P the Party 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lnt'l Protest Hits Ban on French Left by Joseph Hansen but It Waited Until After the First Round of June 21

THE INSIDE THIS ISSUE Discussion of French election p. 2 MILITANT SMC exclusionists duck •1ssues p. 6 Published in the Interests of the Working People Vol. 32- No. 27 Friday, July 5, 1968 Price JOe MARCH TO FRENCH CONSULATE. New York demonstration against re gathered at Columbus Circle and marched to French Consulate at 72nd Street pression of left in France by de Gaulle government, June 22. Demonstrators and Fifth Ave., and held rally (see page 3). lnt'l protest hits ban on French left By Joseph Hansen but it waited until after the first round of June 21. On Sunday, Dorey and Schroedt BRUSSELS- Pierre Frank, the leader the current election before releasing Pierre were released. Argentin and Frank are of the banned Internationalist Communist Frank and Argentin of the Federation of continuing their hunger strike. Pierre Next week: analysis Party, French Section of the Fourth Inter Revolutionary Students. Frank, who is more than 60 years old, national, was released from jail by de When it was learned that the prisoners has a circulatory condition that required of French election Gaulle's political police on June 24. He had started a hunger strike, the Commit him to call for a doctor." had been held incommunicado since June tee for Freedom and Against Repression, According to the committee, the prisoners 14. When the government failed to file headed by Laurent Schwartz, the well decided to go on a hunger strike as soon The banned organizations are fighting any charges by June 21, Frank and three known mathematician, and such figures as they learned that the police intended to back. -

Move to Win Freedom for the Ft. Jackson 8

The attacks on the Black Panthers - see stories page 8 - Move to win freedom for the Ft. Jackson 8 APRIL 18-Attorneys for the Ft. Jackson Eight have gently needed defense funds- should be sent to the G I moved to obtain a writ of habeas corpus to free the im Civil Liberties Defense Committee, Box 355, Old Chelsea prisoned antiwar Gis. Five of the servicemen have been Station, New York, N.Y. 10010. in the stockade since March 20 and three are under Since the development of the Ft. Jackson Gis United barracks detention. Their sole crime is association with and the Army's attempt to victimize those associated with Gis United Against the War in Vietnam and seeking to it, major national press and television publicity has fo exercise their constitutional right of free speech. cused on the still-growing antiwar servicemen's group. In Jailing of the men and the court-martial threatened addition, there have been increasing protests against the against them violates military law as well as their civil Army's punitive actions. rights. The Uniform Code of Military Justice provides A mass rally of striking students at Harvard voted for pre-trial confinement only in cases where there is unanimously to send a message to the G Is declaring: danger the defendant will not appear for trial. ((We see our fight to abolish ROTC at Harvard and your Attorneys for the eight have called on the Secretary fight within the military as one and the same struggle of the Army to act against the commanding officer re to end the war. -

English Translations) Miners to Get Another Master in in the Labor Movement, Has Given and a Cross Petition Has Been 17 Uprising

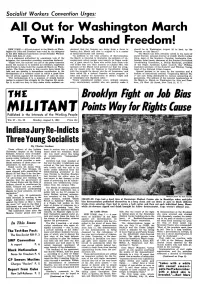

Socialist Workers Convention Urges: All Out for Washington March To Win Jobs and Freedom! NEW YORK — All-out support to the March on Wash derstand that the Negroes are doing them a favor in should be in Washington August 28 to back up the ington for Jobs and Freedom was voted by the delegates leading this March and that to support it is a matter Negroes on this March.” to the 20th National Convention of the Socialist Workers of bread-and-butter self interest. The March has been officially called in the name Of Party held here in July. “In addition to the vital problem of discrimination, James Farmer, national director of CORE; Martin Luther In a statement authorized by unanimous vote of the the March is intended to dramatize the problem of un King, head of the Southern Christian Leadership Con delegates, the convention presiding committee declared: employment which weighs most heavily on Negro work ference; John Lewis, chairman of the Student Nonviolent “Right now, the number one job of the party branches ers. A giant march by those who suffer from these evils Coordinating Committee; A. Phillip Randolph, president across the country is to mobilize all members, supporters w ill strike fear into their enemies on Capitol Hill. The of the Negro American Labor Council; Roy Wilkins, and friends to help build the August 28 March on Wash sponsors of the March have pointed out that the strug executive secretary of the NAACP; and Whitney Young, ington. The Negro people in this country have taken the gle for decent jobs for Negroes is ‘inextricably linked head of the National Urban League. -

Is U.S. Really on the Eve of a Maior Repression? --See Pages

Tens of thousands march in Berkeley -page 4 - AN ANALYSIS: Is U.S. really on the eve of a maior repression? --see pageS \\ T~e streets of out c.oullt. Th . ry are in ~ ·• · e untversities a~ filled w'th 1i ·11lrmo;/, be.llin9 and riofino. G,hl . ' s llclent4 re- ~ ;.;~ rnurusts are t6A des ·i·nroy our countru. "R.• u 55; · . .· ~kin, +o "' th h. ./. .· a IS tnre m . Wt · . er m~t And th · ·· a erun, U.s v d · · ~ teputlk is in d tes, an,g~r from within and 'Niiho it anser. law and order I Yes wi+f ~~· u. We ne~a . • ' ·~ow, awana. o d. our natron cannot- S(Jrv· · r er our .sfo II IVe .. '• Y-Jf: Sha\1 w an r. - A~olf all't bur3, Ge Photo by Angela Vintber AN ECHO? A growing number of U.S. politicians are mouthing labor movement as Hitler did before he began "restoring law phrases similar to the famous quotation from Hitler depicted and order." The scene here is from the University of California here. The problem of the U. S. politicians is that they are bogged at Los Angeles where, May 26, 30 percent of the 32,000-member down in Vietnam and facing mounting militancy of black, brown student body joined a strike in solidarity with embattled Berkeley and other third world people, as well as a spreading youth students. It was an unprecedented action for UCLA which has radicalization. With all these difficulties, and more, they are lagged behind general campus militancy. -

MPS-0742197.Pdf

MPS-0742197 S.C. No (Plain) POLICE SPECIAL BRANCH Special Report 2nd day of October 1968 . •• t) ‘q • • k• os SUBJECT I Au . On Wednesday, 2nd October, 1968, at 10.30 a.m., Press the Vietnam Solidarity Campaign Autumn Offensive Conference. Ad Hoc Committee held a press conference in a small club room at Conway Mall, Red Lion Square, London, W.C.1, which was attended by some 30 representatives Reference to Papers of national newspapers and the Independent Television Authority. Attached is a printed statement handed to all present. The V.S.C. Ad Hoc Committee was represented by the following persons: Fergus NICHOLSON*/ Communist Party Ernie TTE / V.S.C. National Council William Alan HARRIS/ V.S.C. Ad Hoc Committee Tariq ALI ve V.O.C. National Council. Barney DAVIS I Secretary, Young Communist League Henry WORTI._: Stop It Committee Bill TUT.,:_.:3 Independent Labour Party These persons formed a panel to answer questions put by reporters but skilfully evaded the various issues raised and gave little information other than that contained in the official statement. The main additional points of interest are summarised below. u MPS-0742197 MPS-0742197 NO. 2. TATE said that there were plenty of indications that the number of persons involved on 27th October would be greatly in excess of the previous mass demonstrations of October, 1967, and March, 1968, and he considered that it was possible that 70,000 to 100,000 would tak part in the march. Whereas one bus had brought people from Glasgow in March, 1968 at least four would come this time and about ten other buses would bring people from elsewhere in Scotland. -

The Radicalization of the Student Youth Movement in Mexico During the 1960S

Western Washington University Western CEDAR WWU Graduate School Collection WWU Graduate and Undergraduate Scholarship 2012 Re-envisioning society: the radicalization of the student youth movement in Mexico during the 1960s Lily A. (Lily Ann) Fox Western Washington University Follow this and additional works at: https://cedar.wwu.edu/wwuet Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Fox, Lily A. (Lily Ann), "Re-envisioning society: the radicalization of the student youth movement in Mexico during the 1960s" (2012). WWU Graduate School Collection. 219. https://cedar.wwu.edu/wwuet/219 This Masters Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the WWU Graduate and Undergraduate Scholarship at Western CEDAR. It has been accepted for inclusion in WWU Graduate School Collection by an authorized administrator of Western CEDAR. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RE-ENVISIONING SOCIETY: THE RADICALIZATION OF THE STUDENT YOUTH MOVEMENT IN MEXICO DURING THE 1960s By Lily Fox Accepted in Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts Kathleen Kitto, Dean of the Graduate School ADIVSORY COMMITTEE Chair, Dr. A. Ricardo López Dr. Kathleen Kennedy Dr. Kevin Leonard Master’s Thesis In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a master’s degree at Western Washington University, I grant to Western Washington University the non- exclusive royalty-free right to archive, reproduce, distribute, and display the thesis in any and all forms, including electronic format, via any digital library mechanisms maintained by WWU. I represent and warrant this is my original work, and does not infringe or violate any rights of others. -

False Accusation Delays Election

False Accusation Delays Election By JIM DOUGHERTY candidates), referred to Harry Temple, AS3, as "the principal A false charge by one of senator" at an SGA meeting the candidates has resulted in responsible for approving $7 4 a postponement of the for the Prisoner's Solidarity College Councils election Committee of Delaware. until Monday. The charge, part of a OPPOSITION prepared statement published Temple, it was learned, in Tuesday's Review, was not at the meeting in concerned two of the question until after the issue candidates running for had been voted on. This was president of the College in direct opposition to the Councils. charge made earlier by Ajit George, AS4, in that George. statement (which was a A special closed spssion of response to a Review the SGA elections' committPe questionnaire sent to all the was then called Tuesday afternoon to resolve what seemed to be becoming a I . major issue. HUNDREDS of students made the best of a 'hot situation' on Tuesday. while waiting to sign-up Democrats for apartments in the Christiana Towers. See photos and text on page 9. POSTPONEMENT The Democratic At that meeting, the Committee for the 25th nature and the harm of Lhe Representative district (in charge was discussed, and it tatistics Fail to Show Strength Newark), will hold a public was decided to postponE:> the meeting at 8 p.m. Monday at entire' College Councils Downes Elementary School election until Monday. According to Barb Dail, f Delaware Republican arty on Casho Mill Road. The chairwoman of thP Plections' Editor's Note: This is the first Representative Harris B. -

Scrutinizing Federal Electoral Qualifications

Scrutinizing Federal Electoral Qualifications DEREK T. MULLER* Candidates for federal office must meet several constitutional qualifications. Sometimes, whether a candidate meets those qualifications is a matter of dispute. Courts and litigants often assume that a state has the power to include or exclude candidates from the ballot on the basis of the state’s own scrutiny of candidates’ qualifications. Courts and litigants also often assume that the matter is not left to the states but to Congress or another political actor. But those contradictory assumptions have never been examined, until now. This Article compiles the mandates of the Constitution, the precedents of Congress, the practices of states administering the ballot, and judicial precedents. It concludes that states have no role in evaluating the qualifications of congressional candidates—the matter is reserved to the people and to Congress. It then concludes that while states have the power to scrutinize qualifications for presidential candidates, they are not obligated to do so under the Constitution. If state legislatures choose to exercise that power, it comes at the risk of ceding reviewing power to election officials, partisan litigants, and the judiciary. The Article then offers a framework for future litigation that protects the guarantees of the Constitution, the rights of the voters, and the authorities of the sovereigns. INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................... 560 I. CONSTITUTIONAL QUALIFICATIONS -

The Guardian, April 26, 1972

Wright State University CORE Scholar The Guardian Student Newspaper Student Activities 4-26-1972 The Guardian, April 26, 1972 Wright State University Student Body Follow this and additional works at: https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/guardian Part of the Mass Communication Commons Repository Citation Wright State University Student Body (1972). The Guardian, April 26, 1972. : Wright State University. This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Activities at CORE Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Guardian Student Newspaper by an authorized administrator of CORE Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SBP candidates respond to queries of press, organizations representatives BY JAN DAGLEY dantlal candidates Ssre not run Ron Paul, staff writer for the can promote s>.nsn! Interests Managing Editor their campaign* through letters GUARDIAN and presently one c£ ln the beet manner," Paul said, published in the GUARDIAN, two student representatives 011 "Those who hare said the new committee I was In charge of the SBi' governing the senate w# BOWl IJ will be suf sst up a free day care cen- and tb> Sto^te governing the until we can find a bat- Four at the five announced it was decided that Uw cam- the Academic Council, claimed c nslttutlon Is nasty must re- . (( flclent candidates for student bcdjr palgn would be more fair and that he was running solely to member It's taken over a year ire "!*' 2.°° V me" ter. I worked on an entertain- 5 Bp. P**) tried to work for ieT # president met a panel at stu- more "professional" for all bring about the Implication <M now." he ceot&uied, ment series that had $20,000 the stuWKtts en the Academic Students ought to be placed dent press and special Interest concerned If platforms were the proposed new constltiAlon, Ted Low, whose campaign pos- LOT'S platform calls for a day to get rid of at the end of the Council, kg ft* not easy.four- OH the board of trustees. -

Full Thesis Draft No Pics

A whole new world: Global revolution and Australian social movements in the long Sixties Jon Piccini BA Honours (1st Class) A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Queensland in 2013 School of History, Philosophy, Religion & Classics Abstract This thesis explores Australian social movements during the long Sixties through a transnational prism, identifying how the flow of people and ideas across borders was central to the growth and development of diverse campaigns for political change. By making use of a variety of sources—from archives and government reports to newspapers, interviews and memoirs—it identifies a broadening of the radical imagination within movements seeking rights for Indigenous Australians, the lifting of censorship, women’s liberation, the ending of the war in Vietnam and many others. It locates early global influences, such as the Chinese Revolution and increasing consciousness of anti-racist struggles in South Africa and the American South, and the ways in which ideas from these and other overseas sources became central to the practice of Australian social movements. This was a process aided by activists’ travel. Accordingly, this study analyses the diverse motives and experiences of Australian activists who visited revolutionary hotspots from China and Vietnam to Czechoslovakia, Algeria, France and the United States: to protest, to experience or to bring back lessons. While these overseas exploits, breathlessly recounted in articles, interviews and books, were transformative for some, they also exposed the limits of what a transnational politics could achieve in a local setting. Australia also became a destination for the period’s radical activists, provoking equally divisive responses. -

Goerge Lavan Weissman Papers

George Lavan Weissman Collection Papers, 1935-1985 3 linear feet 3 storage boxes Accession #1347 DALNET # OCLC # George Lavan Weissman was born in Chicago in 1916 and grew up in Boston, where he attended Boston Latin School and Harvard College. While at Harvard during the Great Depression, he became a Marxist, joined the Young People’s Socialist League and the Socialist Party and volunteered as an organizer for several labor unions in New England. Weissman followed the Trotskyists out of the SP after their expulsion in 1937 and helped found the Socialist Workers Party and the Fourth International in 1938. He married fellow SWP activist, Constance Fox Harding, in 1943. As a self-described “party functionary,” Weissman was a branch organizer in Boston (1939-41) and Youngstown (1946), director and editor of Pioneer Publishing and Pathfinder Press (1947-81), manager of Mountain Spring Camp (1948-62) and editor and writer for the Militant and other party publications, including the first English-language anthology of Che Guevara’s writings, Che Guevara Speaks and The War Correspondence of Leon Trotsky: The Balkan Wars, 1912-1913 (He had become United States literary representative of the Trotsky estate after Natalia Sedova Trotsky’s death in 1962). After his expulsion from the SWP in the great purge of 1983-1984, Weissman joined with others to form the Fourth Internationalist Tendency and became a member of the Bulletin in Defense of Marxism editorial board. He died on March 28, 1985. The George Lavan Weissman Collection consists of correspondence (both his and Connie Weissman’s), the manuscript for volume two of Trotsky’s war correspondence, on which Weissman was working at the time of his death, and numerous pamphlets and other publications put out by the SWP and a variety of civil rights and civil libertarian organizations to which he belonged. -

Joseph Hansen Papers

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf78700585 No online items Register of the Joseph Hansen papers Finding aid prepared by Joseph Hansen Hoover Institution Archives 434 Galvez Mall Stanford University Stanford, CA, 94305-6003 (650) 723-3563 [email protected] © 1998, 2006, 2012 Register of the Joseph Hansen 92035 1 papers Title: Joseph Hansen papers Date (inclusive): 1887-1980 Collection Number: 92035 Contributing Institution: Hoover Institution Archives Language of Material: English Physical Description: 109 manuscript boxes, 1 oversize box, 3 envelopes, 1 audio cassette(46.2 linear feet) Abstract: Speeches and writings, correspondence, notes, minutes, reports, internal bulletins, resolutions, theses, printed matter, sound recording, and photographs relating to Leon Trotsky, activities of the Socialist Workers Party in the United States, and activities of the Fourth International in Latin America, Western Europe and elsewhere. Physical Location: Hoover Institution Archives Creator: Hansen, Joseph, Access The collection is open for research; materials must be requested at least two business days in advance of intended use. Publication Rights For copyright status, please contact the Hoover Institution Archives. Preferred Citation [Identification of item], Joseph Hansen papers, [Box no., Folder no. or title], Hoover Institution Archives. Acquisition Information Acquired by the Hoover Institution Archives in 1992. Accruals Materials may have been added to the collection since this finding aid was prepared. To determine if this has occurred, find the collection in Stanford University's online catalog at http://searchworks.stanford.edu . Materials have been added to the collection if the number of boxes listed in the online catalog is larger than the number of boxes listed in this finding aid.