Oral History Interview with James Krenov, 2004 August 12-13

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oral History Interview with Jere Osgood, 2001 September 19-October 8

Oral history interview with Jere Osgood, 2001 September 19-October 8 Funding for this interview was provided by the Nanette L. Laitman Documentation Project for Craft and Decorative Arts in America. Funding for the digital preservation of this interview was provided by a grant from the Save America's Treasures Program of the National Park Service. Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Preface The following oral history transcript is the result of a tape-recorded interview with Jere Osgood on September 19 and October 8, 2001. The interview took place in Wilton, New Hampshire, and was conducted by Donna Gold for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. This interview is part of the Nanette L. Laitman Documentation Project for Craft and Decorative Arts in America. Jere Osgood and Donna Gold have reviewed the transcript and have made corrections and emendations. The reader should bear in mind that he or she is reading a verbatim transcript of spoken, rather than written prose. Interview MS. DONNA GOLD: This is Donna Gold interviewing Jere Osgood at his home in Wilton, New Hampshire, on September 19, 2001, tape one, side one. So just tell me, you were born in Staten Island. MR. JERE OSGOOD: Staten Island, New York. MS. GOLD: And the date? MR. OSGOOD: February 7, 1936. MS. GOLD: And you were raised in Staten Island, right. MR. OSGOOD: Yeah. MS. GOLD: I was wondering whether you felt that you had the -- well, did you go into Manhattan frequently? MR. -

List of 659 Books Owned by Our Department Library, As of January 2005, Listed by Subject Category

Palomar College Cabinet & Furniture Technology This is a list of 659 books owned by our Department Library, as of January 2005, listed by subject category. Our library is a reference library not a lending library. Books or Magazines must NOT be removed from the library. Our library is located between T16 and T17 classrooms, not in the campus library. Our library is open to enrolled students during all class hours. Books are located on the shelves in broad general categories, from top left to bottom right. You must return books to the correct place on the shelf after use. Books are not located under the Dewey Decimal System. The Location column in this table indicates whether the book is located on the library shelves: (S) or in reserve: (R), or Lost (N). Book Title Book Author Location Architecture Handcrafted Doors & Windows Amy Zaffarano Rowland S Japanese Detail Architecture Sadao Hibi S English Historic Carpentry Cecil A. Hewett S Vacation Homes Home Planners, Inc. S Two Story Homes Home Planners, Inc. S A Guide to the Work of Greene and Greene Randell L. Makinson S The George White & Anna Gunn Marston House S Super Luxurious Custom Homes Mike Tecton S One Story Homes Under 2000 Sq. Ft. Home Planners, Inc. S One Story Homes Over 2000 Sq. Ft. Home Planners, Inc. S One & One Half Story Homes Home Planners, Inc. S Make Your Own Handcrafted Doors & Windows John Birchard S French Interiors and Furniture Period of Louis XIV Francis J. Geck S French Interiors and Furniture Period of Louis XIII Francis J. -

Ontario Crafts Council Periodical Listing Compiled By: Caoimhe Morgan-Feir and Amy C

OCC Periodical Listing Compiled by: Caoimhe Morgan-Feir Amy C. Wallace Ontario Crafts Council Periodical Listing Compiled by: Caoimhe Morgan-Feir and Amy C. Wallace Compiled in: June to August 2010 Last Updated: 17-Aug-10 Periodical Year Season Vo. No. Article Title Author Last Author First Pages Keywords Abstract Craftsman 1976 April 1 1 In Celebration of pp. 1-10 Official opening, OCC headquarters, This article is a series of photographs and the Ontario Crafts Crossroads, Joan Chalmers, Thoma Ewen, blurbs detailing the official opening of the Council Tamara Jaworska, Dora de Pedery, Judith OCC, the Crossroads exhibition, and some Almond-Best, Stan Wellington, David behind the scenes with the Council. Reid, Karl Schantz, Sandra Dunn. Craftsman 1976 April 1 1 Hi Fibres '76 p. 12 Exhibition, sculptural works, textile forms, This article details Hi Fibres '76, an OCC Gallery, Deirdre Spencer, Handcraft exhibition of sculptural works and textile House, Lynda Gammon, Madeleine forms in the gallery of the Ontario Crafts Chisholm, Charlotte Trende, Setsuko Council throughout February. Piroche, Bob Polinsky, Evelyn Roth, Charlotte Schneider, Phyllis gerhardt, Dianne Jillings, Joyce Cosgrove, Sue Proom, Margery Powel, Miriam McCarrell, Robert Held. Craftsman 1976 April 1 2 Communications pp. 1-6 First conference, structures and This article discusses the initial Weekend programs, Alan Gregson, delegates. conference of the OCC, in which the structure of the organization, the programs, and the affiliates benefits were discussed. Page 1 of 153 OCC Periodical Listing Compiled by: Caoimhe Morgan-Feir Amy C. Wallace Periodical Year Season Vo. No. Article Title Author Last Author First Pages Keywords Abstract Craftsman 1976 April 1 2 The Affiliates of pp. -

Looking Back 40 Years, Thousands of Authors

looking back 40 years, thousands of authors ight from the start, when Paul Roman assembled the first issue of the magazine in his attic in 1975, Fine Woodworking has operated more like an academic journal than a typical magazine. RInstead of having journalists write about woodworkers and what they build, we’ve had the woodworkers themselves explaining how they work. Our editors have helped with the writing—and we take the photos—but the ideas, techniques, and designs have come directly from the authors. Their hard-won and generously shared knowledge has been the strength of the magazine for 40 years. Our contributors have run the gamut from the deeply trained to the entirely self-taught, from machine mavens to hand-tool junkies, from period- reproduction absolutists to makers whose furniture verges on sculpture. Putting a premium on personal expertise, we’ve welcomed all those points of view, often presenting directly opposing approaches to the same problem. In this final installment of Looking Back, we’ve gathered photos that represent the rich array of opinions and techniques embraced by our authors. We’ve also lined up a sampling of contributors on this page. How many do you recognize? To see if you can name them all, go to FineWoodworking.com/extras. 78 FINE WOODWORKING COPYRIGHT 2016 by The Taunton Press, Inc. Copying and distribution of this article is not permitted. The best way to cut dovetails TAILS FIRST, OR PINS? BY HAND OR MACHINE? You can find dovetails right in Fine Woodworking’s logo, and there’s doubtless been some mention of Diverse takes on the dovetail. -

Wood Threads 1977, When a Man's Fancy Tumsto Fancv

Spring $2.50 Wood Threads 1977, When a man's fancy tumsto fancv. There comes a time in every Not to mention more than 170 man's life when he outgrows the bits and cutters to pick from. Or a basic power tools. When his imagi $49.99* toter kit complete with the nation calls for more. 4600 router, wrenches, edge guide, That's the perfect time for a the three bits you'll probably use the router. One of the few power tools most, and a carrying case to hold around with hardly any limitation everything. but your imagination. All in all, it's one whale of a bar Meaning you can make flutes, gain. Especially when you consider beads, reeds, rounded comers, the one feature you can't get or almost any other finishing touch anywhere else. under the sun. Plus a lot of really Rockwell engineering. practical things, like dovetails for The kind that only comes with drawers, dadoes for shelves, rabbets half a century of indus for joints, etc., etc. trial experience and on What's more, it's all pos the-job performance. for just $39.99; the pri It goes into every of a Rockwell 4600 portable and Ij2-hp Router. For some stationary tool very good reasons. aD�.. ;_ we make. Super high speed It's why (28,000 rpm), to cut fast they're all and smooth. Microm made tough, eter depth con accurate and trol to powerful. ' adjust when you're ments ready toSo let your imagi easy. Non nation go, they'll make mamng the going good. -

New Zealand Crafts Issue 23 Autumn 1988

CRAFTS COUNCIL OF NEW ZEALAND (INC) 22 The Terrace Wellington OELU ZEHLHOD Phone: 727-018 1987/88 EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE PRESIDENT: The Crafts Cannril afNeu' Zealand John Scott (Int) is no! responsiblefin' statements 101 Putiki Drive WANGANUI and opinions published in NZ Ci'tgfis 064-50997 W nor do they m'ressin'ily relief! the Editorial 064—56921 H I’lt’II’S ofthe (Int/ix Comn‘il. Crafts Council Magazine No 23 Autumn 1988 VICE “Craft has ceased (however), to be mere decoration, and PRESIDENTS: the Anne Field craftsman has become the rival ofthe fine artist. Craft 37 Rhodes Street objects increasingly tend to be used in precisely the same CHRISTCHURCH way as paintings and scul ture in domestic and other 03-799-553 interiors — as space modulhtors and as activators of Melanie Cooper Introduction by Elizabeth Evans particular environments. ” 17 Stowe Hill So writes Edward Lucie-Smith, one of the world’s finest Thorndon WELLINGTON Craft Design Courses: the Lead-up 04734-887 writers on Art in his introduction to the inaugural by Ray Thorburn and Gavin Wilson exhibltlon at the American Craft Museum in New York. EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE: Exciting words, and having visited the museum at the Jenny Barraud An emerging Divers1ty 10 Richardson Street NELSON After two years. Craft Design courses around time ofits opening I can appreciate the sentiments 05484-619 expressed. One was given the clear impression that craft the country are developing their own hall—marks and art are inseparable, and that craft provided a greater James E. Bowman by Jenny Pattl'ir'k 103 Major Drive ran e of opportunities for artistic expression than the Kelson WELLINGTON Fientje Allis Van Rossum — a tutor profile by Eric Flegg traditional “fine arts”. -

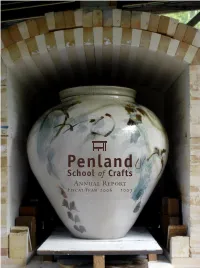

Fiscal Year 2007 Annual Report (PDF)

Penland School of Crafts Annual Report Fiscal Year 2006 – 2007 Penland’s Mission The mission of Penland School of Crafts is to support individual and artistic growth through craft. The Penland Vision Penland’s programs engage the human spirit which is expressed throughout the world in craft. Penland enriches lives by teaching skills, ideas, and the value of the handmade. Penland welcomes everyone—from vocational and avocational craft practitioners to interested visitors. Penland is a stimulating, transformative, egalitarian place where people love to work, feel free to experiment, and often exceed their own expectations. Penland’s beautiful location and historic campus inform every aspect of its work. Penland’s Educational Philosophy Penland’s educational philosophy is based on these core ideas: • Total immersion workshop education is a uniquely effective way of learning. • Close interaction with others promotes the exchange of information and ideas between individuals and disciplines. • Generosity enhances education—Penland encourages instructors, students, and staff to freely share their knowledge and experience. • Craft is kept vital by preserving its traditions and constantly expanding its boundaries. Cover Information Front cover: this pot was built by David Steumpfle during his summer workshop. It was glazed and fired by Cynthia Bringle in and sold in the Penland benefit auction for a record price. It is shown in Cynthia’s kiln at her studio at Penland. Inside front cover: chalkboard in the Pines dining room, drawing by instructor Arthur González. Inside back cover: throwing a pot in the clay studio during a workshop taught by Jason Walker. Title page: Instructors Meg Peterson and Mark Angus playing accordion duets during an outdoor Empty Bowls dinner. -

Oral History Interview with Jere Osgood

Oral history interview with Jere Osgood Funding for this interview was provided by the Nanette L. Laitman Documentation Project for Craft and Decorative Arts in America. Funding for the digital preservation of this interview was provided by a grant from the Save America's Treasures Program of the National Park Service. Archives of American Art 750 9th Street, NW Victor Building, Suite 2200 Washington, D.C. 20001 https://www.aaa.si.edu/services/questions https://www.aaa.si.edu/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 General............................................................................................................................. 2 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 1 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 2 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 2 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 1 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 2 Container Listing ..................................................................................................... -

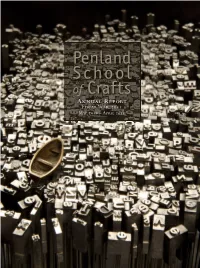

Fiscal Year 2011 Annual Report (PDF)

Penland School of Cra fts Annual Report Fiscal Year 2011 May – April Penland School of Crafts Penland School of Crafts is a national center for craft education located in North Carolina’s Blue Ridge Mountains. Penland’s focus on excel - lence, its long history, and its inspiring retreat setting have made it a model of experiential education. The school offers workshops in books and paper, clay, drawing and painting, glass, iron, metals, photography, printmaking and letterpress, textiles, wood, and other media. Penland sponsors artist residencies, a gallery and visitors center, and community education programs. Penland School of Crafts is a nonprofit, tax-exempt institution. Penland’s Mission The mission of Penland School of Crafts is to support individual and artistic growth through craft. The Penland Vision Penland is committed to providing educational programs in a total-immersion environment that nurtures individual creativity. Penland’s programs embrace traditional and contemporary approaches that respect materials and techniques while encouraging conceptual explo - ration and aesthetic innovation. Cover Information Front cover: Adrift (detail), recycled letterpress type, wire, fabricated steel, cast bronze; this piece, by core fellow Jessica Heikes, was part of The Core Show 2010 at the Penland Gallery. To see more of Jessica’s work, visit jessicaheikes.com. Back cover: Student Eli Corbin working on a monotype in the print studio. Inside front cover: The Penland auction tent during Friday night of the Annual Benefit Auction. Inside back cover: Student Ben Grant using a lathe in the wood studio. Annual Report Credits Editor: Robin Dreyer; design: Leslie Noell; writing: Robin Dreyer, Jean McLaughlin, Wes Stitt; assistance: Kate Boyd, Mike Davis, Stephanie Guinan, Tammy Hitchcock, Polly Lórien, Nancy Kerr, Susan McDaniel, Jean McLaughlin, Jennifer Sword, Wes Stitt; photographs: Robin Dreyer, except where noted. -

7 from Describing It As an Aesthetic Rejection of Modernism Or A

7 from describing it as an aesthetic rejection of modernism or a disbelief in “modern myths of progress and mastery” to a matter of the “politics of interpretation.”26 Given the varied understandings of postmodernism, it becomes necessary to outline a somewhat arbitrary definition for postmodernism in the context of studio furniture. Literally, it means that which came after the modern. Yet, because literature, film, art and architecture each found different ways of expressing modernity and its anxieties and celebrations, the various responses also took a range of forms. At the same time, some characteristics and ideas of modernism and postmodernism carry across different fields and offer a useful understanding for this discussion. The Utopian project of modernism strove to create a better, more peaceful world; poet Ezra Pound’s proclamation “make it new” offered one solution. Architects and designers turned to a stripped down modern style, the austerity of which privileged no one nation or culture over another and avoided referencing the past.27 With the desire to make new artistic creations unrelated to the past came a push for originality. In modern art, artists adhered to an idea of autonomy—that a painting or sculpture could stand alone, “existing without reference to or influence from anything else.”28 In painting and sculpture this involved abstraction and focusing on and emphasizing the particular essential qualities that make a painting a painting—its two-dimensionality, or flatness— and a sculpture a sculpture—its three-dimensionality, or form. In architecture and design, this formalism and desire for purity manifested in a focus on function. -

Plale 9: Mark Thompson (See Page 99) Buy Australian Maid. High Fired Clay with Enamels and Lustres

Plale 9: Mark Thompson (see page 99) Buy Australian Maid. high fired clay with enamels and lustres. porcelam flowers. sterling silver wires and kangaroo. braid and velvet. handbuilt in Adelaide in 1977. (h. 65cm) With a background in palDtiDg as well as ceramics. and an IDteresllD stage design. Mark Thompson (b1949) was among the firsllo successfully work from other ceramic Iraditions. He drew on lbe example of porcelain dolls. Meissen figurines and the angels. cherubs and Madonnas of the Italian Renaissance. 10 make political and sociAl satires. Olber tllies reflect his interests. FttishIVolivt Object for th. Killgoro). Pea,,'" commenled on lbe Queensland premier in 1977; Tile Martyrdom of Christopher Ihe Unwise in 1980. with nine circles of naked buuocks. !,,{erred 10 the management of the Adelaide Festival Chapter 3: The crafts as art: a shift in ideology, 1960s and 1970s This chapter will look at the ways in which the contemporary crafts movement in Australia responded to social changes, and to both contemporary art and design in the I960s and I970s. It will show the development within the movement of different ideas about what the crafts and crafts practice might be, andfocus on those who began to pursue the ideal of 'craft as art'. It will identify the main source of the change in ideals as the organised international crafts network centred particularly in the United States, and will discuss the ways in which some practitioners sought to pursue art ideals, in the context of changing values in the art world itself. Introduction The crafts movement's pursuit of art ideals was not a sudden phenomenon; nor was it something that replaced other ideals completely. -

James Gros See Page 2

era Publi calton of the American Crafts Council James Gros See page 2 Second Class Postage Paid at New York, NY and at Additional Mailing Office . ... - ".-.- . _. _._.- ._-_._--_._._----_._-------- CRAFT WORLD of Craft Horizons ACC NEWS Vol. XXXVIII No.4 Rose Slivka, Safari Off Editor-in-Chief Patricia Dandignac , OPEN to Africa Managing Editor Michael Lauretano, DOOR Fertility dolls and ceremonial Art Director Samuel Scherr masks, metalsmithing and pot Edith Dugmore, tery-these are some highlights Assistant Editor As of the April issue, you may of "The Art and Tradition of Michael McTwigan, have noticed that I revised the Editorial Assistant West Africa," a three-week tour heading of this column from of Senegal, Ghana, Togo, and Ni Isa bella Brandt, " Open Windows" to " Open Editorial Assistant geria (August 2-27, 1978, and Door," since I felt strongly that Anita Chmiel, January 7-31,1979). Sponsored Advertising Department the ncw and proper direction of by ACC and Art Safari, Inc., the the American Crafts Council tour is led by Art Safari codirec Editorial Board should invite an easy access to Junius Bird tor James Gross and fiber artist Jean Delius Arline Fi sc h the flow of information and ideas, Eleanor Dickinson. For the Au Persis Grayson not only within the U.S. but also gust tour contact, posthaste: 1924-1978 Robert Beverly Hale abroad. An open door is an invi Steven Adler, 800-223-0694, toll Lee Hall tation to exchange and growth. frce; or write ACC/ Art Safari. Pol ly Lada-Mocarski Another equally significant Jean Delius, jcweler and associate Harvey Littleton change is this month's CRAFT professor at New York State Col Ben Ra eburn HORIZONS with its section of lege at Oswego, died suddenly Ed Rossbach CRAFT WORLD.