John Hoyland: the Making and Sustaining of a Career - 1960-82

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Work in Progress (1999.03.07)

_________________________________________________________________ WORK IN PROGRESS by Cliff Holden ______________________________ Hazelridge School of Painting Pl. 92 Langas 31193 Sweden www.cliffholden.co.uk copyright © CLIFF HOLDEN 2011 2 for Lisa 3 4 Contents Foreword 7 1 My Need to Paint 9 2 The Borough Group 13 3 The Stockholm Exhibition 28 4 Marstrand Designers 40 5 Serigraphy and Design 47 6 Relating to Clients 57 7 Cultural Exchange 70 8 Bomberg's Legacy 85 9 My Approach to Painting 97 10 Teaching and Practice 109 Joseph's Questions 132 5 6 Foreword “This is the commencement of a recording made by Cliff Holden on December 12, 1992. It is my birthday and I am 73 years old. ” It is now seven years since I made the first of the recordings which have been transcribed and edited to make the text of this book. I was persuaded to make these recordings by my friend, the art historian, Joseph Darracott. We had been friends for over forty years and finally I accepted that the project which he was proposing might be feasible and would be worth attempting. And so, in talking about my life as a painter, I applied myself to the discipline of working from a list of questions which had been prepared by Joseph. During our initial discussions about the book Joseph misunderstood my idea, which was to engage in a live dialogue with the cut and thrust of question and answer. The task of responding to questions which had been typed up in advance became much more difficult to deal with because an exercise such as this lacked the kind of stimulus which a live dialogue would have given to it. -

Artists' Lives

National Life Stories The British Library 96 Euston Road London NW1 2DB Tel: 020 7412 7404 Email: [email protected] Artists’ Lives C466: Interviews complete and in-progress (at January 2019) Please note: access to each recording is determined by a signed Recording Agreement, agreed by the artist and National Life Stories at the British Library. Some of the recordings are closed – either in full or in part – for a number of years at the request of the artist. For full information on the access to each recording, and to review a detailed summary of a recording’s content, see each individual catalogue entry on the Sound and Moving Image catalogue: http://sami.bl.uk . EILEEN AGAR PATRICK BOURNE ELISABETH COLLINS IVOR ABRAHAMS DENIS BOWEN MICHAEL COMPTON NORMAN ACKROYD FRANK BOWLING ANGELA CONNER NORMAN ADAMS ALAN BOWNESS MILEIN COSMAN ANNA ADAMS SARAH BOWNESS STEPHEN COX CRAIGIE AITCHISON IAN BREAKWELL TONY CRAGG EDWARD ALLINGTON GUY BRETT MICHAEL CRAIG-MARTIN ALEXANDER ANTRIM STUART BRISLEY JOHN CRAXTON RASHEED ARAEEN RALPH BROWN DENNIS CREFFIELD EDWARD ARDIZZONE ANNE BUCHANAN CROSBY KEITH CRITCHLOW DIANA ARMFIELD STEPHEN BUCKLEY VICTORIA CROWE KENNETH ARMITAGE ROD BUGG KEN CURRIE MARIT ASCHAN LAURENCE BURT PENELOPE CURTIS ROY ASCOTT ROSEMARY BUTLER SIMON CUTTS FRANK AVRAY WILSON JOHN BYRNE ALAN DAVIE GILLIAN AYRES SHIRLEY CAMERON DINORA DAVIES-REES WILLIAM BAILLIE KEN CAMPBELL AILIAN DAY PHYLLIDA BARLOW STEVEN CAMPBELL PETER DE FRANCIA WILHELMINA BARNS- CHARLES CAREY ROGER DE GREY GRAHAM NANCY CARLINE JOSEFINA DE WENDY BARON ANTHONY CARO VASCONCELLOS -

Helios by Gillian Ayres

Helios by Gillian Ayres A talk by Amanda Phillips, Learning and Access Officer at Leeds Art Gallery This is the first of a series of short talks made for the exhibition Natural Encounters by staff and volunteers working at Leeds Art Gallery. Different voices share their ideas about one single artwork on display for our online audiences to enjoy as a personal interpretation that can add to their own. I have been asked share the first, which I’ve titled… Reading ‘Helios’ by Gillian Ayres. Up close this artwork is extraordinary. The paint is so thickly applied that it comes together in wave-top crests, with different colours meeting in mark-making that touches and then falls away. The effect blends colour in the mind’s eye, and supports the work of the imagination as it makes meaning. Helios by Gillian Ayres was produced in 1990, and is understood within the naming-systems of the art world as an Abstract painting. Currently it is displayed in the gallery’s ‘Natural Encounters’ exhibition, curated from Leeds’ art collections to explore the idea of human relationships with the natural world. The painting entered into the collection in 1991, not that long after she had painted it. In the gallery’s file of correspondence and other material linked to the artwork, is a letter that makes clear two options for purchase were on the table. Reading between the lines, it would seem that a member of the then gallery team had travelled to London in the winter of 1990 to see an exhibition of the artist’s new work, at an independent gallery owned by her then dealer. -

CV New 2020 Caronpenney (CRAFTSCOUNCIL)

Caron Penney Profile Caron Penney is a master tapestry weaver, who studied at Middlesex University and has worked in textile production for over twenty-five years. Penney creates and exhibits her own artist led tapestries for exhibition and teaches at numerous locations across the UK. Penney is also an artisanal weaver and she has manufactured the work of artists from Tracey Emin to Martin Creed. Employment DATES October 2013 - Present POSITION Freelance Sole Trader BUSINESS NAME Atelier Weftfaced CLIENTS Martin Creed, Gillian Ayres, Hauser & Wirth Gallery, Campaign for Wool, Simon Martin & Pallant House Gallery TYPE OF BUSINESS Manufacture of Tapestry DATES 2016, 2017 & 2018 POSITION Special Lecturer EMPLOYER Central Saint Martins, University of Arts London LEVEL BA Hons Textile Design TYPE OF BUSINESS Education DATES January 2014 - July 2015 POSITION Consultant EMPLOYER West Dean Tapestry Studio, W. Sussex, PO18 0QU CLIENTS Basil Beattie, Hayes Gallery, Craft Study Centre for ‘Artists Meets their Makers’ exhibition, Pallant House. TYPE OF BUSINESS Manufacture of Tapestry DATES December 2009 - October 2013 POSITION Director EMPLOYER West Dean Tapestry Studio, W. Sussex, PO18 0QU RESPONSIBILITIES The main duties included directing a team of weavers, while creating commissions, curating exhibitions, developing new innovations, assisting with fundraising, and creating a conservation and archiving procedure for the department. CLIENTS Tracey Emin, White Cube Gallery, Martin Creed, Hauser & Wirth Gallery, Historic Scotland. TYPE OF BUSINESS Manufacture of Textiles/Tapestry DATES 2000 - Present POSITION Short Course Tutor EMPLOYERS Fashion and Textiles Museum, Ashmolean Museum, Morley College, Hauser & Wirth Somerset, Ditchling Museum , Fleming Collection, Charleston Farmhouse, West Dean College, William Morris Gallery, and many others. -

Ivon Hitchens & His Lasting Influence

Ivon Hitchens & his lasting influence Ivon Hitchens & his lasting influence 29 June - 27 July 2019 An exhibition of works by Ivon Hitchens (1893-1979) and some of those he influenced 12 Northgate, Chichester West Susssex PO19 1BA +44 (0)1243 528401 / 07794 416569 [email protected] www.candidastevens.com Open Wed - Sat 10-5pm & By appointment “But see Hitchens at full pitch and his vision is like the weather, like all the damp vegetable colours of the English countryside and its sedgy places brushed mysteriously together and then realised. It is abstract painting of unmistakable accuracy.” – Unquiet Landscape (p.145 Christopher Neve) The work of British painter Ivon Hitchens (1893 – 1979) is much-loved for his highly distinctive style in which great swathes of colour sweep across the long panoramic canvases that were to define his career. He sought to express the inner harmony and rhythm of landscape, the experience, not of how things look but rather how they feel. A true pioneer of the abstracted vision of landscape, his portrayal of the English countryside surrounding his home in West Sussex would go on to form one of the key ideas of British Mod- ernism in the 20thCentury. A founding member of the Seven & Five Society, the influential group of painters and sculptors that was responsible for bringing the ideas of the European avant-garde to London in the 30s, Hitchens was progres- sive long before the evolution of his more abstracted style post-war. Early on he felt a compulsion to move away from the traditional pictorial language of art school and towards the development of a personal language. -

Studio International Magazine: Tales from Peter Townsend’S Editorial Papers 1965-1975

Studio International magazine: Tales from Peter Townsend’s editorial papers 1965-1975 Joanna Melvin 49015858 2013 Declaration of authorship I, Joanna Melvin certify that the worK presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this is indicated in the thesis. i Tales from Studio International Magazine: Peter Townsend’s editorial papers, 1965-1975 When Peter Townsend was appointed editor of Studio International in November 1965 it was the longest running British art magazine, founded 1893 as The Studio by Charles Holme with editor Gleeson White. Townsend’s predecessor, GS Whittet adopted the additional International in 1964, devised to stimulate advertising. The change facilitated Townsend’s reinvention of the radical policies of its founder as a magazine for artists with an international outlooK. His decision to appoint an International Advisory Committee as well as a London based Advisory Board show this commitment. Townsend’s editorial in January 1966 declares the magazine’s aim, ‘not to ape’ its ancestor, but ‘rediscover its liveliness.’ He emphasised magazine’s geographical position, poised between Europe and the US, susceptible to the influences of both and wholly committed to neither, it would be alert to what the artists themselves wanted. Townsend’s policy pioneered the magazine’s presentation of new experimental practices and art-for-the-page as well as the magazine as an alternative exhibition site and specially designed artist’s covers. The thesis gives centre stage to a British perspective on international and transatlantic dialogues from 1965-1975, presenting case studies to show the importance of the magazine’s influence achieved through Townsend’s policy of devolving responsibility to artists and Key assistant editors, Charles Harrison, John McEwen, and contributing editor Barbara Reise. -

Parviz Tanavoli Poet in Love

1970s-2011 Works from the Artist ’s Collection Parviz Tanavoli Poet in Love Austin / Desmond Fine Art Pied Bull Yard 68/69 Great Russell St Bloomsbury London WC1B 3BN Telephone: + 44 (0)20 7242 4443 Email: gallery @austindesmond .com Web : ww w.austindesmond .com 1 The Global Vision of Parviz Tanavoli Dr David Galloway Thirty-five years have passed since my first encounter with Parviz Tanavoli in Iran: years of creation and achievement, of revolution and heartache, of exile and return. More than a friend, he was also a mentor who taught me to decipher (and cherish) some of the rich visual codes of Persian culture. Furthermore, he did so not by leading me pedantically through museums and archeological sites but simply by welcoming me to his atelier, where the language of the past was being transmuted into a vivid contemporary idiom. This vital synthesis is, without doubt, the greatest achievement of the greatest sculptor to emerge from the modern Islamic world. For decades, gifted artists from Iran or Iraq, Egypt or Morocco had studied in famous Western art centers and returned home to shoulder the burden of a seemingly irresolvable dilemma. Either they could apply their skills to the traditional arts or propagate the styles and techniques acquired in their journeyman years – at the risk of being labeled epigones. It was, of course, not merely Islamic artists who faced such a dilemma, but more generally those whose vision had initially been fostered by a powerful traditional aesthetic and were subsequently exposed to a contemporary Western form language. (The extraordinarily rich visual heritage of Iran, on the other hand, lent the choice particular urgency.) Tanavoli resolved the dilemma by embracing the arts and handicrafts of his own culture but also by literally reinventing them, passing them through the filter of his own exposure to Western movements. -

Strategic Anomalies: Art & Language in the Art School 1969-1979

Strategic Anomalies: Art & Language in the Art School 1969-1979 Dennis, M. Submitted version deposited in Coventry University’s Institutional Repository Original citation: Dennis, M. () Strategic Anomalies: Art & Language in the Art School 1969-1979. Unpublished MSC by Research Thesis. Coventry: Coventry University Copyright © and Moral Rights are retained by the author. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This item cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder(s). The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Some materials have been removed from this thesis due to Third Party Copyright. Pages where material has been removed are clearly marked in the electronic version. The unabridged version of the thesis can be viewed at the Lanchester Library, Coventry University. Strategic Anomalies: Art & Language in the Art School 1969-1979 Mark Dennis A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the University’s requirements for the Degree of Master of Philosophy/Master of Research September 2016 Library Declaration and Deposit Agreement Title: Forename: Family Name: Mark Dennis Student ID: Faculty: Award: 4744519 Arts & Humanities PhD Thesis Title: Strategic Anomalies: Art & Language in the Art School 1969-1979 Freedom of Information: Freedom of Information Act 2000 (FOIA) ensures access to any information held by Coventry University, including theses, unless an exception or exceptional circumstances apply. In the interest of scholarship, theses of the University are normally made freely available online in the Institutions Repository, immediately on deposit. -

The Scratch Orchestra and Visual Arts Michael Parsons

The Scratch Orchestra and Visual Arts Michael Parsons Leonardo Music Journal, Vol. 11, Not Necessarily "English Music": Britain's Second Golden Age. (2001), pp. 5-11. Stable URL: http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0961-1215%282001%2911%3C5%3ATSOAVA%3E2.0.CO%3B2-V Leonardo Music Journal is currently published by The MIT Press. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/about/terms.html. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/journals/mitpress.html. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. The JSTOR Archive is a trusted digital repository providing for long-term preservation and access to leading academic journals and scholarly literature from around the world. The Archive is supported by libraries, scholarly societies, publishers, and foundations. It is an initiative of JSTOR, a not-for-profit organization with a mission to help the scholarly community take advantage of advances in technology. For more information regarding JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. http://www.jstor.org Sat Sep 29 14:25:36 2007 The Scratch Orchestra and Visual Arts ' The Scratch Orchestra, formed In London in 1969 by Cornelius Cardew, Michael Parsons and Howard Skempton, included VI- sual and performance artists as Michael Parsons well as musicians and other partici- pants from diverse backgrounds, many of them without formal train- ing. -

City Research Online

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Summerfield, Angela (2007). Interventions : Twentieth-century art collection schemes and their impact on local authority art gallery and museum collections of twentieth- century British art in Britain. (Unpublished Doctoral thesis, City University, London) This is the accepted version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/17420/ Link to published version: Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] 'INTERVENTIONS: TWENTIETH-CENTURY ART COLLECTION SCIIEMES AND TIIEIR IMPACT ON LOCAL AUTHORITY ART GALLERY AND MUSEUM COLLECTIONS OF TWENTIETII-CENTURY BRITISH ART IN BRITAIN VOLUME If Angela Summerfield Ph.D. Thesis in Museum and Gallery Management Department of Cultural Policy and Management, City University, London, August 2007 Copyright: Angela Summerfield, 2007 CONTENTS VOLUME I ABSTRA.CT.................................................................................. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS •........••.••....••........•.•.•....•••.......•....•...• xi CHAPTER 1:INTRODUCTION................................................. 1 SECTION 1 THE NATURE AND PURPOSE OF PUBLIC ART GALLERIES, MUSEUMS AND THEIR ART COLLECTIONS.......................................................................... -

Generation Painting: Abstraction and British Art, 1955–65 Saturday 5 March 2016, 09:45-17:00 Howard Lecture Theatre, Downing College, Cambridge

Generation Painting: Abstraction and British Art, 1955–65 Saturday 5 March 2016, 09:45-17:00 Howard Lecture Theatre, Downing College, Cambridge 09:15-09:40 Registration and coffee 09:45 Welcome 10:00-11:20 Session 1 – Chaired by Dr Alyce Mahon (Trinity College, Cambridge) Crossing the Border and Closing the Gap: Abstraction and Pop Prof Martin Hammer (University of Kent) Fellow Persians: Bridget Riley and Ad Reinhardt Moran Sheleg (University College London) Tailspin: Smith’s Specific Objects Dr Jo Applin (University of York) 11:20-11:40 Coffee 11:40-13:00 Session 2 – Chaired by Dr Jennifer Powell (Kettle’s Yard) Abstraction between America and the Borders: William Johnstone’s Landscape Painting Dr Beth Williamson (Independent) The Valid Image: Frank Avray Wilson and the Biennial Salon of Commonwealth Abstract Art Dr Simon Pierse (Aberystwyth University) “Unity in Diversity”: New Vision Centre and the Commonwealth Maryam Ohadi-Hamadani (University of Texas at Austin) 13:00-14:00 Lunch and poster session 14:00-15:20 Session 3 – Chaired by Dr James Fox (Gonville & Caius College, Cambridge) In the Thick of It: Auerbach, Kossoff and the Landscape of Postwar Painting Lee Hallman (The Graduate Center, CUNY) Sculpture into Painting: John Hoyland and New Shape Sculpture in the Early 1960s Sam Cornish (The John Hoyland Estate) Painting as a Citational Practice in the 1960s and After Dr Catherine Spencer (University of St Andrews) 15:20-15:50 Tea break 15:50-17:00 Keynote paper and discussion Two Cultures? Patrick Heron, Lawrence Alloway and a Contested -

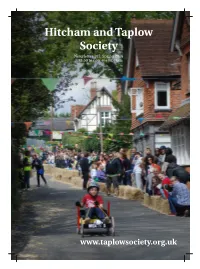

Hitcham and Taplow Society Newsletter Spring 2016

Hitcham and Taplow Society Newsletter 105: Spring 2016 £3.50 to nonmembers www.taplowsociety.org.uk Hitcham and Taplow Society Formed in 1959 to protect Hitcham, Taplow and the surrounding countryside from being spoilt by bad development and neglect. President: Eva Lipman Vice Presidents: Tony Hickman, Fred Russell, Professor Bernard Trevallion OBE Chairman: Karl Lawrence Treasurer: Myra Drinkwater Secretary: Roger Worthington Committee: Heather Fenn, Charlie Greeves, Robert Harrap, Zoe Hatch, Alastair Hill, Barrie Peroni, Nigel Smales, Louise Symons, Miv WaylandSmith Website Adviser & Newsletter Production: Andrew Findlay Contact Address: HTS, Littlemere, River Road, Taplow, SL6 0BB [email protected] 07787 556309 Cover picture: Sarah & Tony Meats' grandson Herbie during the Race to the Church (Nigel Smales) Editorial Change: the only constant? There's certainly a lot This Newsletter is a bumper edition to feature of it about. Down by the Thames, the change is a few milestones: two cherished memories of physical (see Page 7). Up in the Village, it is notsolong ago were revived recently to mark personal (see Pages 17, 18 & 19). Some changes the Queen’s 90th birthday (see Pages 9, 14 & 15) stand the tests of time (see Pages 1013 & 16). and Cedar Chase celebrates its Golden Jubilee Will the same be said for potential changes in (see Pages 1013). Buffins and Wellbank are of the pipeline (see Pages 4, 5 & 6) which claim similar vintage; perhaps they can be persuaded roots in evidenceled policymaking while to pen pieces for future editions. We are whiffing of policyled evidencemaking? delighted to welcome Amber, our youngestever The Society faces three changes.