Digitizing and Transcribing the Blanchard Brothers’ Civil War Letters

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

89.1963.1 Iron Brigade Commander Wayne County Marker Text Review Report 2/16/2015

89.1963.1 Iron Brigade Commander Wayne County Marker Text Review Report 2/16/2015 Marker Text One-quarter mile south of this marker is the home of General Solomon A. Meredith, Iron Brigade Commander at Gettysburg. Born in North Carolina, Meredith was an Indiana political leader and post-war Surveyor-General of Montana Territory. Report The Bureau placed this marker under review because its file lacked both primary and secondary documentation. IHB researchers were able to locate primary sources to support the claims made by the marker. The following report expands upon the marker points and addresses various omissions, including specifics about Meredith’s political service before and after the war. Solomon Meredith was born in Guilford County, North Carolina on May 29, 1810.1 By 1830, his family had relocated to Center Township, Wayne County, Indiana.2 Meredith soon turned to farming and raising stock; in the 1850s, he purchased property near Cambridge City, which became known as Oakland Farm, where he grew crops and raised award-winning cattle.3 Meredith also embarked on a varied political career. He served as a member of the Wayne County Whig convention in 1839.4 During this period, Meredith became concerned with state internal improvements: in the early 1840s, he supported the development of the Whitewater Canal, which terminated in Cambridge City.5 Voters next chose Meredith as their representative to the Indiana House of Representatives in 1846 and they reelected him to that position in 1847 and 1848.6 From 1849-1853, Meredith served -

Gettysburg: Three Days of Glory Study Guide

GETTYSBURG: THREE DAYS OF GLORY STUDY GUIDE CONFEDERATE AND UNION ORDERS OF BATTLE ABBREVIATIONS MILITARY RANK MG = Major General BG = Brigadier General Col = Colonel Ltc = Lieutenant Colonel Maj = Major Cpt = Captain Lt = Lieutenant Sgt = Sergeant CASUALTY DESIGNATION (w) = wounded (mw) = mortally wounded (k) = killed in action (c) = captured ARMY OF THE POTOMAC MG George G. Meade, Commanding GENERAL STAFF: (Selected Members) Chief of Staff: MG Daniel Butterfield Chief Quartermaster: BG Rufus Ingalls Chief of Artillery: BG Henry J. Hunt Medical Director: Maj Jonathan Letterman Chief of Engineers: BG Gouverneur K. Warren I CORPS MG John F. Reynolds (k) MG Abner Doubleday MG John Newton First Division - BG James S. Wadsworth 1st Brigade - BG Solomon Meredith (w) Col William W. Robinson 2nd Brigade - BG Lysander Cutler Second Division - BG John C. Robinson 1st Brigade - BG Gabriel R. Paul (w), Col Samuel H. Leonard (w), Col Adrian R. Root (w&c), Col Richard Coulter (w), Col Peter Lyle, Col Richard Coulter 2nd Brigade - BG Henry Baxter Third Division - MG Abner Doubleday, BG Thomas A. Rowley Gettysburg: Three Days of Glory Study Guide Page 1 1st Brigade - Col Chapman Biddle, BG Thomas A. Rowley, Col Chapman Biddle 2nd Brigade - Col Roy Stone (w), Col Langhorne Wister (w). Col Edmund L. Dana 3rd Brigade - BG George J. Stannard (w), Col Francis V. Randall Artillery Brigade - Col Charles S. Wainwright II CORPS MG Winfield S. Hancock (w) BG John Gibbon BG William Hays First Division - BG John C. Caldwell 1st Brigade - Col Edward E. Cross (mw), Col H. Boyd McKeen 2nd Brigade - Col Patrick Kelly 3rd Brigade - BG Samuel K. -

Course Reader

Course Reader Gettysburg: History and Memory Professor Allen Guelzo The content of this reader is only for educational use in conjunction with the Gilder Lehrman Institute’s Teacher Seminar Program. Any unauthorized use, such as distributing, copying, modifying, displaying, transmitting, or reprinting, is strictly prohibited. GETTYSBURG in HISTORY and MEMORY DOCUMENTS and PAPERS A.R. Boteler, “Stonewall Jackson In Campaign Of 1862,” Southern Historical Society Papers 40 (September 1915) The Situation James Longstreet, “Lee in Pennsylvania,” in Annals of the War (Philadelphia, 1879) 1863 “Letter from Major-General Henry Heth,” SHSP 4 (September 1877) Lee to Jefferson Davis (June 10, 1863), in O.R., series one, 27 (pt 3) Richard Taylor, Destruction and Reconstruction: Personal Experiences of the Late War (Edinburgh, 1879) John S. Robson, How a One-Legged Rebel Lives: Reminiscences of the Civil War (Durham, NC, 1898) George H. Washburn, A Complete Military History and Record of the 108th Regiment N.Y. Vols., from 1862 to 1894 (Rochester, 1894) Thomas Hyde, Following the Greek Cross, or Memories of the Sixth Army Corps (Boston, 1894) Spencer Glasgow Welch to Cordelia Strother Welch (August 18, 1862), in A Confederate Surgeon’s Letters to His Wife (New York, 1911) The Armies The Road to Richmond: Civil War Memoirs of Major Abner R. Small of the Sixteenth Maine Volunteers, ed. H.A. Small (Berkeley, 1939) Mrs. Arabella M. Willson, Disaster, Struggle, Triumph: The Adventures of 1000 “Boys in Blue,” from August, 1862, until June, 1865 (Albany, 1870) John H. Rhodes, The History of Battery B, First Regiment Rhode Island Light Artillery, in the War to Preserve the Union (Providence, 1894) A Gallant Captain of the Civil War: Being the Record of the Extraordinary Adventures of Frederick Otto Baron von Fritsch, ed. -

Reign of Terror in West Kentucky?

REIGN OF TERROR IN WEST KENTUCKY? By Dieter C. Ullrich and Berry Craig During fifty-one days in the settlers immigrated to the Pur- tary Academy from 1835 to 1839 summer of 1864 a “reign of ter- chase from the South and many and graduated twenty-fourth ror” existed in Western Kentucky still communicated with family in out of a class of thirty-two. After under the military command of that section of the country. The graduation he was commissioned General Eleazar Arthur Paine, at region’s trade routes also pointed as a Second Lieutenant in the 1st least that is what historians and South and its economy relied Regiment of Infantry and sta- folklorists have written over the more heavily upon slavery than tioned at Fort Pleasant in Flori- past 150 years. However, new ev- other regions of Kentucky: the da. Though the Second Seminole General Elea- idence from contemporary doc- number of slaves in the Purchase War was in progress, Paine saw zar Arthur Paine uments provide a contradictory increased by over 40 percent only post duty, serving on the (1815-1882). LOC narrative to the story. Western in the decade prior to the war. staff of General Zachary Taylor. Kentucky, particularly The political landscape reflected On August 24, 1840, he submit- the seven counties these facts, and secessionist and ted his resignation, stating his in the far south- Southern Rights candidates over- father’s health was in decline and west known as whelmingly won seats in both he must return to Ohio to assist the Jackson state and national elections in with the family businesses. -

Gettysburg OOB Source

Gettysburg OOB Source: Gettysburg 1863 by Carl Smith (Copyright, Osprey Publishing Ltd, 1998) North Union Army of the Potomac (MG George G. Meade) 112,735 total, 95,799 engaged General HQ (Provost Marshal M. Patrick) 1528 Guards & Orderlies (Oneida NY Cav.) 42 93rd NY (detachments) 148 8th U.S. 401 2nd PA Cavalry 489 6th PA (cos. E & I) 81 Regular Cav. Det. From 1st, 2nd, 5th, and 6th U.S. 15 Signal Corps 51 Engineers (not present) ? 15th NY ? 50th NY ? U.S. Battalion of Engineers ? I Corps (MG John F. Reynolds) (MG Abner Doubleday) (MG John Newton) 12596 General HQ 1st Maine Cav. (Co. L) 57 B/121st PA 306 1st Division (BG James S. Wadsworth) 3860 1st (Iron) Brigade (BG Solomon Meredith) (Col. W.W. Robinson) 1829 2nd WI 302 6th WI 344 7th WI 364 19th IN 308 24th MI 496 2nd Brigade (BG Lysander Cutler) 2020 84th NY (14th Brooklyn Militia) 318 147th NY 380 76th NY 375 95th NY 241 56th PA 252 7th IN 437 2nd Division (BG John C. Robinson) 3027 1st Brigade (BG Gabriel R. Paul) 1829 94th NY 411 104th NY 309 11th PA 292 107th PA 255 16th ME 298 13th MA 284 2nd Brigade (MG Henry Baxter) 1198 12th MA 261 83rd NY (9th Militia) 215 97th NY 236 88th PA 274 90th PA 208 3rd Division (MG Abner Doubleday) (BG Thomas A. Rowley) 4711 Provost Guard 149th PA (Co. C) 60 1st Brigade (BG T. Rowley) (Col. Chapman Biddle) 1387 80th NY 287 121st PA 263 142nd PA 362 151st PA 467 2nd "Bucktail" Brigade (Col. -

Winter 2019 Edition January 1

Thomas M. Holt Lodge # 492 A.F. & A.M. Regular Meetings 1st and 3rd Thursday of the Month at 7:30pm Address: 512 Johnson Avenue, Graham, NC, 27253 Websites: www.thomasmholt492.org or 492-nc.ourlodgepage.com Upcoming Events The Holler Log – Winter 2019 Edition January 1 Happy New Year - 2019 “May the Year Ahead Bring You Good Messages from the East: Luck, Good Health, Good Fortune, Great Success, and Lots of Brotherly Love.” Brethren, January 3 As the sun rises in the East to open and Dinner @ 6:30 PM govern the day, so shall the sun rise on all of Stated Meeting @ 7:30 PM us, as we kick off the new year !! So Happy New Year, Thomas M. Holt Lodge # 492 !! January 17 First off, I would like to thank the Dinner @ 6:30 PM Stated Meeting @ 7:30 PM Brethren of Thomas M Holt Lodge, thank you for your confidence and trust in me to lead this lodge, by electing me and giving me this opportunity to serve February 7 as your Worshipful Master for the next year. It is indeed a great honor and Dinner @ 6:30 PM privilege to serve you in this capacity and one I will not take for granted. Stated Meeting @ 7:30 PM Second, I would like to thank and congratulate all of our 2019 officers, February 21 and thank them for volunteering their time to serve with me, and accepting Dinner @ 6:30 PM the responsibilities that your individual chair requires. Installation was held Stated Meeting @ 7:30 PM on Sunday, December 16, with Worshipful Brother Alvin Billings presiding and it fills my heart with joy to see some many Masons, their Families, and March 7 Friends in attendance. -

“I Have Never Seen the Like Before”

“I Have Never Seen the Like Before” Herbst Woods, July 1, 1863 D. Scott Hartwig Of the 160 acres that John Herbst farmed during the summer of 1863, 18 were in a woodlot on the northwestern boundary, adjacent to the farm owned by Edward McPherson. Until July 1, 1863 these woods provided shade for Herbst’s eleven head of cattle, wood for various needs around the farm, and some income. Because of the level of human and animal activity in these woods they were free of undergrowth, except for where they came up against Willoughby Run, a sluggish stream that meandered along their western border. Along this stream willows and brush grew thickly.1 Although Confederate troops passed down the Mummasburg road on June 26 on their way to Gettysburg, either Herbst’s farm was too far off the path of their march, or he was clever about hiding his livestock, for he suffered no losses. His luck at avoiding damage or loss from the Confederate invasion of Pennsylvania began to run out on June 30. It was known that a large force of Confederates had occupied Cashtown on June 29, causing a stir of uneasiness. William Comfort and David Finnefrock, the tenant farmers on the Emmanuel Harmon farm, Herbst’s neighbor west of Willoughby Run, chose to take their horses away to protect them. Herbst and John Slentz, the tenant who farmed the McPherson farm, apparently decided to try their chances and remained on their farms, thinking they stood a better chance of protecting their property if they remained.2 On the morning of June 30 a large Confederate infantry brigade under the command of General James J. -

The Gettysburg Campaign: a Contemporary Account by Whitelaw Reid

I The Gettysburg Campaign: A Contemporary Account by Whitelaw Reid Assignment 1863, June 18 From Philadelphia “Pennsylvania invaded!” “Harrisburg expected to fall!” “Lee’s whole army moving through Chambersburg in three grand columns of attack!” And so on for quantity. Such were the pleasing assurances that began to burst on us in the West on Tuesday morning. All Pennsylvania seemed to be quivering in spasms over the invasion. Pittsburgh suspended business and went to fortifying; veracious gentlemen along the railroad lines and in little villages of the interior rushed to the telegraph offices and did their duty to their country by giving their fears to the wings of the lightning. I was quietly settling myself in comfortable quarters at the Neil House to look on at the counterpart of last week’s Vallandigham Convention1 when dispatches reached me, urging an immediate 1 Reid’s reference is to the Ohio state Democratic convention, which convened in Columbus on June 11 and nominated Clement L. Vallandigham for the gover- norship. A leader of the northern Peace Democrats (often called Copperheads), Vallandigham had been arrested for treason on May 5, 1863, and, following banish- ment to Confederate lines, took up exile in Canada that July. The peace movement in the North gained thousands of adherents in the spring of 1863. 99781405181129_4_001.indd781405181129_4_001.indd 1 99/9/2008/9/2008 88:02:01:02:01 PPMM 2 Two Witnesses at Gettysburg departure for the scene of action. I was well convinced that the whole affair was an immense panic, but the unquestioned movements of Lee and Hooker gave certain promise to something; and besides, whether grounded or groundless, the alarm of invasion was a subject that demanded attention.2 And so, swallowing my disgust at the irregular and unauthorized demonstrations of the rebels, I hastened off. -

The Railroad Cut Reconsidered

7KH5DLOURDG&XW5HFRQVLGHUHG 5REHUW:6OHGJH Gettysburg Magazine, Number 52, January 2015, pp. 25-40 (Article) 3XEOLVKHGE\8QLYHUVLW\RI1HEUDVND3UHVV DOI: 10.1353/get.2015.0010 For additional information about this article http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/get/summary/v052/52.sledge.html Accessed 14 Oct 2015 15:30 GMT The Railroad Cut Reconsidered Robert W. Sledge Th e story of the battle in the railroad cut northwest ing just to their north and began to turn to face the of Gettysburg has been told from several perspec- oncoming southerners. In the meantime, another tives. Th e events of the half hour or so at midday, of Wadsworth’s brigades had come onto the fi eld July 1, 1863, have received so much detailed analysis and entered McPherson’s woods south of the pike. that another article on the subject may seem redun- Th ey were the Black Hats, Brig. Gen. “Long Sol” dant, but there are several matters that could still be Meredith’s famous Iron Brigade of the West. Four of open to reconsideration. these regiments quickly clashed in mortal struggle Th e Battle of Gettysburg began when Maj. Gen. with Archer’s men. Th e Iron Brigade’s other regi- Henry Heth dispatched two Confederate brigades ment, the Sixth Wisconsin, augmented by the Iron toward the town of Gettysburg from his base at Brigade Guard of some one hundred men, was at Cashtown to probe the Union positions. Led by fi rst held in reserve but now double- timed north to Brig. Gen. James J. Archer south of the Cashtown head off the oncoming attack of Davis. -

Collection 1805.060.021: Photographs of Union and Confederate Officers in the Civil War in America – Collection of Brevet Lieutenant Colonel George Meade U.S.A

Collection 1805.060.021: Photographs of Union and Confederate Officers in the Civil War in America – Collection of Brevet Lieutenant Colonel George Meade U.S.A. Alphabetical Index The Heritage Center of The Union League of Philadelphia 140 South Broad Street Philadelphia, PA 19102 www.ulheritagecenter.org [email protected] (215) 587-6455 Collection 1805.060.021 Photographs of Union and Confederate Officers - Collection of Bvt. Lt. Col. George Meade U.S.A. Alphabetical Index Middle Last Name First Name Name Object ID Description Notes Portrait of Major Henry L. Abbott of the 20th Abbott was killed on May 6, 1864, at the Battle Abbott Henry L. 1805.060.021.22AP Massachusetts Infantry. of the Wilderness in Virginia. Portrait of Colonel Ira C. Abbott of the 1st Abbott Ira C. 1805.060.021.24AD Michigan Volunteers. Portrait of Colonel of the 7th United States Infantry and Brigadier General of Volunteers, Abercrombie John J. 1805.060.021.16BN John J. Abercrombie. Portrait of Brigadier General Geo. (George) Stoneman Chief of Cavalry, Army of the Potomac, and staff, including Assistant Surgeon J. Sol. Smith and Lieutenant and Assistant J. Adjutant General A.J. (Andrew Jonathan) Alexander A. (Andrew) (Jonathan) 1805.060.021.11AG Alexander. Portrait of Brigadier General Geo. (George) Stoneman Chief of Cavalry, Army of the Potomac, and staff, including Assistant Surgeon J. Sol. Smith and Lieutenant and Assistant J. Adjutant General A.J. (Andrew Jonathan) Alexander A. (Andrew) (Jonathan) 1805.060.021.11AG Alexander. Portrait of Captain of the 3rd United States Cavalry, Lieutenant Colonel, Assistant Adjutant General of the Volunteers, and Brevet Brigadier Alexander Andrew J. -

When We Talk About Masonic History, It Is Clear That the Lodges of the Grand Lodge of Virginia Clearly Have Plenty of It

A GAVEL AT GETTYSBURG: FREEMASONS HONORS THE BATTLE’S 150TH ANNIVERSARY When we talk about Masonic History, it is clear that the Lodges of the Grand Lodge of Virginia clearly have plenty of it. Let’s face it, many of her Lodges (and the Grand Lodge of Virginia itself) were already established well before the unification of the Ancients and the Moderns where they formed under the United Grand Lodge of England. Some of Virginia’s oldest Lodges could say that they were present before the schism which would rend asunder these brethren of the Ancients and Moderns as well. From their struggles to maintain themselves through the years and across the many conflicts of their nations; from the French and Indian War, to the American Revolution, to the War of 1812, the various Indian Wars, to the Mexican War and even beyond the great American Civil War, Virginia Masons have stood with their Masonic brethren throughout this nation, and the world to at times shine as the last beacon of hope, when all other lights seemed to have failed the people of this Earth. In late June, I called up my dear brother, Worshipful Chris Chrzanowski, and while talking to him, he informs me that Henry Lodge No. 57 will be hosting a bus ride from Fairfax, Virginia to Gettysburg, Pennsylvania in recognition of the 150th Anniversary of the Battle of Gettysburg. As one who loves history and is a part of the Grand Lodge’s Committee on History, I asked him to send me more information and he sent out an email with the following information: Henry Lodge No 57 invites you to join us for a day back in history. -

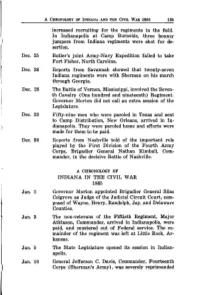

The Ac- Ait Urth Red Om- Ent, Rty- One Son, , N. First Un

A CF~RONOLOGYOF INDIANA AND THE CIVIL WAR 1865 135 art of the government in the increased recruiting for the regiments in the field. uded and the cases submitted In Indianapolis at Camp Bnmside, three bounty jumpers from Indiana regiments were shot for de- sertion. ndred rebel prisoners arrived .e quartered in Camp Morton. Dec. 25 Butler's joint Army-Navy Expedition failed to take Fort Fisher, North Carolina. nt issued its seventh call for 00,000 men for 1, 2, or 3 years Dec. 26 Reports from Savannah showed that twenty-seven one of the editors of the De- Indiana regiments were with Sherman on his march Eagle, was arrested by the through Georgia. at district for treasonous ac- Dec. 28 The Battle of Vernon, Mississippi, involved the Seven- in a military prison to await th Cavalry (One hundred and nineteenth) Regiment. Governor Morton did not call an extra session of the 'orty-third Regiment, John F. Legislature. e hundred and forty-fourth e, Commander; One hundred Dec. 29 Fifty-nine men who were paroled in Texas and sent ent, John A. Platter, Com- to Camp Distribution, New Orleans, arrived in In- and forty-seventh Regiment, dianapolis. They were paroled home and efforts were ~der;One hundred and forty- made for them to be paid. s Burgess, Commander; One Dec. 30 Reports from Nashville told of the important role th Regiment, R. N. Hudson, played by the First Division of the Fourth Army red and fiftieth Regiment, N. Corps, Brigadier General Nathan Kimball, Com- ; One hundred and fifty-first mander, in the decisive Battle of Nashville.