERAL FOR INTERNAL POLICIES POLICY DEPARTMENT A: ECONOMIC AND SCIENTIFIC POLICY Integration of Refugees in Austria, Germany and Sweden: Comparative Analysis STUDY Abstract This note presents a comparative analysis of policies and practices to facilitate the labour market integration of beneficiaries of international protection in the main destination countries of asylum seekers in 2015/2016, namely Austria, Germany and Sweden. It focuses on the development of policy strategies to adapt the asylum and integration system to the high numbers of new arrivals. Special attention is given to the political discourse and public opinion on asylum and integration of refugees. Innovative approaches with respect to labour market integration are highlighted as well as gaps. Finally, the study includes lessons learned from recent policy developments as well as policy recommendations in order to improve labour market integration of asylum seekers and refugees. The study has been produced at request of the Employment and Social Affairs Committee. IP/A/EMPL/2016-23 January 2018 PE 614.200 EN This document was requested by the European Parliament's Committee on Employment and Social Affairs. AUTHOR Regina KONLE-SEIDL, Institute for Employment Research (IAB) RESPONSIBLE ADMINISTRATOR Susanne KRAATZ EDITORIAL ASSISTANT Laurent HAMERS LINGUISTIC VERSIONS Original: EN ABOUT THE EDITOR Policy departments provide in-house and external expertise to support EP committees and other parliamentary bodies in shaping legislation and exercising democratic