Militancy and Solidarity on the Docks in the 1960S 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1Contents FSC Contents.Qxd

22REVIEWS (Composite)_REVIEWS (Composite).qxd 2/11/2019 11:39 AM Page 123 123 Reviews Latin America Grace Livingstone, Britain and the Dictatorships of Argentina and Chile 19731982, Palgrave Macmillan, 2018, 292 pages, ISBN 9783319782911, £16 During the twentieth century, Latin America was the scene of numerous military coups which established oppressive dictatorships notorious for their abuse of democratic and human rights. This book is a detailed study of the policies adopted by Britain towards two of them – in Chile and Argentina. On 11 September 1973, Augusto Pinochet, the head of Chilean armed forces, launched a coup against the democratically elected socialist president, Salvador Allende. He bombed the presidential palace, fired on and arrested thousands of Allende supporters and other leftwingers, and shut down all democratic institutions. In Argentina on 26 March 1976, the widowed third wife of former dictator Juan Peron, Isabella Peron, who had been elected president, was overthrown by the army, which closed down the Congress, banned political parties, dissolved the Supreme Court, and arrested thousands of political activists including former ministers. In the cases of both Chile and Argentina, the British Foreign Office and leading ambassadorial staff – despite theoretical commitments to democracy – recommended recognition of the military juntas established and downplayed reports of human rights infringements. Grace Livingstone attributes this to the class basis of the personnel involved. She states that, in 1950, 83% of Foreign Office recruits attended private schools and the figure was still 68% ten years later. In 1980, 80% of ambassadors and top Foreign Office officials had attended feepaying schools. -

Joseph Hansen Papers

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf78700585 No online items Register of the Joseph Hansen papers Finding aid prepared by Joseph Hansen Hoover Institution Archives 434 Galvez Mall Stanford University Stanford, CA, 94305-6003 (650) 723-3563 [email protected] © 1998, 2006, 2012 Register of the Joseph Hansen 92035 1 papers Title: Joseph Hansen papers Date (inclusive): 1887-1980 Collection Number: 92035 Contributing Institution: Hoover Institution Archives Language of Material: English Physical Description: 109 manuscript boxes, 1 oversize box, 3 envelopes, 1 audio cassette(46.2 linear feet) Abstract: Speeches and writings, correspondence, notes, minutes, reports, internal bulletins, resolutions, theses, printed matter, sound recording, and photographs relating to Leon Trotsky, activities of the Socialist Workers Party in the United States, and activities of the Fourth International in Latin America, Western Europe and elsewhere. Physical Location: Hoover Institution Archives Creator: Hansen, Joseph, Access The collection is open for research; materials must be requested at least two business days in advance of intended use. Publication Rights For copyright status, please contact the Hoover Institution Archives. Preferred Citation [Identification of item], Joseph Hansen papers, [Box no., Folder no. or title], Hoover Institution Archives. Acquisition Information Acquired by the Hoover Institution Archives in 1992. Accruals Materials may have been added to the collection since this finding aid was prepared. To determine if this has occurred, find the collection in Stanford University's online catalog at http://searchworks.stanford.edu . Materials have been added to the collection if the number of boxes listed in the online catalog is larger than the number of boxes listed in this finding aid. -

Trotskyists Debate Ireland Workers’ Liberty Volume 3 No 45 October 2014 £1 Reason in Revolt Trotskyists Debate Ireland 1939, Mid-50S, 1969

Trotskyists debate Ireland Workers’ Liberty Volume 3 No 45 October 2014 £1 www.workersliberty.org Reason in revolt Trotskyists debate Ireland 1939, mid-50s, 1969 1 Workers’ Liberty Trotskyists debate Ireland Introduction: freeing Marxism from pseudo-Marxist legacy By Sean Matgamna “Since my early days I have got, through Marx and Engels, Slavic peoples; the annihilation of Jews, gypsies, and god the greatest sympathy and esteem for the heroic struggle of knows who else. the Irish for their independence” — Leon Trotsky, letter to If nonetheless Irish nationalists, Irish “anti-imperialists”, Contents Nora Connolly, 6 June 1936 could ignore the especially depraved and demented charac - ter of England’s imperialist enemy, and wanted it to prevail In 1940, after the American Trotskyists split, the Shachtman on the calculation that Catholic Nationalist Ireland might group issued a ringing declaration in support of the idea of gain, that was nationalism (the nationalism of a very small 2. Introduction: freeing Marxism from a “Third Camp” — the camp of the politically independent part of the people of Europe), erected into absolute chauvin - revolutionary working class and of genuine national liberation ism taken to the level of political dementia. pseudo-Marxist legacy, by Sean Matgamna movements against imperialism. And, of course, the IRA leaders who entered into agree - “What does the Third Camp mean?”, it asked, and it ment with Hitler represented only a very small segment of 5. 1948: Irish Trotskyists call for a united replied: Irish opinion, even of generally anti-British Irish opinion. “It means Czech students fighting the Gestapo in the The presumption of the IRA, which literally saw itself as Ireland with autonomy for the Protestant streets of Prague and dying before Nazi rifles in the class - the legitimate government of Ireland, to pursue its own for - rooms, with revolutionary slogans on their lips. -

Brendan Behan Interviews and Recollections

Brendan Behan Interviews and Recollections Volume 1 Also by E. H. Mikhail The Social and Cultural Setting of the 189os John Galsworthy the Dramatist Comedy and Tragedy Sean O'Casey: A Bibliography of Criticism A Bibliography of Modern Irish Drama 1899-1970 Dissertations on Anglo-Irish Drama The Sting and the Twinkle: Conversations with Sean O'Casey (co-editor with John O'Riordan) J. M. Synge: A Bibliography of Criticism Contemporary British Drama 195o-1976 J. M. Synge: Interviews and Recollections (editor) W. B. Yeats: Interviews and Recollections (two volumes) (editor) English Drama I900-1950 Lady Gregory: Interviews and Recollections (editor) Oscar Wilde: An Annotated Bibliography of Criticism Oscar Wilde: Interviews and Recollections (two volumes) (editor) A Research Guide to Modern Irish Dramatists The Art of Brendan Behan Brendan Behan: An Annotated Bibliography of Criticism An Annotated Bibliography of Modern Anglo-Irish Drama Lady Gregory: An Annotated Bibliography of Criticism BRENDAN BEHAN Interviews and Recollections Volume 1 Edited by E. H. Mikhail M Macmillan Gill and Macmillan Selection and editorial matter © E. H. Mikhail 1982 Softcover reprint of the hardcover 1st edition 1982 978-0-333-31565-1 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without permission First published 1g82 by THE MACMILLAN PRESS LTD London and Basingstoke Companies and representatives throughout the world ISBN 978-1-349-06015-3 ISBN 978-1-349-06013-9 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-1-349-06013-9 Published in Ireland by GILL AND MACMILLAN LTD Goldenbridge Dublin 8 Contents Acknowledgements Vll Introduction lX A Note on the Text Xll Chronological Table Xlll INTERVIEWS AND RECOLLECTIONS The Golden Boy Stephen Behan I Schooldays 2 Moving Out Dominic Behan 2 A Bloody Joke Dominic Behan 7 Dublin Boy Goes to Borstal 9 The Behan I Knew Was So Gentle C. -

Vol. 3 No. 4, August–September 1958

Vol. 3 AUGUST"SEPTEMBER 1958 No.4 SOCIALISTS AND TRADE UNIONS Three Conferences 97 'Export of Revolution' 104 Freedom 011 the Individual 119 Labour's 1951 Defeat '25 . Science and Socialism 128 SUMMER BOOKS_____ -. reviewed by HENRY COLLINS, JOHN DANIELS, TOM KEMP, STANLEY EVANS, DOUGLAS GOLDRING, BRIAN PEARCE and others TWO SHILLINGS 266 Lavender Hill, London S.W. II Editors: John Daniels, Robert Shaw Business Manager: Edward R. Knight Contents EDITORIAL Three Conferences 97 SOt:IALISTS AND THE TRADE UNIONS Brian Behan 98 . 'EXPORT OF REVOLUTION', 19l7-1924 Brian Pearce lO4 FREEDOM OF THE INDIVIDUAL Peter Fryer 119 COMMUNICATIONS Stalinism and the Defeat of the 1945-51 Labour Governments Peter Cadogan 125 Science and Socialism G. N. Anderson 128 SUMMER BOOKS The New Ghana, by J. G. Amamoo Ekiomenesekenigha 109 The First International, ed. and trans. by Hans Gerth Henry Collins 110 Germany and the Revolution in Russia, 1915-1918, ed. by Z. A. B. Zeman B.P. 110 Stalin's C(}rresp~ndence with Churchill, At-tlee, Roosevelt and Truman, 1941-45 Brian Pearce 111 The Economics of Communist Eastern Europe, by Nicolas Spulber Tom Kemp III The Epic Strain in the English Novel, by E. M. W. Tillyard S.F.H. 113 A Victorian Eminence, by Giles St Aubyn K. R. Andrews 114 The Sweet and Twenties, by Beverley Nichols Douglas Goldring 114 Soviet Education for Science and Technoiogy, by A. G. Korol John Daniels ll5 Seven Years Solitary, by Edith Bone J.C.D. 115 The Kingdom of Free Men, by G. Kitson Clark Stanley Evans 116 On Religion, by K. -

PAPERS of SÉAMUS DE BÚRCA (James Bourke)

Leabharlann Náisiúnta na hÉireann National Library of Ireland Collection List No. 74 PAPERS OF SÉAMUS DE BÚRCA (James Bourke) (MSS 34,396-34,398, 39,122-39,201, 39,203-39,222) (Accession Nos. 4778 and 5862) Papers of the playwright Séamus De Búrca and records of the firm of theatrical costumiers P.J. Bourke Compiled by Peter Kenny, Assistant Keeper, 2003-2004 Contents INTRODUCTION 12 The Papers 12 Séamus De Búrca (1912-2002) 12 Bibliography 12 I Papers of Séamus De Búrca 13 I.i Plays by De Búrca 13 I.i.1 Alfred the Great 13 I.i.2 The Boys and Girls are Gone 13 I.i.3 Discoveries (Revue) 13 I.i.4 The Garden of Eden 13 I.i.5 The End of Mrs. Oblong 13 I.i.6 Family Album 14 I.i.7 Find the Island 14 I.i.8 The Garden of Eden 14 I.i.9 Handy Andy 14 I.i.10 The Intruders 14 I.i.11 Kathleen Mavourneen 15 I.i.12 Kevin Barry 15 I.i.13 Knocknagow 15 I.i.14 Limpid River 15 I.i.15 Making Millions 16 I.i.16 The March of Freedom 16 I.i.17 Mrs. Howard’s Husband 16 I.i.18 New Houses 16 I.i.19 New York Sojourn 16 I.i.20 A Tale of Two Cities 17 I.i.21 Thomas Davis 17 I.i.22 Through the Keyhole 17 I.i.23 [Various] 17 I.i.24 [Untitled] 17 I.i.25 [Juvenalia] 17 I.ii Miscellaneous notebooks 17 I.iii Papers relating to Brendan and Dominic Behan 18 I.iv Papers relating to Peadar Kearney 19 I.v Papers relating to Queen’s Theatre, Dublin 22 I.vi Essays, articles, stories, etc. -

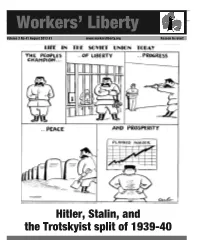

Hitler, Stalin, and the Trotskyist Split of 1939-40 the Trotskyist Split of 1939-40

The Trotskyist split of 1939-40 Workers’ Liberty Volume 3 No 41 August 2013 £1 www.workersliberty.org Reason in revolt Hitler, Stalin, and the Trotskyist split of 1939-40 The Trotskyist split of 1939-40 From 1935: the official Communist Parties across the world, and Stalin’s Russian government, agitate for an alliance of “the democracies” (taken to include Reclaiming our history Russia) By Sean Matgamna Yugoslavia, and looked to the USSR, under the Stalinist bu - 23 August 1939: “Hitler-Stalin pact” signed between reaucracy, to lead a great world-wide revolution against cap - Nazi Germany and Russia. George Santanyana’s aphorism, “Those who do not learn italism in the course of the World War 3 which they saw as from history are likely to repeat it”, is not less true for having inevitable. The Trotskyists had become “Brandlerites”. 1 September 1939: Germany invades Poland. Russia become a cliché. And those who do not know their own his - In the 1960s the British SWP prided itself on not being will invade from the east on 17 September. Hitler and tory cannot learn from it. Leninist, which it explained as not being like the Healy or - Stalin agree to partition Poland The history of the Trotskyist movement — that is, of or - ganisation. In the 1970s it was transformed into a “Leninist” ganised revolutionary Marxism for most of the 20th century organisation and into an organisation more like the Healyites 3 September 1939: Britain and France declare war — is a case in point. To an enormous extent the received his - of the 1960s than its old self. -

Since Brendan Behan Died, a Lot of Stories Have Grown up About Him, Maybe Too Many

Since Brendan Behan died, a lot of stories have grown up about him, maybe too many. Some of these are true, some have been juiced up, and some are mythical. They've been tailored to fit the man that the tellers think he was,. Throw a stone in Dublin and the chances are that it will hit someone who. has a Behan tale to tell - usually at closing time in some inner-city pub. This book, written with the active participation of one of the people who knew Brendan Behan best - his brother Brian, aims to cut through the mythology and get at the real Brendan Behan. In Brian's own words: "Many have tried to define the chameleon character that is Brendan Behan, most using cliches like 'rumbustious', 'rowdy', 'brawling' or 'boozy', but the real Brendan was as complex as any of us, a unique composite of scallywag and angel" Behan wrote with a passion and a unique insight into Dublin life, and into life in general, and his best works - including Borstal Boy and The Quare Fellow - are currently enjoying a renaissance of sorts. As BBC political editor John Cole wrote recently in The Guardian: "A wave of Behanism is haunting Europe". The book analyses Behan through his work and through his activities, and in particular through his relationship with his brother, and is the first truly accurate, authentic portrayal of this famous Irish writer, who died well before his time, and who left the literary world the poorer for his passing. The Authors: Brian Behan is the brother of Brendan Behan, and also a playwright in his own right. -

University of Alberta Brendan Beban's Dramatic Use

UNIVERSITY OF ALBERTA "Who's The Bloody Baritone?" BRENDAN BEBAN'S DRAMATIC USE OF SONG. A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fuifiilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. Department of Drama Edmonton, Alberta Spring 1998 National Library Biblioth ue nationale du Cana2 a Ac uisitions and Acquisitions et ~idiogra~hicSeMces setMces bibliographiques 385 Wellington Street 395, ~e Wdlingîon OnawaûtU K1AW OnswaON KIAW Ceneda Canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant a la National Library of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or seil reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of tbis thesis in microfonn, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/film, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts fiom it Ni la thése ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otbewise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits saas son ~ermission. autorisation. This thesis examines Brendan Behan's use of Song and music in his plays The @lare Feilow, An Giall, and The Hostage. In these plays Behan utilizes song to such an extent one cannot overlook the integrai nature of musical interludes within the body of the plays. A wide variety of songs and musical interludes are interjected into the action of these three plays and, as such, they often satirically comment upon the action of the play while also presenting the audience with a more perceptive understanding of the characters who sing them. -

Labour Affairs Incorporating the Labour and Trade Union Review

Labour Affairs Incorporating the Labour and Trade Union Review No. 287 - May 2018 Price £2.00 (€ 3.00) Labour And Antisemitism Antisemitism is being used by the right wing within the definition which ought to be narrowed down to a simple Parliamentary Labour Party to undermine Corbyn, while message: antisemitism is a hatred of Jews simply because the Tories shelter behind the antisemitism allegations in of their racial origin and religious practices. order to cover up their Brexit divisions and their abysmal Corbyn’s PLP critics, while not accusing him directly social policies which are having such a devastating effect of antisemitism, have pointed at what they see as his on hundreds of thousands of families. In their eagerness lack of leadership on the issue. This manifests itself in to attack Corbyn at every opportunity, the Labour the slow progress made in dealing with the antisemitism oppositionists and the Tories make ideal bedfellows. they believe is endemic in the party. They argue that The International Definition of Antisemitism, (IDA), failure so far to carry out the recommendations in the agreed at a conference of the Berlin-based International Chakrabarti report, (an inquiry into antisemitism and other Holocaust Remembrance Alliance in May 2016 states: forms of racism in the Labour Party), published in June “Antisemitism is a certain perception of Jews, which 2016, is evidence of this. The report, which made twenty may be expressed as hatred toward Jews. Rhetorical and recommendations, concluded that Labour is not overrun physical manifestations of antisemitism are directed by antisemitism or other forms of racism, but there is an toward Jewish or non-Jewish individuals and/or their “occasionally toxic atmosphere.” This is now being given property, toward Jewish community institutions and top priority under the supervision of the newly appointed religious facilities. -

The Socialist Labour League

5 THE SOCIALIST LABOUR LEAGUE The SLL (Socialist Labour League) was founded in 1959, and was a deliberate attempt to transform ourselves from the small circle the Group that we had been. The initial recruitment was enormous. Our willingness to take on the right wing and the trade union leadership attracted many to our ranks. A number of the contacts we had made organising the National Rank And File conference applied for membership, and since 1956 we had recruited a number of militants from the ranks of the Communist Party. One such comrade was Brian Behan, brother of the author Brendan Behan and leader of many a struggle on the London building sites. In 1960 Brian Behan proposed that we should leave the Labour Party and launch ourselves as an open workers party. We held a Yorkshire aggregate of all our members (as did all other areas) to discuss this question. Behan did have some support in the area, but the proposal for the open party was decisively rejected. But neither were we going to surrender the Newsletter and the SLL in order to snuggle up nice and cosy as a pressure group in the Labour Party. We chose instead to take the fight to them. However those who supported the call for an open revolutionary party ended up diving into the deep end of the Labour Party pool and came up spluttering. It was really an example of how sectarianism and opportunism can come from the same source. Over the next years we went on the offensive. We took on Gaitskell and Nye Bevan (who had completely gone over to the 84 STAYING RED Moscow line). -

Westminsterresearch 'Through Trade Unionism You Felt a Belonging – You

WestminsterResearch http://www.westminster.ac.uk/westminsterresearch ‘Through Trade Unionism you felt a belonging – you belonged’: Collectivism and the Self-Representation of Building Workers in Stevenage New Town McGuire, C., Clarke L. and Wall, C. This is an author's accepted manuscript of an article published in the Labour History Review 81 (3), pp. 211-236 2016. The final definitive version is available online at: https://dx.doi.org/10.3828/lhr.2016.11 The WestminsterResearch online digital archive at the University of Westminster aims to make the research output of the University available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the authors and/or copyright owners. Whilst further distribution of specific materials from within this archive is forbidden, you may freely distribute the URL of WestminsterResearch: ((http://westminsterresearch.wmin.ac.uk/). In case of abuse or copyright appearing without permission e-mail [email protected] ‘Through Trade Unionism you felt a belonging—you belonged’: Collectivism and the Self-Representation of Building Workers in Stevenage New Town When it comes to self-representation of building workers, books are relatively thin on the ground. Of those that have been published, perhaps one of the most colourful was Brian Behan’s 1964 memoir, which included an account of a major strike on Robert MacAlpine’s Shell-Mex site on the South Bank in London in 1958 that resulted in him being jailed and expelled from the Amalgamated Union of Building Trade Workers (AUBTW). 1 Another reasonably well-known memoir was published four years earlier by Donall MacAmlaigh.2 Based on his diaries, MacAmlaigh’s book was an account of his experiences on various civil engineering and building sites in the Midlands and London during the 1950s.