James Labounty

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National Life Stories an Oral History of British

NATIONAL LIFE STORIES AN ORAL HISTORY OF BRITISH SCIENCE Professor Bob Dickson Interviewed by Dr Paul Merchant C1379/56 © The British Library Board http://sounds.bl.uk This interview and transcript is accessible via http://sounds.bl.uk . © The British Library Board. Please refer to the Oral History curators at the British Library prior to any publication or broadcast from this document. Oral History The British Library 96 Euston Road London NW1 2DB United Kingdom +44 (0)20 7412 7404 [email protected] Every effort is made to ensure the accuracy of this transcript, however no transcript is an exact translation of the spoken word, and this document is intended to be a guide to the original recording, not replace it. Should you find any errors please inform the Oral History curators. © The British Library Board http://sounds.bl.uk British Library Sound Archive National Life Stories Interview Summary Sheet Title Page Ref no: C1379/56 Collection title: An Oral History of British Science Interviewee’s surname: Dickson Title: Professor Interviewee’s forename: Bob Sex: Male Occupation: oceanographer Date and place of birth: 4th December, 1941, Edinburgh, Scotland Mother’s occupation: Housewife , art Father’s occupation: Schoolmaster teacher (part time) [chemistry] Dates of recording, Compact flash cards used, tracks [from – to]: 9/8/11 [track 1-3], 16/12/11 [track 4- 7], 28/10/11 [track 8-12], 14/2/13 [track 13-15] Location of interview: CEFAS [Centre for Environment, Fisheries & Aquaculture Science], Lowestoft, Suffolk Name of interviewer: Dr Paul Merchant Type of recorder: Marantz PMD661 Recording format : 661: WAV 24 bit 48kHz Total no. -

Northern Ireland Affairs Committee Oral Evidence: Brexit and the Northern Ireland Protocol, HC 157

Northern Ireland Affairs Committee Oral evidence: Brexit and the Northern Ireland Protocol, HC 157 Wednesday 16 June 2021 Ordered by the House of Commons to be published on 16 June 2021. Watch the meeting Members present: Simon Hoare (Chair); Scott Benton; Mr Gregory Campbell; Stephen Farry; Mary Kelly Foy; Mr Robert Goodwill; Claire Hanna; Fay Jones; Ian Paisley; Bob Stewart. Questions 941-1012 Witnesses I: The Rt Hon. Lord David Frost CMG, Minister of State for the Cabinet Office, and Mark Davies, Deputy Director, Transition Task Force Northern Ireland, Cabinet Office. Examination of witnesses Witnesses: Lord Frost and Mark Davies. Q941 Chair: Good morning, colleagues, and welcome to this session of our inquiry into Brexit and the Northern Ireland protocol. May I ask if any colleagues have any declarations of interest before we begin the meeting? Ian Paisley: I am involved in a legal action against the protocol with a number of commercial entities. Q942 Chair: Thank you. Lord Frost, you heard that, so that is under advisement, as it were. Minister, let me begin by establishing a few basic facts, because I think there is some uncertainty in the media and in the world of politics. Hopefully this will be a sort of quickfire yes or no round to get us into second gear. Could you confirm that Her Majesty’s Government negotiated with the European Union the Northern Ireland protocol? Lord Frost: Thank you, Chairman, and good morning. Before I answer that question, I would like to make one remark up front. It is a pleasure to be here today. -

Geoscience and a Lunar Base

" t N_iSA Conference Pubhcatmn 3070 " i J Geoscience and a Lunar Base A Comprehensive Plan for Lunar Explora, tion unclas HI/VI 02907_4 at ,unar | !' / | .... ._-.;} / [ | -- --_,,,_-_ |,, |, • • |,_nrrr|l , .l -- - -- - ....... = F _: .......... s_ dd]T_- ! JL --_ - - _ '- "_r: °-__.......... / _r NASA Conference Publication 3070 Geoscience and a Lunar Base A Comprehensive Plan for Lunar Exploration Edited by G. Jeffrey Taylor Institute of Meteoritics University of New Mexico Albuquerque, New Mexico Paul D. Spudis U.S. Geological Survey Branch of Astrogeology Flagstaff, Arizona Proceedings of a workshop sponsored by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration, Washington, D.C., and held at the Lunar and Planetary Institute Houston, Texas August 25-26, 1988 IW_A National Aeronautics and Space Administration Office of Management Scientific and Technical Information Division 1990 PREFACE This report was produced at the request of Dr. Michael B. Duke, Director of the Solar System Exploration Division of the NASA Johnson Space Center. At a meeting of the Lunar and Planetary Sample Team (LAPST), Dr. Duke (at the time also Science Director of the Office of Exploration, NASA Headquarters) suggested that future lunar geoscience activities had not been planned systematically and that geoscience goals for the lunar base program were not articulated well. LAPST is a panel that advises NASA on lunar sample allocations and also serves as an advocate for lunar science within the planetary science community. LAPST took it upon itself to organize some formal geoscience planning for a lunar base by creating a document that outlines the types of missions and activities that are needed to understand the Moon and its geologic history. -

Bucharest Meeting Summary

PC 242 PC 17 E Original: English NATO Parliamentary Assembly SUMMARY of the meeting of the Political Committee Plenary Hall, Chamber of Deputies, The Parliament (Senate and Chamber of Deputies) of Romania Bucharest, Romania Saturday 7 and Sunday 8 October 2017 www.nato-pa.int November 2017 242 PC 17 E ATTENDANCE LIST Committee Chairperson Ojars Eriks KALNINS (Latvia) General Rapporteur Rasa JUKNEVICIENE (Lithuania) Rapporteur, Sub-Committee on Gerald E. CONNOLLY (United States) Transatlantic Relations Rapporteur, Sub-Committee on Julio MIRANDA CALHA (Portugal) NATO Partnerships President of the NATO PA Paolo ALLI (Italy) Secretary General of the NATO PA David HOBBS Member delegations Albania Mimi KODHELI Xhemal QEFALIA Perparim SPAHIU Gent STRAZIMIRI Belgium Peter BUYSROGGE Karolien GROSEMANS Sébastian PIRLOT Damien THIERY Luk VAN BIESEN Karl VANLOUWE Veli YÜKSEL Bulgaria Plamen MANUSHEV Simeon SIMEONOV Canada Raynell ANDREYCHUK Joseph A. DAY Larry MILLER Marc SERRÉ Borys WRZESNEWSKYJ Czech Republic Milan SARAPATKA Denmark Peter Juel JENSEN Estonia Marko MIHKELSON France Philippe FOLLIOT Sonia KRIMI Gilbert ROGER Germany Karin EVERS-MEYER Karl A. LAMERS Anita SCHÄFER Greece Spyridon DANELLIS Christos KARAGIANNIDIS Meropi TZOUFI Hungary Mihaly BALLA Karoly TUZES Italy Antonino BOSCO Andrea MANCIULLI Andrea MARTELLA Roberto MORASSUT Vito VATTUONE i 242 PC 17 E Latvia Aleksandrs KIRSTEINS Lithuania Ausrine ARMONAITE Luxembourg Alexander KRIEPS Netherlands Herman SCHAPER Norway Liv Signe NAVARSETE Poland Waldemar ANDZEL Adam BIELAN Przemyslaw -

No. 40. the System of Lunar Craters, Quadrant Ii Alice P

NO. 40. THE SYSTEM OF LUNAR CRATERS, QUADRANT II by D. W. G. ARTHUR, ALICE P. AGNIERAY, RUTH A. HORVATH ,tl l C.A. WOOD AND C. R. CHAPMAN \_9 (_ /_) March 14, 1964 ABSTRACT The designation, diameter, position, central-peak information, and state of completeness arc listed for each discernible crater in the second lunar quadrant with a diameter exceeding 3.5 km. The catalog contains more than 2,000 items and is illustrated by a map in 11 sections. his Communication is the second part of The However, since we also have suppressed many Greek System of Lunar Craters, which is a catalog in letters used by these authorities, there was need for four parts of all craters recognizable with reasonable some care in the incorporation of new letters to certainty on photographs and having diameters avoid confusion. Accordingly, the Greek letters greater than 3.5 kilometers. Thus it is a continua- added by us are always different from those that tion of Comm. LPL No. 30 of September 1963. The have been suppressed. Observers who wish may use format is the same except for some minor changes the omitted symbols of Blagg and Miiller without to improve clarity and legibility. The information in fear of ambiguity. the text of Comm. LPL No. 30 therefore applies to The photographic coverage of the second quad- this Communication also. rant is by no means uniform in quality, and certain Some of the minor changes mentioned above phases are not well represented. Thus for small cra- have been introduced because of the particular ters in certain longitudes there are no good determi- nature of the second lunar quadrant, most of which nations of the diameters, and our values are little is covered by the dark areas Mare Imbrium and better than rough estimates. -

Glossary Glossary

Glossary Glossary Albedo A measure of an object’s reflectivity. A pure white reflecting surface has an albedo of 1.0 (100%). A pitch-black, nonreflecting surface has an albedo of 0.0. The Moon is a fairly dark object with a combined albedo of 0.07 (reflecting 7% of the sunlight that falls upon it). The albedo range of the lunar maria is between 0.05 and 0.08. The brighter highlands have an albedo range from 0.09 to 0.15. Anorthosite Rocks rich in the mineral feldspar, making up much of the Moon’s bright highland regions. Aperture The diameter of a telescope’s objective lens or primary mirror. Apogee The point in the Moon’s orbit where it is furthest from the Earth. At apogee, the Moon can reach a maximum distance of 406,700 km from the Earth. Apollo The manned lunar program of the United States. Between July 1969 and December 1972, six Apollo missions landed on the Moon, allowing a total of 12 astronauts to explore its surface. Asteroid A minor planet. A large solid body of rock in orbit around the Sun. Banded crater A crater that displays dusky linear tracts on its inner walls and/or floor. 250 Basalt A dark, fine-grained volcanic rock, low in silicon, with a low viscosity. Basaltic material fills many of the Moon’s major basins, especially on the near side. Glossary Basin A very large circular impact structure (usually comprising multiple concentric rings) that usually displays some degree of flooding with lava. The largest and most conspicuous lava- flooded basins on the Moon are found on the near side, and most are filled to their outer edges with mare basalts. -

New This Year for Pre-Registered Attendees

NEW THIS YEAR FOR PRE-REGISTERED ATTENDEES LCI will not be mailing convention name badges in advance this year because we’re launching our new express name badge printing at convention. Bring your LCI Official Registration Confirmation Letter and government issued photo-ID, and print your convention name badge in seconds! Conveniently located kiosks will be open beginning Thursday, June 28 at 08:00 at the MGM Grand Garden Arena, New York New York Hotel and Luxor Hotel. Your convention badge now contains “chip” technology and will be scanned at selected events. We debuted the new express name badging system at the Lions Day at the United Nations meeting in New York in March 2018 to rave reviews! See for yourself how easy it is to print a badge in this fun video. GET READY FOR FUN! Here is just a sampling of some of the fun events and activities awaiting you at LCICon inside the MGM Grand Hotel: June 30: International Show Featuring Cirque Dreams A thrilling and dazzling evening awaits with a special performance of Cirque Dreams’ Jungle Fantasy, featuring daring acrobatics, music and more! All Lions and their registered guests are welcome to attend this complimentary show beginning at 19:00 inside MGM’s Grand Garden Arena. June 30: Strides Dance for Diabetes Awareness The fun continues Saturday night immediately after the International Show - join your Lion and Leo friends from around the world, and dance the night away to heighten awareness of diabetes and its complications. Admittance is free and features international music, fun glow props and a cash bar. -

Caesars Palace Las Vegas, Flamingo Las Vegas, the LINQ Promenade and High Roller Observation Wheel Now Open

Caesars Palace Las Vegas, Flamingo Las Vegas, The LINQ Promenade and High Roller Observation Wheel Now Open June 5, 2020 Caesars CEO Tony Rodio, Wayne Newton, Caesar and Cleopatra joined the Caesars Palace reopening; selected outlets now open at The LINQ Promenade; Harrah's Las Vegas set to resume operations on June 5 LAS VEGAS, June 4, 2020 /PRNewswire/ -- In accordance with directives from Nevada Governor Steve Sisolak and the Nevada Gaming Control Board, Caesars Entertainment Corporation (NASDAQ: CZR) ("Caesars Entertainment" or the "Company") has resumed gaming and hospitality operations in Las Vegas at its Caesars Palace and Flamingo Las Vegas properties today, June 4. Additionally, the Company has reopened selected retail and dining outlets along The LINQ Promenade, as well as the High Roller Observation Wheel. On Friday, June 5, at 11 a.m. Pacific Time, Harrah's Las Vegas will also resume operations. **For high-res photos and b-roll, click here** Caesars Palace marked the reopening of its main lobby doors to the public with a special moment on the Roman Plaza featuring Caesars Entertainment headliner Wayne Newton, Caesar and Cleopatra of the resort's Royal Court, and Caesars Entertainment CEO Tony Rodio. Newton was the first to welcome guests and introduced Rodio. Rodio reminisced about all the rich memories in Caesars Palace's 54-year history—from the world- famous boxing matches to iconic entertainment including Newton's show at Cleopatra's Barge, and more. In that time, the resort had never closed its doors up until March 17, 2020, and Rodio did acknowledge the country's continued challenging circumstances. -

Regional Oral History Off Ice University of California the Bancroft Library Berkeley, California

Regional Oral History Off ice University of California The Bancroft Library Berkeley, California Richard B. Gump COMPOSER, ARTIST, AND PRESIDENT OF GUMP'S, SAN FRANCISCO An Interview Conducted by Suzanne B. Riess in 1987 Copyright @ 1989 by The Regents of the University of California Since 1954 the Regional Oral History Office has been interviewing leading participants in or well-placed witnesses to major events in the development of Northern California, the West,and the Nation. Oral history is a modern research technique involving an interviewee and an informed interviewer in spontaneous conversation. The taped record is transcribed, lightly edited for continuity and clarity, and reviewed by the interviewee. The resulting manuscript is typed in final form, indexed, bound with photographs and illustrative materials, and placed in The Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley, and other research collections for scholarly use. Because it is primary material, oral history is not intended to present the final, verified, or complete narrative of events. It is a spoken account, offered by the interviewee in response to questioning, and as such it is reflective, partisan, deeply involved, and irreplaceable. All uses of this manuscript are covered by a legal agreement between the University of California and Richard B. Gump dated 7 March 1988. The manuscript is thereby made available for research purposes. All literary rights in the manuscript, including the right to publish, are reserved to The Bancroft Library of the University of California, Berkeley. No part of the manuscript may be quoted for publication without the written permission of the Director of The Bancroft Library of the University of California, Berkeley. -

America the Beautiful Part 1

America the Beautiful Part 1 Charlene Notgrass 1 America the Beautiful Part 1 by Charlene Notgrass ISBN 978-1-60999-141-8 Copyright © 2020 Notgrass Company. All rights reserved. All product names, brands, and other trademarks mentioned or pictured in this book are used for educational purposes only. No association with or endorsement by the owners of the trademarks is intended. Each trademark remains the property of its respective owner. Unless otherwise noted, scripture quotations are taken from the New American Standard Bible®, Copyright © 1960, 1962, 1963, 1971, 1972, 1973, 1975, 1977, 1995 by the Lockman Foundation. All rights reserved. Used by permission. Cover Images: Jordan Pond, Maine, background by Dave Ashworth / Shutterstock.com; Deer’s Hair by George Catlin / Smithsonian American Art Museum; Young Girl and Dog by Percy Moran / Smithsonian American Art Museum; William Lee from George Washington and William Lee by John Trumbull / Metropolitan Museum of Art. Back Cover Author Photo: Professional Portraits by Kevin Wimpy The image on the preceding page is of Denali in Denali National Park. No part of this material may be reproduced without permission from the publisher. You may not photocopy this book. If you need additional copies for children in your family or for students in your group or classroom, contact Notgrass History to order them. Printed in the United States of America. Notgrass History 975 Roaring River Rd. Gainesboro, TN 38562 1-800-211-8793 notgrass.com Thunder Rocks, Allegany State Park, New York Dear Student When God created the land we call America, He sculpted and painted a masterpiece. -

THE 422 Mps WHO BACKED the MOTION Conservative 1. Bim

THE 422 MPs WHO BACKED THE MOTION Conservative 1. Bim Afolami 2. Peter Aldous 3. Edward Argar 4. Victoria Atkins 5. Harriett Baldwin 6. Steve Barclay 7. Henry Bellingham 8. Guto Bebb 9. Richard Benyon 10. Paul Beresford 11. Peter Bottomley 12. Andrew Bowie 13. Karen Bradley 14. Steve Brine 15. James Brokenshire 16. Robert Buckland 17. Alex Burghart 18. Alistair Burt 19. Alun Cairns 20. James Cartlidge 21. Alex Chalk 22. Jo Churchill 23. Greg Clark 24. Colin Clark 25. Ken Clarke 26. James Cleverly 27. Thérèse Coffey 28. Alberto Costa 29. Glyn Davies 30. Jonathan Djanogly 31. Leo Docherty 32. Oliver Dowden 33. David Duguid 34. Alan Duncan 35. Philip Dunne 36. Michael Ellis 37. Tobias Ellwood 38. Mark Field 39. Vicky Ford 40. Kevin Foster 41. Lucy Frazer 42. George Freeman 43. Mike Freer 44. Mark Garnier 45. David Gauke 46. Nick Gibb 47. John Glen 48. Robert Goodwill 49. Michael Gove 50. Luke Graham 51. Richard Graham 52. Bill Grant 53. Helen Grant 54. Damian Green 55. Justine Greening 56. Dominic Grieve 57. Sam Gyimah 58. Kirstene Hair 59. Luke Hall 60. Philip Hammond 61. Stephen Hammond 62. Matt Hancock 63. Richard Harrington 64. Simon Hart 65. Oliver Heald 66. Peter Heaton-Jones 67. Damian Hinds 68. Simon Hoare 69. George Hollingbery 70. Kevin Hollinrake 71. Nigel Huddleston 72. Jeremy Hunt 73. Nick Hurd 74. Alister Jack (Teller) 75. Margot James 76. Sajid Javid 77. Robert Jenrick 78. Jo Johnson 79. Andrew Jones 80. Gillian Keegan 81. Seema Kennedy 82. Stephen Kerr 83. Mark Lancaster 84. -

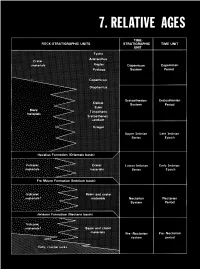

Relative Ages

CONTENTS Page Introduction ...................................................... 123 Stratigraphic nomenclature ........................................ 123 Superpositions ................................................... 125 Mare-crater relations .......................................... 125 Crater-crater relations .......................................... 127 Basin-crater relations .......................................... 127 Mapping conventions .......................................... 127 Crater dating .................................................... 129 General principles ............................................. 129 Size-frequency relations ........................................ 129 Morphology of large craters .................................... 129 Morphology of small craters, by Newell J. Fask .................. 131 D, method .................................................... 133 Summary ........................................................ 133 table 7.1). The first three of these sequences, which are older than INTRODUCTION the visible mare materials, are also dominated internally by the The goals of both terrestrial and lunar stratigraphy are to inte- deposits of basins. The fourth (youngest) sequence consists of mare grate geologic units into a stratigraphic column applicable over the and crater materials. This chapter explains the general methods of whole planet and to calibrate this column with absolute ages. The stratigraphic analysis that are employed in the next six chapters first step in reconstructing