The Web As Television Reimagined?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Uila Supported Apps

Uila Supported Applications and Protocols updated Oct 2020 Application/Protocol Name Full Description 01net.com 01net website, a French high-tech news site. 050 plus is a Japanese embedded smartphone application dedicated to 050 plus audio-conferencing. 0zz0.com 0zz0 is an online solution to store, send and share files 10050.net China Railcom group web portal. This protocol plug-in classifies the http traffic to the host 10086.cn. It also 10086.cn classifies the ssl traffic to the Common Name 10086.cn. 104.com Web site dedicated to job research. 1111.com.tw Website dedicated to job research in Taiwan. 114la.com Chinese web portal operated by YLMF Computer Technology Co. Chinese cloud storing system of the 115 website. It is operated by YLMF 115.com Computer Technology Co. 118114.cn Chinese booking and reservation portal. 11st.co.kr Korean shopping website 11st. It is operated by SK Planet Co. 1337x.org Bittorrent tracker search engine 139mail 139mail is a chinese webmail powered by China Mobile. 15min.lt Lithuanian news portal Chinese web portal 163. It is operated by NetEase, a company which 163.com pioneered the development of Internet in China. 17173.com Website distributing Chinese games. 17u.com Chinese online travel booking website. 20 minutes is a free, daily newspaper available in France, Spain and 20minutes Switzerland. This plugin classifies websites. 24h.com.vn Vietnamese news portal 24ora.com Aruban news portal 24sata.hr Croatian news portal 24SevenOffice 24SevenOffice is a web-based Enterprise resource planning (ERP) systems. 24ur.com Slovenian news portal 2ch.net Japanese adult videos web site 2Shared 2shared is an online space for sharing and storage. -

Jan-Mar 2002 High Bandwidth

I N T H I S I S S U E So You Want It In HD One on One makes the transition to 24P HD Peak Experience HD is up to the challenge with this indie feature N A T P E 2 0 0 2 The Mavericks of Multi-Camera 24P Production “The familiar look and feel of HDW-F900 HDCAM 24P CineAlta™ High Definition camcorder. The digital movie camera.* motion picture film are here.” — GEORGE LUCAS If you want to see a movie pro get future,” says Chuck Barbee, the We shot Star Wars: Episode II excited, ask George Lucas, Chuck director of photography. “The in 61 days in 5 countries in the Barbee, or Mike Figgis about Sony whole process was surprisingly Digital Electronic Cinematography. good. And compared to film, raw rain and desert heat averaging Each is using Sony tools to explore tape stock costs next to noth- new creative possibilities. 36 setups per day without a ing. This really lowers the cost “Star Wars: Episode II is our last giant of getting it in the can, which single camera problem. We have DVW-790WS Digital Betacam® camcorder. step toward Digital Cinema,” says means that more projects The gold standard found the picture quality of the in Widescreen George Lucas, describing his decision can get made.” Standard Definition. to shoot principal photography 24P Digital HD system to be with Panavision-modified Sony Mike Figgis challenges our most indistinguishable from film. HDCAM® 24P camcorders. “The basic conventions of narrative in familiar look and feel of motion Timecode, the movie that follows – George Lucas and picture film are present in this four simultaneous storylines in Rick McCallum digital 24P system. -

Transaction Code Description

Transaction Code Description Price KIT ACCESSORY BOOT/ANCHOR 0.00 AMPUTATIONS-SUPPL 0.00 PRESSURE MONITOR SWAN KIT 0.00 LVAD DRIVE LINE KIT 0.00 OXYGEN 0.00 NU-GAUZE,IODAFRM 1INCH 0.00 ARTHROTMY-SUPPL 0.00 BONE & OTHER-SUPPL 0.00 DRUG TEST-DEFINITIVE 1-7 0.00 RESTRAINTS,WRST-LMB 0.00 FEM-POPLIT.BYP-SUPPL 0.00 SORENSON MONITOR KIT 0.00 SUPPLEMENTAL NURSING SYS 0.00 BONE ACCESS KIT 0.00 PERFUSION CUSTOM PACK 0.00 PICC DRESSING CHANGE KIT 0.00 FOLLOLWUP 30 0.00 KIT PORTICO DELIVERY SYST 0.00 PACK,NASAL POST W/DRAWSTR 0.00 PLASTIC RECONS-SUPPL 0.00 COOL CATH TUBING KIT 0.00 CARDIAC ANESTHESIA SUPPLY 0.00 PORT-A-CATH-SUPPL 0.00 CARDINAL PAIN INJ KIT 0.00 BIOPSY TRAY 0.00 KIT(LF)ENDOSCOPIC VASVIEW 0.00 MRI CHEST W/CONTRAST 0.00 PCK CARDIAC HEART STERILE 0.00 POWER PULSE KIT 0.00 LEFT HEART CUSTOM KIT 0.00 M & T-SUPPL 0.00 HIP NAILING-SUPPL 0.00 PULSE LAVAGE KIT 0.00 GASTROSTOMY KIT 0.00 LEEP KIT 0.00 DRUG TEST-DEFINITIVE 8-14 0.00 BOTTLE WATER 1.5L 0.00 TEMP WIRE W/INTRODUCERKIT 0.00 SUPPORTER,A3 ADULT-M 0.00 I & D'S-SUPPL 0.00 CRANIOTOMY-SUPPL 0.00 POUCH FLEX MAXI UROSTOMY 0.00 GOOD GRIP SPOON 0.00 OXYHOOD 12- 0.00 SPINAL CARE KIT JACKSON 0.00 BI&UNILAT VEIN-SUPPL 0.00 DRUG TEST-DEFINITIVE15-21 0.00 CUDDLECUP INSERT 0.00 BLANKET (LF) BAIR HUGGER UPPER BODY 0.00 MASTECTOMY-SUPPL 0.00 LOA RMU 0.00 PACK LINQ 0.00 CHOLECYSTECTOM-SUPPL 0.00 RES BWL,SIG,AP-SUPPL 0.00 TRAY BIOPSY GENERAL UTIL 0.00 KIT(LF)CUSTOM SYRINGE ANGIO 0.00 OXISENSOR(LF)PEDI (PINK) 0.00 THORACIC SURG-SUPPL 0.00 NU-GAUZE PLAIN 1/2INCH 0.00 NU-GAUZE,IODAFRM 1/4INCH 0.00 PICC -

Acme Brick Company: 125 Years Across Three Centuries Is One of His Latest

ACME BRICK COMPANY 125 YEARS ACROSS THREE CENTURIES ACME BRICK COMPANY ACME BRICK COMPANY 125 YEARS ACROSS THREE CENTURIES by Bill Beck Copyright © 2016 by the Acme Brick Company 3024 Acme Brick Plaza Fort Worth, TX 76109 All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this work in any form whatsoever without permission in writing from the publisher, except for brief passages in connection with a review. For information, please write: The Donning Company Publishers 184 Business Park Drive, Suite 206 Virginia Beach, VA 23462 Lex Cavanah, General Manager Nathan Stufflebean, Production Supervisor Richard A. Horwege, Senior Editor Chad Harper Casey, Graphic Designer Monika Ebertz, Imaging Artist Kathy Snowden Railey, Project Research Coordinator Katie Gardner, Marketing and Production Coordinator James H. Railey, Project Director Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Beck, Bill, author. Title: Acme Brick Company : 125 years across three centuries / by Bill Beck. Description: Virginia Beach, VA : The Donning Company Publishers, [2016] | Includes index. Identifiers: LCCN 2016017757 | ISBN 9781681840390 (hard cover : alkaline paper) Subjects: LCSH: Acme Brick Company—History. | Acme Brick Company—Anniversaries, etc. | Brick trade—Texas—Fort Worth—History. | Brickworks—Texas—Fort Worth—History. | Acme Brick Company—Biography. | Fort Worth (Tex.)—Economic conditions. Classification: LCC HD9605.U64 A363 2016 | DDC 338.7/624183609764—dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016017757 Printed in the United States -

IGDA Online Games White Paper Full Version

IGDA Online Games White Paper Full Version Presented at the Game Developers Conference 2002 Created by the IGDA Online Games Committee Alex Jarett, President, Broadband Entertainment Group, Chairman Jon Estanislao, Manager, Media & Entertainment Strategy, Accenture, Vice-Chairman FOREWORD With the rising use of the Internet, the commercial success of certain massively multiplayer games (e.g., Asheron’s Call, EverQuest, and Ultima Online), the ubiquitous availability of parlor and arcade games on “free” game sites, the widespread use of matching services for multiplayer games, and the constant positioning by the console makers for future online play, it is apparent that online games are here to stay and there is a long term opportunity for the industry. What is not so obvious is how the independent developer can take advantage of this opportunity. For the two years prior to starting this project, I had the opportunity to host several roundtables at the GDC discussing the opportunities and future of online games. While the excitement was there, it was hard not to notice an obvious trend. It seemed like four out of five independent developers I met were working on the next great “massively multiplayer” game that they hoped to sell to some lucky publisher. I couldn’t help but see the problem with this trend. I knew from talking with folks that these games cost a LOT of money to make, and the reality is that only a few publishers and developers will work on these projects. So where was the opportunity for the rest of the developers? As I spoke to people at the roundtables, it became apparent that there was a void of baseline information in this segment. -

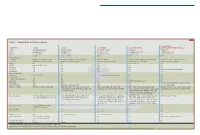

Table 1. Visualization Software Features

Table 1. Visualization Software Features INFORMATIX COMPANY ALIAS ALIAS AUTODESK AUTO•DES•SYS SOFTWARE INTERNATIONAL Product ALIAS IMAGESTUDIO STUDIOTOOLS 11 AUTODESK VIZ 2005 FORM.Z 4.5 PIRANESI 3 E-mail [email protected] [email protected] Use website form [email protected] [email protected] Web site www.alias.com www.alias.com www.autodesk.com www.formz.com www.informatix.co.uk Price $3,999 Starts at $7,500 $1,995 $1,495 $750 Operating systems Supported Windows XP/2000 Professional Windows XP/2000 Professional, SGI IRIX Windows 2000/XP Windows 98/NT/XP/ME/2000, Macintosh 9/X Windows 98 and later, Macintosh OS X Reviewed Windows XP Professional SP1 Windows XP Professional SP1 Windows XP Professional SP1 Windows XP Professional SP1 Windows XP Professional SP1 Modeling None Yes Yes Solid and Surface N/A NURBS Imports NURBS models Yes Yes Yes N/A Refraction Yes Yes Yes Yes N/A Reflection Yes Yes Yes Yes By painting with a generated texture Anti-aliasing Yes Yes Yes Yes N/A Rendering methods Radiosity Yes, Final Gather No Yes, and global illumination/caustics Yes N/A* Ray-tracing Yes Yes Yes Yes N/A* Shade/render (Gouraud) Yes Yes Yes Yes N/A* Animations No† Yes Yes Walkthrough, Quicktime VR N/A Panoramas Yes Yes Yes Yes Can paint cubic panorams and create .MOV files Base file formats AIS Alias StudioTools .wire format MAX FMZ EPX, EPP (panoramas) Import file formats StudioTools (.WIRE), IGES, Maya IGES, STEP, DXF, PTC Granite, CATIA V4/V5, 3DS, AI, XML, DEM, DWG, DXF, .FBX, 3DGF, 3DMF, 3DS, Art*lantis, BMP, DWG EPX, EPP§; Vedute: converts DXF, 3DS; for plans UGS, VDAFS, VDAIS, JAMA-IS, DES, OBJ, EPS IGES, LS, .STL, VWRL, Inventor (installed) DXF, EPS, FACT, HPGL, IGES, AI, JPEG, Light- and elevations; JPG, PNG, TIF, raster formats AI, Inventor, ASCII Scape, Lightwave, TIF, MetaFo;e. -

Millisecond Suppression of Counter-Propagating Optical Signal Using Ultrafast Laser Filaments P

Millisecond Suppression of Counter-propagating Optical Signal using Ultrafast Laser Filaments P. J. Skrodzki1,2, L. A. Finney1,2, M. Burger1,2, J. Nees2, I. Jovanovic1,2 1Nuclear Engineering & Radiological Sciences, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor 48109 United States 2Gérard Mourou Center for Ultrafast Optical Science, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor 48109 United States PI: I. Jovanovic, [email protected] Consortium for Monitoring, Technology, and Verification (MTV) Introduction and Motivation Technical Approach MTV Impact Filaments can be shaped to form dynamic Optical fiber principle structures analogous to optical fibers Nanosecond plasma guiding Skrodzki et al., Phys. Plasmas (2019) Wen et al., J. Phys. D (2012) Microsecond acoustic Millisecond thermal guiding Burger et al., Haz. (shockwave) guiding Uranium exhibits complex spectrum with complicated Mat. (2020 submitted) Rodriguez et al., temporal behavior, and strong early continuum Phys. Rev. E (2004) Conclusion Lahav et al., Phys. Rev. A (2014) Jhajj et al., Phys. Rev. X (2014) Valenzuela et al., App. Phys. B (2014) Results Filamentation solves the problem of extended beam delivery, but how can we overcome challenges in distant signal collection? By imaging the exit plane of the filament, we can reproducibly suppress the counterpropagating probe light Mission Relevance Finney et al., Opt. Letters (2019) Next Steps Modeling & Beam structuring to simulation enable waveguiding of This suppression is long-lived (millisecond scale) optical signals Kemp, Sci. Glob. Sec. (2008) and probably enabled by thermal relaxation of air Expected Impact Remote, rapid detection of nonproliferation- relevant materials using optical spectroscopy We demonstrate strong suppression of on-axis signal without beam shaping which can be used to facilitate background rejection This work was funded in-part by the Consortium for Monitoring, Technology, and Verification under Department of Energy National Nuclear Security Administration award number DE-NA0003920. -

JP-Cumm-2019-Mograph

484 West 43rd Street Apt. 28N New York NY 10036 P: (917) 969-9518 w: https://edgedeepmedia.net w: https://www.behance.net/edgedeep e: [email protected] JEAN-PAUL CUMMINGS BROADCAST DESIGN Creative results oriented, highly skilled professional with a superior combination of artistic and technical expertise. Proven success in visual effects design and a passion for excellence. Able to work independently and thrives in a team and deadline-oriented environment. Skills: 2D Animation, Motion Design, Storyboards, Illustration, Concept Design. Software Skills: Adobe After Effects, Maxon Cinema 4D, Adobe Photoshop, Adobe Illustrator, Adobe Premiere, Apple Final Cut Pro X, Toon Boom Harmony. PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE EDGEDEEP MEDIA 2015 - Current DIRECTOR | PRODUCER | VFX DESIGNER • Created and managed original pitches, concept designs and intellectual properties for media clients. • Produced and directed :30 second commercials for web based multimedia channels. Clients include: White Whale Games, Hudson River Park. iHEARTMEDIA April 2018 2D/3D MOTION GRAPHICS ARTIST • Modeled, textured, set up and animated camera projections in Cinema 4D and After Effects. HORIZON BLUE CROSS/BLUE SHIELD OF NEW JERSEY October 2017 - February 2018 2D/3D MOTION GRAPHICS CONSULTANT • Designed, animated and edited 2D motion elements for internal display. AKA September 2017 - October 2017 2D/3D MOTION GRAPHICS ARTIST • Designed and animated 2D elements, keyed green screen foreground footage and composited background elements for broadcast display kiosks of various broadway productions. EPIX September 2016 - July 2017 2D/3D MOTION GRAPHICS ARTIST • Designed and animated 2D motion elements for broadcast promos including “Tom Popa: Human Mule,” “Berlin Station,” “Get Shorty,” “Graves” and “Epix Hits.” • Created lower 3rds, Next-On graphics and Line-Up graphics for “Epix Drive-In” programming. -

Black Politics in the Age of Jim Crow Memphis, Tennessee, 1865 to 1954

Black Politics in the Age of Jim Crow Memphis, Tennessee, 1865 to 1954 Elizabeth Gritter A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History. Chapel Hill 2010 Approved by: Jacquelyn Dowd Hall W. Fitzhugh Brundage William R. Ferris Genna Rae McNeil Larry J. Griffin Copyright 2010 Elizabeth Gritter ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii Abstract ELIZABETH GRITTER: Black Politics in the Age of Jim Crow: Memphis, Tennessee, 1865 to 1954 (Under the direction of Jacquelyn Dowd Hall) Because the vast majority of black southerners were disenfranchised, most historians have ignored those who engaged in formal political activities from the late nineteenth century through the 1950s. This study is the first to focus on their efforts during this time. In contrast to narratives of the Jim Crow era that portray southern blacks as having little influence on electoral and party politics, this dissertation reveals that they had a significant impact. Using Memphis as a case study, it explores how black men and women maneuvered for political access and negotiated with white elites, especially with machine boss Edward H. Crump. It focuses in particular on Robert R. Church, Jr., who interacted with Crump, mobilized black Memphians, and emerged as the country’s most prominent black Republican in the 1920s. Church and other black Republicans carved out a space for themselves in party politics and opened up doors for blacks in the process. This study argues that formal black political mobilization constituted a major prong of the black freedom struggle during the Jim Crow era in the South. -

H Ica Thera Ractic

ORTHOPAEDIC THE MAGAZINE OF THE �h��ica� Thera�� ORTHOPAEDIC�ractic� SECTION, APTA VOL. 25, NO. 2 2013 ORTHOPAEDIC VOL. 25, NO. 2 2013 �h��ica�In this issue Thera�� �ractic�Regular features 64 A Life of Service: APTA Board Member & Orthopaedic Section Member, 65 Final President’s Message Dave Pariser, PT, PhD APTA President, Paul A. Rockar Jr, PT, DPT, MS 67 President’s Corner: So Who Is This New President? 70 Paris Distinguished Service Award Lecture: Opportunity from Importunity Michael T. Cibulka, PT, DPT, MHS, OCS, FAPTA 68 Editor’s Note: A Good Problem to Have 73 Pathological Cause of Low Back Pain in a Patient Seen Through Direct Access in 104 Book Reviews a Physical Therapy Clinic: A Case Report Margaret M. Gebhardt 106 CSM Award Winners 78 Intramuscular Manual Therapy After Failed Conservative Care: A Case Report 109 CSM Meeting Minutes Brent A. Harper 119 Occupational Health SIG Newsletter 87 Supine Cervical Traction After Anterior Cervical Diskectomy and Fusion: A Case Series 124 Pain SIG Newsletter Jeremy J. McVay 128 Imaging SIG Newsletter 91 Relationship Between Plantar Flexor Weakness and Low Back Region Pain in People with Postpolio Syndrome: A Case Control Study 130 Animal Rehabilitation SIG Newsletter Carolyn Kelley 134 Index to Advertisers 97 Alteration in Corticospinal Excitability, Talocrural Joint Range of Motion, and Lower Extremity Function Following Manipulation in Non-disabled Individuals Todd E. Davenport, Stephen F. Reischl, Somporn Sungkarat, Jason Cozby, Lisa Meyer, Beth E. Fisher OPTP Mission Publication Staff Managing Editor & Advertising Advisory Council To serve as an advocate and resource for Sharon L. -

Shockwave.Com Introduces New Premium Online Gaming Service - Club Shockwave

Shockwave.com Introduces New Premium Online Gaming Service - Club Shockwave New Service Provides Exclusive Access to Hundreds of Online Games, Puzzles and Cash Prizes SAN FRANCISCO, March 24 -- Shockwave.com, a unit of the Nickelodeon Kids and Family Games Group, today launches Club Shockwave -- an all-new premium online gaming service for adults. The new subscription-based service will offer members access to hundreds of exclusive skill games and puzzles and the chance to win cash prizes and to accumulate rewards for time spent online. Club Shockwave is available to the public beginning today for as little as $29.95 per year -- less than $2.50 per month. "There has been explosive growth in online casual gaming in the past couple of years and people want to connect and be rewarded for the time they spend playing games," said Dave Williams, Senior Vice President and General Manager, Nickelodeon Kids and Family Games Group. "Club Shockwave provides extremely high production value games as well as real- world and virtual prizes, and allows users to share their experiences with friends, family and other casual game enthusiasts." Club Shockwave members have unfettered access to online (browser-based) games of skill in a full range of categories including: classic board games, as well as puzzle, word, and strategy games. The service initially launches with 12 exclusive skill games and hundreds of exclusive puzzles. Users have the chance to win daily cash prizes up to $4,999, and one could win an annual grand prize of $25,000*. Additionally, the site offers extensive community features, and other rewards -- including tokens and trophies. -

Blood, Guns, and Plenty of Explosions: the Evolution of American Television Violence

Blood, Guns, and Plenty of Explosions: The Evolution of American Television Violence By Hubert Ta Professor Allison Perlman, Ph.D Departments of Film & Media Studies and History Professor Jayne Lewis, Ph.D Department of English A Thesis Submitted In Partial Completion of the Certification Requirements for The Honors Program of the School of Humanities and The Campuswide Honors Program University of California, Irvine 26 May 2017 ii Table of Contents ACKNOWLEDGMENTS III ABSTRACT IV INTRODUCTION 1 I. BONANZA, THE TV WESTERN, AND THE LEGITIMACY OF VIOLENCE 16 II. THE INTERVENING YEARS: 1960S – 1980S 30 III. COUNTERING THE ACTION EXTRAVAGANZA WITH NUCLEAR FIRE IN THE DAY AFTER 36 IV. THE INTERVENING YEARS: 1990S – 2010S 48 V. THE WALKING DEAD: PUSHING THE ENVELOPE 57 LOOKING AHEAD: VIEWER DISCRETION IS ADVISED 77 WORKS CITED 81 iii Acknowledgments First and foremost, I would like to thank Professor Allison Perlman for her incredible amount of help and guidance as my faculty advisor for this research project. Without her, I would not have been able to get this thesis off the ground and her constant supervision led me to many important texts and concepts that I used for my research. Our discussions, her recommendations and critiques, and her endless ability to be available and help me define my research path has made this research project possible. Thank you so much Professor Perlman! I would also like to thank Professor Jayne Lewis for her guidance as Director of the Humanities Honors Program for 2015 – 2017. She has been extremely supportive throughout my research project with her helpful reminders, her advice and critique of my papers, and her cheerful demeanor which has always made the process more optimistic and fun.