Justice in European Political Discourse – Comparative Report of Six Country Cases

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Green Chances in the New Hungarian Parliament by Róbert László The

Green Chances in the New Hungarian Parliament by Róbert László The next Hungarian parliament could include two green formations, one of which, Dialogue for Hungary (PM), will surely have some members in parliament, although very much open to question is whether it will have its own parliamentary group. At the moment, it is doubtful whether the other formation, Politics Can Be Different (LMP), will surpass the election threshold, but if it does an independent parliamentary group is guaranteed. The Hungarian Socialist Party (MSZP), Together 2014 (Együtt 2014), Dialogue for Hungary, the Democratic Coalition (DK) and the Hungarian Liberal Party (MLP) will contest the forthcoming parliamentary elections – scheduled for 6 April 2014 – with a joint list and common candidates. Apart from the far-right party Jobbik, only the green party Politics Can Be Different will contest the elections independently from the ruling parties and the left-of-centre Alliance. Many smaller formations running for election stand basically no chance of overcoming the 5% parliamentary threshold. The new electoral system benefits the relative winner even more than before, which is one of the key reasons why the divided left was forced to form an alliance. The other one is that support for Together 2014, the formation led by former Prime Minister Gordon Bajnai and reinforced by the representatives of PM who left LMP a year ago, was dangerously nearing the election threshold of 5%, while the formerly mere 1-2% support for DK rose to almost the same heights. This dynamic undermined the previous electoral agreement between the Socialists and Together 2014-PM, which envisaged the parties presenting their own candidate lists. -

Left-Wing Movements' Boom in Hungary

Left-wing movements’ boom in Hungary - Analysis of the situation of the Hungarian opposition - Tamás Boros – Arbeitspapier – Friedrich Ebert Stiftung Budapest Oktober 2012 Left-wing movements’ boom in Hungary - Analysis of the situation of the Hungarian opposition - Tamás Boros The Hungarian left-wing and liberal opposition faces an unprecedented situation: with the weakening of the Hungarian Socialist Party (MSZP) and the disappearance of its traditional coalition partner, the liberal Alliance of Free Democrats (SZDSZ) in 2010, new parties and movements have started to rise in an effort to become inevitable politi- cal actors at the time of the next elections in 2014. The crucial question of the next two years is whether the Hungarian Socialist Party will be able to win the elections by itself, and, if not, whether an alliance of opposition movements can be created which will be able to defeat the current prime minister, Viktor Orbán. Between 1998 and 2010 a quasi two-party system characterised Hungary, where the Hungari- an Socialist Party and its liberal coalition partner faced off with the conservative Fidesz. The decision of the voters was as simple as choosing between the two sides – other parties, wheth- er brand new ones or ones with traditional ties, did not stand a reasonable chance of becoming a major political force in Hungary. By 2010, however, eight years spent in government had eroded the popularity of left-wing parties to such an extent that MSZP lost 60% of its former voters (1.4 million people) and SZDSZ all but disappeared from the political map of Hungary. -

With the Final Votes Counted, Fidesz Has Secured a ‘Super

With the final votes counted, Fidesz has secured a ‘super- provided by LSE Research Online View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk CORE majbrought to youo by rity’ in Hungary, but it is questionable how fair the election really was blogs.lse.ac.uk/europpblog/2014/04/16/with-the-final-votes-counted-fidesz-has-secured-a-super-majority-in- hungary-but-it-is-questionable-how-fair-the-election-really-was/ 16/04/2014 Hungary held elections on 6 April, with the ruling Fidesz party winning a clear majority of seats. While there was initially some doubt over whether Fidesz had secured the ‘super-majority’ in parliament needed to amend the country’s constitution, the final results announced on 12 April indicated that it had met this target. Agnes Batory writes that although the parliamentary opposition carries some of the blame for its defeat, the electoral reforms passed in the previous parliament by Fidesz also had an impact on the result, with some observers concluding that the elections were ultimately ‘free but not fair’. On 6 April Hungarians went to the polls for the sixth time since regime change in 1990. They returned to power PM Viktor Orbán’s Fidesz, an erstwhile liberal youth movement turned national-conservative or, as many say, populist. Since 2010, Orbán’s party has held a two-thirds majority in Parliament, allowing it to change laws of constitutional standing – a political tool used to its full potential against the Fidesz’s main opponents in the left-liberal camp. Of the 2.7 million voters supporting the party’s list four years ago, over 625,000, or about 23 per cent deserted the party. -

The Hungarian National Assembly

Directorate-General for the Presidency Directorate for Relations with National Parliaments Factsheet: The Hungarian National Assembly 1. At a glance Hungary is a republic and a parliamentary democracy. The Hungarian National Assembly (Magyar Országgyűlés) is a unicameral body. The 199 Members of the National Assembly are directly elected by the citizens. Elections to the National Assembly must take place every four years at the latest, and are based on the principles of proportional representation. In May 2014, in the last elections, 106 Members were elected in individual voting districts, 93 Members were elected from national-level lists, which could be put forward by a political party or a national minority. The voting age for national Parliamentary elections is 18 years. The Assembly includes 16 standing committees, which debate and report on bills and supervise the work of ministers. One committee is dedicated to the spokespersons of the 13 minorities (nationality advocates) present in Hungary. The current Hungarian government under Prime Minister Mr Viktor Orbán (FIDESZ/EPP) is composed of the FIDESZ/EPP - KDNP/EPP coalition. The current President of Hungary is Mr János Áder, a former MEP of FIDESZ/EPP. 2. Composition Results of the parliamentary elections on 6 April 2014 Party EP affiliation % Seats FIDESZ- Magyar Polgári Szövetség (FIDESZ) FIDESZ - Hungarian Civic Union 59,1% 117 Magyar Szocialista Párt (MSZP) - Hungarian Socialist Party - EGYÜTT - PM - Together - Dialogue for Hungary - 14,1% 28 Demokratikus Koalíció (DK) - Democratic Coalition - Magyar Liberális Párt (MLP) Hungarian Liberal Party Jobbik Magyarországért Mozgalom (JOBBIK) Non- Movement for a Better Hungary attached 11,6% 23 Kereszténydemokrata Néppárt (KDNP) Christian Democratic People's Party 8,1% 16 Lehet Más a Politika (LMP) Politics Can Be Different 2,5% 5 Others Non- 4,5% 9 attached 100% 199 Turnout: 61,2% The next National Assembly elections must take place in spring 2018 at the latest. -

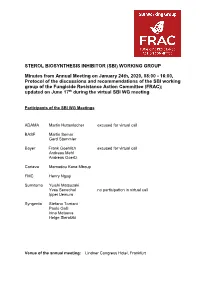

Minutes of the 2020 SBI Telco Meeting Recommendations For

STEROL BIOSYNTHESIS INHIBITOR (SBI) WORKING GROUP Minutes from Annual Meeting on January 24th, 2020, 08:00 - 16:00, Protocol of the discussions and recommendations of the SBI working group of the Fungicide Resistance Action Committee (FRAC); updated on June 17th during the virtual SBI WG meeting Participants of the SBI WG Meetings ADAMA Martin Huttenlocher excused for virtual call BASF Martin Semar Gerd Stammler Bayer Frank Goehlich excused for virtual call Andreas Mehl Andreas Goertz Corteva Mamadou Kane Mboup FMC Henry Ngugi Sumitomo Yuichi Matsuzaki Yves Senechal no participation in virtual call Ippei Uemura Syngenta Stefano Torriani Paolo Galli Irina Metaeva Helge Sierotzki Venue of the annual meeting: Lindner Congress Hotel, Frankfurt Hosting organization: FRAC/Crop Life International Disclaimer The technical information contained in the global guidelines/the website/the publication/the minutes is provided to CropLife International/RAC members, non- members, the scientific community and a broader public audience. While CropLife International and the RACs make every effort to present accurate and reliable information in the guidelines, CropLife International and the RACs do not guarantee the accuracy, completeness, efficacy, timeliness, or correct sequencing of such information. CropLife International and the RACs assume no responsibility for consequences resulting from the use of their information, or in any respect for the content of such information, including but not limited to errors or omissions, the accuracy or reasonableness of factual or scientific assumptions, studies or conclusions. Inclusion of active ingredients and products on the RAC Code Lists is based on scientific evaluation of their modes of action; it does not provide any kind of testimonial for the use of a product or a judgment on efficacy. -

Hungary: an Election in Question

To: Schmoozers From: Kim Lane Scheppele Re: Elections and Regrets 16 February 2014 I had hoped to join you all in beautiful downtown Baltimore, but I can’t come next weekend. The reason why I can’t is connected to the ticket I’m submitting anyhow. The Hungarian election is 6 April and I’m working flat out on things connected to that election. My ticket explains the new Hungarian election system, which I argue is rigged to favor the governing party. Hence the length: you can’t make an accusation like that without giving evidence. So, in a series of five blog posts that will (I hope) appear on the Krugman blog, I have laid out why I think that the opposition can’t win unless it gets far more than a majority of the votes. For those of you who haven’t been following Hungary, this new election system is par for the course. The government elected in 2010 has been on a legal rampage, remaking the whole legal order with one key purpose in mind: to keep itself in power for the foreseeable future. Toward that end, the government pushed through a new constitution plus five constitutional amendments and 834 other laws (including a new civil code, criminal code and more). As I have been documenting for the last several years, the governing party is expert at designing complex legal orders to achieve very particular results. For my writings on this, see http://lapa.princeton.edu/newsdetail.php?ID=63 . So my dissection of the new Hungarian electoral framework is what I’m submitting as my ticket for the Schmooze. -

From a Suppressed Anti-Communist Dissident Movement to a Governing Party: the Transformations of FIDESZ in Hungary

CORVINUS JOURNAL OF SOCIOLOGY AND SOCIAL POLICY Vol.2 (2011) 2, 47–66 FORUM FROM A SUPPRESSED ANTI-COMMUNIST DISSIDENT MOVEMENT TO A GOVERNING PARTY: THE TRANSFORMATIONS OF FIDESZ IN HUNGARY MÁTÉ SZABÓ 1 ABSTR A CT FIDESZ, as an outlawed protest movement of the Kádár era, has preserved their specific type of “outlawed and clandestine” political tradition and identity. A strong anti-communism, a popular mobilizing strategy and an atmosphere of hatred towards the agents of Hungary’s communist past remained within the political culture of the party from the suppressed underground movement. The political generation of leading activists, including current Prime Minister Viktor Orbán, has been socialized in the “underground” of the eighties. The experience of “being outlawed” under the Communist system has had long- lasting effects on them. The “myths”, symbols, and “fights” of the suppressed protest movements keep themselves alive in the new political culture in the present goals and strategies of FIDESZ-MPP. The former protest movement transformed itself into a minority party with liberal affiliations in the new parliament of 1990. However, as the Hungarian Liberal Party (SZDSZ) moved into a governing alliance with the successor to the Communist party, FIDESZ moved to the right, becoming its leading force. Competition between five centre-right parties led to FIDESZ’s control as the leader of a centre-right government (1998-2002). While the socialists (MSZP) and liberals (SZDSZ) became governing forces twice (2002- 2010), FIDESZ became a mobilizing populist party, gaining hegemony within the parliamentary and extra-parliamentary opposition. The economic and financial crisis assisted FIDESZ in mobilizing protest, leading the FIDESZ-KDNP alliance to a two–thirds majority victory in the 2010 elections. -

Hungary Country Report BTI 2018

BTI 2018 Country Report Hungary This report is part of the Bertelsmann Stiftung’s Transformation Index (BTI) 2018. It covers the period from February 1, 2015 to January 31, 2017. The BTI assesses the transformation toward democracy and a market economy as well as the quality of political management in 129 countries. More on the BTI at http://www.bti-project.org. Please cite as follows: Bertelsmann Stiftung, BTI 2018 Country Report — Hungary. Gütersloh: Bertelsmann Stiftung, 2018. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Contact Bertelsmann Stiftung Carl-Bertelsmann-Strasse 256 33111 Gütersloh Germany Sabine Donner Phone +49 5241 81 81501 [email protected] Hauke Hartmann Phone +49 5241 81 81389 [email protected] Robert Schwarz Phone +49 5241 81 81402 [email protected] Sabine Steinkamp Phone +49 5241 81 81507 [email protected] BTI 2018 | Hungary 3 Key Indicators Population M 9.8 HDI 0.836 GDP p.c., PPP $ 26681 Pop. growth1 % p.a. -0.3 HDI rank of 188 43 Gini Index 30.9 Life expectancy years 76.0 UN Education Index 0.854 Poverty3 % 1.0 Urban population % 71.7 Gender inequality2 0.252 Aid per capita $ - Sources (as of October 2017): The World Bank, World Development Indicators 2017 | UNDP, Human Development Report 2016. Footnotes: (1) Average annual growth rate. (2) Gender Inequality Index (GII). (3) Percentage of population living on less than $3.20 a day at 2011 international prices. Executive Summary Although leaders of hybrid regimes do not necessarily aim to dismantle the framework of democratic institutions in their country, they do seek to place constraints on liberal democracy. -

Factsheet1: the Hungarian National Assembly

Directorate-General for the Presidency Directorate for Relations with National Parliaments Factsheet1: The Hungarian National Assembly 1. At a glance Hungary is a republic and a parliamentary democracy. The Hungarian National Assembly (Országgyűlés) is a unicameral body. The 199 Members of the National Assembly are directly elected by the citizens being at least 18 years old. Elections to the National Assembly must take place every four years at the latest, and are based on the principles of proportional representation. In May 2014, last elections, 106 Members were elected in individual voting districts while 93 Members were elected from lists at national-level, which could be put forward by a political party or a national minority. The Assembly includes 14 standing committees, which debate and report on bills and supervise the work of ministers. In addition to them there are two special committees with special tasks, powers and structure. The Committee on Legislation compiles proposed amendments submitted by committees into a summary and decides which of them will come before the National Assembly for a vote. One special committee is dedicated to the spokespersons of the 13 minorities (nationality advocates) present in Hungary. The current Hungarian government under Prime Minister Mr Viktor Orbán (FIDESZ/EPP) is composed of the FIDESZ/EPP - KDNP/EPP coalition. The current President of Hungary is Mr János Áder, a former MEP of FIDESZ/EPP. 2. Composition Results of the parliamentary elections on 6 April 2014* Party EP affiliation Election -

Public Opinion in Hungary

Public Opinion in Hungary March 2-8, 2017 Detailed Methodology • The survey was conducted on behalf of the Center for Insights in Survey Research by Ipsos Hungary Zrt. • Data was collected between March 2 and March 8, 2017 through face-to-face interviews. • The total number of interviews was 1,000. • Sample size: Tot a l population (n=1,000). • Margin of error: Plus or minus 3.25 percent with 95 percent confidence level. • The sample is comprised of Hungarian residents aged 18 years and older. • Regions included in the sample are: Central Hungary; Central Transdanubia; Western Transdanubia; Southern Transdanubia; Northern Hungary; Northern Great Plain; and the Southern Great Plain. The sample includes both urban and rural inhabitants. Inhabitants of poorly accessible, remote parts of the country (comprising approximately 1% percent of the population) were excluded from the sample. • The sample design was a three-stage, random sample. • Stage One: Primary sampling unit—settlements • Stage Two: Secondary sampling unit—addresses • Stage Three: Tertiary sampling unit—respondent (selected individuals within randomly selected address by using quotas based on age and gender). • Figures in charts and tables may not add to up 100 percent due to rounding error and/or multiple choice answers. 2 Glossary of Hungarian Political Parties • Fidesz-MPSZ: Fidesz-Hungarian Civic Alliance • Jobbik: Movement for Better Hungary • MSZP: Hungarian Socialist Party • DK: Democratic Coalition • LMP: Politics Can Be Different • Együtt: Together-Party for a New Era -

Outgoing Chancellor Sebastian Kurz's People's Party (ÖVP) Favourite in the Snap Election in Austria on 29Th September Next

GENERAL ELECTION IN AUSTRIA 29th September 2019 European Outgoing Chancellor Sebastian Elections Monitor Kurz’s People’s Party (ÖVP) favourite in the snap election in Corinne Deloy Austria on 29th September next Analysis 6.4 million Austrians aged at least 16 are being called leadership of the FPÖ. He was replaced by Norbert Hofer, to ballot on 29th September to elect the 183 members Transport Minister and the unlucky candidate in the last of the National Council (Nationalrat), the lower house presidential election in 2016, when he won 48.3% of the of Parliament. This election, which is being held three vote and was beaten by Alexander Van der Bellen (51.7%) years ahead of schedule, follows the dismissal of the in the second round of the election on 4th December. government chaired by Chancellor Kurz (People’s Party, ÖVP) by the National Council on 27th May last. It was the The day after the European elections, Chancellor first time in the country’s history that a government lost Sebastian Kurz was removed from office. On 3rd June, a vote of confidence (103 of the 183 MPs voted against). Brigitte Bierlein, president of the Constitutional Court, It is even more remarkable that on the day before the became the first female Chancellor in Austria’s history. vote regarding his dismissal, the ÖVP easily won the Appointed by the President of the Republic Van der Bellen, European elections on 26th May with 34.55% of the vote. she has ensured the interim as head of government. On 21st June the Austrian authorities announced that a snap This vote of no-confidence followed the broadcast, ten election would take place on 29th September. -

ENGLISH Original: GERMAN

CIO.GAL/3/17 12 January 2017 ENGLISH Original: GERMAN STATEMENT BY THE OSCE CHAIRPERSON-IN-OFFICE AND FEDERAL MINISTER FOR EUROPE, INTEGRATION AND FOREIGN AFFAIRS OF THE REPUBLIC OF AUSTRIA, HIS EXCELLENCY SEBASTIAN KURZ, AT THE 1127th (SPECIAL) MEETING OF THE OSCE PERMANENT COUNCIL 12 January 2016 Mr. Secretary General, Dear colleagues, I am pleased to be here with you today for the first time as Chairperson-in-Office of our Organization. The success of our work together has an immediate and direct impact on the security of all of us. Austria, as an active participating State and the host country of the OSCE, has always attached the utmost importance to the Organization. Austria traditionally sees its role as a bridge-builder and a place of dialogue. We seek transparency as an honest broker. More than ever in times of great challenges, in which our continent is reverting to the bloc-based thinking of the past, this is important to us. We therefore agreed to assume the Chairmanship for the second time following our Chairmanship in 2000 in order to make a contribution to restoring stability and security. I should like first of all to congratulate and thank the outgoing German Chairmanship for its efforts over the past year. The results of the Ministerial Council in Hamburg give direction to the work of our, and future, OSCE Chairmanships. In recent years, we have witnessed a resurgence of mistrust and instability. In the OSCE area, in addition to the crisis in and around Ukraine, which is a root cause of this loss of trust, there are also other conflicts that we thought belonged to the past.