Respect for a Natural Woman“

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aretha Franklin's Gendered Re-Authoring of Otis Redding's

Popular Music (2014) Volume 33/2. © Cambridge University Press 2014, pp. 185–207 doi:10.1017/S0261143014000270 ‘Find out what it means to me’: Aretha Franklin’s gendered re-authoring of Otis Redding’s ‘Respect’ VICTORIA MALAWEY Music Department, Macalester College, 1600 Grand Avenue, Saint Paul, MN 55105, USA E-mail: [email protected] Abstract In her re-authoring of Otis Redding’s ‘Respect’, Aretha Franklin’s seminal 1967 recording features striking changes to melodic content, vocal delivery, lyrics and form. Musical analysis and transcription reveal Franklin’s re-authoring techniques, which relate to rhetorical strategies of motivated rewriting, talking texts and call-and-response introduced by Henry Louis Gates, Jr. The extent of her re-authoring grants her status as owner of the song and results in a new sonic experience that can be clearly related to the cultural work the song has performed over the past 45 years. Multiple social movements claimed Franklin’s ‘Respect’ as their anthem, and her version more generally functioned as a song of empower- ment for those who have been marginalised, resulting in the song’s complex relationship with feminism. Franklin’s ‘Respect’ speaks dialogically with Redding’s version as an answer song that gives agency to a female perspective speaking within the language of soul music, which appealed to many audiences. Introduction Although Otis Redding wrote and recorded ‘Respect’ in 1965, Aretha Franklin stakes a claim of ownership by re-authoring the song in her famous 1967 recording. Her version features striking changes to the melodic content, vocal delivery, lyrics and form. -

Aretha Franklin (Sweet Sweet Baby) Since You've Been Gone / Ain't No Way Mp3, Flac, Wma

Aretha Franklin (Sweet Sweet Baby) Since You've Been Gone / Ain't No Way mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Funk / Soul Album: (Sweet Sweet Baby) Since You've Been Gone / Ain't No Way Country: US Released: 1968 Style: Soul MP3 version RAR size: 1994 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1927 mb WMA version RAR size: 1129 mb Rating: 4.9 Votes: 309 Other Formats: ASF VQF MP4 MP1 AHX MP3 DMF Tracklist Hide Credits (Sweet Sweet Baby) Since You've Been Gone A 2:18 Written-By – Aretha Franklin, Ted White Ain't No Way B 4:12 Written-By – Carolyn Franklin Companies, etc. Distributed By – Atlantic Record Sales Published By – 14th Hour Music Published By – Cotillion Music Pressed By – Plastic Products Notes From Atlantic LP 8176. Barcode and Other Identifiers Matrix / Runout (Side A Label): A-13635-PL Matrix / Runout (Side B Label): A-13657-PL Rights Society: BMI Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Aretha (Sweet Sweet Baby) Since You've 45-2486 Atlantic 45-2486 US 1968 Franklin Been Gone (7", Single, Pla) Aretha (Sweet Sweet Baby) Since You've OS 13058 Atlantic OS 13058 US Unknown Franklin Been Gone / Ain't No Way (7", RE) Aretha (Sweet Sweet Baby) Since You've 45-2486 Atlantic 45-2486 US 1968 Franklin Been Gone (7", Single) Aretha (Sweet Sweet Baby) Since You've AT 2486X Atlantic AT 2486X Canada 1968 Franklin Been Gone (7", Single) Aretha (Sweet Sweet Baby) Since You've 584172 Atlantic 584172 UK 1968 Franklin Been Gone (7", Single, Sol) Related Music albums to (Sweet Sweet Baby) Since You've Been Gone / Ain't No Way by Aretha Franklin 1. -

KMP LIST E:\New Songs\New Videos\Eminem\ Eminem

_KMP_LIST E:\New Songs\New videos\Eminem\▶ Eminem - Survival (Explicit) - YouTube.mp4▶ Eminem - Survival (Explicit) - YouTube.mp4 E:\New Songs\New videos\Akon\akon\blame it on me.mpgblame it on me.mpg E:\New Songs\New videos\Akon\akon\I Just had.mp4I Just had.mp4 E:\New Songs\New videos\Akon\akon\Shut It Down.flvShut It Down.flv E:\New Songs\New videos\Akon\03. I Just Had Sex (Ft. Akon) (www.SongsLover.com). mp303. I Just Had Sex (Ft. Akon) (www.SongsLover.com).mp3 E:\New Songs\New videos\Akon\akon - mr lonely(2).mpegakon - mr lonely(2).mpeg E:\New Songs\New videos\Akon\Akon - Music Video - Smack That (feat. eminem) (Ram Videos).mpgAkon - Music Video - Smack That (feat. eminem) (Ram Videos).mpg E:\New Songs\New videos\Akon\Akon - Right Now (Na Na Na) - YouTube.flvAkon - Righ t Now (Na Na Na) - YouTube.flv E:\New Songs\New videos\Akon\Akon Ft Eminem- Smack That-videosmusicalesdvix.blog spot.com.mkvAkon Ft Eminem- Smack That-videosmusicalesdvix.blogspot.com.mkv E:\New Songs\New videos\Akon\Akon ft Snoop Doggs - I wanna luv U.aviAkon ft Snoop Doggs - I wanna luv U.avi E:\New Songs\New videos\Akon\Akon ft. Dave Aude & Luciana - Bad Boy Official Vid eo (New Song 2013) HD.MP4Akon ft. Dave Aude & Luciana - Bad Boy Official Video (N ew Song 2013) HD.MP4 E:\New Songs\New videos\Akon\Akon ft.Kardinal Offishall & Colby O'Donis - Beauti ful ---upload by Manoj say thanx at [email protected] ft.Kardinal Offish all & Colby O'Donis - Beautiful ---upload by Manoj say thanx at [email protected] om.mkv E:\New Songs\New videos\Akon\akon-i wanna love you.aviakon-i wanna love you.avi E:\New Songs\New videos\Akon\David Guetta feat. -

Aretha Franklin Discography Torrent Download Aretha Franklin Discography Torrent Download

aretha franklin discography torrent download Aretha franklin discography torrent download. Completing the CAPTCHA proves you are a human and gives you temporary access to the web property. What can I do to prevent this in the future? If you are on a personal connection, like at home, you can run an anti-virus scan on your device to make sure it is not infected with malware. If you are at an office or shared network, you can ask the network administrator to run a scan across the network looking for misconfigured or infected devices. Another way to prevent getting this page in the future is to use Privacy Pass. You may need to download version 2.0 now from the Chrome Web Store. Cloudflare Ray ID: 67d32277da864db8 • Your IP : 188.246.226.140 • Performance & security by Cloudflare. Aretha franklin discography torrent download. Completing the CAPTCHA proves you are a human and gives you temporary access to the web property. What can I do to prevent this in the future? If you are on a personal connection, like at home, you can run an anti-virus scan on your device to make sure it is not infected with malware. If you are at an office or shared network, you can ask the network administrator to run a scan across the network looking for misconfigured or infected devices. Another way to prevent getting this page in the future is to use Privacy Pass. You may need to download version 2.0 now from the Chrome Web Store. Cloudflare Ray ID: 67d322789d5f4e08 • Your IP : 188.246.226.140 • Performance & security by Cloudflare. -

60S Hits 150 Hits, 8 CD+G Discs Disc One No. Artist Track 1 Andy Williams Cant Take My Eyes Off You 2 Andy Williams Music To

60s Hits 150 Hits, 8 CD+G Discs Disc One No. Artist Track 1 Andy Williams Cant Take My Eyes Off You 2 Andy Williams Music to watch girls by 3 Animals House Of The Rising Sun 4 Animals We Got To Get Out Of This Place 5 Archies Sugar, sugar 6 Aretha Franklin Respect 7 Aretha Franklin You Make Me Feel Like A Natural Woman 8 Beach Boys Good Vibrations 9 Beach Boys Surfin' Usa 10 Beach Boys Wouldn’T It Be Nice 11 Beatles Get Back 12 Beatles Hey Jude 13 Beatles Michelle 14 Beatles Twist And Shout 15 Beatles Yesterday 16 Ben E King Stand By Me 17 Bob Dylan Like A Rolling Stone 18 Bobby Darin Multiplication Disc Two No. Artist Track 1 Bobby Vee Take good care of my baby 2 Bobby vinton Blue velvet 3 Bobby vinton Mr lonely 4 Boris Pickett Monster Mash 5 Brenda Lee Rocking Around The Christmas Tree 6 Burt Bacharach Ill Never Fall In Love Again 7 Cascades Rhythm Of The Rain 8 Cher Shoop Shoop Song 9 Chitty Chitty Bang Bang Chitty Chitty Bang Bang 10 Chubby Checker lets twist again 11 Chuck Berry No particular place to go 12 Chuck Berry You never can tell 13 Cilla Black Anyone Who Had A Heart 14 Cliff Richard Summer Holiday 15 Cliff Richard and the shadows Bachelor boy 16 Connie Francis Where The Boys Are 17 Contours Do You Love Me 18 Creedance clear revival bad moon rising Disc Three No. Artist Track 1 Crystals Da doo ron ron 2 David Bowie Space Oddity 3 Dean Martin Everybody Loves Somebody 4 Dion and the belmonts The wanderer 5 Dionne Warwick I Say A Little Prayer 6 Dixie Cups Chapel Of Love 7 Dobie Gray The in crowd 8 Drifters Some kind of wonderful 9 Dusty Springfield Son Of A Preacher Man 10 Elvis Presley Cant Help Falling In Love 11 Elvis Presley In The Ghetto 12 Elvis Presley Suspicious Minds 13 Elvis presley Viva las vegas 14 Engelbert Humperdinck Please Release Me 15 Erma Franklin Take a little piece of my heart 16 Etta James At Last 17 Fontella Bass Rescue Me 18 Foundations Build Me Up Buttercup Disc Four No. -

SOCI 360 Social Movements Artist: Aretha Franklin Song: Think Album: Aretha Now (1968)

SOCI 360 SociAL Movements And Community Change Professor Kurt Reymers, Ph.D. sociology.morrisville.edu You better think (think) Artist: Aretha Franklin Think about what you’re tryin’ to do to me Yeah think (think, think) Song: Think Let your mind go, let yourself be free… Album: Aretha Now (1968) Oh freedom (freedom) THEME: “Thought=Choice=Freedom” Let’s have some freedom (freedom) Oh freedom Yeah freedom (yeah) You need me, I need you Without each other there ain’t nothing we can do You got to have freedom (freedom) Oh freedom (freedom) You need some freedom Oh freedom You got to have Hey! think about it You! think about it 1 K. Social Movement Leaders 1. Orienting Questions: • What social processes are involved in the emergence of leaders in social movements? • What social factors– all apart from personality and leadership style – affect the likelihood that one or another person is elevated to that position? • How do leaders gain legitimate authority in social movements once they attain that position? • Is leadership democratic, autocratic, charismatic? • What are the different types of functional roles that leaders fill? • Are their different levels of leadership, each with specific goals and spheres of influence? • How are differences in opinion over goals, tactics, and overall strategy – which invariably occur – managed? K. Social Movement Leaders 2. a. Leaders are critical to social movements, because they: • inspire commitment, • mobilize resources, • create and recognize opportunities, • devise strategies frame demands, and • influence outcomes. Any approach to leadership in social movements must examine the actions of leaders within structural contexts that both limit and facilitate opportunities, recognize the different levels of leadership, and understand the various functional roles filled by different types of movement leaders at different stages in movement development. -

Examensarbete Kandidatnivå Musikproduktionsanalys Av Avicii’S Inspelningar

Examensarbete kandidatnivå Musikproduktionsanalys av Avicii’s inspelningar Författare: Robin Granqvist Handledare: Sten Sundin Seminarieexaminator: Fil Dr David Thyrén Formell kursexaminator: Thomas Florén Ämne/huvudområde: Ljud- och musikproduktion Kurskod: LP2009 Poäng:15 hp Termin: HT2018 Examinationsdatum: 19-01-18 Vid Högskolan Dalarna finns möjlighet att publicera examensarbetet i fulltext i DiVA. Publiceringen sker open access, vilket innebär att arbetet blir fritt tillgängligt att läsa och ladda ned på nätet. Därmed ökar spridningen och synligheten av examensarbetet. Open access är på väg att bli norm för att sprida vetenskaplig information på nätet. Högskolan Dalarna rekommenderar såväl forskare som studenter att publicera sina arbeten open access. Jag/vi medger publicering i fulltext (fritt tillgänglig på nätet, open access): Ja Abstract Intresset för Avicii’s musik har under många år varit mycket stort över hela världen. Från att ha börjat som en ”bedroom producer” till att spela sin musik på scener världen över har han blivit en legend inom den elektroniska dansmusiken. Men vilka byggstenar och tekniker använder han sig av? Syftet med denna uppsats är att ta reda på hörbara kännetecken i Avicii’s musik och få en bättre förståelse för hur en framgångsrik producent skapar och bygger upp sin musik, både musikaliskt och produktionsmässigt. Avicii’s produktioner är speciellt intressanta eftersom de tenderar att innehålla både elektroniska och akustiska element. I undersökningen används musikanalys som metod där fyra av hans produktioner har analyserats med hjälp av bl.a. ljudhändelse- beskrivningar och detaljerade analyser av olika musikaliska och produktionstekniska egenskaper. Detta har gett ett resultat som visar på att det finns flera likheter mellan de olika produktionerna i bl.a. -

Cadillox TOP 100

Basic Album Inventory A check list of best selling pop albums other than those appearing on the CASH BOX Top 100 Album chart. Feature is designed to callwholesalers' & retailers' attention to key catalog, top steady selling LP's, as well as recent chart hits still going strong in sales. Information is supplied by manufacturers. Thisis a weekly revolving bit presented in alphabetical order.Itis advised that this card be kept until the list returns to this alphabetical section. ATLANTIC-ATCO AUDIO FIDELITY Banda Taurina The Brave Bulls Vol. 1 5801 Super Hits Various Artists SD 501 Banda Taurina Plaza De Toros! Vol. 2 5817 Young Rascals Young Rascals SD 8123 Banda Taurina Torero! Vol. 3 5818 Young Rascas Collections SD 8134 Banda Taurina Bullring! Vol. 4 5835 Aretha Franklin I Never Loved A Man The Way ILove You SD 8139 Steam & Diesel Railroad Sounds 5843 Young Rascals Groovin' SD 8148 Oscar Brand Series Vol. 1 to Vol. 8 Flip Wilson Cowboys & Colored People SD 8149 Al Hirt Al Hirt Swingin' Dixie Vol. 2 5878 Aretha Franklin Aretha Arrives SD 8150 Al Melgard Chicago Stadium Organ 5887 Wilson Pickett The Best Of Wilson Pickett SD 8151 Dukes of Dixieland Carnegie Hall 5918 The Rascals Once Upon A Dream SD 8169 Bakkar Dances of Port Said, Vol. 5 5922 Wilson Pickett I'm In Love SD 8175 Louis Armstrong Louie & Dukes of Dixieland 5924 Aretha Franklin Lady Soul SD 8176 Jo Basile, Accordion Rio With Love 5939 Sergio Mendes Sergio Mendes' Favorite Things SD 8177 Jo Basile & Orch Moscow With Love 5940 Flip Wilson Flip Wilson, You Devil You SD 8179 Jo Basile & Orch Mexico With Love 5946 Percy Sledge Take Time To Know Her SD 8180 Jo Basile Acapulco With Love 5947 Wilson Pickett The Midnight Mover SD 8183 Dukes of Dixieland Best of the Dukes of Dixieland 5956 Aretha Franklin Aretha Now SD 8186 Circus Carnival Calliope 5958 Various Artists The Super Hits, Vol. -

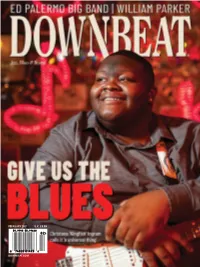

Downbeat.Com February 2021 U.K. £6.99

FEBRUARY 2021 U.K. £6.99 DOWNBEAT.COM FEBRUARY 2021 DOWNBEAT 1 FEBRUARY 2021 VOLUME 88 / NUMBER 2 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Reviews Editor Dave Cantor Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Design Assistant Will Dutton Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile Vice President of Sales 630-359-9345 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney Vice President of Sales 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Grace Blackford 630-359-9358 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Jeff Johnson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Sean J. O’Connell, Chris Walker, Josef Woodard, Scott Yanow; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Andrea Canter; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, Jennifer Odell; New York: Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Philip Freeman, Stephanie Jones, Matthew Kassel, Jimmy Katz, Suzanne Lorge, Phillip Lutz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Bill Milkowski, Allen Morrison, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian; Philadelphia: Shaun Brady; Portland: Robert Ham; San Francisco: Yoshi Kato, Denise Sullivan; Seattle: Paul de Barros; Washington, D.C.: Willard Jenkins, John Murph, Michael Wilderman; Canada: J.D. Considine, James Hale; France: Jean Szlamowicz; Germany: Hyou Vielz; Great Britain: Andrew Jones; Portugal: José Duarte; Romania: Virgil Mihaiu; Russia: Cyril Moshkow. -

Ruth Frankel Professor Swedberg CAS WS214 May 2, 2013 Carole

Ruth Frankel Professor Swedberg CAS WS214 May 2, 2013 Carole King: A Consequential Female Artist in Achievement and Message Carole King, a Brooklyn born singersongwriter, most associated with the music of the 1960s and 1970s, is significant in that she, according to her biographer James Perone, “almost singlehandedly opened the doors of popular music songwriting to women” (1). She also became the first female artist in American popular music in complete control of her own work. Her writing was prolific. She has written 500 copyrighted songs throughout her career and has had tremendous commercial success (Havranek 236). King’s greatest success was the release of the 1973 album Tapestry, which remained on the charts for 302 weeks (Perone 6). Though her cultural impact is often underappreciated, Carole King has been an important contributor to advancement of women in the music industry and a positive role model to the female audiences of her generation. It is even hard to find academic sources reflecting the success and cultural attributions of King. Overall, it appears that sexism has faded the memory of Carole King’s contribution to women in music. Again and again, King impact has not been recognized or remembered. For example, in the book Go, Girl, Go!: The Women’s Revolution in Music by James Dickerson, King’s name is mentioned only once. Dickerson writes, “Carly Simon and Carole King were the two most successful singersongwriters of the decade, and of the two, it was Carly who was dazzling the world with her toothy smile and sexy album covers” (77). -

Recorded Jazz in the 20Th Century

Recorded Jazz in the 20th Century: A (Haphazard and Woefully Incomplete) Consumer Guide by Tom Hull Copyright © 2016 Tom Hull - 2 Table of Contents Introduction................................................................................................................................................1 Individuals..................................................................................................................................................2 Groups....................................................................................................................................................121 Introduction - 1 Introduction write something here Work and Release Notes write some more here Acknowledgments Some of this is already written above: Robert Christgau, Chuck Eddy, Rob Harvilla, Michael Tatum. Add a blanket thanks to all of the many publicists and musicians who sent me CDs. End with Laura Tillem, of course. Individuals - 2 Individuals Ahmed Abdul-Malik Ahmed Abdul-Malik: Jazz Sahara (1958, OJC) Originally Sam Gill, an American but with roots in Sudan, he played bass with Monk but mostly plays oud on this date. Middle-eastern rhythm and tone, topped with the irrepressible Johnny Griffin on tenor sax. An interesting piece of hybrid music. [+] John Abercrombie John Abercrombie: Animato (1989, ECM -90) Mild mannered guitar record, with Vince Mendoza writing most of the pieces and playing synthesizer, while Jon Christensen adds some percussion. [+] John Abercrombie/Jarek Smietana: Speak Easy (1999, PAO) Smietana -

September-October 2017 September-October Tyle

www.lowrey.com Wood Dale, IL 60191 Wood EZ Play Song Book Special Offers 989 AEC Drive Welcome Back! LIFE Lowrey Since L.I.F.E. has been on summer vacation, we’d like September Carole King to take this time to say hello to everyone with our “Back E-Z Play Today - Vol. 133 to Lowrey” L.I.F.E.Style Edition. Over the summer, 16 smash hits: Beautiful • Chains • Home Lowrey headquarters in Wood Dale Illinois played host to Again • I Feel the Earth Move • It’s Too Late • The Loco-Motion • (You Make Me L.I.F.E. members, students, and dealers in different events tyle Feel Like) A Natural Woman • So Far and functions. Away • Sweet Seasons • Tapestry • Up on Lacefield Music, from St. Charles and St. Louis Mis- the Roof • Where You Lead • Will You souri, visited early this summer with fifty guests! Lacefield 2017 September-October Love Me Tomorrow • You’ve Got a Friend L.I.F.E. members and students began their trip with a S • and more. quick tour of the Lowrey facility, seeing firsthand the ins Regular Price $9.99 and outs of the Lowrey headquarters. Afterwards, they Use L.I.F.E. discount code: LL09 Hal Leonard Book #: 00100306 were treated to a concert by Bil Curry and Jim Wieda, where they received a special showing and musical demon- October Walk The Line stration of the Lowrey Rialto. Lacefield staff and students E-Z Play Today had an enjoyable day in Wood Dale Illinois immersed in Channel: Youtube Check out the Lowrey Vol.