Back and Forth Commuting for Work in Israel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Arrested Development: the Long Term Impact of Israel's Separation Barrier in the West Bank

B’TSELEM - The Israeli Information Center for ARRESTED DEVELOPMENT Human Rights in the Occupied Territories 8 Hata’asiya St., Talpiot P.O. Box 53132 Jerusalem 91531 The Long Term Impact of Israel's Separation Tel. (972) 2-6735599 | Fax (972) 2-6749111 Barrier in the West Bank www.btselem.org | [email protected] October 2012 Arrested Development: The Long Term Impact of Israel's Separation Barrier in the West Bank October 2012 Research and writing Eyal Hareuveni Editing Yael Stein Data coordination 'Abd al-Karim Sa'adi, Iyad Hadad, Atef Abu a-Rub, Salma a-Deb’i, ‘Amer ‘Aruri & Kareem Jubran Translation Deb Reich Processing geographical data Shai Efrati Cover Abandoned buildings near the barrier in the town of Bir Nabala, 24 September 2012. Photo Anne Paq, activestills.org B’Tselem would like to thank Jann Böddeling for his help in gathering material and analyzing the economic impact of the Separation Barrier; Nir Shalev and Alon Cohen- Lifshitz from Bimkom; Stefan Ziegler and Nicole Harari from UNRWA; and B’Tselem Reports Committee member Prof. Oren Yiftachel. ISBN 978-965-7613-00-9 Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................ 5 Part I The Barrier – A Temporary Security Measure? ................. 7 Part II Data ....................................................................... 13 Maps and Photographs ............................................................... 17 Part III The “Seam Zone” and the Permit Regime ..................... 25 Part IV Case Studies ............................................................ 43 Part V Violations of Palestinians’ Human Rights due to the Separation Barrier ..................................................... 63 Conclusions................................................................................ 69 Appendix A List of settlements, unauthorized outposts and industrial parks on the “Israeli” side of the Separation Barrier .................. 71 Appendix B Response from Israel's Ministry of Justice ....................... -

Reducing Revisions in Israel's House Price Index with Nowcasting Models

Ottawa Group, Rio de Janeiro, 2019 16th Meeting of the Ottawa Group International Working Group on Price Indices Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 8-10 May 2019 Reducing Revisions in Israel’s House Price Index with Nowcasting Models1 Doron Sayaga,b, Dano Ben-hura and Danny Pfeffermanna,c,d a b Central Bureau of Statistics, Israel Bar-Ilan University, Israel c d Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Israel University of Southampton, UK Abstract National Statistical Offices must balance between the timeliness and the accuracy of the indicators they publish. Due to late-reported transactions of sold houses, many countries, including Israel, publish a provisional House Price Index (HPI), which is subject to revisions as further transactions are recorded. Until 2018, the Israel Central Bureau of Statistics (ICBS) published provisional HPIs based solely on the known reported transactions, which suffered from large revisions. In this paper we propose a novel method for minimizing the size of the revisions. Noting that the late-reported transactions behave differently from the on-time reported transactions, three types of variables are predicted monthly at the sub-district level as input data for a nowcasting model: (1) the average characteristics of the late-reported transactions; (2) the average price of the late-reported transactions; and (3) the number of late-reported transactions. These three types of variables are predicted separately, based on models fitted to data from previous months. Evaluation of our model shows a reduction in the magnitude of the revisions by more than 50%. The model is now used by the ICBS for the official publication of the provisional HPIs at both the national and district levels. -

S41591-020-0857-9.Pdf

correspondence of video consultation (Fig. 1). The board during the day. The video-consultation distancing while preserving the provision of directors prioritized overcoming the pathway was tested with earlier-appointed of healthcare. limitations hindering the scaling up of video super users in the surgical department Because we believe that video consultation. The success of this process who already knew how to operate the consultation holds promise in optimizing required the immediate cooperation and video-consultation software and hardware. outpatient care in the current crisis, we feel dedication of all stakeholders together, Because the first test failed, another test was that others may benefit from our approach which are otherwise known to be important scheduled for the next morning. and efforts. By sharing this roadmap, we aim barriers to the scaling up of any innovation Day 3, the day on which everything to inspire other centers to scale up virtual within a hospital4. needed to come together, started care to cope with COVID-19. ❐ On day 1, a crisis policy team was with a stand-up meeting and a short appointed, consisting of members of the brainstorming session regarding the failed Esther Z. Barsom , Tim M. Feenstra , department heads of the intensive care test of the day before. By the end of the Willem A. Bemelman, Jaap H. Bonjer and units, clinical wards, outpatient clinics, morning, the new test was successful, Marlies P. Schijven ✉ representatives of the internet technology and the video-consultation pathway was Department of Surgery, Amsterdam Gastroenterology department, the EHR service center merged with the live environment of the and Metabolism, Amsterdam UMC, University of and chief security officers. -

National Outline Plan NOP 37/H for Natural Gas Treatment Facilities

Lerman Architects and Town Planners, Ltd. 120 Yigal Alon Street, Tel Aviv 67443 Phone: 972-3-695-9093 Fax: 9792-3-696-0299 Ministry of Energy and Water Resources National Outline Plan NOP 37/H For Natural Gas Treatment Facilities Environmental Impact Survey Chapters 3 – 5 – Marine Environment June 2013 Ethos – Architecture, Planning and Environment Ltd. 5 Habanai St., Hod Hasharon 45319, Israel [email protected] Unofficial Translation __________________________________________________________________________________________________ National Outline Plan NOP 37/H – Marine Environment Impact Survey Chapters 3 – 5 1 Summary The National Outline Plan for Natural Gas Treatment Facilities – NOP 37/H – is a detailed national outline plan for planning facilities for treating natural gas from discoveries and transferring it to the transmission system. The plan relates to existing and future discoveries. In accordance with the preparation guidelines, the plan is enabling and flexible, including the possibility of using a variety of natural gas treatment methods, combining a range of mixes for offshore and onshore treatment, in view of the fact that the plan is being promoted as an outline plan to accommodate all future offshore gas discoveries, such that they will be able to supply gas to the transmission system. This policy has been promoted and adopted by the National Board, and is expressed in its decisions. The final decision with regard to the method of developing and treating the gas will be based on the developers' development approach, and in accordance with the decision of the governing institutions by means of the Gas Authority. In the framework of this policy, and in accordance with the decisions of the National Board, the survey relates to a number of sites that differ in character and nature, divided into three parts: 1. -

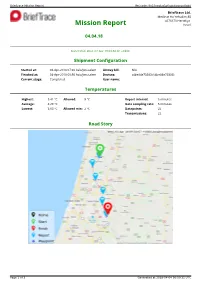

Mission Report Ref.Code: 9N15novkq0w0ggs4ogcwc8g44

Brieftrace Mission Report Ref.code: 9n15novkq0w0ggs4ogcwc8g44 Brieftrace Ltd. Medinat Ha-Yehudim 85 4676670 Herzeliya Mission Report Israel 04.04.18 clalit Status: Success Generated: Wed, 04 Apr 18 09:50:31 +0300 Shipment Configuration Started at: 04-Apr-2018 07:30 Asia/Jerusalem Airway bill: N/A Finished at: 04-Apr-2018 09:50 Asia/Jerusalem Devices: c4be84e73383 (c4be84e73383) Current stage: Completed User name: Shai Temperatures Highest: 5.41 °C Allowed: 8 °C Report interval: 5 minutes Average: 4.29 °C Data sampling rate: 5 minutes Lowest: 3.63 °C Allowed min: 2 °C Datapoints: 22 Transmissions: 22 Road Story Page 1 of 3 Generated at 2018-04-04 06:50:31 UTC Brieftrace Mission Report Ref.code: 9n15novkq0w0ggs4ogcwc8g44 Report Data 13 ° 12 ° 11 ° 10 ° 9 ° Allowed high: 8° C 8 ° C 7 ° ° High e r 6 ° Max: 5.41° C u t a 5 ° r Low e p 4 ° Min: 3.63° C m e 3 ° T Allowed low: 2° C 2 ° 1 ° 0 ° -1 ° -2 ° -3 ° 07:30 07:45 08:00 08:15 08:30 08:45 09:00 09:15 09:30 09:45 Date and time. All times are in Asia/Jerusalem timezone. brieftrace.com Tracker Time Date Temp°CAlert? RH % Location Control Traceability c4be84e73383 07:30 04-04-2018 4.26 79.65 Ha-Matekhet St 17, Kadima Zoran, Israel 636158 dfb902 c4be84e73383 07:36 04-04-2018 4.24 79.75 Ha-Matekhet St 17, Kadima Zoran, Israel 636161 b23bc8 c4be84e73383 07:43 04-04-2018 4.21 79.75 Ha-Matekhet St 17, Kadima Zoran, Israel 636167 c1c01c c4be84e73383 07:49 04-04-2018 4.18 79.85 Ha-Matekhet St 17, Kadima Zoran, Israel 636176 4a3752 c4be84e73383 07:56 04-04-2018 4.21 79.85 Ha-Matekhet St 17, Kadima -

A Tale of Four Cities

A Tale of Four Cities Dr. Shlomo Swirski Academic Director, Adva Center There are many ways of introducing one to a country, especially a country as complex as Israel. The following presentation is an attempt to do so by focusing on 4 Israeli cities (double Charles Dickens's classic book): Tel Aviv Jerusalem Nazareth Beer Sheba This will allow us to introduce some of the major national and ethnic groups in the country, as well as provide a glimpse into some of the major political and economic issues. Tel-Aviv WikiMedia Avidan, Gilad Photo: Tel-Aviv Zionism hails from Europe, mostly from its Eastern countries. Jews had arrived there in the middle ages from Germanic lands – called Ashkenaz in Hebrew. It was the intellectual child of the secular European enlightenment. Tel Aviv was the first city built by Zionists – in 1909 – growing out of the neighboring ancient, Arab port of Jaffa. It soon became the main point of entry into Palestine for Zionist immigrants. Together with neighboring cities, it lies at the center of the largest urban conglomeration in Israel (Gush Dan), with close to 4 million out of 9 million Israelis. The war of 1948 ended with Jaffa bereft of the large majority of its Palestinian population, and in time it was incorporated into Tel Aviv. The day-to-day Israeli- Palestinian confrontations are now distant (in Israeli terms) from Tel Aviv. Tel Aviv represents the glitzi face of Israel. Yet Tel Aviv has two faces: the largely well to do Ashkenazi middle and upper-middle class North, and the largely working class Mizrahi South (with a large concentration of migrant workers). -

Map of Amazya (109) Volume 1, the Northern Sector

MAP OF AMAZYA (109) VOLUME 1, THE NORTHERN SECTOR 1* 2* ISRAEL ANTIQUITIES AUTHORITY ARCHAEOLOGICAL SURVEY OF ISRAEL MAP OF AMAZYA (109) VOLUME 1, THE NORTHERN SECTOR YEHUDA DAGAN 3* Archaeological Survey of Israel Publications of the Israel Antiquities Authority Editor-in-Chief: Zvi Gal Series editor: Lori Lender Volume editor: DaphnaTuval-Marx English editor: Lori Lender English translation: Don Glick Cover: ‘Baqa‘ esh Shamaliya’, where the Judean Shephelah meets the hillcountry (photograph: Yehuda Dagan) Typesetting, layout and production: Margalit Hayosh Preparation of illustrations: Natalia Zak, Elizabeth Belashov Printing: Keterpress Enterprises, Jerusalem Copyright © The Israel Antiquities Authority The Archaeological Survey of Israel Jerusalem, 2006 ISBN 965–406–195–3 www.antiquities.org.il 4* Contents Editors’ Foreword 7* Preface 8* Introduction 9* Index of Site Names 51* Index of Sites Listed by Period 59* List of Illustrations 65* The Sites—the Northern Sector 71* References 265* Maps of Periods and Installations 285* Hebrew Text 1–288 5* 6* Editors’ Foreword The Map of Amazya (Sheet 10–14, Old Israel Grid; sheet 20–19, New Israel Grid), scale 1:20,000, is recorded as Paragraph 109 in Reshumot—Yalqut Ha-Pirsumim No. 1091 (1964). In 1972–1973 a systematic archaeological survey of the map area was conducted by a team headed by Yehuda Dagan, on behalf of the Archaeological Survey of Israel and the Israel Antiquities Authority (formerly the Department of Antiquities and Museums). Compilation of Material A file for each site in the Survey archives includes a detailed report by the survey team members, plans, photographs and a register of the finds kept in the Authority’s stores. -

Israel and the Occupied Territories 2015 Human Rights Report

ISRAEL 2015 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Israel is a multiparty parliamentary democracy. Although it has no constitution, the parliament, the unicameral 120-member Knesset, has enacted a series of “Basic Laws” that enumerate fundamental rights. Certain fundamental laws, orders, and regulations legally depend on the existence of a “state of emergency,” which has been in effect since 1948. Under the Basic Laws, the Knesset has the power to dissolve the government and mandate elections. The nationwide Knesset elections in March, considered free and fair, resulted in a coalition government led by Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu. Civilian authorities maintained effective control over the security services. (An annex to this report covers human rights in the occupied territories. This report deals with human rights in Israel and the Israeli- occupied Golan Heights.) During the year according to Israeli Security Agency (ISA, also known as Shabak) statistics, Palestinians committed 47 terror attacks (including stabbings, assaults, shootings, projectile and rocket attacks, and attacks by improvised explosive devices (IED) within the Green Line that led to the deaths of five Israelis and one Eritrean, and two stabbing terror attacks committed by Jewish Israelis within the Green Line and not including Jerusalem. According to the ISA, Hamas, Hezbollah, and other militant groups fired 22 rockets into Israel and in 11 other incidents either planted IEDs or carried out shooting or projectile attacks into Israel and the Golan Heights. Further -

Geography and Politics: Maps of “Palestine” As a Means to Instill Fundamentally Negative Messages Regarding the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict

Intelligence and Terrorism Information Center at the Center for Special Studies (C.S.S) Special Information Bulletin November 2003 Geography and Politics: Maps of “Palestine” as a means to instill fundamentally negative messages regarding the Israeli-Palestinian conflict The maps of “Palestine” distributed by the Palestinian Authority and other PA elements are an important and tangible method of instilling fundamentally negative messages relating to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. These include ignoring the existence of the State of Israel, and denying the bond between the Jewish people and the Holyland; the obligation to fulfill the Palestinian “right of return”; the continuation of the “armed struggle” for the “liberation” of all of “Palestine”, and perpetuating hatred of the State of Israel. Hence, significant changes in the maps of “Palestine” would be an important indicator of a real willingness by the Palestinians to recognize the right of Israel to exist as a Jewish state and to arrive at a negotiated settlement based on the existence of two states, Israel and Palestine, as envisaged by President George W. Bush in the Road Map. The map features “Palestine” as distinctly Arab-Islamic, an integral part of the Arab world, and situated next to Syria, Egypt and Lebanon. Israel is not mentioned. (Source: “Natioal Education” 2 nd grade textbook, page 16, 2001-2002). Abstract The aim of this document is to sum up the findings regarding maps of “Palestine” (and the Middle East) circulated in the Palestinian areas by the PA and its institutions, and by other organizations (including research institutions, charities, political figures, and terrorist organizations such as Hamas and the Palestinian Islamic Jihad). -

Israel National Report for Habitat III National Israel Report

Israel National Report for Habitat III National Report Israel National | 1 Table of content: Israel National Report for Habitat III Forward 5-6 I. Urban Demographic Issues and Challenges for a New Urban Agenda 7-15 1. Managing rapid urbanization 7 2. Managing rural-urban linkages 8 3. Addressing urban youth needs 9 4. Responding to the needs of the aged 11 5. Integrating gender in urban development 12 6. Challenges Experienced and Lessons Learned 13 II. Land and Urban Planning: Issues and Challenges for a New Urban Agenda 16-22 7. Ensuring sustainable urban planning and design 16 8. Improving urban land management, including addressing urban sprawl 17 9. Enhancing urban and peri-urban food production 18 10. Addressing urban mobility challenges 19 11. Improving technical capacity to plan and manage cities 20 Contributors to this report 12. Challenges Experienced and Lessons Learned 21 • National Focal Point: Nethanel Lapidot, senior division of strategic planing and policy, Ministry III. Environment and Urbanization: Issues and Challenges for a New Urban of Construction and Housing Agenda 23-29 13. Climate status and policy 23 • National Coordinator: Hofit Wienreb Diamant, senior division of strategic planing and policy, Ministry of Construction and Housing 14. Disaster risk reduction 24 • Editor: Dr. Orli Ronen, Porter School for the Environment, Tel Aviv University 15. Minimizing Transportation Congestion 25 • Content Team: Ayelet Kraus, Ira Diamadi, Danya Vaknin, Yael Zilberstein, Ziv Rotem, Adva 16. Air Pollution 27 Livne, Noam Frank, Sagit Porat, Michal Shamay 17. Challenges Experienced and Lessons Learned 28 • Reviewers: Dr. Yodan Rofe, Ben Gurion University; Dr. -

Hamas Attack on Israel Aims to Capitalize on Palestinian

Selected articles concerning Israel, published weekly by Suburban Orthodox Toras Chaim’s (Baltimore) Israel Action Committee Edited by Jerry Appelbaum ( [email protected] ) | Founding editor: Sheldon J. Berman Z”L Issue 8 8 7 Volume 2 1 , Number 1 9 Parshias Bamidbar | 48th Day Omer May 1 5 , 2021 Hamas Attack on Israel Aims to Capitalize on Palestinian Frustration By Dov Lieber and Felicia Schwartz wsj.com May 12, 2021 It is not that the police caused the uptick in violence, forces by Monday evening from Shei kh Jarrah. The but they certainly ran headfirst, full - speed, guns forces were there as part of security measures surrounding blazing into the trap that was set for them. the nightly protests. When the secretive military chief of the Palestinian As the deadline passed, the group sent the barrage of Islamist movement Hamas emerged from the shadows last rockets toward Jerusalem, precipitating the Israeli week, he chose to weigh in on a land dispute in East response. Jerusalem, threatening to retaliate against Israel if Israeli strikes and Hamas rocket fire have k illed 56 Palestinian residents there were evicted from their homes. Palestinians, including 14 children, and seven Israelis, “If the aggression against our people…doesn’ t stop including one child, according to Palestinian and Israeli immediately,” warned the commander, Mohammad Deif, officials. Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu said Israel “the enemy will pay an expensive price.” has killed dozens of Hamas and Palestinian Islamic Jihad Hamas followed through on the threat, firing from the operatives. Gaza Strip, which it governs, over a thousand rockets at Althou gh the Palestinian youth have lacked a single Israel since Monday evening. -

Violations of Civil and Political Rights in the Realm of Planning and Building in Israel and the Occupied Territories

Violations of Civil and Political Rights in the Realm of Planning and Building in Israel and the Occupied Territories Shadow Report Submitted by Bimkom – Planners for Planning Rights Response to the State of Israel’s Report to the United Nations Regarding the Implementation of the Covenant on Civil and Political Rights September 2014 Written by Atty. Sharon Karni-Kohn Edited by Elana Silver and Ma'ayan Turner Contributions by Cesar Yeudkin, Nili Baruch, Sari Kronish, Nir Shalev, Alon Cohen Lifshitz Translated from Hebrew by Jessica Bonn 1 Table of Contents Abstract………………………………………………………………………………3 Introduction……………………………………………………………………….…5 Response to Pars. 44-48 in the State Report: Territorial Application of the Covenant………………………………………………………………………………5 Question 6a: Demolition of Illegal Construstions………………………………...5 Response to Pars. 57-59 in the State Report: House Demolition in the Bedouin Population…………………………………………………………………………....5 Response to Pars. 60-62 in the State Report: House Demolition in East Jerusalem…7 Question 6b: Planning in the Arab Localities…………………………………….8 Response to Pars. 64-77 in the State Report: Outline Plans in Arab Localities in Israel, Infrastructure and Industrial Zones…………………………………………………8 Response to Pars. 78-80 in the State Report: The Eastern Neighborhoods of Jerusalem……………………………………………………………………………10 Question 6c: State of the Unrecognized Bedouin Villages, Means for Halting House Demolitions and Proposed Law for Reaching an Arrangement for Bedouin Localities in the Negev, 2012…………………………………………...15 Response to Pars. 81-88 in the State Report: The Bedouin Population……….…15 Response to Pars. 89-93 in the State Report: Goldberg Commission…………….19 Response to Pars. 94-103 in the State Report: The Bedouin Population in the Negev – Government Decisions 3707 and 3708…………………………………………….19 Response to Par.