Promise and Problems: Web Series and Independent Production in Periods of Change

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Yarns and Funny Jokes

f IMfWtMTYLIBRARY^)Of AUKJUNIA h SAMMMO ^^F -J) NEW YARNS AND COMPRISING ORIGINAL AND SELECTED MERIGAN * HUMOR WITH MANY LAUGHABLE ILLUSTRATIONS. Copyright, 1890, by EXCELSIOR PUBLISHING HOUSE. NEW YORK* EXCELSIOR PUBLISHING HOUSB, 29 & 3 1 Beekman Street EXCELSIOR PUBLISHING HOUSE, 29 &. 31 Beekman Street, New York, N. Y. PAYNE'S BUSINESS EDUCATOR AN- ED cyclopedia of the Knowl* edge necessary to the Conduct of Business, AMONG THE CONTENTS ARE: An Epitome of the Laws of the various States of the Union, alphabet- ically arranged for ready reference ; Model Business Letters and Answers ; in Lessons Penmanship ; Interest Tables ; Rules of Order for Deliberative As- semblies and Debating Societies Tables of Weights and Measures, Stand- ard and the Metric System ; lessons in Typewriting; Legal Forms for all Instruments used in Ordinary Business, such as Leases, Assignments, Contracts, etc., etc.; Dictionary of Mercantile Terms; Interest Laws of the United States; Official, Military, Scholastic, Naval, and Professional Titles used in U. S.; How to Measure Land ; in Yalue of Foreign Gold and Silver Coins the United states ; Educational Statistics of the World ; List of Abbreviations ; and Italian and Phrases Latin, French, Spanish, Words -, Rules of Punctuation ; Marks of Accent; Dictionary of Synonyms; Copyright Law of the United States, etc., etc., MAKING IN ALL THE MOST COMPLETE SELF-EDUCATOR PUBLISHED, CONTAINING 600 PAGES, BOUND IN EXTRA CLOTH. PRICE $2.00. N.B.- LIBERAL TERMS TO AGENTS ON THIS WORK. The above Book sent postpaid on receipt of price. Yar]Qs Jokes. ' ' A Natural Mistake. Well, Jim was champion quoit-thrower in them days, He's dead now, poor fellow, but Jim was a boss on throwing quoits. -

A Production Process for Developing a Web Series, Snaptv

California State University, San Bernardino CSUSB ScholarWorks Electronic Theses, Projects, and Dissertations Office of aduateGr Studies 12-2017 A PRODUCTION PROCESS FOR DEVELOPING A WEB SERIES, SNAPTV Toebey T. Caldwell Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd Part of the Acting Commons, Dramatic Literature, Criticism and Theory Commons, Other Theatre and Performance Studies Commons, Performance Studies Commons, Playwriting Commons, and the Television Commons Recommended Citation Caldwell, Toebey T., "A PRODUCTION PROCESS FOR DEVELOPING A WEB SERIES, SNAPTV" (2017). Electronic Theses, Projects, and Dissertations. 588. https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd/588 This Project is brought to you for free and open access by the Office of aduateGr Studies at CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses, Projects, and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A PRODUCTION PROCESS FOR DEVELOPING A WEB SERIES, SNAPTV A Project Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in Interdisciplinary Studies: Film Theory and Media Production by Toebey Ty Caldwell December 2017 A PRODUCTION PROCESS FOR DEVELOPING A WEB SERIES, SNAPTV A Project Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino by Toebey Ty Caldwell December 2017 Approved by: Kathryn Ervin, Committee Chair, Theatre Arts Andre Harrington, Theatre Arts C. Rod Metts, Communication Studies © 2017 Toebey Ty Caldwell ABSTRACT My project for this Interdisciplinary Master’s Program, studying Film Theories and Media Production methods, details “A Production Process for Creating a Web Series, called SNAPtv”. -

Jan-Mar 2002 High Bandwidth

I N T H I S I S S U E So You Want It In HD One on One makes the transition to 24P HD Peak Experience HD is up to the challenge with this indie feature N A T P E 2 0 0 2 The Mavericks of Multi-Camera 24P Production “The familiar look and feel of HDW-F900 HDCAM 24P CineAlta™ High Definition camcorder. The digital movie camera.* motion picture film are here.” — GEORGE LUCAS If you want to see a movie pro get future,” says Chuck Barbee, the We shot Star Wars: Episode II excited, ask George Lucas, Chuck director of photography. “The in 61 days in 5 countries in the Barbee, or Mike Figgis about Sony whole process was surprisingly Digital Electronic Cinematography. good. And compared to film, raw rain and desert heat averaging Each is using Sony tools to explore tape stock costs next to noth- new creative possibilities. 36 setups per day without a ing. This really lowers the cost “Star Wars: Episode II is our last giant of getting it in the can, which single camera problem. We have DVW-790WS Digital Betacam® camcorder. step toward Digital Cinema,” says means that more projects The gold standard found the picture quality of the in Widescreen George Lucas, describing his decision can get made.” Standard Definition. to shoot principal photography 24P Digital HD system to be with Panavision-modified Sony Mike Figgis challenges our most indistinguishable from film. HDCAM® 24P camcorders. “The basic conventions of narrative in familiar look and feel of motion Timecode, the movie that follows – George Lucas and picture film are present in this four simultaneous storylines in Rick McCallum digital 24P system. -

Podcasts and Convergent Digital Media Michael Dwyer, Arcadia University

Podcasts and Convergent Digital Media Michael Dwyer, Arcadia University What is a podcast, anyway? Is it a textual form? A genre of audio recording? A distribution method? And what was a podcast ten years ago? Are they different now from how they were then? How so? Why? Those are important questions. But it appears that media studies, as a discipline, has yet to pursue them in any sustained way. The word “podcast” has appeared in Cinema Journal in only 11 pieces, mostly in announcements and citations. In Velvet Light Trap, the word’s appeared twice. Major academic publishers like Routledge have only a few podcasting monographs, mostly of the how-to variety. Run a search on the term “podcast” on Flow and you get 41 results. A single television series like Battlestar Galactica, by contrast, returns 46 results. What might explain this relative silence from a group of scholars whose animating purpose is the study of popular media? I am reminded, as I often am, of Tim Anderson’s 2009 Velvet Light Trap essay “A Skip in the Record of Media Studies.” In it, Anderson argues that media studies' failure to fully embrace the study of sound media has "unwittingly articulated blind spots that make it unable to fully understand what is at stake today" (104). Consider, for example the roundtable prompt that animates our discussion, which articulates a desire to consider podcasts “alongside other popular forms, such as web series and online television,” but not sound media. If media studies scholars want to understand podcasts (and I think we all here sincerely do) we need to understand them in relation to media industries like radio, pop music, and sound recording as well as screen media. -

Small Business-Themed Web Series Helps Drive Extra Sales 1/2/2013

January 2013 Small business-themed Web series helps drive extra sales Client social networks. Marketing and Hiscox USA (New York) PR trades and general consum- PR agency er outlets were also pitched. Prosek Partners (New York) Campaign RESULTS Leap Year season two Hoffmann says general con- Duration sumer surveys conducted in Q3 February-September 2012 2011 and Q3 2012 revealed Budget aided brand awareness nearly $400,000 doubled. The campaign also contributed to a 35% increase in product quotes viewed and In summer 2011, Hiscox and products purchased online dur- its long-time agency Prosek The second season of Web series Leap Year attracted 2.3 million ing the same time period. viewers during its initial 10-week run from June 18 to August 20 Partners (formerly CJP Com- Brand impressions across munications), launched an social media, traditional media, original Web series called “The storyline grows in the business scenarios and men- and all video channels hit 321 Leap Year as part of a larger same way many of our target tioned general types of insur- million, up from 105 million marketing campaign to audience’s businesses grow,” ance that could help. for season one. Comparing drive awareness of the com- explains Hoffmann. Various entrepreneurs and seasons one and two, Twitter pany’s new small business Strategic partnerships, social startup experts, including Red- impressions skyrocketed from 6 insurance products. media engagement, media rela- dit cofounder Alexis Ohanian million to 24 million, and Face- The series explored chal- tions, and attendance at the and TechCrunch reporter Ryan book impressions more than lenges facing first-time entre- Mashable Connect conference Lawler, appeared in episodes doubled to 5.3 million. -

Toand Television Irrom June 25

TOAND TELEVISION IRROM JUNE 25 1tVeledrillt 44 111vot-ir Percy MILTON BERLE GRACIE ALLEN ')N McNEILL RALPH EDWARDS BIG SISTER LANNY ROSS filter Winchell Contest Winners - i (o+1) Vie, fodLut, tiA9ti otcuut SKIN -SAFE SOLITAIRI The only founda- tion- and -pawder make -up with clinicol evidence- certified by leading skin specialists from coast to coast -that it DOES NOT CLOG PORES, cause skin texture change or inflammation of hair follicle ar other gland opening. Na other liquid, powder, creom or cake "founda- tion" moke -up offers such positive proof of safety for your skin. biopsy- specimen flown by Cell Chapman. Jewels by Seaman-Schepps. See the loveliest you that you've ever seen -the minute you use Solitair cake make -up. Gives your skin a petal- smooth appearance -so flatteringly natural that you look as if you'd been born with it! Solitair is entirely different- a special feather -weight formula. Clings longer. Outlasts powder. Hides little skin faults -yet never feels mask -like, never looks "made -up." Like finest face creams, Solitair contains Lanolin to protect against dryness. Truly -you'll be lovelier with this make -up that millions prefer. No better quality. Only $1.00. Cake Make -Up * Fashion -Point Lipstick Seven new fashion -right shades Yes -the first and only lipstick with point actually shaped to curve of your lips. Applies color quicker, easier, more evenly. New, exciting "Dreamy Pink" shade - and six new reds. So creamy smooth- contains Lanolin -stays on so long. Exquisite case. $1.00 *Slanting cap with red enameled circle identifies the famous 'Fashion -Point and shows you exact (¡orí*iwnn tameGm color of lipstick inside. -

The Cybernetic Brain

THE CYBERNETIC BRAIN THE CYBERNETIC BRAIN SKETCHES OF ANOTHER FUTURE Andrew Pickering THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS CHICAGO AND LONDON ANDREW PICKERING IS PROFESSOR OF SOCIOLOGY AND PHILOSOPHY AT THE UNIVERSITY OF EXETER. HIS BOOKS INCLUDE CONSTRUCTING QUARKS: A SO- CIOLOGICAL HISTORY OF PARTICLE PHYSICS, THE MANGLE OF PRACTICE: TIME, AGENCY, AND SCIENCE, AND SCIENCE AS PRACTICE AND CULTURE, A L L PUBLISHED BY THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS, AND THE MANGLE IN PRAC- TICE: SCIENCE, SOCIETY, AND BECOMING (COEDITED WITH KEITH GUZIK). THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS, CHICAGO 60637 THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS, LTD., LONDON © 2010 BY THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. PUBLISHED 2010 PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA 19 18 17 16 15 14 13 12 11 10 1 2 3 4 5 ISBN-13: 978-0-226-66789-8 (CLOTH) ISBN-10: 0-226-66789-8 (CLOTH) Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Pickering, Andrew. The cybernetic brain : sketches of another future / Andrew Pickering. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-226-66789-8 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-226-66789-8 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Cybernetics. 2. Cybernetics—History. 3. Brain. 4. Self-organizing systems. I. Title. Q310.P53 2010 003’.5—dc22 2009023367 a THE PAPER USED IN THIS PUBLICATION MEETS THE MINIMUM REQUIREMENTS OF THE AMERICAN NATIONAL STANDARD FOR INFORMATION SCIENCES—PERMA- NENCE OF PAPER FOR PRINTED LIBRARY MATERIALS, ANSI Z39.48-1992. DEDICATION For Jane F. CONTENTS Acknowledgments / ix 1. The Adaptive Brain / 1 2. Ontological Theater / 17 PART 1: PSYCHIATRY TO CYBERNETICS 3. -

HOW to BUILD an AUDIENCE for YOUR WEB SERIES: Market, Motivate and Mobilize

HOW TO BUILD AN AUDIENCE FOR YOUR WEB SERIES: Market, Motivate and Mobilize Julie Giles A Publication of the Independent Production Fund How to Build an Audience for Your Web Series: Market, Motivate and Mobilize Publication date May 2011 Written by: Julie Giles www.greenhatdigital.com Editor: Andra Sheffer Graphic Design/Layout: Helen Prancic Version 1.0 © Copyright 2011 Independent Production Fund All right reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by an means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. Contact [email protected] Notice of Liability. The information in this book is distributed on an “as is” basis, without warranty. While every precaution has been taken in the preparation of this book, neither the author nor the publisher shall have any liability to any person or entity with respect to any liability, loss, or damage caused or alleged to be caused directly or indirectly by the instructions contained in this book or any materials or products described therein. National Library of Canada Cataloguing in Publication Data Main entry under title: How to Build an Audience for your Web Series: Market, Motivate and Mobilize Issued also in French under title: Comment bâtir un auditoire pour une websérie: Commercialiser, Motiver, Mobiliser. ISBN 978-0-9876748-0-7 Published in Canada by: Independent Production Fund 2 Carlton St., Suite 1709 4200, boul Saint-Laurent, Bureau 503 Toronto, Ontario M5B 1J3 Montréal, Québec H2W 2R2 [email protected] -

Treatise of Human Nature Book II: the Passions

Treatise of Human Nature Book II: The Passions David Hume Copyright © Jonathan Bennett 2017. All rights reserved [Brackets] enclose editorial explanations. Small ·dots· enclose material that has been added, but can be read as though it were part of the original text. Occasional •bullets, and also indenting of passages that are not quotations, are meant as aids to grasping the structure of a sentence or a thought. Every four-point ellipsis . indicates the omission of a brief passage that seems to present more difficulty than it is worth. Longer omitted passages are reported on, between [brackets], in normal-size type. First launched: June 2008 Contents Part i: Pride and humility 147 1: Division of the subject........................................................ 147 2: Pride and humility—their objects and causes......................................... 148 3: Where these objects and causes come from.......................................... 150 4: The relations of impressions and ideas............................................. 152 5: The influence of these relations on pride and humility..................................... 154 6: Qualifications to this system.................................................... 157 7: Vice and virtue........................................................... 159 8: Beauty and ugliness......................................................... 161 9: External advantages and disadvantages............................................. 164 10: Property and riches........................................................ -

An Empirical Study to Measure Fascination of Young Adults Towards Web Series

Damini Hareshkumar Gianchandani et al./ International Journal Vol. 9, Issue 5, May : 2020 for Research in Management and Pharmacy (I.F.5.944) (IJRMP) ISSN: 2320- 0901 An Empirical Study to Measure Fascination of Young Adults towards Web series DAMINI HARESHKUMAR GIANCHANDANI Research Scholar (M.Phill), Ganpat University, Kherva, Mehsana., Kherva, Gujarat, India DR. SURAJ M. SHAH Assistant Professor, Centre for Management Studies and Research, Ganpat University, Kherva, Mehsana. DR. MAHENDRA S. SHARMA Pro-Chancellor and Director General, Ganpat University, Kherva, Mehsana. Abstract: The Digital Democracy Survey defined the activity as “watching three or more episodes of a TV or web series in one sitting” (Deloitte 2015). To grab the audience towards a web series localizing of the content is the new strategy. This makes the content to be relevant and relatable to the audience and thus a large number of audience’s interest is been caught (Vijay Subramanian, 2017). But content is not the only reason why web series have been successful in grabbing the eyeballs of people, they have also made it a point to quench our thirst for diverse subject and issues. With the rise in the popularity of the Internet and improvements the accessibility and affordability of high speed broadband and streaming video technology meant that producing and distributing a web series became a feasible alternative to "traditional" series production, which was formerly mostly done for broadcast and cable TV. Most of age groups have now Turn off their television sets and tune into Web series. Here, the research objective is to measure fascination of young adults towards web series. -

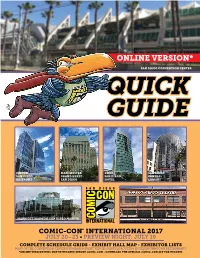

Online Version*

ONLINE VERSION* SAN DIEGO CONVENTION CENTER QUICK GUIDE HILTON MANCHESTER OMNI SAN DIEGO SAN DIEGO GRAND HYATT SAN DIEGO CENTRAL BAYFRONT SAN DIEGO HOTEL LIBRARY MARRIOTT MARQUIS SAN DIEGO MARINA COMIC-CON® INTERNATIONAL 2017 JULY 20–23 • PREVIEW NIGHT: JULY 19 COMPLETE SCHEDULE GRIDS • EXHIBIT HALL MAP • EXHIBITOR LISTS MAPS OF THE CONVENTION CENTER/PROGRAM & EVENT VENUES/SHUTTLE ROUTES & HOTELS/DOWNTOWN RESTAURANTS *ONLINE VERSION WILL NOT BE UPDATED BEFORE COMIC-CON • DOWNLOAD THE OFFICIAL COMIC-CON APP FOR UPDATES COMIC-CON INTERNATIONAL 2017 QUICK GUIDE WELCOME! to the 2017 edition of the Comic-Con International Quick Guide, your guide to the show through maps and the schedule-at-a-glance programming grids! Please remember that the Quick Guide and the Events Guide are once again TWO SEPARATE PUBLICATIONS! For an in-depth look at Comic- Con, including all the program descriptions, pick up a copy of the Events Guide in the Sails Pavilion upstairs at the San Diego Convention Center . and don’t forget to pick up your copy of the Souvenir Book, too! It’s our biggest book ever, chock full of great articles and art! CONTENTS 4 Comic-Con 2017 Programming & Event Locations COMIC-CON 5 RFID Badges • Morning Lines for Exclusives/Booth Signing Wristbands 2017 HOURS 6-7 Convention Center Upper Level Map • Mezzanine Map WEDNESDAY 8 Hall H/Ballroom 20 Maps Preview Night: 9 Hall H Wristband Info • Hall H Next Day Line Map 6:00 to 9:00 PM 10 Rooms 2-11 Line Map THURSDAY, FRIDAY, 11 Hotels and Shuttle Stops Map SATURDAY: 9:30 AM to 7:00 PM* 14-15 Marriott Marquis San Diego Marina Program Information and Maps SUNDAY: 16-17 Hilton San Diego Bayfront Program Information and Maps 9:30 AM to 5:00 PM 18-19 Manchester Grand Hyatt Program Information and Maps *Programming continues into the evening hours on 20 Horton Grand Theatre Program Information and Map Thursday through 21 San Diego Central Library Program Information and Map Saturday nights. -

The Web As Television Reimagined?

Journal of Communication Inquiry http://jci.sagepub.com/ The Web as Television Reimagined? Online Networks and the Pursuit of Legacy Media Aymar Jean Christian Journal of Communication Inquiry 2012 36: 340 DOI: 10.1177/0196859912462604 The online version of this article can be found at: http://jci.sagepub.com/content/36/4/340 Published by: http://www.sagepublications.com On behalf of: Cultural and Critical Studies Division of the Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication Additional services and information for Journal of Communication Inquiry can be found at: Email Alerts: http://jci.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts Subscriptions: http://jci.sagepub.com/subscriptions Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav Permissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav Citations: http://jci.sagepub.com/content/36/4/340.refs.html >> Version of Record - Oct 31, 2012 What is This? Downloaded from jci.sagepub.com at NORTHWESTERN UNIV LIBRARY on November 10, 2012 JCI36410.1177/0196859912462604 462604Journal of Communication InquiryChristian Journal of Communication Inquiry 36(4) 340 –356 The Web as Television © The Author(s) 2012 Reprints and permission: Reimagined? Online sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav DOI: 10.1177/0196859912462604 Networks and the http://jci.sagepub.com Pursuit of Legacy Media Aymar Jean Christian1 Abstract Television’s perceived weakness at the turn of the century opened a rhetorical and economic space for entrepreneurs eager to curate and distribute web programs. These companies introduced various forms of experimentation they associated with the advantages of digital technologies, but they also maintained continuity with television’s business practices. This dialectic between old and new, continuity and change, insiders and outsiders, reflected the instability of television as a concept and the promise of the web as an alternative.