University of Pennsylvania Press

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

0 It Comes from the Outside

How valid are visions? 0 They happen to an individual person 0 It comes from the outside 0 It isn't usually looked for by the person receiving it 0 A vision is startling and memorable 0 The "receiver" will want to tell others about it 0 Visions are hard to put into words 0 They only have meaning if they convey a deeper message 0 Visions could be the result of an overactive imagination - or drug or alcohol induced Find an example of a religious vision and explain what the vision was and why it is important Assessment question. "Visions are only important for the person who receives them." Do you agree? Give reasons for your answer, showing that you have thought about more than one point of view. I 25 Dreams are a series of thoughts, images and sensations occurring in a person's mind during sleep. Many people forget their dreams. However there are some dreams which can make a deep impression on the person dreaming and, as with visions, they might give the dreamer new insights into reality and into God. Such dreams can give new direction to a person's life. For these dreams to be valid, they have to be free from any artificial stimulus, e.g. drugs! You are going to research 2 dreams and explain their meaning by answering the following questions: hlow valid are dreams? Name of Jacob's dream at Bethel Pharaoh's dream the dream Explain this dream How did God use this dream What affect did it have on the person 26 0 Dreams happen when a person is asleep 0 Most people forget their dreams but some leave a deep impression 0 Dreams might give new insights into reality and into God 0 People don't have control over their dreams 0 For dreams to be valid they have to be free from artificial stimulus Special Revelation: Enlightenment! Obiectives: Understand how enlightenment can help a believer deal with life and its pressures Evaluate the importance of enlightenment for believers and their faith ^ Task 1: Enlightenment is. -

Network Map of Knowledge And

Humphry Davy George Grosz Patrick Galvin August Wilhelm von Hofmann Mervyn Gotsman Peter Blake Willa Cather Norman Vincent Peale Hans Holbein the Elder David Bomberg Hans Lewy Mark Ryden Juan Gris Ian Stevenson Charles Coleman (English painter) Mauritz de Haas David Drake Donald E. Westlake John Morton Blum Yehuda Amichai Stephen Smale Bernd and Hilla Becher Vitsentzos Kornaros Maxfield Parrish L. Sprague de Camp Derek Jarman Baron Carl von Rokitansky John LaFarge Richard Francis Burton Jamie Hewlett George Sterling Sergei Winogradsky Federico Halbherr Jean-Léon Gérôme William M. Bass Roy Lichtenstein Jacob Isaakszoon van Ruisdael Tony Cliff Julia Margaret Cameron Arnold Sommerfeld Adrian Willaert Olga Arsenievna Oleinik LeMoine Fitzgerald Christian Krohg Wilfred Thesiger Jean-Joseph Benjamin-Constant Eva Hesse `Abd Allah ibn `Abbas Him Mark Lai Clark Ashton Smith Clint Eastwood Therkel Mathiassen Bettie Page Frank DuMond Peter Whittle Salvador Espriu Gaetano Fichera William Cubley Jean Tinguely Amado Nervo Sarat Chandra Chattopadhyay Ferdinand Hodler Françoise Sagan Dave Meltzer Anton Julius Carlson Bela Cikoš Sesija John Cleese Kan Nyunt Charlotte Lamb Benjamin Silliman Howard Hendricks Jim Russell (cartoonist) Kate Chopin Gary Becker Harvey Kurtzman Michel Tapié John C. Maxwell Stan Pitt Henry Lawson Gustave Boulanger Wayne Shorter Irshad Kamil Joseph Greenberg Dungeons & Dragons Serbian epic poetry Adrian Ludwig Richter Eliseu Visconti Albert Maignan Syed Nazeer Husain Hakushu Kitahara Lim Cheng Hoe David Brin Bernard Ogilvie Dodge Star Wars Karel Capek Hudson River School Alfred Hitchcock Vladimir Colin Robert Kroetsch Shah Abdul Latif Bhittai Stephen Sondheim Robert Ludlum Frank Frazetta Walter Tevis Sax Rohmer Rafael Sabatini Ralph Nader Manon Gropius Aristide Maillol Ed Roth Jonathan Dordick Abdur Razzaq (Professor) John W. -

'The Supreme Principle of Morality'? in the Preface to His Best

The Supreme Principle of Morality Allen W. Wood 1. What is ‘The Supreme Principle of Morality’? In the Preface to his best known work on moral philosophy, Kant states his purpose very clearly and succinctly: “The present groundwork is, however, nothing more than the search for and establishment of the supreme principle of morality, which already constitutes an enterprise whole in its aim and to be separated from every other moral investigation” (Groundwork 4:392). This paper will deal with the outcome of the first part of this task, namely, Kant’s attempt to formulate the supreme principle of morality, which is the intended outcome of the search. It will consider this formulation in light of Kant’s conception of the historical antecedents of his attempt. Our first task, however, must be to say a little about the meaning of the term ‘supreme principle of morality’. For it is not nearly as evident to many as it was to Kant that there is such a thing at all. And it is extremely common for people, whatever position they may take on this issue, to misunderstand what a ‘supreme principle of morality’ is, what it is for, and what role it is supposed to play in moral theorizing and moral reasoning. Kant never directly presents any argument that there must be such a principle, but he does articulate several considerations that would seem to justify supposing that there is. Kant holds that moral questions are to be decided by reason. Reason, according to Kant, always seeks unity under principles, and ultimately, systematic unity under the fewest possible number of principles (Pure Reason A298-302/B355-359, A645- 650/B673-678). -

Coversheet for Thesis in Sussex Research Online

A University of Sussex PhD thesis Available online via Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/ This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Please visit Sussex Research Online for more information and further details ‘Providence and Political Economy’: Josiah Tucker’s Providential Argument for Free Trade Peter Xavier Price PhD Thesis in Intellectual History University of Sussex April 2016 2 University of Sussex Peter Xavier Price Submitted for the award of a PhD in Intellectual History ‘Providence and Political Economy’: Josiah Tucker’s Providential Argument for Free Trade Thesis Summary Josiah Tucker, who was the Anglican Dean of Gloucester from 1758 until his death in 1799, is best known as a political pamphleteer, controversialist and political economist. Regularly called upon by Britain’s leading statesmen, and most significantly the Younger Pitt, to advise them on the best course of British economic development, in a large variety of writings he speculated on the consequences of North American independence for the global economy and for international relations; upon the complicated relations between small and large states; and on the related issue of whether low wage costs in poor countries might always erode the competitive advantage of richer nations, thereby establishing perpetual cycles of rise and decline. -

Summary the Purpose of the Dissertation Is to Present The

Summary The purpose of the dissertation is to present the abductive argument of Richard Swinburne in favor of theism. Richard Swinburne was born on December 26, 1934. He is a British philosopher, a retired professor of the University of Oxford, where he held the position of Nolloth Professor of the Philosophy of the Christian Religion (Oriel College). He has devoted all his philosophical activity to the justification of the Christian faith – he has intended to show that it is rational to believe in God. The main thesis of the dissertation is that Swinburne’s concept of theism does not remain consistent with the assumption that God is perfectly good. This inconsistence comes from the fact that human experience of suffering cannot be reconciled with God’s perfect goodness, especially assuming that God allows or causes the suffering. The structure of the work corresponds to the logical construction of Swinburne’s line of reasoning. The first chapter – Methodology of Philosophy – describes the main philosophical methods Swinburne uses in presenting his arguments. It is divided into two parts: the first one (Theory of Explanation) primarily presents the Swinburne’s construction of the concept of coherence, which is a prerequisite for considering any theory as probable or true. Moreover, this part discusses Swinburne’s dual explanatory theory, according to which two types of explanation are possible: (1) scientific, based on the analysis of unintentional causation, and (2) personal, based on the analysis of intentional causation. At the same time, Swinburne tries to show that it is not possible to explain certain phenomena in the world only by means of scientific explanation. -

The Argument from Miracles: a Cumulative Case for the Resurrection of Jesus of Nazareth

The Argument from Miracles: A Cumulative Case for the Resurrection of Jesus of Nazareth Introduction It is a curiosity of the history of ideas that the argument from miracles is today better known as the object of a famous attack than as a piece of reasoning in its own right. It was not always so. From Paul’s defense before Agrippa to the polemics of the orthodox against the deists at the heart of the Enlightenment, the argument from miracles was central to the discussion of the reasonableness of Christian belief, often supplemented by other considerations but rarely omitted by any responsible writer. But in the contemporary literature on the philosophy of religion it is not at all uncommon to find entire works that mention the positive argument from miracles only in passing or ignore it altogether. Part of the explanation for this dramatic change in emphasis is a shift that has taken place in the conception of philosophy and, in consequence, in the conception of the project of natural theology. What makes an argument distinctively philosophical under the new rubric is that it is substantially a priori, relying at most on facts that are common knowledge. This is not to say that such arguments must be crude. The level of technical sophistication required to work through some contemporary versions of the cosmological and teleological arguments is daunting. But their factual premises are not numerous and are often commonplaces that an educated nonspecialist can readily grasp – that something exists, that the universe had a beginning in time, that life as we know it could flourish only in an environment very much like our own, that some things that are not human artifacts have an appearance of having been designed. -

Cotton Mather's Relationship to Science

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University English Theses Department of English 4-16-2008 Cotton Mather's Relationship to Science James Daniel Hudson Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_theses Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Hudson, James Daniel, "Cotton Mather's Relationship to Science." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2008. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_theses/33 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of English at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COTTON MATHER’S RELATIONSHIP TO SCIENCE by JAMES DANIEL HUDSON Under the Direction of Dr. Reiner Smolinski ABSTRACT The subject of this project is Cotton Mather’s relationship to science. As a minister, Mather’s desire to harmonize science with religion is an excellent medium for understanding the effects of the early Enlightenment upon traditional views of Scripture. Through “Biblia Americana” and The Christian Philosopher, I evaluate Mather’s effort to relate Newtonian science to the six creative days as recorded in Genesis 1. Chapter One evaluates Mather’s support for the scientific theories of Isaac Newton and his reception to natural philosophers who advocate Newton’s theories. Chapter Two highlights Mather’s treatment of the dominant cosmogonies preceding Isaac Newton. The Conclusion returns the reader to Mather’s principal occupation as a minister and the limits of science as informed by his theological mind. Through an exploration of Cotton Mather’s views on science, a more comprehensive understanding of this significant early American and the ideological assumptions shaping his place in American history is realized. -

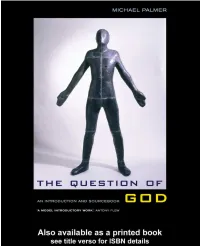

THE QUESTION of GOD: an Introduction and Sourcebook

THE QUESTION OF GOD This important new text by a well-known author provides a lively and approachable introduction to the six great arguments for the existence of God. Requiring no specialist knowledge of philosophy, an important feature of The Question of God is the inclusion of a wealth of primary sources drawn from both classic and contemporary texts. With its combination of critical analysis and extensive extracts, this book will be particularly attractive to students and teachers of philosophy, religious studies and theology, at school or university level, who are looking for a text that offers a detailed and authoritative account of these famous arguments. • The Ontological Argument (sources: Anselm, Haight, Descartes, Kant, Findlay, Malcolm, Hick) • The Cosmological Argument (sources: Aquinas, Taylor, Hume, Kant) • The Argument from Design (sources: Paley, Hume, Darwin, Dawkins, Ward) • The Argument from Miracles (sources: Hume, Hambourger, Coleman, Flew, Swinburne, Diamond) • The Moral Argument (sources: Plato, Lewis, Kant, Rachels, Martin, Nielsen) • The Pragmatic Argument (sources: Pascal, Gracely, Stich, Penelhum, James, Moore). This user-friendly books also offers: • Revision questions to aid comprehension • Key reading for each chapter and an extensive bibliography • Illustrated biographies of key thinkers and their works • Marginal notes and summaries of arguments. Dr Michael Palmer was formerly a Teaching Fellow at McMaster University and Humbodlt Fellow at Marburg University. He has also taught at Marlborough College and Bristol University, and was for many years Head of the Department of Religion and Philosophy at The Manchester Grammar School. A widely read author, his Moral Problems (1991) has already established itself as a core text in schools and colleges. -

Of Gods and Kings: Natural Philosophy and Politics in the Leibniz-Clarke Disputes Steven Shapin Isis, Vol. 72, No. 2. (Jun., 1981), Pp

Of Gods and Kings: Natural Philosophy and Politics in the Leibniz-Clarke Disputes Steven Shapin Isis, Vol. 72, No. 2. (Jun., 1981), pp. 187-215. Stable URL: http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0021-1753%28198106%2972%3A2%3C187%3AOGAKNP%3E2.0.CO%3B2-C Isis is currently published by The University of Chicago Press. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/about/terms.html. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/journals/ucpress.html. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. The JSTOR Archive is a trusted digital repository providing for long-term preservation and access to leading academic journals and scholarly literature from around the world. The Archive is supported by libraries, scholarly societies, publishers, and foundations. It is an initiative of JSTOR, a not-for-profit organization with a mission to help the scholarly community take advantage of advances in technology. For more information regarding JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. http://www.jstor.org Mon Aug 20 10:29:37 2007 Of Gods and Kings: Natural Philosophy and Politics in the Leibniz-Clarke Disputes By Steven Shapin* FTER TWO AND A HALF CENTURIES the Newton-Leibniz disputes A continue to inflame the passions. -

An Analysis of Hume's Arguments Concerning the Role of Reason In

This dissertation has been 64—1244 microfilmed exactly as received BROILES, Rowland David, 1938- AN ANALYSIS OF HUME'S ARGUMENTS CONCERN ING THE ROLE OF REASON IN MORAL DECISIONS. The Ohio State University, Ph.D., 1963 P h ilosop h y University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan IN ANALYSIS OF HUME'S ARGUMENTS CONCERNING THE ROLE OF REASON IN MORAL DECISIONS DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of the Ohio State University By Rowland David Broiles, B.A., M.A The Ohio State University 1963 Approved by ' idvisor Department of Philosophy CONTENTS Chapter Page I. INTRODUCTION .................................. I II. HUME'S PREDECESSORS............................ 11 III. REASON AND PASSIONS .......................... ^0 IV.‘ EXCITING AND JUSTIFYING REASONS......... 81 V. HUME'S CRITIQUE OF THE RATIONALISTS............. 1112 VI. THE "IS-OUGHT" PASSAGE........................ 133 BIBLIOGRAPHY............ 1^9 AUTOBIOGRAPHY ......................................... 15^ 11 CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION In the history of philosophy it has sometimes been the case that a philosopher has been considered to be important primarily because of the relationship he bears to some apparently greater philosopher* It was the plight of David Hume, until only recently, to have been so regarded* For Hume0s importance as a philosopher was considered to lie not so much in his own philosophical doctrines, but in the effect they had on Kant, and by this means on the subsequent character -

Caroline, Leibniz, and Clarke Author(S): D. Bertoloni Meli Source: Journal of the History of Ideas, Vol

Caroline, Leibniz, and Clarke Author(s): D. Bertoloni Meli Source: Journal of the History of Ideas, Vol. 60, No. 3 (Jul., 1999), pp. 469-486 Published by: University of Pennsylvania Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3654014 . Accessed: 22/02/2011 14:57 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at . http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=upenn. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. University of Pennsylvania Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Journal of the History of Ideas. http://www.jstor.org Caroline, Leibniz, and Clarke D. Bertoloni Meli The papers which passed between Leibniz and Clarke from 1715 to 1716 have long been considered classics in the history of science and philosophy, attractinga largenumber of scholarlyworks. -

The Leibnizian-Newtonian Debates: Natural Philosophy and Social Psychology

The British Society for the History of Science !"#$%#&'(&)&*(+,#-./(&*($0#'*.#12$,*.34*5$6"&5/1/7"8$*(9$:/;&*5$618;"/5/<8 =3."/4>1?2$@*4/58($A5.&1 :/34;#2$!"#$B4&.&1"$C/34(*5$D/4$."#$E&1./48$/D$:;&#(;#F$G/5H$IF$,/H$J$>0#;HF$KLMN?F$77H$NJN+NMM 63'5&1"#9$'82$@*O'4&9<#$P(&Q#41&.8$64#11$/($'#"*5D$/D$!"#$B4&.&1"$:/;&#.8$D/4$."#$E&1./48 /D$:;&#(;# :.*'5#$PR%2$http://www.jstor.org/stable/4025501 =;;#11#92$KSTUITVUKU$VV2WS Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=cup. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship.