My Drift Title: the Last Japanese Soldier Written By: Jerry D

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Case of Japan

■ First publishing in Annalisa Oboe, Claudia Gualtieri and Robert Bromley (eds), Working and Writing for Tomorrow: Essays in Honour of Itala Vivan. Nottingham, CCCP, 2008 13 Is War an Inevitable Part of History? The Case of Japan a ne day in 1972 Sho¯ ichi Yokoi, a corporal from the Japanese Imperial Army who Ohad somehow become separated from his unit at the time of Japan’s surrender in August 1945, took a short cut across a fi eld of reeds on the island of Guam in the Mariana Islands of the Western Pacifi c. In doing so, he departed from his usual habit of walking in the water along a river, so that his scent would not be picked up by dogs. He was returning from an expedition in search of food to his underground dwelling, concealed by deep jungle from the eyes of villagers, the lights of whose houses he could see from near where he lived. For nearly 28 years he had escaped detection, and after two surviving colleagues died in 1964 he apparently had no contact with any other human being. But his tiny lapse of security in walking straight across the reed fi eld brought to an end his life as a latter-day Robinson Crusoe. He was spotted by hunters, who apprehended him and brought him to the local authorities. This led to him being repatriated to Japan, where the discovery of this ‘living fossil’ from the Asia-Pacifi c War made him an instant media sensation. Schoolchildren throughout the country were fascinated by his strategies for survival. -

USN BD Intelligence Bulletin June 1945 Vol. 2 No. 3

U.S. NAVY BOMB DISPOSAL Intelligence AUGUST 1945 BULLETIN Vol. 2, No. 3 CONTENTS Japanese Bomb Shackles ..... I Jap Hollow Charge Ordnance 6 Japanese Demolition Equip ment ................................. 14 Delayed Action M ine........... 1 8 Booby-Trapped Ammunition Dumps ............................... 1 9 1 Japanese Sabotage Devices.. 2 0 Linear Shaped Charge Attack on VT F u zes..................... 2 5 Theory of Bomb Disposal At tack ................................... 2 9 Modification of BuOrd Re quests ................................ 3 1 Acknowledgments................. 3 2 Notices ......... Inside Back Cover This document is issued to graduates of a course in Bomb Disposal, by the Officer in Charge, Navy Bomb Disposal School, under authority of Bureau of Ordnance letter F4I — 6 (L) of 22 April 1944. It is for in formation and guidance only and is not a Bureau of Ordnance Publication. It should be destroyed when of no further use to Bomb Disposal Personnel. In view of the fact that Bomb Dis into three general classes, namely: posal personnel may be called upon manually operated, explosive oper to remove bombs from crashed and ated, and electro-magnetic operated. captured Japanese bombers, the fol Japanese Navy planes are equipped lowing general information on bomb with either the manually operated or racks and shackles used by the the explosive operated shackles. Army Japanese Air Corps is given. planes are equipped with any one Japanese Army and Navy bomb of three standard electro-magnetic release shackles in standard use fall operated shackles. Typical.Nagy Bomb Rack Showing Arming Vane Stops CONFIDENTIAL attached to the safety lever. Pulling the safety lever disengages a projec tion on the end of the safety lever from a cutaway portion on the cam- | ming surface of the release lever. -

Battle Rifles

Battle Rifles BATTLE RIFLES Argentine Battle Rifles Australian Battle Rifles Austrian Battle Rifles Belgian Battle Rifles Brazilian Battle Rifles British Battle Rifles Canadian Battle Rifles Chinese Battle Rifles Czech Battle Rifles Danish Battle Rifles Dominican Battle Rifles Dutch Battle Rifles Egyptian Battle Rifles Filipino Battle Rifles Finnish Battle Rifles French Battle Rifles German Battle Rifles Hungarian Battle Rifles Indian Battle Rifles Italian Battle Rifles Japanese Battle Rifles Mexican Battle Rifles Norwegian Battle Rifles Pakistani Battle Rifles Russian Battle Rifles Spanish Battle Rifles Swedish Battle Rifles Swiss Battle Rifles Turkish Battle Rifles Uruguayan Battle Rifles US Battle Rifles A-L US Battle Rifles M-Z Yugoslavian Battle Rifles file:///E/My%20Webs/battle_rifles/battle_rifles_2.html[8/9/2020 9:59:42 AM] Argentine Battle Rifles FM Rosario FAL (FSL Series) Notes: The Argentines make several models of the FAL under a license from Belgium’s FN to the Argentine company of FMAP in Rosario; they are collectively known as the FSL series (Fusil Semiautomatico Livano), though several of them are in fact automatic weapons. Argentine versions tend to have slightly different parts measurements than Belgian-made FALs due to local manufacturing methods; therefore, most parts of the FSL series are not interchangeable with more standard FALs. The Fusil Automatico Liviano Modelo IV (FALM IV) is an Argentine-made copy of the Belgian FAL Model 50-00. It is virtually identical to the FAL, but is heavier and has a more substantial muzzle brake. The Fusil Automatico Liviano Modelo Para III (FALMP III) is virtually identical to the FAL 50-64, but again is longer and heavier, with a longer muzzle brake. -

Small Caliber Ammo ID Vol 1

-. t, DST-1160G-514-78-VOL I " O DEFENSE INTELLIGENCE AGENCY EELECTE , J.44LL-CALIbER AMMUNITION IDENTIFICATION GUIDE Jill VOLUME 1 SMALL-ARMS CARTRIDGES UP ki 15 MM (UJ ,.-... tI., .: lAP. , UVý7J) FCl u•r~UBk'L'' 4UL.:I- DIkralUUTIG UNLIMITED "PREPARED BY US ARMY "Y,..i.,fERIEL [)EA'F!•M) ,aT AN, RLADIN"SS OMMAt,!D .'.'R'-GN SCIENCE AND TECH.NIOLOGY CENiIF~ ,. __ . .. .. ._.--. .,----..-. ... --.-... , .... R. T. Hutngo Vc111ma 197 Smell-Armsartidges Uptuf Datme(U Novernlwr 1977 ThiiS PUbliC.itiuii SUPC-(&pcsd SCC -68 i.i a I )cpartniin nE )iD fe ns~[it IlCI~g1ciic C CL .11unn C pr ,in.r, d 1,% Ii UILX11',11 S WIIALC anjild1CIIoIlog CA-tter, tJS Arwy Maicricl DevdqI[1cnt .n I~ch~~n:Cinnaid.~dapprowe b% tho )cpiucv D;ri t~ir furA. S(it'ittitil and TcdIiiical I.tehgllgeicof dthe I)cfciisc Ingclligncir Ageiilcx )ViA I\'I([ P1UBLIC: KIFLASI.: IDISTIIBltt ION (INLIMI'IIUIA) (IRce:%.c ISI.111K) -Z PREFACE This guide outlin&:s a systematic procedure fur identifying milt..rv c~rtgidgL :. e c.. rtridge designiation, country of nianufactuve. and--to a large cxtent-functionial 'bullet cyc~c kVcs'-;ncd Cor usc by persons who may not be familiar with small-arms ammunition, it pirovides L'.wsa inioniation on car-tridge types, construction, and terminology as well as more detailed identification dALa. This guide covers military cartridges in calbrs of 15 mim and below-as well as sevcra! rLllt.cd patamilitary cr target cartridges- that have been mwizufacturcd or used since 1930. Although sm if thec cartridges ini this guide arc obsolete in the country of manufacture, they are included because they were madk: in such large quantities that c . -

Aussie Manual

Fighting for Oz Manual for New Troops in the Pacific Theater of Operations © John Comiskey & Dredgeboat Publications, 2003 The Australian Imperial Force (AIF) When World War II began, Australia answered the call. Many of the men volunteering to fight had fathers that fought in World War I with the five divisions of the First AIF in the Australia-New Zealand Army Corps (ANZACs). As a recognition of the achievements of the ANZACs in World War I, the Second AIF divisions began with the 6th Division and brigades started with the 16th Brigade. At the beginning of the war, only the 6th Division was formed. Two brigades of the 6th went to England, arriving in January 1940. The third brigade of the 6th was sent to the Middle East. The disaster in France that year drove more Australians to volunteer, with the 7th, 8th and 9th Divisions formed in short order. The 9th Division was unique in this process The Hat Badge of the AIF. The sunburst in th th the background was originally a hedge of because it was formed with elements of the 6 & 7 Divisions in bayonets. Palestine. The 2/13th Battalion The 2/13th Battalion was originally assigned to the 7th Division, but was transferred to the new 9th Division while in the Mediterranean. The 9th Division fought hard in the Siege of Tobruk (April-December 1941), earning the sobriquet “The Desert Rats.” The 2/13th Battalion was unique in that they were in Tobruk for the eight months of the siege, the other battalions of the 9th being replaced with other Commonwealth troops. -

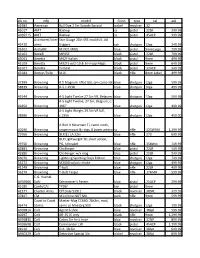

Stk No Mfg Model Finish Type Cal Ask 41983 American Bull Dog 2.5In

stk no mfg model finish type cal ask 41983 American Bull Dog 2.5in Suicide Special nickel revolver .32 42017 AMT Backup ss pistol .22LR 299.99 A939715 AMT Backup ss pistol .45ACP 399.99 Aramberri/Inter Star Guage 28in SXS mod/full, dbl 42470 arms triggers cch shotgun 12ga 249.99 35302 Astra/IIC M1921 (400) blue pistol 9mmLargo 299.99 43163 Benelli MP95E black pistol .22LR 799.99 43041 Beretta M92F Italian black pistol 9mm 499.99 43109 Beretta M92FS w/2-10 & 6 Hi-cap Mags black pistol 9mm 649.99 43107 Beretta Tomcat black pistol .32ACP 349.99 43184 Bertier/Tulle M16 black rifle 8mm Lebel 499.99 37399 Browning A 5 Magnum rifled bbl, syn camo stk blue shotgun 12ga 599.99 38839 Browning A-5 c.1938 blue shotgun 16ga 499.99 41944 Browning A-5 Light Twelve 27.5in VR, Belgium blue shotgun 12ga 599.99 A-5 Light Twelve, 27.5in, Belgium, c. 42850 Browning 1967 blue shotgun 12ga 499.99 A-5 Light Weight 29.5in VR full, 38986 Browning c.1956 blue shotgun 12ga 450.00 A-Bolt II Mountain Ti, camo stock, 40196 Browning scope mount & rings, 8 boxes ammo ss rifle .325WSM 1,399.99 29766 Browning BLR 81 LA 22in blue rifle .270 699.99 BLR Lightweight '81 short action, 29756 Browning PG, Schnabel blue rifle .358Win 749.99 42881 Browning Challenger blue pistol .22LR 549.99 42880 Browning Challenger w/x mag blue pistol .22LR 549.99 43070 Browning Lightning Sporting Clays Edition blue shotgun 12ga 749.99 35272 Browning M2000 w/poly choke blue shotgun 12ga 499.99 41249 Browning T-bolt blue rifle .22LR 499.99 36279 Browning T-Bolt Target blue rifle .17HMR 599.99 C.G. -

Technical * Intelligence Summary

COPY No. 179 TECHNICAL * INTELLIGENCE SUMMARY No. 21 JANUARY 1945 Prepared by the General Staff Intelligence and issued under the direction of the Commander- in-Chief, Headquarters, Australian Military Forces L.H.Q. MISC 9529 Printed by Authority : McLaren de Co. Pty. Ltd., Melbourne. AUSTRALIAN MILITARY FORCES TECHNICAL INTELLIGENCE SUMMARY NOS. 1-21 TABLE OF CONTENTS JAPANESE EQUIPMENT PART I WEAPONS SUMMARY NO. 6.5 mni T.’eiji 44 Rif la .......................................... 6; 9 6.5 Model 97 Rifle .......................................... 14 6.5 mm Model 38 Rifle .......................................... 14 6.5 mm Type 96 LMG .......................................... 1 6.5 mm Third Year Type LMG ................................ 19 6.5 mm Taigho 11 LMG .......................................... 2 7.63 mm Solothurn SMG .......................................... 1 7.7 ran Type 99 Rifle .......................................... 11 7.7 mm Type 2 Paratroop Rifle ...................... 21 7.7 mm Type 92 (JUKI) MMG ................................ 1, 10 7,7 ram AFV Type LMG .......................................... 1, 2 7.7 mm Vickers Type A/C MG................................ 6 7.7 ram Type 92 Lewis MG.......................................... 12 7.92 min Type 100 Double Barrel A/C MG 12 7.92 ram Type 88 Flexible MG................................ 13 8 mm Automatic Pistol .......................................... 1 8 mm Type 100 Paratroop SMG ....................... 21 9 mm Webley Type Revolver ............................... -

Koleksi Cerita, Novel, & Cerpen Terbaik Teruo Nakamura, Tentara

ILMUIMAN.NET: Koleksi Cerita, Novel, & Cerpen Terbaik Mini Biografi (16+). 2018 (c) ilmuiman.net. All rights reserved. Berdiri sejak 2007, ilmuiman.net tempat berbagi kebahagiaan & kebaikan.. Seru. Ergonomis, mudah, & enak dibaca. Karya kita semua. Terima kasih & salam. *** Teruo Nakamura, Tentara Jepang Dari Morotai Pendahuluan Di internet, banyak cerita tentang Prajurit (Private) Teruo Nakamura. Dia juaranya, dari tentara Jepang yang terus bersembunyi sejak selesainya perang dunia kedua. Tapi cerita Nakamura ini agak tragis. Salah satu sumber artikel untuk cerita ini, adalah dari Majalah Time online, dicuplik dari Time edisi 13 Januari 1975 dan wikipedia.com. Berikut ini, adalah terjemahannya, dilengkapi cerita dari sumber-sumber lain. Ada kesaksian dari saksi mata, responden RRI yang diwawancara Republika. Tahun 1974, apa yang terjadi di Indonesia? Saat itu, kita baru mulai 'bangkit kembali', dari gegeran pergantian era orde lama ke orde baru. Mohon maklum, di akhir masa orde lama, Indonesia kena embargo dari negeri-negeri barat, disebabkan terlalu pro komunis, terus ada konfrontasi dengan Malaysia segala, dan segala rupa. Perekonomian ancur-ancuran. Pegawai negeri di segenap pelosok.. itu sering gajian-nya dibon. Sandang-pangan susah. Nah, keadaan mulai berubah, setelah muncul orde baru yang amat pro barat (dan anti komunis). Berkat sikap baru pro-barat ini,.. bantuan-bantuan bermunculan. Dari barat. Jelas-lah. Kalo pro-barat, terus bantuannya datang dari Nyi Roro Kidul, itu cerita mistik, ya? Kebanyakannya bantuan berupa hutang, tapi rakyat gak peduli, mau hutang kek, apa kek, yang penting sandang pangan lebih tercukupi. Tentu, itu tidak serta merta. Hutang di terima,.. ngalir sampai ke pelosok-pelosok, itu perlu waktu. Dan juga untuk mulai terasa 'multiplier effect'-nya secara makro, itu perlu waktu juga. -

A Comparative Study of the United States Marine Corps and The

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2005 A comparative study of the United States Marine Corps and the Imperial Japanese Army in the central Pacific aW r through the experiences of Clifton Joseph Cormier and Hiroo Onoda John Earl Domingue Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Domingue, John Earl, "A comparative study of the United States Marine Corps and the Imperial Japanese Army in the central Pacific War through the experiences of Clifton Joseph Cormier and Hiroo Onoda" (2005). LSU Master's Theses. 3182. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/3182 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF THE UNITED STATES MARINES AND THE IMPERIAL JAPANESE ARMY IN THE CENTRAL PACIFIC WAR THROUGH THE EXPERIENCES OF CLIFTON JOSEPH CORMIER AND HIROO ONODA A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Liberal Arts in The Interdepartmental Program In Liberal Arts By John E. Domingue BMEd, University of Southwestern Louisiana, 1967 MEd, University of Southwestern Louisiana, 1972 December 2005 Dedication To “Nan Nan” Bea who made this degree possible even in death. -

March 2020 Patriot News

YYY E L L O W RRR I B B O N MMM INISTRY MARCH 2020 VOLUME 12, ISSUE 3 The War is Over Colonel Steve Martin Inside this Issue: In March 1942, General Douglas whatever happens, we’ll come MacArthur was ordered out of back for you. Until then, so long as Military Terms, Abbrevia- 1 the Philippines by President Roo- you have one soldier, you are to tions, and Acronyms sevelt as the Japanese were on continue to lead him. You may The War is Over 1-4 the verge of overwhelming the have to live on coconuts. If that’s American and Filipino armies. the case, live on coconuts! Under Should You Borrow from Your 2, 4 Over the next few years, the no circumstances are you to give 401(k)? Japanese entrenched its army in up your life voluntarily.” Lt. Ono- Winter Safety Tips (part 2) 2 fortified positions across the da took these words and his mission Philippines and built up logistic assignment seriously, in fact, much CAP and COOL (Education) 3 staging areas to support defen- more seriously than his commander Did You Know: Origins of Navy sive operations. In October could have anticipated. 3 Terms (conclusion) 1944, two and a half years after General Mac- Arthur promised “I Shall Return,” Allied troops In order to conduct their operations and ade- YRM Luncheons for 2020 4 returned to liberate the Philippines. quately hide in the jungles, Lt. Onoda split his men into groups of three or four men and dis- Between October 1944 and March 1945, a vi- persed them across the island. -

Surrender of Japan 1 Surrender of Japan

Surrender of Japan 1 Surrender of Japan The surrender of Japan brought hostilities in World War II to a close. By the end of July 1945, the Imperial Japanese Navy was incapable of conducting operations and an Allied invasion of Japan was imminent. While publicly stating their intent to fight on to the bitter end, Japan's leaders at the Supreme Council for the Direction of the War (the "Big Six") were privately making entreaties to the neutral Soviet Union, to mediate peace on terms favorable to the Japanese. The Soviets, meanwhile, were preparing to attack the Japanese, in fulfillment of their promises to the Americans and the British made at the Tehran and Yalta Conferences. Japanese foreign affairs minister Mamoru Shigemitsu signs the Japanese Instrument of Surrender on board USS Missouri as General Richard K. Sutherland On August 6, the Americans dropped an watches, September 2, 1945 atomic bomb on Hiroshima. Late in the evening of August 8, in accordance with Yalta agreements but in violation of the Soviet–Japanese Neutrality Pact, the Soviet Union declared war on Japan, and soon after midnight on August 9, it invaded the Japanese puppet state of Manchukuo. Later that day the Americans dropped an atomic bomb on Nagasaki. The combined shock of these events caused Emperor Hirohito to intervene and order the Big Six to accept the terms for ending the war that the Allies had set down in the Potsdam Declaration. After several more days of behind-the-scenes negotiations and a failed coup d'état, Hirohito gave a recorded radio address to the nation on August 15. -

Military History Anniversaries 1 Thru 15 MAR

Military History Anniversaries 1 thru 15 MAR Events in History over the next 15 day period that had U.S. military involvement or impacted in some way on U.S military operations or American interests Mar 01 1781 – American Revolution: Articles of Confederation are ratified » The Articles are finally ratified. They were signed by Congress and sent to the individual states for ratification on November 15, 1777, after 16 months of debate. Bickering over land claims between Virginia and Maryland delayed final ratification for almost four more years. Maryland finally approved the Articles on March 1, 1781, affirming the Articles as the outline of the official government of the United States. The nation was guided by the Articles of Confederation until the implementation of the current U.S. Constitution in 1789. The critical distinction between the Articles of Confederation and the U.S. Constitution —the primacy of the states under the Articles—is best understood by comparing the following lines. The Articles of Confederation begin: “To all to whom these Present shall come, we the undersigned Delegates of the States” By contrast, the Constitution begins: “We the People of the United Statesdo ordain and establish this Constitution for the United States of America.” The predominance of the states under the Articles of Confederation is made even more explicit by the claims of Article II: “Each state retains its sovereignty, freedom, and independence, and every power, jurisdiction, and right, which is not by this Confederation expressly delegated to the United States, in Congress assembled.” Less than five years after the ratification of the Articles of Confederation, enough leading Americans decided that the system was inadequate to the task of governance that they peacefully overthrew their second government in just over 20 years.