Integration of Refugees in Austria, Germany and Sweden: Comparative Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Dairy Milk Sector in Lower Saxony and Germany

The Dairy Milk Sector in Lower Saxony and Germany Compiled by Max Lesemann, IHK Hannover October 2020 Inhalt List of figures and tables ................................................................................. Index of abbreviations .................................................................................... I. Introduction .......................................................................................... 5 II. Market ................................................................................................. 6 I. Company Structures and Federations ..................................................... 6 II. Production ...................................................................................... 8 III. International Trade ......................................................................... 12 IV. Consumption ................................................................................. 15 III. Digitalization, Industry 4.0 and Internet of Things in the milk industry .......... 20 IV. Sustainability ................................................................................... 22 V. Innovations and Trends ...................................................................... 29 VI. Prospect ......................................................................................... 31 VII. Bibliography ..................................................................................... 34 List of figures and tables Figure 1: The amount of different milk products per year from 2014 to 2018 -

Report for Austria– Questionnaire Related the Administration Control

ADMINISTRATIVE JUSTICE IN EUROPE – Report for Austria– Questionnaire related the administration control list and typology in the 25 Member States of the European Union Preliminary. 1. Administration jurisdictional control was one typical concern of the liberal streams in the 19th century. In Austria, “the Reichsgericht”, a precursor of the Constitutional Court, was created by the December 1867 constitution which also planned creation of a Supreme Administrative Court (hereafter “the Verwaltungsgerichtshof”). However, this project was only fulfilled in 1876. Following this, the Verwaltungsgerichtshof played a decisive role in developing the legal protection system in Austria, establishing fundamental principles for administrative procedural law. Between 1934 and 1938, the Constitutional Court and the Verwaltungsgerichtshof merged to become “the Bundesgerichtshof”. Several judges were retired for political reasons. The introductions of Chambers with extended composition and of actions for administrative failure to act were significant reforms. After 1938, “the Bundesgerichtshof” lost its authority as Constitutional Court as well as several of its administrative jurisdiction authorities. Several judges were retired for political reasons. In 1940 “the Bundesgerichtshof” became “the Verwaltungsgerichtshof in Vienna” which was an administrative authority of the Reich. In 1941, the Verwaltungsgerichtshof became the “Vienna Außensenat” of the “Reichsverwaltungsgericht” by forming an organisational association with other German administrative courts. A few weeks after the Austrian declaration of independence in 1945, Chancellor Renner commissioned Mr. Coreth to revive the Verwaltungsgerichtshof which took up its duties again on 7th December 1945. The legal text on the Verwaltungsgerichtshof was amended and reissued several times but, in substance, it is still in force today. In 1945, the Constitutional Court was re-established with the same capacities as 1933 and it began carrying out its duties again in 1946. -

Older People in Germany and the EU 2016

OLDER PEOPLE in Germany and the EU Federal Statistical Office of Germany Published by Photo credits Federal Statistical Office, Wiesbaden Cover image Title © Monkey Business Images / Editing Shutterstock.com Thomas Haustein, Johanna Mischke, Frederike Schönfeld, Ilka Willand Page 9 © iStockphoto.com / vitranc Page 53 © iStockphoto.com / XiXinXing Page 16 © Image Source / Topaz / F1online Page 60 © Peter Atkins - Fotolia.com English version edited by Michaela Raimer, Page 17 © iStockphoto.com / Squaredpixels Page 67 © iStockphoto.com / Kristina Theis Page 27 © Westend61 - Fotolia.com monkeybusinessimages Page 29 © bluedesign - Fotolia.com Page 71 © iStockphoto.com / PeopleImages Design and layout Page 31 © iStockphoto.com / Xavier Arnau Page 73 © runzelkorn - Fotolia.com Federal Statistical Office Page 36 © iStockphoto.com / mheim3011 Page 75 © iStockphoto.com / Published in October 2016 Page 37 © iStockphoto.com / miriam-doerr Christopher Badzioch Page 39 © Lise_Noergel / photocase.de Page 77 © iStockphoto.com / funstock Order number: 0010021-16900-1 Page 40 © iStockphoto.com / budgaugh Page 80 © iconimage - Fotolia.com Page 45 © Statistisches Bundesamt Page 89 © iStockphoto.com / vm Page 46 © iStockphoto.com / Attila Barabas Page 90 © frau.L. / photocase.de Page 49 © iStockphoto.com / Gizelka Page 93 © fusho1d - Fotolia.com Page 49 © iStockphoto.com / Vladyslav Danilin Page 51 © iStockphoto.com / pamspix This brochure was published with the financial support of the Federal Ministry for Family Affairs, Senior Citizens, Women and Youth. -

Daimler Annual Report 2014

Annual Report 2014. Key Figures. Daimler Group 2014 2013 2012 14/13 Amounts in millions of euros % change Revenue 129,872 117,982 114,297 +10 1 Western Europe 43,722 41,123 39,377 +6 thereof Germany 20,449 20,227 19,722 +1 NAFTA 38,025 32,925 31,914 +15 thereof United States 33,310 28,597 27,233 +16 Asia 29,446 24,481 25,126 +20 thereof China 13,294 10,705 10,782 +24 Other markets 18,679 19,453 17,880 -4 Investment in property, plant and equipment 4,844 4,975 4,827 -3 Research and development expenditure 2 5,680 5,489 5,644 +3 thereof capitalized 1,148 1,284 1,465 -11 Free cash flow of the industrial business 5,479 4,842 1,452 +13 EBIT 3 10,752 10,815 8,820 -1 Value added 3 4,416 5,921 4,300 -25 Net profit 3 7,290 8,720 6,830 -16 Earnings per share (in €) 3 6.51 6.40 6.02 +2 Total dividend 2,621 2,407 2,349 +9 Dividend per share (in €) 2.45 2.25 2.20 +9 Employees (December 31) 279,972 274,616 275,087 +2 1 Adjusted for the effects of currency translation, revenue increased by 12%. 2 For the year 2013, the figures have been adjusted due to reclassifications within functional costs. 3 For the year 2012, the figures have been adjusted, primarily for effects arising from application of the amended version of IAS 19. Cover photo: Mercedes-Benz Future Truck 2025. -

Austria: Vienna

Guide to Catholic-Related Records outside the U.S. about Native Americans See User Guide for help on interpreting entries Archdiocese of Vienna new 2004 AUSTRIA, VIENNA Archdiocese of Vienna Archives AT- 2 A-1010 Wollzeile 2 Wien, Oesterreich Phone 43 1 51552 http://stephanscom.at/ Hours: Monday, Tuesday, and Thursday, 8:30-1:00, 2:00-4:00; and Friday, 8:30-12:00 Access: Some restrictions apply Copying facilities: Yes History of the Leopoldine Society 1827 Bishop Edward D. Fenwick, O.P. of Cincinnati, Ohio sent Reverend John Fréderic Résé to Europe to recruit German- speaking priests and financial assistance for the Cincinnati Diocese; Reverend Samuel Mazzuchelli, O.P. (1806-1864) was among those recruited 1829 In response, the Leopoldine Society (Leopoldinen Stetiftung) was established in Vienna with headquarters at the Augustinian monastery; it solicited German- speaking priests and financial assistance from the dioceses of the Austrian Empire for needy dioceses in the United States, some of which had American Indian missions 1830-1910 The Leopoldine Society donated about $680,500 (3,402,000 kronen) to U.S. dioceses; those with Indian missions that received notable funding included Boise, Cincinnati, Detroit, Grand Rapids, Green Bay, Lead (later renamed Rapid City), Marquette, Nesqually (later renamed Seattle), Oregon (later renamed Portland in Oregon), and Tucson Before 1850 Due to efforts by the Leopoldine Society, several priests from the Austrian Empire emigrated to the United States; those who became missionaries to American Indians include Reverend Frederic I. Baraga (first bishop of the Diocese of Marquette, Michigan), Reverend Joseph F. Buh, Reverend Ignatius Mrak (second bishop of the Diocese of Marquette, Michigan), Reverend Francis Pierz, and Reverend Otto Skolla, O.F.M. -

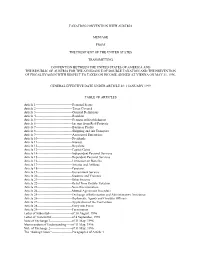

Taxation Convention with Austria Message from The

TAXATION CONVENTION WITH AUSTRIA MESSAGE FROM THE PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES TRANSMITTING CONVENTION BETWEEN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA AND THE REPUBLIC OF AUSTRIA FOR THE AVOIDANCE OF DOUBLE TAXATION AND THE PREVENTION OF FISCAL EVASION WITH RESPECT TO TAXES ON INCOME, SIGNED AT VIENNA ON MAY 31, 1996. GENERAL EFFECTIVE DATE UNDER ARTICLE 28: 1 JANUARY 1999 TABLE OF ARTICLES Article 1----------------------------------Personal Scope Article 2----------------------------------Taxes Covered Article 3----------------------------------General Definitions Article 4----------------------------------Resident Article 5----------------------------------Permanent Establishment Article 6----------------------------------Income from Real Property Article 7----------------------------------Business Profits Article 8----------------------------------Shipping and Air Transport Article 9----------------------------------Associated Enterprises Article 10--------------------------------Dividends Article 11--------------------------------Interest Article 12--------------------------------Royalties Article 13--------------------------------Capital Gains Article 14--------------------------------Independent Personal Services Article 15--------------------------------Dependent Personal Services Article 16--------------------------------Limitation on Benefits Article 17--------------------------------Artistes and Athletes Article 18--------------------------------Pensions Article 19--------------------------------Government Service Article 20--------------------------------Students -

Low Fertility in Austria and the Czech Republic: Gradual Policy Adjustments

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Sobotka, Tomáš Working Paper Low fertility in Austria and the Czech Republic: Gradual policy adjustments Vienna Institute of Demography Working Papers, No. 2/2015 Provided in Cooperation with: Vienna Institute of Demography (VID), Austrian Academy of Sciences Suggested Citation: Sobotka, Tomáš (2015) : Low fertility in Austria and the Czech Republic: Gradual policy adjustments, Vienna Institute of Demography Working Papers, No. 2/2015, Austrian Academy of Sciences (ÖAW), Vienna Institute of Demography (VID), Vienna This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/110987 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten -

Global Austria Austria’S Place in Europe and the World

Global Austria Austria’s Place in Europe and the World Günter Bischof, Fritz Plasser (Eds.) Anton Pelinka, Alexander Smith, Guest Editors CONTEMPORARY AUSTRIAN STUDIES | Volume 20 innsbruck university press Copyright ©2011 by University of New Orleans Press, New Orleans, Louisiana, USA. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. All inquiries should be addressed to UNO Press, University of New Orleans, ED 210, 2000 Lakeshore Drive, New Orleans, LA, 70119, USA. www.unopress.org. Book design: Lindsay Maples Cover cartoon by Ironimus (1992) provided by the archives of Die Presse in Vienna and permission to publish granted by Gustav Peichl. Published in North America by Published in Europe by University of New Orleans Press Innsbruck University Press ISBN 978-1-60801-062-2 ISBN 978-3-9028112-0-2 Contemporary Austrian Studies Sponsored by the University of New Orleans and Universität Innsbruck Editors Günter Bischof, CenterAustria, University of New Orleans Fritz Plasser, Universität Innsbruck Production Editor Copy Editor Bill Lavender Lindsay Maples University of New Orleans University of New Orleans Executive Editors Klaus Frantz, Universität Innsbruck Susan Krantz, University of New Orleans Advisory Board Siegfried Beer Helmut Konrad Universität Graz Universität -

Boznia and Herzegovina

Grids & Datums BOZNIA AND HERZEGOVINA by Clifford J. Mugnier, C.P., C.M.S. “The region’s ancient inhabitants were Illyrians, followed by the Ro- Austria-Hungarians pushed Bosnia and Herzegovina into the modern mans who settled around the mineral springs at Ilidža near Sarajevo in age with industrialization, the development of coal mining and the 9AD. When the Roman Empire was divided in 395AD, the Drina River, building of railways and infrastructure. Ivo Andric´ ’s Bridge over the today the border with Serbia, became the line dividing the Western Drina succinctly describes these changes in the town of Višegrad. But Roman Empire from Byzantium. The Slavs arrived in the late 6th and political unrest was on the rise. Previously, Bosnian Muslims, Catholics early 7th centuries. In 960 the region became independent of Serbia, and Orthodox Christians had only differentiated themselves from each only to pass through the hands of other conquerors: Croatia (PE&RS, other in terms of religion. But with the rise of nationalism in the mid- July 2012), Byzantium, Duklja (modern-day Montenegro) and Hungary 19th century, Bosnia’s Catholic and Orthodox population started to (PE&RS, April 1999). Bosnia’s medieval history is a much-debated identify themselves with neighboring Croatia or Serbia respectively. subject, mainly because different groups have tried to claim authen- At the same time, resentment against foreign occupation intensified ticity and territorial rights on the basis of their interpretation of the and young people across the sectarian divide started cooperating with country’s religious make-up before the arrival of the Turks. -

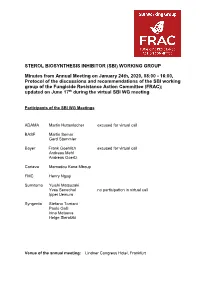

Minutes of the 2020 SBI Telco Meeting Recommendations For

STEROL BIOSYNTHESIS INHIBITOR (SBI) WORKING GROUP Minutes from Annual Meeting on January 24th, 2020, 08:00 - 16:00, Protocol of the discussions and recommendations of the SBI working group of the Fungicide Resistance Action Committee (FRAC); updated on June 17th during the virtual SBI WG meeting Participants of the SBI WG Meetings ADAMA Martin Huttenlocher excused for virtual call BASF Martin Semar Gerd Stammler Bayer Frank Goehlich excused for virtual call Andreas Mehl Andreas Goertz Corteva Mamadou Kane Mboup FMC Henry Ngugi Sumitomo Yuichi Matsuzaki Yves Senechal no participation in virtual call Ippei Uemura Syngenta Stefano Torriani Paolo Galli Irina Metaeva Helge Sierotzki Venue of the annual meeting: Lindner Congress Hotel, Frankfurt Hosting organization: FRAC/Crop Life International Disclaimer The technical information contained in the global guidelines/the website/the publication/the minutes is provided to CropLife International/RAC members, non- members, the scientific community and a broader public audience. While CropLife International and the RACs make every effort to present accurate and reliable information in the guidelines, CropLife International and the RACs do not guarantee the accuracy, completeness, efficacy, timeliness, or correct sequencing of such information. CropLife International and the RACs assume no responsibility for consequences resulting from the use of their information, or in any respect for the content of such information, including but not limited to errors or omissions, the accuracy or reasonableness of factual or scientific assumptions, studies or conclusions. Inclusion of active ingredients and products on the RAC Code Lists is based on scientific evaluation of their modes of action; it does not provide any kind of testimonial for the use of a product or a judgment on efficacy. -

Report 26: Barriers to Climate Change Adaptation in Urban Areas In

Barriers to Climate Change Adaptation in Urban Areas in Germany REPORT 26 Titelbild: © istock/Ridofranz Zitierhinweis: P. Weyrich (2016): Barriers to Climate Change Adaptation in Urban Areas in Germany. Report 26. Climate Service Center Germany, Hamburg. Erscheinungsdatum: August 2016 Dieser Report ist auch online unter www.climate-service-center.de erhältlich. Report 26 Barriers to Climate Change Adaptation in Urban Areas in Germany Master’s Thesis M.Sc. Global Change Ecology University of Bayreuth Supervisors: Dr. Joachim Rathmann, PD Dr. Steffen Bender Mentor: Dr. Jörg Cortekar Author: Philippe Weyrich Department „Climate Impacts and Economics“ at Climate Service Center Germany (GERICS) August 2016 Table of content List of figures .......................................................................................................................... 4 List of tables ........................................................................................................................... 5 List of abbreviations .............................................................................................................. 6 1. Introduction .................................................................................................................... 7 2. Climate change in urban areas in Germany ................................................................. 9 2.1. Observed changes worldwide and in Germany ........................................................ 9 2.2. Projected changes worldwide and in Germany ..................................................... -

COVID-19 Associated Discrimination in Germany: Realistic and Symbolic Threats1,2

COVID-19 associated discrimination in Germany: Realistic and symbolic threats1,2 Jörg Dollmann*a,b and Irena Kogana aMannheim Centre for European Social Research MZES, Mannheim University bGerman Centre for Integration and Migration Research (DeZIM), Berlin *corresponding author: [email protected] August 2020 Abstract The contribution focusses on Covid-19 associated discrimination (CAD) in Germany and asks whether immigrants from Asian origin are increasingly discriminated against during the COVID-19 pandemic and whether other immigrant groups face similar threats. Using data from the COVID-19 add-on-survey for CILS4EU-DE (CILS4COVID), we demonstrate that immigrants from Asian origin report an increasing CAD during the pandemic, which is more pronounced for respondents residing in administrative districts with a more dynamic COVID-19 situation. Similar results can be found for respondents originating from both American continents and from countries of the former Soviet Union. Given that COVID-19 was first reported in Asia, but with rather low number of infections later on, and the rather high infection rates on both American continents and in Russia, we conclude that CAD experienced by these groups might happen in a reaction to both realistic and symbolic threats posed by the virus. Motivation The novel coronavirus COVID-19 has not only brought the most severe challenge to the global economy, stability and social order since the World War II, the instances of ethnic and racial discrimination have considerably increased in many countries (Ng 2020; He et al. 2020; Pew Research Center 2020). Discrimination toward people who share social or 1 A revised version of this manuscript has been published in Research in Social Stratification and Mobility and is available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rssm.2021.100631.