1. Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

60S Hits 150 Hits, 8 CD+G Discs Disc One No. Artist Track 1 Andy Williams Cant Take My Eyes Off You 2 Andy Williams Music To

60s Hits 150 Hits, 8 CD+G Discs Disc One No. Artist Track 1 Andy Williams Cant Take My Eyes Off You 2 Andy Williams Music to watch girls by 3 Animals House Of The Rising Sun 4 Animals We Got To Get Out Of This Place 5 Archies Sugar, sugar 6 Aretha Franklin Respect 7 Aretha Franklin You Make Me Feel Like A Natural Woman 8 Beach Boys Good Vibrations 9 Beach Boys Surfin' Usa 10 Beach Boys Wouldn’T It Be Nice 11 Beatles Get Back 12 Beatles Hey Jude 13 Beatles Michelle 14 Beatles Twist And Shout 15 Beatles Yesterday 16 Ben E King Stand By Me 17 Bob Dylan Like A Rolling Stone 18 Bobby Darin Multiplication Disc Two No. Artist Track 1 Bobby Vee Take good care of my baby 2 Bobby vinton Blue velvet 3 Bobby vinton Mr lonely 4 Boris Pickett Monster Mash 5 Brenda Lee Rocking Around The Christmas Tree 6 Burt Bacharach Ill Never Fall In Love Again 7 Cascades Rhythm Of The Rain 8 Cher Shoop Shoop Song 9 Chitty Chitty Bang Bang Chitty Chitty Bang Bang 10 Chubby Checker lets twist again 11 Chuck Berry No particular place to go 12 Chuck Berry You never can tell 13 Cilla Black Anyone Who Had A Heart 14 Cliff Richard Summer Holiday 15 Cliff Richard and the shadows Bachelor boy 16 Connie Francis Where The Boys Are 17 Contours Do You Love Me 18 Creedance clear revival bad moon rising Disc Three No. Artist Track 1 Crystals Da doo ron ron 2 David Bowie Space Oddity 3 Dean Martin Everybody Loves Somebody 4 Dion and the belmonts The wanderer 5 Dionne Warwick I Say A Little Prayer 6 Dixie Cups Chapel Of Love 7 Dobie Gray The in crowd 8 Drifters Some kind of wonderful 9 Dusty Springfield Son Of A Preacher Man 10 Elvis Presley Cant Help Falling In Love 11 Elvis Presley In The Ghetto 12 Elvis Presley Suspicious Minds 13 Elvis presley Viva las vegas 14 Engelbert Humperdinck Please Release Me 15 Erma Franklin Take a little piece of my heart 16 Etta James At Last 17 Fontella Bass Rescue Me 18 Foundations Build Me Up Buttercup Disc Four No. -

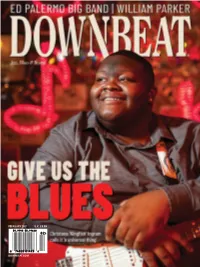

Downbeat.Com February 2021 U.K. £6.99

FEBRUARY 2021 U.K. £6.99 DOWNBEAT.COM FEBRUARY 2021 DOWNBEAT 1 FEBRUARY 2021 VOLUME 88 / NUMBER 2 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Reviews Editor Dave Cantor Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Design Assistant Will Dutton Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile Vice President of Sales 630-359-9345 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney Vice President of Sales 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Grace Blackford 630-359-9358 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Jeff Johnson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Sean J. O’Connell, Chris Walker, Josef Woodard, Scott Yanow; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Andrea Canter; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, Jennifer Odell; New York: Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Philip Freeman, Stephanie Jones, Matthew Kassel, Jimmy Katz, Suzanne Lorge, Phillip Lutz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Bill Milkowski, Allen Morrison, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian; Philadelphia: Shaun Brady; Portland: Robert Ham; San Francisco: Yoshi Kato, Denise Sullivan; Seattle: Paul de Barros; Washington, D.C.: Willard Jenkins, John Murph, Michael Wilderman; Canada: J.D. Considine, James Hale; France: Jean Szlamowicz; Germany: Hyou Vielz; Great Britain: Andrew Jones; Portugal: José Duarte; Romania: Virgil Mihaiu; Russia: Cyril Moshkow. -

September-October 2017 September-October Tyle

www.lowrey.com Wood Dale, IL 60191 Wood EZ Play Song Book Special Offers 989 AEC Drive Welcome Back! LIFE Lowrey Since L.I.F.E. has been on summer vacation, we’d like September Carole King to take this time to say hello to everyone with our “Back E-Z Play Today - Vol. 133 to Lowrey” L.I.F.E.Style Edition. Over the summer, 16 smash hits: Beautiful • Chains • Home Lowrey headquarters in Wood Dale Illinois played host to Again • I Feel the Earth Move • It’s Too Late • The Loco-Motion • (You Make Me L.I.F.E. members, students, and dealers in different events tyle Feel Like) A Natural Woman • So Far and functions. Away • Sweet Seasons • Tapestry • Up on Lacefield Music, from St. Charles and St. Louis Mis- the Roof • Where You Lead • Will You souri, visited early this summer with fifty guests! Lacefield 2017 September-October Love Me Tomorrow • You’ve Got a Friend L.I.F.E. members and students began their trip with a S • and more. quick tour of the Lowrey facility, seeing firsthand the ins Regular Price $9.99 and outs of the Lowrey headquarters. Afterwards, they Use L.I.F.E. discount code: LL09 Hal Leonard Book #: 00100306 were treated to a concert by Bil Curry and Jim Wieda, where they received a special showing and musical demon- October Walk The Line stration of the Lowrey Rialto. Lacefield staff and students E-Z Play Today had an enjoyable day in Wood Dale Illinois immersed in Channel: Youtube Check out the Lowrey Vol. -

Prestige Label Discography

Discography of the Prestige Labels Robert S. Weinstock started the New Jazz label in 1949 in New York City. The Prestige label was started shortly afterwards. Originaly the labels were located at 446 West 50th Street, in 1950 the company was moved to 782 Eighth Avenue. Prestige made a couple more moves in New York City but by 1958 it was located at its more familiar address of 203 South Washington Avenue in Bergenfield, New Jersey. Prestige recorded jazz, folk and rhythm and blues. The New Jazz label issued jazz and was used for a few 10 inch album releases in 1954 and then again for as series of 12 inch albums starting in 1958 and continuing until 1964. The artists on New Jazz were interchangeable with those on the Prestige label and after 1964 the New Jazz label name was dropped. Early on, Weinstock used various New York City recording studios including Nola and Beltone, but he soon started using the Rudy van Gelder studio in Hackensack New Jersey almost exclusively. Rudy van Gelder moved his studio to Englewood Cliffs New Jersey in 1959, which was close to the Prestige office in Bergenfield. Producers for the label, in addition to Weinstock, were Chris Albertson, Ozzie Cadena, Esmond Edwards, Ira Gitler, Cal Lampley Bob Porter and Don Schlitten. Rudy van Gelder engineered most of the Prestige recordings of the 1950’s and 60’s. The line-up of jazz artists on Prestige was impressive, including Gene Ammons, John Coltrane, Miles Davis, Eric Dolphy, Booker Ervin, Art Farmer, Red Garland, Wardell Gray, Richard “Groove” Holmes, Milt Jackson and the Modern Jazz Quartet, “Brother” Jack McDuff, Jackie McLean, Thelonious Monk, Don Patterson, Sonny Rollins, Shirley Scott, Sonny Stitt and Mal Waldron. -

The Thrill and the Truth ❏ Aretha Franklin Dies at 76 After Unchallenged Reign As Greatest Vocalist of Her Time

FRIDAY,AUG. 17, 2018 Inside: 75¢ GOP divided over Space Force. — Page 6A Vol. 90 ◆ No. 119 SERVING CLOVIS, PORTALES AND THE SURROUNDING COMMUNITIES EasternNewMexicoNews.com Los Angeles Times: Lawrence K. Ho Aretha Franklin in concert at the Microsoft Theatre in Los Angeles on Aug. 2, 2015. The thrill and the truth ❏ Aretha Franklin dies at 76 after unchallenged reign as greatest vocalist of her time. Detroit Free warning to “Think.” By Hillel Italie Press: THE ASSOCIATED PRESS Richard Lee Acknowledging the obvious, Rolling Stone ranked her first on NEW YORK — The clarity and James its list of the top 100 singers. the command. The daring and the Brown, Franklin was also named one of discipline. The thrill of her voice right, per- the 20 most important entertainers and the truth of her emotions. forms with of the 20th century by Time mag- Like the best actors and poets, Aretha azine, which celebrated her nothing came between how Franklin in “mezzo-soprano, the gospel Aretha Franklin felt and what she Detroit, growls, the throaty howls, the girl- ish vocal tickles, the swoops, the could express, between what she Michigan, in expressed and how we responded. dives, the blue-sky high notes, the January Blissful on “(You Make Me Feel blue-sea low notes. Female vocal- Like) a Natural Woman.” 1987. ists don’t get the credit as innova- Despairing on “Ain’t No Way.” tors that male instrumentalists do. Up front forever on her feminist As surely as Jimi Hendrix settled mid-20s, she recorded hundreds They should. Franklin has mas- and civil rights anthem “Respect.” arguments over who was the No. -

Standard-Auswahl

Standard-Auswahl Nummer Titel Interpret Songchip 8001 100 YEARS FIVE FOR FIGHTING Standard 10807 1000 MILES AWAY JEWEL Standard 8002 19-2000 GORILLAZ Standard 8701 20 YEARS OF SNOW REGINA SPEKTOR Standard 8004 25 MINUTES MICHAEL LEARNS TO ROCK Standard 8702 4 AM FOREVER LOSTPROPHETS Standard 8005 4 SEASONS OF LONELINESS BOYZ II MEN Standard 10808 4 TO THE FLOOR STARSAILOR Standard 8006 05:15:00 THE WHO Standard 8703 52ND STREET BILLY JOEL Standard 10050 93 MILLION MILES 30 SECONDS TO MARS Standard 8007 99 RED BALLOONS NENA Standard 8008 A CERTAIN SMILE JOHNNY MATHIS Standard 8704 A FOOL IN LOVE IKE & TINA TURNER Standard 10052 A FOOL SUCH AS I ELVIS PRESLEY Standard 9009 A LIFE ON THE OCEAN WAVE P.D. Standard 9010 A LITTLE MORE CIDER TOO P.D. Standard 8009 A LONG DECEMBER COUNTING CROWS Standard 10053 A LONG WALK JILL SCOTT Standard 8010 A LOVER'S CONCERTO SARAH VAUGHAN Standard 9011 A MAIDENS WISH P.D. Standard 8011 A MILLION LOVE SONGS TAKE THAT Standard 8705 A NATURAL WOMAN ARETHA FRANKLIN Standard 10055 A PLACE FOR MY HEAD LINKIN PARK Standard 8012 A PLACE IN THE SUN STEVIE WONDER Standard 10809 A SONG FOR THE LOVERS RICHARD ASHCROFT Standard 10057 A SONG FOR YOU THE CARPENTERS Standard 9013 A THOUSAND LEAGUES AWAY P.D. Standard 10058 A THOUSAND MILES VANESSA CARLTON Standard 9014 A WANDERING MINSTREL P.D. Standard 8013 A WHITER SHADE OF PALE PROCOL HALUM Standard 8014 A WOMAN'S WORTH ALICIA KEYS Standard 8706 A WONDERFUL DREAM THE MAJORS Standard 10059 AARON'S PARTY (COME GET IT) AARON CARTER Standard 8016 ABC THE JACKSON 5 Standard 8017 ABOUT A GIRL NIRVANA Standard 10060 ACCIDIE CAPTAIN Standard 10061 ACHY BREAKY HEART BILLY RAY CYRUS Standard 10062 ADRIENNE THE CALLING Standard 10063 AFTER ALL AL JARREAU Standard 8019 AFTER THE LOVE HAS GONE EARTH, WIND & FIRE Standard 10064 AFTERNOONS & COFFEESPOONS CRASH TEST DUMMIES Standard 8020 AGAIN LENNY KRAVITZ Standard 10810 AGAIN AND AGAIN THE BIRD AND THE BEE Standard 10066 AGE AIN'T NOTHING BUT A AALIYAH Standard 8707 NUMAIN'TBE MIRSBE HAVIN' HANK WILLIAMS, JR. -

Peggy Lee Éÿ³æ¨‚Å°ˆè¼¯ ĸ²È¡Œ (ĸ“Ⱦ‘ & Æ—¶É—´È¡¨)

Peggy Lee 音樂專輯 串行 (专辑 & 时间表) The Man I Love https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/the-man-i-love-7749873/songs Pass Me By https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/pass-me-by-7142400/songs Beauty and the Beat! https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/beauty-and-the-beat%21-4877929/songs Mirrors https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/mirrors-6874686/songs Jump for Joy https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/jump-for-joy-6311166/songs Sugar 'n' Spice https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/sugar-%27n%27-spice-7634729/songs Miss Wonderful https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/miss-wonderful-3036741/songs Close Enough for Love https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/close-enough-for-love-5135199/songs Pretty Eyes https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/pretty-eyes-7242220/songs Let's Love https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/let%27s-love-6532481/songs Blues Cross Country https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/blues-cross-country-4930454/songs Somethin' Groovy! https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/somethin%27-groovy%21-7560012/songs Things Are Swingin' https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/things-are-swingin%27-7784352/songs Latin ala Lee! https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/latin-ala-lee%21-6496491/songs Mink Jazz https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/mink-jazz-6867800/songs If You Go https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/if-you-go-5990922/songs Big $pender https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/big-%24pender-4904872/songs I Like Men! https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/i-like-men%21-5977966/songs -

Ella Fitzgerald Collection of Sheet Music, 1897-1991

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf2p300477 No online items Ella Fitzgerald collection of sheet music, 1897-1991 Finding aid prepared by Rebecca Bucher, Melissa Haley, Doug Johnson, 2015; machine-readable finding aid created by Caroline Cubé. UCLA Library Special Collections Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA, 90095-1575 (310) 825-4988 [email protected] ©2002 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Ella Fitzgerald collection of sheet PASC-M 135 1 music, 1897-1991 Title: Ella Fitzgerald collection of sheet music Collection number: PASC-M 135 Contributing Institution: UCLA Library Special Collections Language of Material: English Physical Description: 13.0 linear ft.(32 flat boxes and 1 1/2 document boxes) Date (inclusive): 1897-1991 Abstract: This collection consists of primarily of published sheet music collected by singer Ella Fitzgerald. Physical Location: Stored off-site at SRLF. Advance notice is required for access to the collection. Please contact the UCLA Library Special Collections Reference Desk for paging information. creator: Fitzgerald, Ella Restrictions on Access COLLECTION STORED OFF-SITE AT SRLF: Open for research. Advance notice required for access. Contact the UCLA Library Special Collections Reference Desk for paging information. Restrictions on Use and Reproduction Property rights to the physical object belong to the UCLA Library Special Collections. Literary rights, including copyright, are retained by the creators and their heirs. It is the responsibility of the researcher to determine who holds the copyright and pursue the copyright owner or his or her heir for permission to publish where The UC Regents do not hold the copyright. -

Zwarte Lijst 2012 - Radio 6 Soul & Jazz

Zwarte Lijst 2012 - Radio 6 Soul & Jazz 1 Otis Redding (Sittin' on) The dock of the bay 2 Bill Withers Ain't no sunshine 3 Marvin Gaye What's going on 4 Aretha Franklin Respect 5 Sam Cooke A change is gonna come 6 Kyteman Sorry 7 Curtis Mayfield Move on up 8 Amy Winehouse Back to black 9 Miles Davis So what 10 Al Green Let's stay together 11 Temptations Papa was a rolling stone 12 Nina Simone Ain't got no - I got life 13 D'Angelo Brown sugar 14 Michael Jackson Billie Jean 15 Marvin Gaye I heard it through the grapevine 16 Gregory Porter 1960 What 17 Stevie Wonder Superstition 18 Dave Brubeck Take five 19 Marvin Gaye Let's get it on 20 Erykah Badu Tyrone (live) 21 Etta James At last 22 Bill Withers Harlem 23 B.B. King The thrill is gone 24 Adele Rolling in the deep 25 James Brown Sex machine 26 Stevie Wonder As 27 Ray Charles Georgia on my mind 28 Otis Redding Try a little tenderness 29 Marvin Gaye Sexual healing 30 Curtis Mayfield Superfly 31 Bobby Womack Across 110th street 32 John Coltrane A love supreme (part 1) 33 Louis Armstrong What a wonderful world 34 Stevie Wonder I wish 35 Jamie Lidell Multiply 36 Aloe Blacc I need a dollar 37 Aretha Franklin I say a little prayer 38 Billie Holiday Strange fruit 39 Mark Ronson & Amy Winehouse Valerie 40 Bob Marley Redemption song 41 Sam & Dave Soul man 42 Ruben Hein Elephants 43 Otis Redding I've got dreams to remember 44 Ike & Tina Turner Proud Mary 45 Donny Hathaway A song for you 46 Buckshot LeFonque Another day 47 Dusty Springfield Son of a preacher man 48 Michael Jackson Don't stop 'till -

March Programming

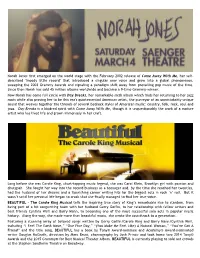

Norah Jones first emerged on the world stage with the February 2002 release of Come Away With Me, her self- described "moody little record" that introduced a singular new voice and grew into a global phenomenon, sweeping the 2003 Grammy Awards and signaling a paradigm shift away from prevailing pop music of the time. Since then Norah has sold 45 million albums worldwide and became a 9-time Grammy-winner. Now Norah has come full circle with Day Breaks, her remarkable sixth album which finds her returning to her jazz roots while also proving her to be this era's quintessential American artist, the purveyor of an unmistakably unique sound that weaves together the threads of several bedrock styles of American music: country, folk, rock, soul and jazz. Day Breaks is a kindred spirit with Come Away With Me, though it is unquestionably the work of a mature artist who has lived life and grown immensely in her craft. Long before she was Carole King, chart-topping music legend, she was Carol Klein, Brooklyn girl with passion and chutzpah. She fought her way into the record business as a teenager and, by the time she reached her twenties, had the husband of her dreams and a flourishing career writing hits for the biggest acts in rock ‘n’ roll. But it wasn’t until her personal life began to crack that she finally managed to find her true voice. BEAUTIFUL – The Carole King Musical tells the inspiring true story of King’s remarkable rise to stardom, from being part of a hit songwriting team with her husband Gerry Goffin, to her relationship with fellow writers and best friends Cynthia Weil and Barry Mann, to becoming one of the most successful solo acts in popular music history. -

Recordings by Women Table of Contents

'• ••':.•.• %*__*& -• '*r-f ":# fc** Si* o. •_ V -;r>"".y:'>^. f/i Anniversary Editi Recordings By Women table of contents Ordering Information 2 Reggae * Calypso 44 Order Blank 3 Rock 45 About Ladyslipper 4 Punk * NewWave 47 Musical Month Club 5 Soul * R&B * Rap * Dance 49 Donor Discount Club 5 Gospel 50 Gift Order Blank 6 Country 50 Gift Certificates 6 Folk * Traditional 52 Free Gifts 7 Blues 58 Be A Slipper Supporter 7 Jazz ; 60 Ladyslipper Especially Recommends 8 Classical 62 Women's Spirituality * New Age 9 Spoken 64 Recovery 22 Children's 65 Women's Music * Feminist Music 23 "Mehn's Music". 70 Comedy 35 Videos 71 Holiday 35 Kids'Videos 75 International: African 37 Songbooks, Books, Posters 76 Arabic * Middle Eastern 38 Calendars, Cards, T-shirts, Grab-bag 77 Asian 39 Jewelry 78 European 40 Ladyslipper Mailing List 79 Latin American 40 Ladyslipper's Top 40 79 Native American 42 Resources 80 Jewish 43 Readers' Comments 86 Artist Index 86 MAIL: Ladyslipper, PO Box 3124-R, Durham, NC 27715 ORDERS: 800-634-6044 M-F 9-6 INQUIRIES: 919-683-1570 M-F 9-6 ordering information FAX: 919-682-5601 Anytime! PAYMENT: Orders can be prepaid or charged (we BACK ORDERS AND ALTERNATIVES: If we are tem CATALOG EXPIRATION AND PRICES: We will honor don't bill or ship C.O.D. except to stores, libraries and porarily out of stock on a title, we will automatically prices in this catalog (except in cases of dramatic schools). Make check or money order payable to back-order it unless you include alternatives (should increase) until September. -

Aretha Franklin Looking out on the Morning Rain I Used to Feel So

A1: Natural Woman – Aretha Franklin Looking out on the morning rain I used to feel so uninspired And when I knew I had to face another day Lord, it made me feel so tired Before the day I met you, life was so unkind But your the key to my peace of mind 'Cause you make me feel You make me feel You make me feel like A natural woman (woman) When my soul was in the lost and found You came along to claim it I didn't know just what was wrong with me Till your kiss helped me name it Now I'm no longer doubtful, of what I'm living for And if I make you happy I don't need to do more 'Cause you make me feel You make me feel You make me feel like A natural woman (woman) Oh, baby, what you've done to me (what you've done to me) You make me feel so good inside (good inside) And I just want to be, close to you (want to be) You make me feel so alive You make me feel You make me feel You make me feel like A natural woman (woman) (repeat to close) A2: Across the Universe - Beatles Words are flowing out like endless rain into a paper cup, They slither while they pass, they slip away across the universe Pools of sorrow, waves of joy are drifting through my open mind, Possessing and caressing me. Jai guru deva om Nothing's gonna change my world, Nothing's gonna change my world.