Melodic Structure in Bill Evans's 1959 “Autumn Leaves”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guide to Ella Fitzgerald Papers

Guide to Ella Fitzgerald Papers NMAH.AC.0584 Reuben Jackson and Wendy Shay 2015 Archives Center, National Museum of American History P.O. Box 37012 Suite 1100, MRC 601 Washington, D.C. 20013-7012 [email protected] http://americanhistory.si.edu/archives Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 3 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 2 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 3 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 4 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 5 Series 1: Music Manuscripts and Sheet Music, 1919 - 1973................................... 5 Series 2: Photographs, 1939-1990........................................................................ 21 Series 3: Scripts, 1957-1981.................................................................................. 64 Series 4: Correspondence, 1960-1996................................................................. -

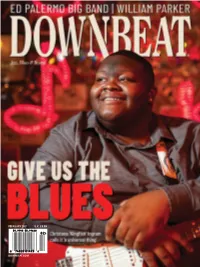

94 DOWNBEAT JUNE 2019 42Nd ANNUAL

94 DOWNBEAT JUNE 2019 42nd ANNUAL JUNE 2019 DOWNBEAT 95 JeJenna McLean, from the University of Northern Colorado in Greeley, is the Graduate College Wininner in the Vocal Jazz Soloist category. She is also the recipient of an Outstanding Arrangement honor. 42nd Student Music Awards WELCOME TO THE 42nd ANNUAL DOWNBEAT STUDENT MUSIC AWARDS The UNT Jazz Singers from the University of North Texas in Denton are a winner in the Graduate College division of the Large Vocal Jazz Ensemble category. WELCOME TO THE FUTURE. WE’RE PROUD after year. (The same is true for certain junior to present the results of the 42nd Annual high schools, high schools and after-school DownBeat Student Music Awards (SMAs). In programs.) Such sustained success cannot be this section of the magazine, you will read the attributed to the work of one visionary pro- 102 | JAZZ INSTRUMENTAL SOLOIST names and see the photos of some of the finest gram director or one great teacher. Ongoing young musicians on the planet. success on this scale results from the collec- 108 | LARGE JAZZ ENSEMBLE Some of these youngsters are on the path tive efforts of faculty members who perpetu- to becoming the jazz stars and/or jazz edu- ally nurture a culture of excellence. 116 | VOCAL JAZZ SOLOIST cators of tomorrow. (New music I’m cur- DownBeat reached out to Dana Landry, rently enjoying includes the 2019 albums by director of jazz studies at the University of 124 | BLUES/POP/ROCK GROUP Norah Jones, Brad Mehldau, Chris Potter and Northern Colorado, to inquire about the keys 132 | JAZZ ARRANGEMENT Kendrick Scott—all former SMA competitors.) to building an atmosphere of excellence. -

June 2020 Volume 87 / Number 6

JUNE 2020 VOLUME 87 / NUMBER 6 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Reviews Editor Dave Cantor Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Design Assistant Will Dutton Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile Vice President of Sales 630-359-9345 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney Vice President of Sales 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Grace Blackford 630-359-9358 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Jeff Johnson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Andy Hermann, Sean J. O’Connell, Chris Walker, Josef Woodard, Scott Yanow; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Andrea Canter; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, Jennifer Odell; New York: Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Philip Freeman, Stephanie Jones, Matthew Kassel, Jimmy Katz, Suzanne Lorge, Phillip Lutz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Bill Milkowski, Allen Morrison, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian; Philadelphia: Shaun Brady; Portland: Robert Ham; San Francisco: Yoshi Kato, Denise Sullivan; Seattle: Paul de Barros; Washington, D.C.: Willard Jenkins, John Murph, Michael Wilderman; Canada: J.D. Considine, James Hale; France: Jean Szlamowicz; Germany: Hyou Vielz; Great Britain: Andrew Jones; Portugal: José Duarte; Romania: Virgil Mihaiu; Russia: Cyril Moshkow. -

The Modality of Miles Davis and John Coltrane14

CURRENT A HEAD ■ 371 MILES DAVIS so what JOHN COLTRANE giant steps JOHN COLTRANE acknowledgement MILES DAVIS e.s.p. THE MODALITY OF MILES DAVIS AND JOHN COLTRANE14 ■ THE SORCERER: MILES DAVIS (1926–1991) We have encountered Miles Davis in earlier chapters, and will again in later ones. No one looms larger in the postwar era, in part because no one had a greater capacity for change. Davis was no chameleon, adapting himself to the latest trends. His innovations, signaling what he called “new directions,” changed the ground rules of jazz at least fi ve times in the years of his greatest impact, 1949–69. ■ In 1949–50, Davis’s “birth of the cool” sessions (see Chapter 12) helped to focus the attentions of a young generation of musicians looking beyond bebop, and launched the cool jazz movement. ■ In 1954, his recording of “Walkin’” acted as an antidote to cool jazz’s increasing deli- cacy and reliance on classical music, and provided an impetus for the development of hard bop. ■ From 1957 to 1960, Davis’s three major collaborations with Gil Evans enlarged the scope of jazz composition, big-band music, and recording projects, projecting a deep, meditative mood that was new in jazz. At twenty-three, Miles Davis had served a rigorous apprenticeship with Charlie Parker and was now (1949) about to launch the cool jazz © HERMAN LEONARD PHOTOGRAPHY LLC/CTS IMAGES.COM movement with his nonet. wwnorton.com/studyspace 371 7455_e14_p370-401.indd 371 11/24/08 3:35:58 PM 372 ■ CHAPTER 14 THE MODALITY OF MILES DAVIS AND JOHN COLTRANE ■ In 1959, Kind of Blue, the culmination of Davis’s experiments with modal improvisation, transformed jazz performance, replacing bebop’s harmonic complexity with a style that favored melody and nuance. -

C-UPPSATS Variationer Av Jazzstandards

2008:059 C-UPPSATS Variationer av jazzstandards Undersökning av hur grundmelodier varieras i jazzinspelningar Daniel Lundström Luleå tekniska universitet C-uppsats Musik Institutionen för Musik och medier Musikhögskolan 2008:059 - ISSN: 1402-1773 - ISRN: LTU-CUPP--08/059--SE Variationer av jazzstandards Undersökning av hur grundmelodier varieras i jazzinspelningar DANIEL LUNDSTRÖM Vetenskaplig handledare: Sverker Jullander Konstnärlig handledare: Claes von Heijne Abstrakt Syftet med den här uppsatsen är att systematiskt inventera olika sätt att förändra en grundmelodi i standardlåtar inom jazzen. Jag har transkriberat inspelningar av jazztrios ledda av pianisterna Bill Evans och McCoy Tyner och analyserat hur de förändrar grundmelodier inom jazzen. Jag har systematiserat melodiska och rytmiska förändringar i kategorier och underubriker. Resultatet av forskningen är tänkt att kunna användas som underlag för konstruktion av undervisningsmaterial. Arbetet innefattar även egna inspelningar. Nyckelord: jazz, standards, piano, jazztrio, Bill Evans, McCoy Tyner. 2 Innehåll 1. Inledning…………………………………………............................................................ 5 Bakgrund…………………………………………...................................................... 5 Syfte………………………………………….............................................................. 5 Material och metod…………………………………………........................................ 5 2. Beskrivning av kompositioner…………………………………………............................. 6 Speak Low…………………………………………................................................... -

The Great Migration and Women in Jazz

BORDER CROSSINGS: THE GREAT MIGRATION AND WOMEN IN JAZZ Dinah Washington – Circa 1952 Birth name Ruth Lee Jones Also known as Queen of the Blues, Queen of the Jukebox, Queen of Jam Sessions Influenced by Mahalia Jackson Origin/Grew Up - Chicago, Illinois, U.S. Genres - Jazz, blues, R&B, gospel, traditional pop music Instruments - Vocals, piano, vibraphone Associated acts - Lionel Hampton, Brook Benton 1924 - Born August 29 - Tuscaloosa, Alabama, U.S. 1939 - Won an amateur contest at Chicago's Regal Theater where she sang "I Can't Face the Music". After winning a talent contest at the age of 15, she began performing in clubs. 1941-42 Performing in such Chicago clubs as Dave's Rhumboogie and the Downbeat Room of the Sherman Hotel (with Fats Waller). She was playing at the Three Deuces, a jazz club, when a friend took her to hear Billie Holiday at the Garrick Stage Bar. Joe Sherman[who?] 1944 - Recording debut for the Keynote label that December with "Evil Gal Blues", written by Leonard Feather and backed by Hampton and musicians from his band, including Joe Morris (trumpet) and Milt Buckner (piano).[1][6][7] Both that record and its follow-up, "Salty Papa Blues", made Billboard's "Harlem Hit Parade". 1946 - Signed with Mercury Records as a solo singer. Her first solo recording for Mercury, a version of Fats Waller's "Ain't Misbehavin'", was another hit, starting a long string of success. 1948 – 1955 27 R&B top ten hits, making her one of the most popular and successful singers of the period. -

JREV3.6FULL.Pdf

KNO ED YOUNG FM98 MONDAY thru FRIDAY 11 am to 3 pm: CHARLES M. WEISENBERG SLEEPY I STEVENSON SUNDAY 8 to 9 pm: EVERYDAY 12 midnite to 2 am: STEIN MONDAY thru SATURDAY 7 to 11 pm: KNOBVT THE CENTER OF 'He THt fM DIAL FM 98 KNOB Los Angeles F as a composite contribution of Dom Cerulli, Jack Tynan and others. What LETTERS actually happened was that Jack Tracy, then editor of Down Beat, decided the magazine needed some humor and cre• ated Out of My Head by George Crater, which he wrote himself. After several issues, he welcomed contributions from the staff, and Don Gold and I began. to contribute regularly. After Jack left, I inherited Crater's column and wrote it, with occasional contributions from Don and Jack Tynan, until I found that the well was running dry. Don and I wrote it some more and then Crater sort of passed from the scene, much like last year's favorite soloist. One other thing: I think Bill Crow will be delighted to learn that the picture of Billie Holiday he so admired on the cover of the Decca Billie Holiday memo• rial album was taken by Tony Scott. Dom Cerulli New York City PRAISE FAMOUS MEN Orville K. "Bud" Jacobson died in West Palm Beach, Florida on April 12, 1960 of a heart attack. He had been there for his heart since 1956. It was Bud who gave Frank Teschemacher his first clarinet lessons, weaning him away from violin. He was directly responsible for the Okeh recording date of Louis' Hot 5. -

(With Chick) for Two Terrific Sides!

RECORDS Chicago. February 15. 1940 Chicago tootin’ not only by the liadet but also by Jerry Jerome, and Johnny Waller Dock (With Chick) Guarmeri’s piano—heard here for the first time on records—comple ments the band well. The rhythm section rocki- along right smartly For Two Terrific Sides! in a good groove. Reverse is i>oor, Ziggj s trumpeting carboning his BY BARRELHOUSE DAN old “Bei Mir” style—a style not conducive to kicks. No vocals. The Because Fats Waller year after Unfortui ntely, however, Mr. Han dy, on the first two, occupies most entire band, except for Noni Ber- year remain« one of the moot pro nardi, is out of i.i n p group. lific of the recording artists, he too of the grooves- -vith pretty sad vo often in overlooked by those who cals. Only Madison’s ten->r breaks Mildred Bailey buy the new jau dist* In almoat through for kicks. The latter coup every weekly batch of RCA-Victor ling finds Mr. Handy blowing a trumpet, and badly. Higginbotham releases, one finds a Waller record Hardly fair samples of Miss ing. Among the current ones are gets ,i a solo on each side but hii tone is frightful. Hall’s clarinet is Bailey’s ability, these sides are “Darktown Strutter's Ball'' and “I noteworthy in that she contrasts Hot di Can't Give You Anything But Love," the only bang. Fans who are senti her new “chamber background” accused c two old evergreens that get royal mental will probably enjoy all of music of piano, drums, trumpet, musical v treatment via the Malic n»-thud these, but for those who are more bass clarinet, two clarys, English are calle and which reveal Eugene Sedric to critical, or must watch their dimes horn, bass and guitai with her be a strk'tlj 18-karal. -

Downbeat.Com February 2021 U.K. £6.99

FEBRUARY 2021 U.K. £6.99 DOWNBEAT.COM FEBRUARY 2021 DOWNBEAT 1 FEBRUARY 2021 VOLUME 88 / NUMBER 2 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Reviews Editor Dave Cantor Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Design Assistant Will Dutton Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile Vice President of Sales 630-359-9345 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney Vice President of Sales 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Grace Blackford 630-359-9358 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Jeff Johnson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Sean J. O’Connell, Chris Walker, Josef Woodard, Scott Yanow; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Andrea Canter; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, Jennifer Odell; New York: Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Philip Freeman, Stephanie Jones, Matthew Kassel, Jimmy Katz, Suzanne Lorge, Phillip Lutz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Bill Milkowski, Allen Morrison, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian; Philadelphia: Shaun Brady; Portland: Robert Ham; San Francisco: Yoshi Kato, Denise Sullivan; Seattle: Paul de Barros; Washington, D.C.: Willard Jenkins, John Murph, Michael Wilderman; Canada: J.D. Considine, James Hale; France: Jean Szlamowicz; Germany: Hyou Vielz; Great Britain: Andrew Jones; Portugal: José Duarte; Romania: Virgil Mihaiu; Russia: Cyril Moshkow. -

DB Music Shop Must Arrive 2 Months Prior to DB Cover Date

05 5 $4.99 DownBeat.com 09281 01493 0 MAY 2010MAY U.K. £3.50 001_COVER.qxd 3/16/10 2:08 PM Page 1 DOWNBEAT MIGUEL ZENÓN // RAMSEY LEWIS & KIRK WHALUM // EVAN PARKER // SUMMER FESTIVAL GUIDE MAY 2010 002-025_FRONT.qxd 3/17/10 10:28 AM Page 2 002-025_FRONT.qxd 3/17/10 10:29 AM Page 3 002-025_FRONT.qxd 3/17/10 10:29 AM Page 4 May 2010 VOLUME 77 – NUMBER 5 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Ed Enright Associate Editor Aaron Cohen Art Director Ara Tirado Production Associate Andy Williams Bookkeeper Margaret Stevens Circulation Manager Kelly Grosser ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Classified Advertising Sales Sue Mahal 630-941-2030 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 Fax: 630-941-3210 www.downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, John McDonough, Howard Mandel Austin: Michael Point; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Robert Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian; New York: Alan Bergman, Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Ira Gitler, Eugene Gologursky, Norm Harris, D.D. -

Stanley Cowell Samuel Blaser Shunzo Ohno Barney

JUNE 2015—ISSUE 158 YOUR FREE GUIDE TO THE NYC JAZZ SCENE NYCJAZZRECORD.COM RAN BLAKE PRIMACY OF THE EAR STANLEY SAMUEL SHUNZO BARNEY COWELL BLASER OHNO WILEN Managing Editor: Laurence Donohue-Greene Editorial Director & Production Manager: Andrey Henkin To Contact: The New York City Jazz Record 116 Pinehurst Avenue, Ste. J41 JUNE 2015—ISSUE 158 New York, NY 10033 United States New York@Night 4 Laurence Donohue-Greene: [email protected] Interview : Stanley Cowell by anders griffen Andrey Henkin: 6 [email protected] General Inquiries: Artist Feature : Samuel Blaser 7 by ken waxman [email protected] Advertising: On The Cover : Ran Blake 8 by suzanne lorge [email protected] Editorial: [email protected] Encore : Shunzo Ohno 10 by russ musto Calendar: [email protected] Lest We Forget : Barney Wilen 10 by clifford allen VOXNews: [email protected] Letters to the Editor: LAbel Spotlight : Summit 11 by ken dryden [email protected] VOXNEWS 11 by katie bull US Subscription rates: 12 issues, $35 International Subscription rates: 12 issues, $45 For subscription assistance, send check, cash or money order to the address above In Memoriam 12 by andrey henkin or email [email protected] Festival Report Staff Writers 13 David R. Adler, Clifford Allen, Fred Bouchard, Stuart Broomer, CD Reviews 14 Katie Bull, Thomas Conrad, Ken Dryden, Donald Elfman, Brad Farberman, Sean Fitzell, Miscellany 41 Kurt Gottschalk, Tom Greenland, Alex Henderson, Marcia Hillman, Event Calendar Terrell Holmes, Robert Iannapollo, 42 Suzanne Lorge, Marc Medwin, Robert Milburn, Russ Musto, Sean J. O’Connell, Joel Roberts, John Sharpe, Elliott Simon, Andrew Vélez, Ken Waxman There is a nobility to turning 80 and a certain mystery to the attendant noun: octogenarian. -

1959 Jazz: a Historical Study and Analysis of Jazz and Its Artists and Recordings in 1959

GELB, GREGG, DMA. 1959 Jazz: A Historical Study and Analysis of Jazz and Its Artists and Recordings in 1959. (2008) Directed by Dr. John Salmon. 69 pp. Towards the end of the 1950s, about halfway through its nearly 100-year history, jazz evolution and innovation increased at a faster pace than ever before. By 1959, it was evident that two major innovative styles and many sub-styles of the major previous styles had recently emerged. Additionally, all earlier practices were in use, making a total of at least ten actively played styles in 1959. It would no longer be possible to denote a jazz era by saying one style dominated, such as it had during the 1930s’ Swing Era. This convergence of styles is fascinating, but, considering that many of the recordings of that year represent some of the best work of many of the most famous jazz artists of all time, it makes 1959 even more significant. There has been a marked decrease in the jazz industry and in stylistic evolution since 1959, which emphasizes 1959’s importance in jazz history. Many jazz listeners, including myself up until recently, have always thought the modal style, from the famous 1959 Miles Davis recording, Kind of Blue, dominated the late 1950s. However, a few of the other great and stylistically diverse recordings from 1959 were John Coltrane’s Giant Steps, Ornette Coleman’s The Shape of Jazz To Come, and Dave Brubeck’s Time Out, which included the very well- known jazz standard Take Five. My research has found many more 1959 recordings of equally unique artistic achievement.