Native American Inspirations Postclassical Ensemble

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Understanding Music Past and Present

Understanding Music Past and Present N. Alan Clark, PhD Thomas Heflin, DMA Jeffrey Kluball, EdD Elizabeth Kramer, PhD Understanding Music Past and Present N. Alan Clark, PhD Thomas Heflin, DMA Jeffrey Kluball, EdD Elizabeth Kramer, PhD Dahlonega, GA Understanding Music: Past and Present is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribu- tion-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. This license allows you to remix, tweak, and build upon this work, even commercially, as long as you credit this original source for the creation and license the new creation under identical terms. If you reuse this content elsewhere, in order to comply with the attribution requirements of the license please attribute the original source to the University System of Georgia. NOTE: The above copyright license which University System of Georgia uses for their original content does not extend to or include content which was accessed and incorpo- rated, and which is licensed under various other CC Licenses, such as ND licenses. Nor does it extend to or include any Special Permissions which were granted to us by the rightsholders for our use of their content. Image Disclaimer: All images and figures in this book are believed to be (after a rea- sonable investigation) either public domain or carry a compatible Creative Commons license. If you are the copyright owner of images in this book and you have not authorized the use of your work under these terms, please contact the University of North Georgia Press at [email protected] to have the content removed. ISBN: 978-1-940771-33-5 Produced by: University System of Georgia Published by: University of North Georgia Press Dahlonega, Georgia Cover Design and Layout Design: Corey Parson For more information, please visit http://ung.edu/university-press Or email [email protected] TABLE OF C ONTENTS MUSIC FUNDAMENTALS 1 N. -

The Society for American Music

The Society for American Music Thirty-Fourth Annual Conference 1 RIDERS IN THE SKY 2008 Honorary Members Riders In The Sky are truly exceptional. By definition, empirical data, and critical acclaim, they stand “hats & shoulders” above the rest of the purveyors of C & W – “Comedy & Western!” For thirty years Riders In The Sky have been keepers of the flame passed on by the Sons of the Pioneers, Gene Autry and Roy Rogers, reviving and revitalizing the genre. And while remaining true to the integrity of Western music, they have themselves become modern-day icons by branding the genre with their own legendary wacky humor and way-out Western wit, and all along encouraging buckaroos and buckarettes to live life “The Cowboy Way!” 2 Society for American Music Thirty-Fourth Annual Conference 3 Society for American Music Thirty-Fourth Annual Conference Hosted by Trinity University 27 February - 2 March 2008 San Antonio, Texas 2 Society for American Music Thirty-Fourth Annual Conference 3 4 Society for American Music Thirty-Fourth Annual Conference 5 Welcome to the 34th annual conference of the Society for American Music! This wonderful meeting is a historic watershed for our Society as we explore the musics of our neighbors to the South. Our honorary member this year is the award-winning group, Riders In The Sky, who will join the San Antonio Symphony for an unusual concert of American music (and comedy). We will undoubtedly have many new members attending this conference. I hope you will welcome them and make them feel “at home.” That’s what SAM is about! Many thanks to Kay Norton and her committee for their exceptional program and to Carl Leafstedt and his committee for their meticulous attention to the many challenges of local arrangements. -

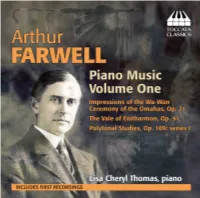

Native American Elements in Piano Repertoire by the Indianist And

NATIVE AMERICAN ELEMENTS IN PIANO REPERTOIRE BY THE INDIANIST AND PRESENT-DAY NATIVE AMERICAN COMPOSERS Lisa Cheryl Thomas, B.M.E., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2010 APPROVED: Adam Wodnicki, Major Professor Steven Friedson, Minor Professor Joseph Banowetz, Committee Member Jesse Eschbach, Chair of the Division of Keyboard Studies Graham Phipps, Director of Graduate Studies in the College of Music James C. Scott, Dean of the College of Music Michael Monticino, Dean of the Robert B. Toulouse School of Graduate Studies Thomas, Lisa Cheryl. Native American Elements in Piano Repertoire by the Indianist and Present-Day Native American Composers. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), May 2010, 78 pp., 25 musical examples, 6 illustrations, references, 66 titles. My paper defines and analyzes the use of Native American elements in classical piano repertoire that has been composed based on Native American tribal melodies, rhythms, and motifs. First, a historical background and survey of scholarly transcriptions of many tribal melodies, in chapter 1, explains the interest generated in American indigenous music by music scholars and composers. Chapter 2 defines and illustrates prominent Native American musical elements. Chapter 3 outlines the timing of seven factors that led to the beginning of a truly American concert idiom, music based on its own indigenous folk material. Chapter 4 analyzes examples of Native American inspired piano repertoire by the “Indianist” composers between 1890-1920 and other composers known primarily as “mainstream” composers. Chapter 5 proves that the interest in Native American elements as compositional material did not die out with the end of the “Indianist” movement around 1920, but has enjoyed a new creative activity in the area called “Classical Native” by current day Native American composers. -

Media – History

Matej Santi, Elias Berner (eds.) Music – Media – History Music and Sound Culture | Volume 44 Matej Santi studied violin and musicology. He obtained his PhD at the University for Music and Performing Arts in Vienna, focusing on central European history and cultural studies. Since 2017, he has been part of the “Telling Sounds Project” as a postdoctoral researcher, investigating the use of music and discourses about music in the media. Elias Berner studied musicology at the University of Vienna and has been resear- cher (pre-doc) for the “Telling Sounds Project” since 2017. For his PhD project, he investigates identity constructions of perpetrators, victims and bystanders through music in films about National Socialism and the Shoah. Matej Santi, Elias Berner (eds.) Music – Media – History Re-Thinking Musicology in an Age of Digital Media The authors acknowledge the financial support by the Open Access Fund of the mdw – University of Music and Performing Arts Vienna for the digital book pu- blication. Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche National- bibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available in the Internet at http:// dnb.d-nb.de This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDeri- vatives 4.0 (BY-NC-ND) which means that the text may be used for non-commercial pur- poses, provided credit is given to the author. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ To create an adaptation, translation, or derivative of the original work and for commercial use, further permission is required and can be obtained by contacting rights@transcript- publishing.com Creative Commons license terms for re-use do not apply to any content (such as graphs, figures, photos, excerpts, etc.) not original to the Open Access publication and further permission may be required from the rights holder. -

Ives: American Visions, American Voices Chapman Orchestra

Chapman University Chapman University Digital Commons Printed Performance Programs (PDF Format) Music Performances 4-2-2016 Ives: American Visions, American Voices Chapman Orchestra Chapman University Wind Symphony Chapman String Quartet Chapman University Singers Chapman Faculty Brass Quintet Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.chapman.edu/music_programs Part of the Music Performance Commons, and the Other Music Commons Recommended Citation Chapman Orchestra, Chapman University Wind Symphony, Chapman String Quartet, Chapman University Singers, and Chapman Faculty Brass Quintet, "Ives: American Visions, American Voices" (2016). Printed Performance Programs (PDF Format). Paper 1557. http://digitalcommons.chapman.edu/music_programs/1557 This Other Concert or Performance is brought to you for free and open access by the Music Performances at Chapman University Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Printed Performance Programs (PDF Format) by an authorized administrator of Chapman University Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CHAPMAN UNIVERSITY College of Performing Arts presents Ives: American Visions, American Voices Presented in conjunction with April 2, 2016 ▪ 4:30 P.M. Musco Center for the Arts Program Variations on America Charles Ives (1874-1954) (orch. William Schuman) Excerpt from Symphony No. 1 in D minor Ives (edited by James B. Sinclair) The Unanswered Question Ives Five Songs Ives (orch. John Adams) I. Thoreau II. Down East III. Cradle Song IV. At the River V. S e r e n i t y Andrew Schmitt, ‘16, baritone The Alcotts from Concord Symphony Ives (orch. Henry Brant) The Chapman Orchestra Daniel Alfred Wachs, music director & conductor ~Changeover~ Program CHAPMAN UNIVERSITY String Quartet No. -

UNIVERSITY of CINCINNATI August 2005 Stephanie Bruning Doctor Of

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date:___________________ I, _________________________________________________________, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: in: It is entitled: This work and its defense approved by: Chair: _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ The Indian Character Piece for Solo Piano (ca. 1890–1920): A Historical Review of Composers and Their Works D.M.A. Document submitted to the College-Conservatory of Music, University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in Piano Performance August 2005 by Stephanie Bruning B.M. Drake University, Des Moines, IA, 1999 M.M. College-Conservatory of Music, University of Cincinnati, 2001 1844 Foxdale Court Crofton, MD 21114 410-721-0272 [email protected] ABSTRACT The Indianist Movement is a title many music historians use to define the surge of compositions related to or based on the music of Native Americans that took place from around 1890 to 1920. Hundreds of compositions written during this time incorporated various aspects of Indian folklore and music into Western art music. This movement resulted from many factors in our nation’s political and social history as well as a quest for a compositional voice that was uniquely American. At the same time, a wave of ethnologists began researching and studying Native Americans in an effort to document their culture. In music, the character piece was a very successful genre for composers to express themselves. It became a natural genre for composers of the Indianist Movement to explore for portraying musical themes and folklore of Native-American tribes. -

Popular Virtuosity: the Role of the Flute and Flutists in Brazilian Choro

POPULAR VIRTUOSITY: THE ROLE OF THE FLUTE AND FLUTISTS IN BRAZILIAN CHORO By RUTH M. “SUNNI” WITMER A THESIS PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2009 1 © 2009 Ruth M. “Sunni” Witmer 2 Para mis abuelos, Manuel y María Margarita García 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS There are very few successes in life that are accomplished without the help of others. Whatever their contribution, I would have never achieved what I have without the kind encouragement, collaboration, and true caring from the following individuals. I would first like to thank my thesis committee, Larry N. Crook, Kristen L. Stoner, and Welson A. Tremura, for their years of steadfast support and guidance. I would also like to thank Martha Ellen Davis and Charles Perrone for their additional contributions to my academic development. I also give muitos obrigados to Carlos Malta, one of Brazil’s finest flute players. What I have learned about becoming a musician, a scholar, and friend, I have learned from all of you. I especially want to thank my family – my parents, Mr. Ellsworth E. and Dora M. Witmer, and my sisters Sheryl, Briana, and Brenda– for it was my parent’s vision of a better life for their children that instilled in them the value of education, which they passed down to us. I am also grateful for the love between all of us that kept us close as a family and rewarded us with the happiness of experiencing life’s joys together. -

Musical Life in Portland in the Early Twentieth Century

MUSICAL LIFE IN PORTLAND IN THE EARLY TWENTIETH CENTURY: A LOOK INTO THE LIVES OF TWO PORTLAND WOMEN MUSICIANS by MICHELE MAI AICHELE A THESIS Presented to the School of Music and Dance and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts June 2011 THESIS APPROVAL PAGE Student: Michele Mai Aichele Title: Musical Life in Portland in the Early Twentieth Century: A Look into the Lives of Two Portland Women Musicians This thesis has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts degree in the School of Music and Dance by: Anne Dhu McLucas Chair Lori Kruckenberg Member Loren Kajikawa Member and Richard Linton Vice President for Research and Graduate Studies/Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded June 2011 ii © 2011 Michele Mai Aichele iii THESIS ABSTRACT Michele Mai Aichele Master of Arts School of Music and Dance June 2011 Title: Musical Life in Portland in the Early Twentieth Century: A Look into the Lives of Two Portland Women Musicians Approved: _______________________________________________ Dr. Anne Dhu McLucas This study looks at the lives of female musicians who lived and worked in Oregon in the early twentieth century in order to answer questions about what musical opportunities were available to them and what musical life may have been like. In this study I am looking at the lives of the composers, performers, and music teachers, Ethel Edick Burtt (1886-1974) and Mary Evelene Calbreath (1895-1972). -

Toccata Classics TOCC 0126 Notes

ARTHUR FARWELL: PIANO MUSIC, VOLUME ONE by Lisa Cheryl Thomas ‘he evil that men do lives ater them’, says Mark Antony in Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar; ‘he good is ot interred with their bones.’ Luckily, that isn’t true of composers: Schubert’s bones had been in the ground for over six decades when the young Arthur Farwell, studying electrical engineering at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, heard the ‘Uninished’ Symphony for the irst time and decided that he was going to be not an engineer but a composer. Farwell, born in St Paul, Minnesota, on 23 March 1872,1 was already an accomplished musician: he had learned the violin as a child and oten performed in a duo with his pianist elder brother Sidney, in public as well as at home; indeed, he supported himself at college by playing in a sextet. His encounter with Schubert proved detrimental to his engineering studies – he had to take remedial classes in the summer to be able to pass his exams and graduated in 1893 – but his musical awareness expanded rapidly, not least through his friendship with an eccentric Boston violin prodigy, Rudolph Rheinwald Gott, and frequent attendance at Boston Symphony Orchestra concerts (as P a ‘standee’: he couldn’t aford a seat). Charles Whiteield Chadwick (1854–1931), one of the most prominent of the New England school of composers, ofered compositional advice, suggesting, too, that Farwell learn to play the piano as soon as possible. Edward MacDowell (1860–1908), perhaps the leading American Romantic composer of the time, looked over his work from time to time – Farwell’s inances forbade regular study with such an eminent igure, but he could aford counterpoint lessons with the organist Homer Albert Norris (1860–1920), who had studied in Paris with Dubois, Gigout and Guilmant, and piano lessons with homas P. -

Representing Classical Music to Children and Young People in the United States: Critical Histories and New Approaches

REPRESENTING CLASSICAL MUSIC TO CHILDREN AND YOUNG PEOPLE IN THE UNITED STATES: CRITICAL HISTORIES AND NEW APPROACHES Sarah Elizabeth Tomlinson A dissertation submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Music in the College of Arts and Sciences. Chapel Hill 2020 Approved by: Chérie Rivers Ndaliko Andrea F. Bohlman Annegret Fauser David Garcia Roe-Min Kok © 2020 Sarah Elizabeth Tomlinson ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Sarah Elizabeth Tomlinson: Representing Classical Music to Children and Young People in the United States: Critical Histories and New Approaches (Under the direction of Chérie Rivers Ndaliko) In this dissertation, I analyze the history and current practice of classical music programming for youth audiences in the United States. My examination of influential historical programs, including NBC radio’s 1928–42 Music Appreciation Hour and CBS television’s 1958–72 Young People’s Concerts, as well as contemporary materials including children’s visual media and North Carolina Symphony Education Concerts from 2017–19, show how dominant representations of classical music curated for children systemically erase women and composers- of-color’s contributions and/or do not contextualize their marginalization. I also intervene in how classical music is represented to children and young people. From 2017 to 2019, I conducted participatory research at the Global Scholars Academy (GSA), a K-8 public charter school in Durham, NC, to generate new curricula and materials fostering critical engagement with classical music and music history. Stemming from the participatory research principle of situating community collaborators as co-producers of knowledge, conducting participatory research with children urged me to prioritize children’s perspectives throughout this project. -

Oscar Levant: Pianist, Gershwinite, Middlebrow Media Star

Washington University in St. Louis Washington University Open Scholarship Arts & Sciences Electronic Theses and Dissertations Arts & Sciences Spring 5-15-2020 Oscar Levant: Pianist, Gershwinite, Middlebrow Media Star Caleb Taylor Boyd Washington University in St. Louis Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/art_sci_etds Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons, Music Commons, and the Sociology Commons Recommended Citation Boyd, Caleb Taylor, "Oscar Levant: Pianist, Gershwinite, Middlebrow Media Star" (2020). Arts & Sciences Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 2169. https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/art_sci_etds/2169 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Arts & Sciences at Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Arts & Sciences Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY IN ST. LOUIS Department of Music Dissertation Examination Committee: Todd Decker, Chair Ben Duane Howard Pollack Alexander Stefaniak Gaylyn Studlar Oscar Levant: Pianist, Gershwinite, Middlebrow Media Star by Caleb T. Boyd A dissertation presented to The Graduate School of Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2020 St. Louis, Missouri © 2020, Caleb T. Boyd Table of Contents List of Figures ................................................................................................................................ -

Leonard Bernstein's the Age of Anxiety

PHILIP GENTRY Leonard Bernstein’s The Age of Anxiety: A Great American Symphony during McCarthyism In 1949, shortly after Harry Truman was sworn into his first full term as president, a group of American writers, artists, scientists, and other public intellectuals organized a “Cultural and Scientific Conference for World Peace,” to be held at the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel in New York City. They were joined by a number of their counterparts in the Soviet Union, or at least as many as could procure a visa from the US State Department. Most prominent among the visitors was composer Dmitri Shostakovich, who through an interpreter delivered a lecture on the dangers of fascist influence in music handcrafted for the occasion by the Soviet govern- ment. The front-page headline in the New York Times the next morning read, “Shostakovich Bids All Artists Lead War on New ‘Fascists.’”1 The Waldorf-Astoria conference was at once the last gasp of the Popu- lar Front, and the beginning of the anticommunist movement soon to be known as McCarthyism. Henry Wallace’s communist-backed third- party bid for the presidency the previous fall had garnered 2.4 percent of the popular vote, but the geopolitical tensions undermining the Popu- lar Front coalition since the Nazi-Soviet Pact of 1939 were out in plain view a decade later. Once-communist intellectuals, like Irving Kristol and Dwight MacDonald, vigorously protested Stalinist influence on the conference, and in an ominous preview of the populist attraction of an- ticommunism, thousands of New Yorkers protested on the streets out- side.