Issuespaper the Impact of Selective Food and Non-Alcoholic Beverage Taxes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Proposal for a Simple Average-Based Progressive Taxation System

A proposal for a simple average-based progressive taxation system DIRK-HINNERK FISCHER, Ph.D.* SIMONA FERRARO, Ph.D.* Preliminary communication** JEL: H21, H24 https://doi.org/10.3326/pse.43.2.2 * We would like to thank the participants of the FairTax special session of the conference “Enterprise and Competitive Environment 2017” for their comments on a draft of this paper. We would also like to thank Ton Notermans of Tallinn University of Technology for his advice on the paper as well as the two anonymous referees. ** Received: January 9, 2019 Accepted: April 1, 2019 Dirk-Hinnerk FISCHER Tallinn University of Technology, Akadeemia tee 3, 12611 Tallinn, Estonia e-mail: [email protected] ORCiD: 0000-0002-1040-8347 Simona FERRARO Tallinn University of Technology, Akadeemia tee 3, 12611 Tallinn, Estonia e-mail: [email protected] ORCiD: 0000-0001-5175-5348 Abstract 142 This paper is a first theoretical presentation of a simple progressive taxation sys- tem. The system is based on two adaptations of one easily calculable formula that is based on the societal average income of the previous year. The system contrib- utes to academic discussions as it is a novel approach. It is a progressive tax that 43 (2) 141-165 (2019) ECONOMICS PUBLIC does not discriminate against anyone as the progression increases continuously SECTOR and the increase in tax payment does not go beyond the additional income. The analysis in the paper shows that the core advantage of the system is its simple, transparent and adaptable mechanism. Keywords: taxation, flat tax, progressive tax, taxation efficiency 1 INTRODUCTION A DIRK PROPOSAL Complicated taxation systems do not only lead to a significant increase in admin- - HINNERK istrative costs for all parties involved, but they can also lead to unjustified tax FOR exemptions and loopholes. -

Regressive Sin Taxes

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES REGRESSIVE SIN TAXES Benjamin B. Lockwood Dmitry Taubinsky Working Paper 23085 http://www.nber.org/papers/w23085 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 January 2017 We thank Hunt Allcott, Alan Auerbach, Raj Chetty, Stefano DellaVigna, Emmanuel Farhi, Xavier Gabaix, Nathaniel Hendren, Louis Kaplow, David Laibson, Erzo F.P. Luttmer, Matthew Rabin, Alex Rees-Jones, Emmanuel Saez, Jim Sallee, Florian Scheuer, Stefanie Stantcheva, Matthew Weinzierl, and participants at seminars and conferences for helpful comments and discussions. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research. NBER working papers are circulated for discussion and comment purposes. They have not been peer- reviewed or been subject to the review by the NBER Board of Directors that accompanies official NBER publications. © 2017 by Benjamin B. Lockwood and Dmitry Taubinsky. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the source. Regressive Sin Taxes Benjamin B. Lockwood and Dmitry Taubinsky NBER Working Paper No. 23085 January 2017 JEL No. H0,I18,I3,K32,K34 ABSTRACT A common objection to “sin taxes”—corrective taxes on goods like cigarettes, alcohol, and sugary drinks, which are believed to be over-consumed—is that they fall disproportionately on low-income consumers. This paper studies the interaction between corrective and redistributive motives in a general optimal taxation framework. On the one hand, redistributive concerns amplify the corrective benefits of a sin tax when sin good consumption is concentrated on the poor, even when bias and demand elasticities are constant across incomes. -

Taxation of Land and Economic Growth

economies Article Taxation of Land and Economic Growth Shulu Che 1, Ronald Ravinesh Kumar 2 and Peter J. Stauvermann 1,* 1 Department of Global Business and Economics, Changwon National University, Changwon 51140, Korea; [email protected] 2 School of Accounting, Finance and Economics, Laucala Campus, The University of the South Pacific, Suva 40302, Fiji; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +82-55-213-3309 Abstract: In this paper, we theoretically analyze the effects of three types of land taxes on economic growth using an overlapping generation model in which land can be used for production or con- sumption (housing) purposes. Based on the analyses in which land is used as a factor of production, we can confirm that the taxation of land will lead to an increase in the growth rate of the economy. Particularly, we show that the introduction of a tax on land rents, a tax on the value of land or a stamp duty will cause the net price of land to decline. Further, we show that the nationalization of land and the redistribution of the land rents to the young generation will maximize the growth rate of the economy. Keywords: taxation of land; land rents; overlapping generation model; land property; endoge- nous growth Citation: Che, Shulu, Ronald 1. Introduction Ravinesh Kumar, and Peter J. In this paper, we use a growth model to theoretically investigate the influence of Stauvermann. 2021. Taxation of Land different types of land tax on economic growth. Further, we investigate how the allocation and Economic Growth. Economies 9: of the tax revenue influences the growth of the economy. -

Ecotaxes: a Comparative Study of India and China

Ecotaxes: A Comparative Study of India and China Rajat Verma ISBN 978-81-7791-209-8 © 2016, Copyright Reserved The Institute for Social and Economic Change, Bangalore Institute for Social and Economic Change (ISEC) is engaged in interdisciplinary research in analytical and applied areas of the social sciences, encompassing diverse aspects of development. ISEC works with central, state and local governments as well as international agencies by undertaking systematic studies of resource potential, identifying factors influencing growth and examining measures for reducing poverty. The thrust areas of research include state and local economic policies, issues relating to sociological and demographic transition, environmental issues and fiscal, administrative and political decentralization and governance. It pursues fruitful contacts with other institutions and scholars devoted to social science research through collaborative research programmes, seminars, etc. The Working Paper Series provides an opportunity for ISEC faculty, visiting fellows and PhD scholars to discuss their ideas and research work before publication and to get feedback from their peer group. Papers selected for publication in the series present empirical analyses and generally deal with wider issues of public policy at a sectoral, regional or national level. These working papers undergo review but typically do not present final research results, and constitute works in progress. ECOTAXES: A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF INDIA AND CHINA1 Rajat Verma2 Abstract This paper attempts to compare various forms of ecotaxes adopted by India and China in order to reduce their carbon emissions by 2020 and to address other environmental issues. The study contributes to the literature by giving a comprehensive definition of ecotaxes and using it to analyse the status of these taxes in India and China. -

PROGRESSIVE TAX REVENUE RAISERS HI TAX FAIRNESS January 2021

YES PROGRESSIVE TAX REVENUE RAISERS HI TAX FAIRNESS January 2021 www.hitaxfairness.org HAWAI‘I CAN PULL ITS ECONOMY OUT OF RECESSION BY USING TAX FAIRNESS MEASURES TO RAISE REVENUE & AVOID CUTS As Hawai‘i’s leaders head into 2021 Revenue Proposal Revenue Estimate while facing high unemployment (Millions) rates, an economic recession, and state budget shortfalls, it’s important Low High to keep in mind that deep government Raise income taxes on the richest 2% $12.6 $100.2 spending cuts would have a devastating effect on our already Phase out low tax rates $18.5 $153.9 injured economy, as well as hobble for those at the top social services that have become more and more essential during the Tax investments the same way $80.2 $80.2 pandemic crisis. regular income is taxed That’s because spending is the fuel Increase taxes on wealthy inheritances $6.6 $18.3 that keeps our economic engines running. As the private sector Raise corporate taxes $2.9 $103.0 engine of our economy sputters, the government needs to throttle Make global corporations pay taxes $38.0 $38.0 up its spending in order to keep the in Hawai‘i economy going. Past recessions have Make REITs pay their fair share of taxes $30.0 $60.0 shown us that state spending cuts just exacerbate the economic damage. Increase taxes on the sales of mansions $17.0 $71.5 At this crucial time, cutting government spending would be akin Tax vaping and increase $21.1 $24.1 to taking our foot off the pedal and other tobacco taxes letting the second engine of the Place a fee on sugary drinks $65.8 $65.8 economy sputter as well. -

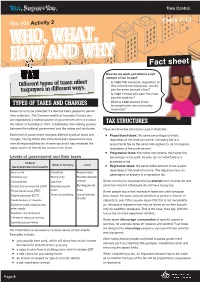

WHO, WHAT, HOW and WHY Fact Sheet

Ta x , Super+You. Take Control. Years 7-12 Tax 101 Activity 2 WHO, WHAT, HOW AND WHY Fact sheet How do we work out what is a fair amount of tax to pay? • Is it fair that everyone, regardless of Different types of taxes affect their income and expenses, should taxpayers in different ways. pay the same amount of tax? • Is it fair if those who earn the most pay the most tax? • What is a fair amount of tax TYPES OF TAXES AND CHARGES for people who use community resources? Taxes can only be collected if a law has been passed to permit their collection. The Commonwealth of Australia Constitution Act established a federal system of government when it created TAX STRUCTURES the nation of Australia in 1901. It distributes law-making powers between the national government and the states and territories. There are three tax structures used in Australia: Each level of government imposes different types of taxes and Proportional taxes: the same percentage is levied, charges. During World War II the Australian Government took regardless of the level of income. Company tax is a over all responsibilities for income tax and it has remained the proportional tax as the same rate applies for all companies, major source of federal tax revenue ever since. regardless of the profit earned. Progressive taxes: the higher the income, the higher the Levels of government and their taxes percentage of tax paid. Income tax for individuals is a Federal progressive tax. State or territory Local (Australian/Commonwealth) Regressive taxes: the same dollar amount of tax is paid, regardless of the level of income. -

SUGARY DRINK TAXES: How a Sugary Drink Tax Can Benefit Rhode Island

SUGARY DRINK TAXES: how a sugary drink tax can benefit Rhode Island As of now, seven cities across the nation have successfully implemented sugar-sweetened beverage (SSB) taxes, also known as sugary drink taxes. Evaluations of these taxes not only show the important health benefits of adopting this tax but shed light on the best strategies for implementation of this policy. Below are some valuable findings from the cities that have implemented SSB taxes and how this data can be used to implement the tax in Rhode Island. How do SSB taxes impact health? Currently, SSBs are the leading source of added sugar in the American diet and there is extensive evidence showing an association between these beverages and an increased risk of type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, dental caries, osteoporosis, and obesity.1 Yet, multiple cities that have implemented the SSB tax have seen downward trends in the consumption of SSBs that could lead to improved health outcomes and greater healthcare savings.1 Three years after implementing the tax, Berkeley saw a 50% average decline in SSB consumption with an increase in water consumption. Similarly, in Philadelphia, the probability of consuming regular soda fell by 25% and the intake of water rose by 44% only six months after the tax was effective.2 Philadelphia adults who typically consumed one regular soda per day before the tax transitioned to drinking soda every three days after the tax.2 This shift in behavior has very important health implications; SSB taxes are linked with a significant reduction in the incidence of cardiovascular diseases and with a decrease in BMI and body weight. -

Corporate Tax Reform: Issues for Congress

Corporate Tax Reform: Issues for Congress Updated June 11, 2021 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov RL34229 SUMMARY RL34229 Corporate Tax Reform: Issues for Congress June 11, 2021 In 2017, the corporate tax rate was cut from 35% to 21%, major changes were made in the international tax system, and changes were made in other corporate provisions, including Jane G. Gravelle allowing expensing (an immediate deduction) for equipment investment. Recently, proposals Senior Specialist in have been made to increase revenue from corporate taxes, including an increased tax rate, and Economic Policy revise the international tax provisions to raise revenue. These revenues may be needed to fund additional spending or reduce the deficit. Some level of corporate tax is needed to prevent corporations from becoming a tax shelter for high-income taxpayers. The lower corporate taxes adopted in 2017 made the corporate form of organization more attractive to individuals. At the same time, higher corporate taxes have traditionally led to concerns about economic distortions arising from the corporate tax and newer concerns arising from the increasingly global nature of the economy. In addition, leading up to the 2017 tax cut, some claimed that lowering the corporate tax rate would raise revenue because of the behavioral responses, an effect that is linked to an open economy. Although the corporate tax has generally been viewed as contributing to a more progressive tax system because the burden falls on capital income and thus on higher-income individuals, claims were also made that the burden falls not on owners of capital, but on labor income—an effect also linked to an open economy. -

Taxing Inheritances, Taxing Estates James R

University of Michigan Law School University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository Articles Faculty Scholarship 2010 Taxing Inheritances, Taxing Estates James R. Hines Jr. University of Michigan Law School, [email protected] Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/articles/198 Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/articles Part of the Taxation-Federal Estate and Gift ommonC s, and the Tax Law Commons Recommended Citation Hines, James R., Jr. "Taxing Inheritances, Taxing Estates." Tax L. Rev. 63, no. 1 (2010): 189-207. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles by an authorized administrator of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Taxing Inheritances, Taxing Estates JAMES R. HINES, JR.* I. INTRODUCTION Just about every living American knows that there is heated politi- cal controversy over the taxation of estates and inheritances. The con- troversy has several sources, prominently including both the absence of a shared concept of tax fairness and a tension between the universal dislike of being taxed and the government's desperate need for reve- nue. Popular rallying cries and the tax reduction experiments con- ducted by the U.S. Congress and the Bush Administration since 2001 have kept the estate tax on the political front burner,' where it may remain for years to come. How should those who are coolly detached from Washington polit- ics think about the taxation of wealth transfers at death? The recent intriguing proposal by Lily Batchelder 2 to replace the U.S. -

Progressive Tax Reform and Equality in Latin America

PROGRESSIVE TAX REFORM AND EQUALITY IN LATIN AMERICA EDITED BY James E. Mahon Jr. Marcelo Bergman Cynthia Arnson WWW.WILSONCENTER.ORG/LAP THE WILSON CENTER, chartered by Congress as the official memorial to President Woodrow Wilson, is the nation’s key nonpartisan policy forum for tackling global issues through independent research and open dialogue to inform actionable ideas for Congress, the Administration, and the broad- er policy community. Conclusions or opinions expressed in Center publications and programs are those of the authors and speakers and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Center staff, fellows, trustees, advisory groups, or any individu- als or organizations that provide financial support to the Center. Please visit us online at www.wilsoncenter.org. Jane Harman, Director, President and CEO BOARD OF TRUSTEES Thomas R. Nides, Chair Sander R. Gerber, Vice Chair Public members: William Adams, Acting Chairman of the National Endowment for the Humanities; James H. Billington, Librarian of Congress; Sylvia Mathews Burwell, Secretary of Health and Human Services; G. Wayne Clough, Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution; Arne Duncan, Secretary of Education; David Ferriero, Archivist of the United States; John F. Kerry. Designated appointee of the president from within the federal government: Fred P. Hochberg, Chairman and President, Available from: Export-Import Bank of the United States Latin American Program Private Citizen Members: John T. Casteen III, Charles E. Cobb Jr., Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars Thelma Duggin, Lt. Gen Susan Helms, USAF (Ret.), Barry S. Jackson, One Woodrow Wilson Plaza Nathalie Rayes, Jane Watson Stetson 1300 Pennsylvania Avenue NW Washington, DC 20004-3027 WILSON NATIONAL CABINET: Ambassador Joseph B. -

Land Value Is a Progressive and Efficient Property Tax Base: Evidence from Victoria

Land value is a progressive and efficient property tax base: Evidence from Victoria Cameron K. Murray,∗ Jesse Hermansy November 25, 2019 Abstract Property taxes are a common revenue source for city governments. There are two property tax bases available|land value (site value, SV), or total property value (capital improved value, CIV). The choice of property tax base has implications for both the distribution and efficiency of the tax. We provide new evidence in favour of SV being both the more progressive and efficient property tax base. First, we use three Victorian datasets at different levels of geographic aggregation to model the SV-CIV ratio as a function of various household income measures. At all three levels, a higher SV-CIV ratio occurs in areas with higher incomes, implying that SV is the more progressive property tax base. Our range of results suggests that a one percent increase in the income of an area is associated with a 0.10 to 0.57 percentage point increase in the SV-CIV ratio. Second, we use historical council data to conduct a difference-in-difference analysis to compare the effect of switching from a CIV to SV tax base on the number of building approvals and value of construction investment. We find that switching from CIV to SV as a property tax base is associated with a 20% increase in the value of new residential construction. This is consistent with the view that changes to land value tax rates are non-neutral with respect to the timing of capital investment on vacant and under-utilised land, which we also demonstrate theoretically. -

Progressive Wealth Taxation

BPEA Conference Drafts, September 5–6, 2019 Progressive Wealth Taxation Emmanuel Saez, University of California, Berkeley Gabriel Zucman, University of California, Berkeley Conflict of Interest Disclosure: Emmanuel Saez holds the Chancellor’s Professorship of Tax Policy and Public Finance and directs the Center for Equitable Growth at the University of California, Berkeley; Gabriel Zucman is an assistant professor of economics at the University of California, Berkeley. Beyond these affiliations, the authors did not receive financial support from any firm or person for this paper or from any firm or person with a financial or political interest in this paper. They are currently not officers, directors, or board members of any organization with an interest in this paper. No outside party had the right to review this paper before circulation. The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors, and do not necessarily reflect those of the University of California, Berkeley. The authors have advised several presidential campaigns recently on the issue of a wealth tax. Progressive Wealth Taxation∗ Emmanuel Saez Gabriel Zucman UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Conference Draft: September 4, 2019 Abstract This paper discusses the progressive taxation of household wealth. We first discuss what wealth is, how it is distributed, and how much revenue a progressive wealth tax could generate in the United States. We try to reconcile discrepancies across wealth data sources. Second, we discuss the role a wealth tax can play to increase the overall progressivity of the US tax system. Third, we discuss the empirical evidence on wealth tax avoidance and evasion as well as tax enforcement policies.