Afolayan Gbenga Emmanuel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Adult Female Overweight and Obesity Prevalence in Seven

Preprints (www.preprints.org) | NOT PEER-REVIEWED | Posted: 5 October 2020 doi:10.20944/preprints202010.0067.v1 Adult Female Overweight and Obesity Prevalence in Seven Sub-Saharan African Countries: A Baseline Sub-National Assessment of Indicator 14 Of the Global NCD Monitoring Framework Ifeoma D. Ozodiegwu, DrPH1, Laina D. Mercer, PhD2, Megan Quinn, DrPH3, Henry V. Doctor, PhD4, Hadii M. Mamudu, PhD5 1Institute for Global Health, Feinberg School of Medicine, University, Chicago, IL, United States of America 2Institute for Disease Modeling, Bellevue, Washington, United States of America (Current address: PATH, Seattle, Washington, United States of America) 3Department of Biostatistics and Epidemiology, East Tennessee State University, Johnson City, Tennessee, United States of America 4Department of Science, Information, and Dissemination, World Health Organization, Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean, Cairo, Egypt 5Department of Health Services Management and Policy, East Tennessee State University Johnson City, Tennessee, United States of America Corresponding author: Ifeoma D. Ozodiegwu Mailing address: Abbott Hall, 710 N. Lake Shore Drive, Suite 800 Email: [email protected] Phone: 4237731809 Keywords: Overweight, obesity, prevalence, women, Africa South of the Sahara Abstract Introduction Decreasing overweight and obesity prevalence requires precise data at sub-national levels to monitor progress and initiate interventions. This study aimed to estimate baseline age- standardized overweight prevalence at the lowest administrative units among women, 18 years and older, in seven African countries. The study aims are synonymous with indicator 14 of the global non-communicable disease monitoring framework. Methods We used the most recent Demographic and Health Survey and administrative boundaries data from the GADM. Three Bayesian hierarchical models were fitted and model selection tests implemented. -

The Election Management System (Ems) Project Report

THE ELECTION MANAGEMENT SYSTEM (EMS) PROJECT REPORT Independent National Electoral Commission, Abuja ©2015 Table of Contents Table of Contents .................................................................................................................................... 2 Abbreviations .......................................................................................................................................... 3 Foreword ................................................................................................................................................. 4 Acknowledgments ................................................................................................................................... 5 List of Figures and Tables ........................................................................................................................ 6 Executive Summary ................................................................................................................................. 8 1.0 Background to the EMS Project ................................................................................................ 11 1.1 Establishment of the EMS Project Committee ......................................................................... 15 1.2 Membership .............................................................................................................................. 16 1.3 Terms of Reference .................................................................................................................. -

Poverty, Vulnerability and Livelihoods in Small Scale Fishing Communities in Nigeria

Poverty, Vulnerability and Livelihoods in Small Scale Fishing Communities in Nigeria Von der Wirtschaftswissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz Universität Hannover zur Erlangung des Grades einer Doktor der Wirtschaftswissenschaften – Doktor rerum politicarum – genehmigte Dissertation von MA (Economics) Levison S. Chiwaula geboren am 31.12.1976, in Blantyre (Malawi) 2009 Referent: Prof. Dr. Hermann Waibel Institut für Entwicklungs- und Agrarökonomik Wirtschaftswissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz Universität Hannover Korreferentin: Prof. Dr. Ulrike Grote Institut für Umweltökonomik und Welthandel Wirtschaftswissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz Universität Hannover Tag der Promotion: Mittwoch, 16 Dezember 2009 ii To Maggie and Caleb with love iii iv Acknowledgements I am indebted to numerous individuals and institutions that supported me throughout the writing of this dissertation. To begin with, I express my heartfelt gratitude to my first supervisor Prof. Dr. Hermann Waibel first and foremost for giving me the opportunity to conduct this PhD research under his supervision. In the course of the programme, his critical comments, guidance, support, and advice has been fatherly. Special thanks also to my second supervisor Prof. Dr. Ulrike Grote for her useful comments and advice. I am also thankful to the Germany Federal Ministry of Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ) and the World Fish Centre for the financial support through the project on “Food security and poverty alleviation through improved valuation and governance of river fisheries in Africa”. Without their funding, this dissertation was a non-starter. I also thank the World Fish Centre and Dr Christophe Béné, the coordinator of the project for continuous support and interest in my work. -

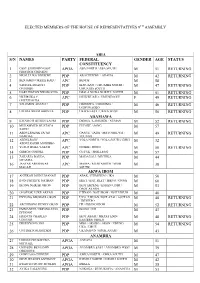

List of the Elected House of Representatives Members for the 9Th Assembly

ELECTED MEMBERS OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES 9TH ASSEMBLY ABIA S/N NAMES PARTY FEDERAL GENDER AGE STATUS CONSTITUENCY 1 OSSY EHIRIODO OSSY APGA ABA NORTH / ABA SOUTH M 51 RETURNING PRESTIGE CHINEDU 2 NKOLE UKO NDUKWE PDP AROCHUKWU / OHAFIA M 42 RETURNING 3 BENJAMIN OKEZIE KALU APC BENDE M 58 4 SAMUEL IFEANYI PDP IKWUANO / UMUAHIA NORTH / M 47 RETURNING ONUIGBO UMUAHIA SOUTH 5 DARLINGTON NWOKOCHA PDP ISIALA NGWA NORTH / SOUTH M 51 RETURNING 6 NKEIRUKA C. APC ISUIKWUATO / UMUNEOCHI F 49 RETURNING ONYEJEOCHA 7 SOLOMON ADAELU PDP OBINGWA / OSISIOMA / M 46 RETURNING UGWUNAGBO 8 UZOMA NKEM ABONTA PDP UKWA EAST / UKWA WEST M 56 RETURNING ADAMAWA 9 KWAMOTI BITRUS LAORI PDP DEMSA / LAMURDE / NUMAN M 52 RETURNING 10 MUHAMMED MUSTAFA PDP FUFORE / SONG M 57 SAIDU 11 ABDULRAZAK SA’AD APC GANYE / JADA / MAYO BELWA / M 49 RETURNING NAMDAS TOUNGO 12 ABDULRAUF APC YOLA NORTH / YOLA SOUTH/ GIREI M 32 ABDULKADIR MODIBBO 13 YUSUF BUBA YAKUB APC GOMBI / HONG M 50 RETURNING 14 GIBEON GOROKI PDP GUYUK / SHELLENG M 57 15 ZAKARIA DAUDA PDP MADAGALI / MICHIKA M 44 NYAMPA 16 JAAFAR ABUBAKAR APC MAIHA / MUBI NORTH / MUBI M 38 MAGAJI SOUTH AKWA IBOM 17 ANIEKAN JOHN UMANAH PDP ABAK / ETIM EKPO / IKA M 50 18 IFON PATRICK NATHAN PDP EKET / ESIT EKET / IBENO / ONNA M 60 19 IKONG NSIKAK OKON PDP IKOT EKPENE / ESSIEN UDIM / M 53 OBOT AKARA 20 ONOFIOK LUKE AKPAN PDP ETINAN / NSIT IBOM / NSIT UBIUM M 40 21 ENYONG MICHAEL OKON PDP UYO / URUAN /NSIT ATAI / ASUTAN M 48 RETURNING / IBESIKPO 22 ARCHIBONG HENRY OKON PDP ITU /IBIONO IBOM M 52 RETURNING 23 EMMANUEL UKPONG-UDO -

Nigeria Child Development Grant Programme Evaluation

Nigeria Child Development Grant Programme Evaluation Quantitative Midline Report Volume I: Midline findings Pedro Carneiro, Giacomo Mason, Lucie Moore and Imran Rasul November 2017 e-Pact is a consortium led by Oxford Policy Management and co-managed with Itad In association with: CDGP: Quantitative Midline Report, Volume I Preface This report presents the findings from the midline survey of the quantitative impact evaluation of the Child Development Grant Programme (CDGP) in northern Nigeria. The household survey data collection was conducted from October to December 2016 and a final round of data collection is scheduled for 2018. This report was produced by Pedro Carneiro, Giacomo Mason and Imran Rasul from Institute of Fiscal Studies (IFS) and Lucie Moore and Molly Scott from Oxford Policy Management (OPM). Disclaimer This report has been prepared by the e-Pact consortium for the named client, for services specified in the Terms of Reference and contract of engagement. The information contained in this report shall not be disclosed to any other party, or used or disclosed in whole or in part without agreement from the e-Pact consortium. For reports that are formally put into the public domain, any use of the information in this report should include a citation that acknowledges the e-Pact consortium as the author of the report. This confidentiality clause applies to all pages and information included in this report. This material has been funded by UK aid from the UK government; however, the views expressed do not necessarily reflect the UK government’s official policies. This assessment is being carried out by e-Pact. -

Nigeria Security Situation

Nigeria Security situation Country of Origin Information Report June 2021 More information on the European Union is available on the Internet (http://europa.eu) PDF ISBN978-92-9465-082-5 doi: 10.2847/433197 BZ-08-21-089-EN-N © European Asylum Support Office, 2021 Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged. For any use or reproduction of photos or other material that is not under the EASO copyright, permission must be sought directly from the copyright holders. Cover photo@ EU Civil Protection and Humanitarian Aid - Left with nothing: Boko Haram's displaced @ EU/ECHO/Isabel Coello (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0), 16 June 2015 ‘Families staying in the back of this church in Yola are from Michika, Madagali and Gwosa, some of the areas worst hit by Boko Haram attacks in Adamawa and Borno states. Living conditions for them are extremely harsh. They have received the most basic emergency assistance, provided by our partner International Rescue Committee (IRC) with EU funds. “We got mattresses, blankets, kitchen pots, tarpaulins…” they said.’ Country of origin information report | Nigeria: Security situation Acknowledgements EASO would like to acknowledge Stephanie Huber, Founder and Director of the Asylum Research Centre (ARC) as the co-drafter of this report. The following departments and organisations have reviewed the report together with EASO: The Netherlands, Ministry of Justice and Security, Office for Country Information and Language Analysis Austria, Federal Office for Immigration and Asylum, Country of Origin Information Department (B/III), Africa Desk Austrian Centre for Country of Origin and Asylum Research and Documentation (ACCORD) It must be noted that the drafting and review carried out by the mentioned departments, experts or organisations contributes to the overall quality of the report, but does not necessarily imply their formal endorsement of the final report, which is the full responsibility of EASO. -

North-West Zone

North-West Zone List of SIM Registration Centres Sokoto State Contact Number/Enquires ‐ 07030321767 S/N L.G.A City / Town Street Address 1 KWARE KWARE NAGASARI, OPPOSITE STATE SCHOOL OF NURSING 2 SOKOTO NORTH SOKOTO KARA MARKET, WESTERN BY PASS ROAD, SOKOTO NORTH 3 SOKOTO NORTH SOKOTO SOKOTO CENTRAL MOTOR PARK, CLOSE TO CENTRAL MARKET 4 SOKOTO NORTH SOKOTO UNIVERSITY QUARTERS, RUGI SAMBO 5 SOKOTO SOUTH SARKIN ZAMFARA HAJI VIDEO, OFFA ROAD OLD AIRPORT 6 SOKOTO SOUTH SARKIN ZAMFARA IN FRONT OF FREEDOM PHARMACY (DIPLOMAT AREA,CLOSE TO CITY CAMPUS) 7 SOKOTO SOUTH SARKIN ZAMFARA SANGONGORO ‐ OLD MARKET AT MARAFA DAN BABA AREA 8 SOKOTO SOUTH SARKIN ZAMFARA MARBERA, CLOSE TO AIR PORT 9 WAMAKO WAMAKO YAHAYA‐GUSAU PRIMARY SCHOOL, OFFA ROAD, AIRPORT 10 WAMAKO WAMAKO GOVERNMENT DAY SECONDARY SCHOOL WAMAKO 11 WAMAKO WAMAKO GAWON‐NAMA AREA 12 GWADABAWA GWADABAWA INFRONT OF GWADABAWA 2 HOSPITAL , KANWURI‐SARKI AREA, GWADABAWA 13 DANGE‐SHUNI DANGE INFRONT OF ARMY BARRACK, BARRACK AREA, DANGE‐SHUNI 14 GWADABAWA GWADABAWA INFRONT OF GWADABAWA MOTOR PARK, GWADABAWA 15 ILLELA ILLELA INFRONT OF ILLELA MARKET, ILLELA 16 TAMBUWAL TAMBUWAL TAMBUWAL MOTOR PARK, TAMBUWAL 17 DANGE‐SHUNI DANGE INSIDE DANGE‐SHUNI CENTRAL MARKET, DANGE‐SHUNI 18 BODINGA BODINGA INFRONT OF BODINGA MARKET, BODINGA 19 YABO YABO INFRONT OF YABO LOCAL GOVT SECRETARIAT, YABO 20 TANGAZA GIDAN MADI ALHAJI HUSSEIN PHARMACY, GARKA MALLAM SABO AREA 21 BODINGA BODINGA INSIDE BODINGA LOCAL GOVT SECRETARIAT, BODINGA 22 ISA ISA TURETA ROAD, ISA TOWN. 23 BINJI BINJI TUDUN KOSE, GIDAN MAIDEBE BINJI 24 SILAME SILAME BESIDE SANJU SUNNY NIG LTD 25 SOKOTO NORTH SOKOTO SOKOTO CINEMA, CLOSE TO EO'S RESIDENT/ ILLELE GARAGE WATER BORD SOKOTO 26 SOKOTO NORTH SOKOTO OPPOSITE ISA MAI KWARE MOSQUE 27 SOKOTO SOUTH SARKIN ZAMFARA NEAR SULTAN ATIKU SECONDARY SCHOOL 28 TURETA TURETA TURETA MARKET 29 SOKOTO NORTH SOKOTO MORE BYEPASS ROAD 30 SHAGARI SHAGARI SHAGARI MARKET 31 SOKOTO SOUTH SARKIN ZAMFARA NUMBER 16, SULTAN IBRAHIM, DANSUKI ROAD. -

GREEN CHAMBER: 9TH HOUSE of REPRESENTATIVES. There Are

GREEN CHAMBER: 9TH HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES. There are expectations for the 9th session of the lower house of the National Assembly called the Green Chamber or THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES. They are elected to represent their people in a determined number of people per population. According to the website of the House of Representatives, 360 people are expected to be elected at the 2019 General Election. South East South South South West State Seat State Seat State Seat Anambra 11 Rivers 13 Lagos 24 Imo 10 Akwa Ibom 10 Oyo 14 Abia 8 Delta 10 Ogun 9 Enugu 8 Edo 9 Ondo 9 Ebonyi 6 Cross River 8 Osun 9 Total 43 Balyesa 5 Ekiti 6 Total 55 Total 71 North East North Central North West FCT State Seat State Seat State Seat FCT Seat Bauchi 12 Benue 11 Kano 24 FCT 2 Borno 10 Niger 10 Kaduna 16 Total 2 Adamawa 8 Kogi 9 Katsina 15 Gombe 6 Plateau 8 Jigawa 11 Taraba 6 Kwara 6 Sokoto 11 Yobe 6 Nasarawa 5 Kebbi 8 Total 48 Total 49 Zamfara 7 Total 92 Source: INEC. The election into this house was held on 23rd February along with the Presidential and Senate elections. 1 The Cable posted the summary of the results as above. It shows that The All Peoples Congress already have the majority in the House. INEC posted the list of those victorious in the election. INDEPENDENT NATIONAL ELECTORAL COMMISSION 2019 HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ELECTION 23RD FEBRUARY 2019 LIST OF ELECTED CANDIDATES STATE SN CONSTITUENCY CANDIDATE GENDE R PARTY REMARKS ABIA 8 Seats 1 ABA NORTH / ABA SOUTH - SUPPLEMENTARY 2 AROCHUKWU / OHAFIA - NKOLE UKO NDUKWE M PDP 3 BENDE - BENJAMIN OKEZIE KALU M APC 4 IKWUANO / UMUAHIA NORTH / UMUAHIA SOUTH - SAMUEL IFEANYI ONUIGBO M PDP 5 ISIALA NGWA NORTH / SOUTH - DARLINGTON NWOKOCHA M PDP 6 ISUIKWUATO / UMUNEOCHI - NKEIRUKA C. -

Final Report

Guri, Birnin Kudu & Gwiwa LGAs, Jigawa State, Nigeria 21st Nov – 20th Dec 2013 Joseph Njau, Ifeanyi Maduanusi & Emmanuel Bimba Funded by .I. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The SQUEAC survey in Jigawa state has been completed with funding by UK Government through Department for International Development (DFID) that is funding the project ‘Working to Improve Nutrition in Northern Nigeria ‘(WINNN) under which SQUEAC is a deliverable. Valuable guidance and support was extended by the HQ technical team comprising Oscar Serrano (Health & Nutrition Advisor), Saul Guerrero (Head of Technical Development-ACF-UK) and Jose Luis Alvarez (Coverage Monitoring Network- CMN Project Coordinator). Tamanna Ferdous (Nutrition coordinator-ACF Nigeria) was instrumental in setting the pace for the SQUEAC implementation process in Jigawa. Joseph Njau (CMAM Program Coverage Manager) trained the coverage teams and supervised the implementation process remotely. Ifeanyi Maduanusi (CMAM Program Coverage Officer) and Emmanuel Bimba (M&E Technical Advisor-Jigawa) cascaded the knowledge and supervision of the SQUEAC survey to the nutrition focal persons (NFPs) and survey enumerators at the local government areas (LGAs) of Guri, Birnin Kudu and Gwiwa. Abdulahi Magama (State Technical Advisor-Jigawa) offered valuable support in communication to the State and LGA authorities, recruitment and organization of the program staff and survey teams for successful completion of the SQUEAC survey. The program staff in individual LGAs are appreciated in a special way for availing themselves and the needed information. The State Ministry of Health (SMoH) and Gunduma Health System Board (GHSB) were key in granting permission for the SQUEAC team to gain access to the LGA and implement the SQUEAC survey. -

Nigeria Niger

Cholera - Nigeria hotspots location by state Platform Cholera Jigawa State West and Central Africa Niger Maigatari Biriniwa Birinawa Gwiwa Babura Yankwashi Gwiwa Yankwashi Guri Kiri Kasamma Sule Tankarka Maigatari Roni Kazaure Sule Tankakar Gumel Guri Kazaure Babura Gumel Roni Malam-Maduri Katsina Malam Maduri Kiri Kasama Gagarawa Kuagama Hotspots typology in the State Garki Hadejia Hadejia Garki Gagarawa YobeHotspot type T.1: Kaugama Auyo Auyo High priority area with a high frequency and a long duration. Taura Taura Miga Kaffin-Hausa Miga Ringim Ringim Hotspot type T.2: Kafin Hausa Medium priority area with a moderate frequency Jahun Jahun and a long duration Hotspots distribution in the State Nigeria kiyawa Dutse Kiyawa Dutse 2 1 Hotspots Type 1 Hotspot Type 2 Kano Buji Buji Bimin Kudu Taura Birnin Kudu Birnin Kudu Bauchi Ringim Gwaram Gwaram Legend Kaduna Countries State Main roads Gombe 0 70 140 280 420 560 XXX LGA (Local Governmental Area) Hydrography Kilometers XXX Cities (State capital, LGA capital, and other towns) Date of production: January 21, 2016 Source: Ministries of Health of the countries members of the Cholera platform Contact : Cholera project - UNICEF West and Central Africa Regionial Office (WCARO) Feedback : Coordination : Julie Gauthier | [email protected] Information management : Alca Kuvituanga | [email protected] : of support the With The epidemiological data is certified and shared by national authorities towards the cholera platform members. Geographical names, designations, borders presented do not imply any official recognition nor approval from none of the cholera platform members . -

(SQUEAC) Kiyawa LGA CMAM Program Jigawa State, Northern Nigeria June-July 2014

Semi-Quantitative Evaluation of Access and Coverage (SQUEAC) Kiyawa LGA CMAM Program Jigawa State, Northern Nigeria June-July 2014 Joseph Njau, Ifeanyi Maduanusi, Chika Obinwa, Francis Ogum, Zulai Abdulmalik, and Janet Adeoye ACF International 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Kiyawa LGA SQUEAC 1 has been implemented through generous support of the Children Investment Fund Foundation (CIFF). The ACF Nigeria Coverage Assessment Team are grateful to the following for their valuable contributions towards the successful completion of the Kiyawa Local Government Area (LGA) SQUEAC assessment. Firstly, Gunduma Health System Board (GHSB) Jigawa State authorized the implementation of the SQUEAC assessment in Kiyawa LGA. Usman Tahir (Director General GHSB), and Kabir Ibrahim (Director Primary Health Care GHSB) were very supportive throughout the exercise, acting as the link between the State and the CMAM 2 Coverage assessment team. Aisha Aminu Zango, the State Nutrition Officer (SNO), Husaini Ado of National Population Commission (NPopC), Ibrahim Haruna Head of Department (HoD) Kiyawa LGA Water, Sanitation and Hygiene (WASH) Program and Suleiman Muhammad the Nutrition Focal Person (NFP) of Kiyawa LGA are acknowledged for providing the coverage assessment team with client/beneficiary records, anecdotal program information and the LGA maps. Gloria Njoku, the ACF’s Head of Base, at Dutse office is appreciated for introducing the team to the various stakeholders and giving logisitical support to the SQUEAC investigation team. Peter Magoh the ACF security manager, and Abubakar Kawu (program support officer) conducted a very helpful security and logistics assessment prior to the implementation of the SQUEAC assessment. Abubakar played a key role in logistics and administrative support during the SQUEAC implementation period. -

PROJECT REPORT Author

Technical Support on the Elaboration of the Rural Electrification Master Plan of Jigawa State (Northern Nigeria) PROJECT REPORT Author: Manuel Villavicencio Director: Dr. Enrique Velo García Session: June 2012 Màster Interuniversitari UB-UPC d’Enginyeria en Energia Màster Interuniversitari UB-UPC d’Enginyeria en Energia Sol·licitud d’acceptació de presentació del Projecte Final de Màster i sol·licitud de defensa pública. Alumne: Manuel Villavicencio DNI: Y-0717761-Z Títol: Director: Prof. Enric Velo Acceptació de la presentació del projecte: Confirmo l’acceptació de la presentació del Projecte Final de Màster. Per a que consti, Cognoms, nom (director del Projecte) Sol·licito: La defensa pública del meu Projecte Final de Màster. Per a que consti, Manuel Daniel Villavicencio Rojas Barcelona, ........ de .............. de ....... Màster Interuniversitari UB-UPC d’Enginyeria en Energia Acta d’Avaluació de Projecte Curs: Codi UPC: 33563 Data defensa: Qualificació: Alumne: Manuel Villavicencio DNI: Y-0717761-Z Títol: Technical support for the elaboration of the Jigawa State`s electrification master plan Director: Prof. Enric Velo Director: Ponent: Tribunal President: Vocals: Suplents: Observacions Signatura Convocatòria Ordinària, Convocatòria Extraordinària, Cognoms, nom (President) Cognoms, nom (President) Cognoms, nom (Vocal) Cognoms, nom (Vocal) Cognoms, nom (Vocal) Cognoms, nom (Vocal) SUPPORT FOR THE ELABORATION OF THE MASTER PLAN FOR THE JIGAWA STATE ELECTRIFICATION ENGR. MANUEL VILLAVICENCIO ABSTRACT Jigawa State, with a rural population of 85% and 20% of electricity access among other basic services deficiencies, is one of the poorest states of Nigeria The electrification targets of the state were assessed from a decentralized approach. Solar potential, biomass residues and Jatropha Curcas harvest are the main local resources to be considered for power generation.