Identity, Protest, and Outreach in the Arts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Black Arts Enterprise and the Production of African American Poetry

0/-*/&4637&: *ODPMMBCPSBUJPOXJUI6OHMVFJU XFIBWFTFUVQBTVSWFZ POMZUFORVFTUJPOT UP MFBSONPSFBCPVUIPXPQFOBDDFTTFCPPLTBSFEJTDPWFSFEBOEVTFE 8FSFBMMZWBMVFZPVSQBSUJDJQBUJPOQMFBTFUBLFQBSU $-*$,)&3& "OFMFDUSPOJDWFSTJPOPGUIJTCPPLJTGSFFMZBWBJMBCMF UIBOLTUP UIFTVQQPSUPGMJCSBSJFTXPSLJOHXJUI,OPXMFEHF6OMBUDIFE ,6JTBDPMMBCPSBUJWFJOJUJBUJWFEFTJHOFEUPNBLFIJHIRVBMJUZ CPPLT0QFO"DDFTTGPSUIFQVCMJDHPPE The Black Arts Enterprise and the Production of African American Poetry The Black Arts Enterprise and the Production of African American Poetry Howard Rambsy II The University of Michigan Press • Ann Arbor First paperback edition 2013 Copyright © by the University of Michigan 2011 All rights reserved Published in the United States of America by The University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America c Printed on acid-free paper 2016 2015 2014 2013 5432 No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, or otherwise, without the written permission of the publisher. A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Rambsy, Howard. The black arts enterprise and the production of African American poetry / Howard Rambsy, II. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-472-11733-8 (cloth : acid-free paper) 1. American poetry—African American authors—History and criticism. 2. Poetry—Publishing—United States—History—20th century. 3. African Americans—Intellectual life—20th century. 4. African Americans in literature. I. Title. PS310.N4R35 2011 811'.509896073—dc22 2010043190 ISBN 978-0-472-03568-7 (pbk. : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-472-12005-5 (e-book) Cover illustrations: photos of writers (1) Haki Madhubuti and (2) Askia M. Touré, Mari Evans, and Kalamu ya Salaam by Eugene B. Redmond; other images from Shutterstock.com: jazz player by Ian Tragen; African mask by Michael Wesemann; fist by Brad Collett. -

Finding Aid to the Historymakers ® Video Oral History with Naomi Long Madgett

Finding Aid to The HistoryMakers ® Video Oral History with Naomi Long Madgett Overview of the Collection Repository: The HistoryMakers®1900 S. Michigan Avenue Chicago, Illinois 60616 [email protected] www.thehistorymakers.com Creator: Madgett, Naomi Cornelia Long. Title: The HistoryMakers® Video Oral History Interview with Naomi Long Madgett, Dates: June 27, 2007 and March 5, 2007 Bulk Dates: 2007 Physical 12 Betacame SP videocasettes (5:29:45). Description: Abstract: Poet and english professor Naomi Long Madgett (1923 - ) was first published at age twelve. Madgett was the recipient of many honors including 1993's American Book Award and the George Kent Award in 1995. Madgett was interviewed by The HistoryMakers® on June 27, 2007 and March 5, 2007, in Detriot, Michigan and Detroit, Michigan. This collection is comprised of the original video footage of the interview. Identification: A2007_072 Language: The interview and records are in English. Biographical Note by The HistoryMakers® Poet and English professor emeritus Naomi Cornelia Long Madgett was born on July 5, 1923 in Norfolk, Virginia to the Reverend Clarence Marcellus Long and the former Maude Selena Hilton. Growing up in East Orange, New Jersey, she attended Ashland Grammar School and Bordentown School. At age twelve, Madgett’s poem, My Choice, was published on the youth page of the Orange Daily Courier. In 1937, the family moved to St. Louis, Missouri where her schoolmates included Margaret Bush Wilson, E. Sims Campbell and lifelong friend, baritone Robert McFerrin, Sr. Madgett, at age fifteen, established a friendship with Langston Hughes. Just days after graduating with honors from Charles Sumner High School in 1941, Madgett’s first book of poetry, Songs to a Phantom Nightingale was published. -

Kenneth A. Merique Genealogical and Historical Collection BOOK NO

Kenneth A. Merique Genealogical and Historical Collection SUBJECT OR SUB-HEADING OF SOURCE OF BOOK NO. DATE TITLE OF DOCUMENT DOCUMENT DOCUMENT BG no date Merique Family Documents Prayer Cards, Poem by Christopher Merique Ken Merique Family BG 10-Jan-1981 Polish Genealogical Society sets Jan 17 program Genealogical Reflections Lark Lemanski Merique Polish Daily News BG 15-Jan-1981 Merique speaks on genealogy Jan 17 2pm Explorers Room Detroit Public Library Grosse Pointe News BG 12-Feb-1981 How One Man Traced His Ancestry Kenneth Merique's mission for 23 years NE Detroiter HW Herald BG 16-Apr-1982 One the Macomb Scene Polish Queen Miss Polish Festival 1982 contest Macomb Daily BG no date Publications on Parental Responsibilities of Raising Children Responsibilities of a Sunday School E.T.T.A. BG 1976 1981 General Outline of the New Testament Rulers of Palestine during Jesus Life, Times Acts Moody Bible Inst. Chicago BG 15-29 May 1982 In Memory of Assumption Grotto Church 150th Anniversary Pilgrimage to Italy Joannes Paulus PP II BG Spring 1985 Edmund Szoka Memorial Card unknown BG no date Copy of Genesis 3.21 - 4.6 Adam Eve Cain Abel Holy Bible BG no date Copy of Genesis 4.7- 4.25 First Civilization Holy Bible BG no date Copy of Genesis 4.26 - 5.30 Family of Seth Holy Bible BG no date Copy of Genesis 5.31 - 6.14 Flood Cainites Sethites antediluvian civilization Holy Bible BG no date Copy of Genesis 9.8 - 10.2 Noah, Shem, Ham, Japheth, Ham father of Canaan Holy Bible BG no date Copy of Genesis 10.3 - 11.3 Sons of Gomer, Sons of Javan, Sons -

Bright Moments!

Volume 46 • Issue 6 JUNE 2018 Journal of the New Jersey Jazz Society Dedicated to the performance, promotion and preservation of jazz. On stage at NJPAC performing Rahsaan Roland Kirk’s “Bright Moments” to close the tribute to Dorthaan Kirk on April 28 are (from left) Steve Turre, Mark Gross, musical director Don Braden, Antoinette Montague and Freddy Cole. Photo by Tony Graves. SNEAKING INTO SAN DIEGO BRIGHT MOMENTS! Pianist Donald Vega’s long, sometimes “Dorthaan At 80” Celebrating Newark’s “First harrowing journey from war-torn Nicaragua Lady of Jazz” Dorthaan Kirk with a star-filled gala to a spot in Ron Carter’s Quintet. Schaen concert and tribute at the New Jersey Performing Arts Fox’s interview begins on page 14. Center. Story and Tony Graves’s photos on page 24. New JerseyJazzSociety in this issue: New Jersey Jazz socIety Prez Sez . 2 Bulletin Board . 2 NJJS Calendar . 3 Jazz Trivia . 4 Prez sez Editor’s Pick/Deadlines/NJJS Info . 6 Change of Address/Support NJJS/ By Cydney Halpin President, NJJS Volunteer/Join NJJs . 43 Crow’s Nest . 44 t is with great delight that I announce Don commitment to jazz, and for keeping the music New/Renewed Members . 45 IBraden has joined the NJJS Board of Directors playing. (Information: www.arborsrecords.com) in an advisory capacity. As well as being a jazz storIes n The April Social at Shanghai Jazz showcased musician of the highest caliber on saxophone and Dorthaan at 80 . cover three generations of musicians, jazz guitar Big Band in the Sky . 8 flute, Don is an award-winning recording artist, virtuosi Gene Bertoncini and Roni Ben-Hur and Memories of Bob Dorough . -

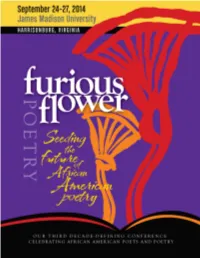

Furiousflower2014 Program.Pdf

Dedication “We are each other’s harvest; we are each other’s business; we are each other’s magnitude and bond.” • GWENDOLYN BROOKS Dedicated to the memory of these poets whose spirit lives on: Ai Margaret Walker Alexander Maya Angelou Alvin Aubert Amiri Baraka Gwendolyn Brooks Lucille Clifton Wanda Coleman Jayne Cortez June Jordan Raymond Patterson Lorenzo Thomas Sherley Anne Williams And to Rita Dove, who has sharpened love in the service of myth. “Fact is, the invention of women under siege has been to sharpen love in the service of myth. If you can’t be free, be a mystery.” • RITA DOVE Program design by RobertMottDesigns.com GALLERY OPENING AND RECEPTION • DUKE HALL Events & Exhibits Special Time collapses as Nigerian artist Wole Lagunju merges images from the Victorian era with Yoruba Gelede to create intriguing paintings, and pop culture becomes bedfellows with archetypal imagery in his kaleidoscopic works. Such genre bending speaks to the notions of identity, gender, power, and difference. It also generates conversations about multicultur- alism, globalization, and transcultural ethos. Meet the artist and view the work during the Furious Flower reception at the Duke Hall Gallery on Wednesday, September 24 at 6 p.m. The exhibit is ongoing throughout the conference, 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. FUSION: POETRY VOICED IN CHORAL SONG FORBES CENTER FOR THE PERFORMING ARTS Our opening night concert features solos by soprano Aurelia Williams and performances by the choirs of Morgan State University (Eric Conway, director) and James Madison University (Jo-Anne van der Vat-Chromy, director). In it, composer and pianist Randy Klein presents his original music based on the poetry of Margaret Walker, Michael Harper, and Yusef Komunyakaa. -

Print Version (Pdf)

Special Collections and University Archives : University Libraries Broadside Press Collection 1965-1984 (Bulk: 1965-1975) 1 box, 110 vols. (3.5 linear ft.) Call no.: MS 571 Collection overview A significant African American poet of the generation of the 1960s, Dudley Randall was an even more significant publisher of emerging African American poets and writers. Publishing works by important writers from Gwendolyn Brooks to Haki Madhubuti, Alice Walker, Etheridge Knight, Audre Lorde, Amiri Baraka, Nikki Giovanni, and Sonia Sanchez, his Broadside Press in Detroit became an important contributor to the Black Arts Movement. The Broadside Press Collection includes approximately 200 titles published by Randall's press during its first decade of operation, the period of its most profound cultural influence. The printed works are divided into five series, Broadside poets (including chapbooks, books of poetry, and posters), anthologies, children's books, the Broadside Critics Series (works of literary criticism by African American authors), and the Broadsides Series. The collection also includes a selection of items used in promoting Broadside Press publications, including a broken run of the irregularly published Broadside News, press releases, catalogs, and fliers and advertising cards. See similar SCUA collections: African American Antiracism Arts and literature Literature and language Poetry Printed materials Prose writing Social justice Background Dudley Randall was working as a librarian in Detroit in 1963 when he learned of the brutal bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama. Randall's poetic response was "The Ballad of Birmingham," a work that became widely known after it was set to music by the folk singer Jerry Moore. -

David Dichiera

DAVID DICHIERA 2013 Kresge Eminent Artist THE KRESGE EMINENT ARTIST AWARD HONORS AN EXCEPTIONAL ARTIST IN THE VISUAL, PEFORMING OR LITERARY ARTS FOR LIFELONG PROFESSIONAL ACHIEVEMENTS AND CONTRIBUTIONS TO METROPOLITAN DETROIT’S CULTURAL COMMUNITY. DAVID DICHIERA IS THE 2013 KRESGE EMINENT ARTIST. THIS MONOGRAPH COMMEMORATES HIS LIFE AND WORK. CONTENTS 3 Foreword 59 The Creation of “Margaret Garner” By Rip Rapson By Sue Levytsky President and CEO The Kresge Foundation 63 Other Voices: Tributes and Reflections 4 Artist’s Statement Betty Brooks Joanne Danto Heidi Ewing The Impresario Herman Frankel Denyce Graves 8 The Grand Vision of Bill Harris David DiChiera Kenny Leon By Sue Levytsky Naomi Long Madgett Nora Moroun 16 Timeline of a Lifetime Vivian R. Pickard Marc Scorca 18 History of Michigan Opera Theatre Bernard Uzan James G. Vella Overture to Opera Years: 1961-1971 Music Hall Years: 1972-1983 R. Jamison Williams, Jr. Fisher/Masonic Years: 1985-1995 Mayor Dave Bing Establishing a New Home: 1990-1995 Governor Rick Snyder The Detroit Opera House:1996 Senator Debbie Stabenow “Cyrano”: 2007 Senator Carol Levin Securing the Future By Timothy Paul Lentz, Ph.D. 75 Biography 24 Setting stories to song in MOTown 80 Musical Works 29 Michigan Opera Theatre Premieres Kresge Arts in Detroit 81 Our Congratulations 37 from Michelle Perron A Constellation of Stars Director, Kresge Arts in Detroit 38 The House Comes to Life: 82 A Note from Richard L. Rogers Facts and Figures President, College for Creative Studies 82 Kresge Arts in Detroit Advisory Council The Composer 41 On “Four Sonnets” 83 About the Award 47 Finding My Timing… 83 Past Eminent Artist Award Winners Opera is an extension of something that By David DiChiera is everywhere in the world – that is, 84 About The Kresge Foundation 51 Philadelphia’s “Cyranoˮ: A Review 84 The Kresge Foundation Board the combination of music and story. -

When Négritude Was in Vogue: Critical Reflections of the First World Festival of Negro Arts and Culture in 1966

When Négritude Was In Vogue: Critical Reflections of the First World Festival of Negro Arts and Culture in 1966 by Anthony J. Ratcliff, Ph.D. [email protected] Assistant Professor, Department of Pan African Studies California State University, Northridge Abstract Six years after assuming the presidency of a newly independent Senegal, Leopold Sédar Senghor, with the support of UNESCO, convened the First World Festival of Negro Arts and Culture in Dakar held from April 1-24, 1966. The Dakar Festival was Senghor’s attempt to highlight the development of his country and “his” philosophy, Négritude. Margaret Danner, a Afro-North American poet from Chicago and attendee of the Festival referred to him as “a modern African artist, as host; / a word sculpturer (sic), strong enough to amass / the vast amount of exaltation needed to tow his followers through / the Senegalese sands, toward their modern rivers and figures of gold.” For Danner and many other Black cultural workers in North America, the prospects of attending an international festival on the African continent intimated that cultural unity among Africans and Afro-descendants was rife with possibility. What is more, for a brief historical juncture, Senghor and his affiliates were able to posit Négritude as a viable philosophical model in which to realize this unity. However, upon critical reflection, a number of the Black cultural workers who initially championed the Dakar Festival came to express consternation at the behind the scenes machinations which severely weakened the “lovely dream” of “Pan-Africa.” 167 The Journal of Pan African Studies, vo.6, no.7, February 2014 Following Senegal’s independence from France in 1960, the poet-statesman Leopold Sédar Senghor became the county’s first African president. -

Diasporic Returns in the Jet Age: the First World Festival of Negro Arts and the Promise of Air Travel

DIASPORIC RETURNS IN THE JET AGE: THE FIRST WORLD FESTIVAL OF NEGRO ARTS AND THE PROMISE OF AIR TRAVEL Tobias Wofford Art History Department, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, Virginia, USA ..................The First World Festival of Negro Arts (FESMAN) was decidedly a product of African independence, reflecting cultural and political aspirations of an African diaspora emergent world order. It was also decidedly a product of the jet age. While aviation air travel seems commonplace today, the commercial jet airliner was still a novel sign of futurity in 1966. Early stages of commercial jet travel often FESMAN followed colonial routes into Africa, a postwar extension of Europe’s Greaves imperial era. FESMAN offered the opportunity to reimagine air travel for the service of the international community built around independence-era William Africa and the African diaspora. This essay examines the trope of air travel Pan-African as a vital symbol of modernity invoked by FESMAN’s organizers and festivals participants. For example, many American visitors to the festival noted both the speed with which Pan Am jets shuttled them to the once- ................. prohibitively remote continent as well as the shining international architecture of the newly built airport. The trope of air travel is perhaps most beautifully elaborated in American filmmaker William Greaves’ lyrical documentary, The First World Festival of Negro Arts. The film strategically employed the marvel of air travel and its potential as a medium for ....................................................................................................... interventions, 2018 https://doi.org/10.1080/1369801X.2018.1487799 Tobias Wofford [email protected] © 2018 Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group ............................interventions – 0:0 2 facilitating the global networks proposed by the festival. -

Robert F. Williams, Detroit, and the Bandung Era

Transnational Correspondence: Robert F. Williams, Detroit, and the Bandung Era Bill V. Mullen Can you imagine New York without police brutal- ity? Can you imagine Chicago without gangsters and Los Angeles without dirilects [sic] and winos? Can you imagine Birmingham without racial dis- crimination and Jackson, Mississippi without ter- ror? . Can you imagine cops and soldiers without firearms in conspicuous evidence of intimidation? Do you think this is a utopian dream? I can understand your disbelief. I believe that such a place exists on this wicked and cruel earth. —Robert F. Williams, “China: The Good of the Earth,” 19631 [A]ll genuine Bandung revolutionaries must unequivocally support the Revolutionary Afro- American Movement. The Black American radical is a redeemer who must resurrect a colonial peo- ple who suffered centuries of spiritual and psy- chological genocide, and who acknowledges but one history——-. slavery…. The Afro-American revolutionary is the humanistic antithesis of the inhuman West. —Revolutionary Action Movement, Black America, 19652 We learned from Detroit to go to the cities. —General Vo Nguyen Giap to Robert Williams, 19683 The September, 1963, special issue of Shijie Wenxue (World WORKS•AND•DAYS•39/40, Vol. 20, Nos. 1&2, 2002 190 WORKS•AND•DAYS Literature) published in Beijing was dedicated to W. E .B. Du Bois. The lyric poet to China, twice a visitor there, had died in August on the eve of the March on Washington. Working quickly, the editors had compiled an extraordinary gathering of writers and writings in his name. They included Du Bois’s own poem “Ghana Calls,” writ- ten to commemorate his final exile; Sie Ping-hsin’s “To Mourn for the Death of Dr. -

The Poetry of Bob Kaufman

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2005 When I Die, I Won't Stay Dead: The oP etry of Bob Kaufman Mona Lisa Saloy Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Saloy, Mona Lisa, "When I Die, I Won't Stay Dead: The oeP try of Bob Kaufman" (2005). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3400. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3400 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. WHEN I DIE, I WON’T STAY DEAD: THE POETRY OF BOB KAUFMAN A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of English by Mona Lisa Saloy B.A., University of Washington, 1979 M.A., San Francisco State University, 1981 M.F.A, Louisiana State University, 1988 August, 2005 ©Copyright 2005 Mona Lisa Saloy All rights reserves ii For my sister Barbara Ann, who encouraged my educational pursuits, and for Donald Kaufman, who though dying, helped me to know his brother. iii Acknowledgments I must thank the members of my Dissertation committee who allowed my passion to find the real Kaufman to grow, encouraged me through personal trials, and brought to my work their love of African American culture and literature as well as their trust in my pursuit. -

The Bdok Deals with Classroom Uses of Black American 10Ratue

.. an/ DOCUMENT RESUME ED 158 293 CS 204 277 AUTHOR Stanford, BarbaDa Aiin, KariLa TITLE__ 'Black Literature fot High School Students. INSTITUTION national Council of Teachers of English, Uibana, Ill. PUB 'DATE 18 NOTE 274p. '4AVAILABLE PROMNational Councilof Teachers of English, 1111 Kenyon Road, Urbana, Illinois 61801 (Stock.No..0330,6, $4.75. non-member, $3.,95 member) - ERRS' PRICE 40-$0.83 HC-$14.05 Plus'Postag,. BESCRIPTORS African Literature; American Literature; Annotated Bibliographies; Autobiographies; Biographies; *Black Culture; *Black History; *Black Literature; Black Studies"; Class Activities; EnglishInstruction; Fiction; Polk Culture; literary Influences; *Literary Perspective;,Literary Styles; *Literature Appreciation; *Literature Programs; Mythology; Secondary Education ABSTRACT . An interracial team of:teacherS'" and regional consultanti worked together_reV#insthisten-syear-old book on the _ teaching of black literature. ne first section discusses black literature in terms of its discovery, tradition, and affective aspects; outlines goals and objectives for the course; presents a historical survey of black American writers; considers junior novels, short story collections, 'biographies, and, autobiographies (historical And moitern) by bot black and white writers; an0 presents supplementary bibliographies. of.black literature. The second part of .the bdok deals with classroom uses of black American 10ratUe. Included in" this section-are outlines for two literature 'units on the bla6k experience; units on slave narratives and autobiography, poetry), and the short story; ecouise onAfro-American literature; _and a senior elective course on black literature, for which a bibliography is included. Also included are suggestions for bomposition, discussion, role playing, and games. The book contains a directory.of publishers and author anl title indexes.