David Darchiashvili GEORGIAN SECURITY SECTOR

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

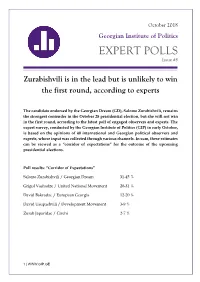

EXPERT POLLS Issue #8

October 2018 Georgian Institute of Politics EXPERT POLLS Issue #8 Zurabishvili is in the lead but is unlikely to win the first round, according to experts The candidate endorsed by the Georgian Dream (GD), Salome Zurabishvili, remains the strongest contender in the October 28 presidential election, but she will not win in the first round, according to the latest poll of engaged observers and experts. The expert survey, conducted by the Georgian Institute of Politics (GIP) in early October, is based on the opinions of 40 international and Georgian political observers and experts, whose input was collected through various channels. In sum, these estimates can be viewed as a “corridor of expectations” for the outcome of the upcoming presidential elections. Poll results: “Corridor of Expectations” Salome Zurabishvili / Georgian Dream 31-45 % Grigol Vashadze / United National Movement 20-31 % David Bakradze / European Georgia 12-20 % David Usupashvili / Development Movement 3-9 % Zurab Japaridze / Girchi 2-7 % 1 | WWW.GIP.GE Figure 1: Corridor of expectations (in percent) Who is going to win the presidential election? According to surveyed experts (figure 1), Salome Zurabishvili, who is endorsed by the governing Georgian Dream party, is poised to receive the most votes in the upcoming presidential elections. It is likely, however, that she will not receive enough votes to win the elections in the first round. According to the survey, Zurabishvili’s vote share in the first round of the elections will be between 31-45%. She will be followed by the United National Movement (UNM) candidate, Grigol Vashadze, who is expected to receive between 20-31% of votes. -

Russian Hybrid Tactics in Georgia

Russian Hybrid Tactics in Georgia Niklas Nilsson SILK ROAD PAPER January 2018 Russian Hybrid Tactics in Georgia Niklas Nilsson © Central Asia-Caucasus Institute & Silk Road Studies Program – A Joint Transatlantic Research and Policy Center American Foreign Policy Council, 509 C St NE, Washington D.C. Institute for Security and Development Policy, V. Finnbodavägen 2, Stockholm-Nacka, Sweden www.silkroadstudies.org “Russian Hybrid Tactics in Georgia” is a Silk Road Paper published by the Central Asia- Caucasus Institute and Silk Road Studies Program, Joint Center. The Silk Road Papers Series is the Occasional Paper series of the Joint Center, and addresses topical and timely subjects. The Joint Center is a transatlantic independent and non-profit research and policy center. It has offices in Washington and Stockholm and is affiliated with the American Foreign Policy Council and the Institute for Security and Development Policy. It is the first institution of its kind in Europe and North America, and is firmly established as a leading research and policy center, serving a large and diverse community of analysts, scholars, policy-watchers, business leaders, and journalists. The Joint Center is at the forefront of research on issues of conflict, security, and development in the region. Through its applied research, publications, research cooperation, public lectures, and seminars, it functions as a focal point for academic, policy, and public discussion regarding the region. The opinions and conclusions expressed in this study are those of -

Who Owned Georgia Eng.Pdf

By Paul Rimple This book is about the businessmen and the companies who own significant shares in broadcasting, telecommunications, advertisement, oil import and distribution, pharmaceutical, privatisation and mining sectors. Furthermore, It describes the relationship and connections between the businessmen and companies with the government. Included is the information about the connections of these businessmen and companies with the government. The book encompases the time period between 2003-2012. At the time of the writing of the book significant changes have taken place with regards to property rights in Georgia. As a result of 2012 Parliamentary elections the ruling party has lost the majority resulting in significant changes in the business ownership structure in Georgia. Those changes are included in the last chapter of this book. The project has been initiated by Transparency International Georgia. The author of the book is journalist Paul Rimple. He has been assisted by analyst Giorgi Chanturia from Transparency International Georgia. Online version of this book is available on this address: http://www.transparency.ge/ Published with the financial support of Open Society Georgia Foundation The views expressed in the report to not necessarily coincide with those of the Open Society Georgia Foundation, therefore the organisation is not responsible for the report’s content. WHO OWNED GEORGIA 2003-2012 By Paul Rimple 1 Contents INTRODUCTION .........................................................................................................3 -

Letter of Concern of April 2015

7 April 2015 Mr Giorgi Margvelashvili President of Georgia Abdushelishvili st. 1, Tbilisi, Georgia1 Mr Irakli Garibashvili Prime Minister of Georgia 7 Ingorokva St, Tbilisi 0114, Georgia2 Mr David Usupashvili Chairperson of the Parliament of Georgia 26, Abashidze Street, Kutaisi, 4600 Georgia Email: [email protected] Political leaders in Georgia must stop slandering human rights NGOs Mr President, Mr Prime Minister, Mr Chairperson, We, the undersigned members and partners of the Human Rights House Network and the South Caucasus Network of Human Rights Defenders, call upon political leaders in Georgia to stop slandering non-governmental organisations with unfounded accusations and suggestions that their work would harm the country. Since October 2013, public verbal attacks against human rights organisations by leading political figures in Georgia have increased. The situation is starting to resemble to an anti-civil society campaign. In October 2013, the Vice Prime Minister and Minister for Energy Resources of Georgia, Kakhi Kaladze, criticised the non-governmental organisations, which opposed the construction of a hydroelectric power plant and used derogatory terms to express his discontent over their protest.3 In May 2014, you, Mr Prime Minister, slammed NGOs participating in the campaign about privacy rights, “This Affects You,”4 and stated that they “undermine” the functioning of the State and “damage of the international reputation of the country.”5 Such terms do not value disagreement with NGOs and their participation in public debate, but rather delegitimised their work. Further more, the Prime Minister’s statement encouraged other politicians to make critical statements about CSOs and start activities against them. -

Espionage Against Poland in the Documents and Analyses of the Polish Special Services (1944–1989) – As Illustrated by the Intelligence Activities of the USA

DOI 10.14746/ssp.2016.1.8 Remigiusz ROSICKI Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznań Espionage against Poland in the Documents and Analyses of the Polish Special Services (1944–1989) – as Illustrated by the Intelligence Activities of the USA Abstract: The text is treats of the espionage against Poland in the period 1944–1989. The above analysis has been supplemented with the quantitative data from the period 1944–1984 as regards those convicted for participating in, acting for, and passing on information to the foreign intelligence agencies. The espionage issues were presented on the example of the American intelligence activity, which was illustrated by the cases of persons who were convicted for espionage. While examining the research thesis, the author used the documents and analyses prepared by the Ministry of In- ternal Affairs, which were in its major part addressed to the Security Service and the Citizens’ Militia officers. The author made an attempt at the verification of the fol- lowing research hypotheses: (1) To what extent did the character of the socio-political system influence the number of persons convicted for espionage against Poland in the period under examination (1944–1989)?; (2) What was the level of foreign intel- ligence services’ interest in Poland before the year 1990?; (3) Is it possible to indicate the specificity of the U.S. intelligence activity against Poland? Key words: espionage, U.S. espionage, intelligence activities, counterespionage, Polish counterintelligence, special services, state security Introduction he aim of this text is to present the level of knowledge among the au- Tthorities responsible for the state security and public order about the intelligence activities conducted against Poland in the period 1944–1989. -

Transformation of the Special Services in Poland in the Context of Political Changes

Scientific Journal of the Military University of Land Forces ISSN:2544-7122(print),2545-0719(online) 2020,Volume52,Number3(197),Pages557-573 DOI:10.5604/01.3001.0014.3926 Original article Transformation of the special services in Poland in the context of political changes Marian Kopczewski1* , Zbigniew Ciekanowski2 , Anna Piotrowska3 1 FacultyofSecuritySciences, GeneralTadeuszKościuszkoMilitaryUniversityofLandForces,Wrocław,Poland, e-mail:[email protected] 2 FacultyofEconomicandTechnicalSciences, PopeJohnPaulIIStateSchoolofHigherEducationinBiałaPodlaska,Poland, e-mail:[email protected] 3 FacultyofNationalSecurity,WarStudiesUniversity,Warsaw,Poland, e-mail:[email protected] INFORMATION ABSTRACT Article history: ThearticlepresentsthetransformationofspecialservicesinPolandagainst Submited:16August2019 thebackgroundofpoliticalchanges.Itpresentstheactivitiesofsecuritybod- Accepted:19May2020 ies–civilandmilitaryintelligenceandcounterintelligenceduringthecommu- Published:15September2020 nistera.Theirtaskwastostrengthencommunistpower,eliminateopponents ofthesystem,strengthentheallianceofsocialistcountriesledbytheUSSR, andfightagainstdemocraticopposition.Thecreationofnewspecialservices wasalsoshown:theUOPandtheWSI.Thefocuswasonthenewtasksthat weresetfortheminconnectionwiththedemocraticchangesandnewalli- ances.TherewerepresentedspectacularUOPactions,whichcontributedto raisingtheprestigeofPolandontheinternationalarena. KEYWORDS *Correspondingauthor specialservices,politicalchanges,democracy,security ©2020byAuthor(s).ThisisanopenaccessarticleundertheCreativeCommonsAttribution -

Ivane Javakhishvili Tbilisi State University, Department of Sociological and Political Sciences

Ivane Javakhishvili Tbilisi State University, Department Of Sociological And Political Sciences Laura Kutubidze Main Social-Political Aspects of Georgian Press in 2000-2005 (Short version) Dissertation report for receiving academic degree - PH D. In Journalism Report is developed in Ivane Javakhishvili Tbilisi State University Scientific instructor, PH D. In Journalism, Professor Marina Vekua Tbilisi 2009 Content: Introduction; I chapter – Several General Specifications for Characterization of essence of Mass Media and Georgian Mass Media; About the Mass Communication and Mass Media; The General Specifications of Georgian Mass Media in Millennium; II chapter – Country from the Prism of Georgian Media; Image of the Country; West or Russia? (problematic aspects of State orientation); Several Aspects of the Topic of External Policy ; “Informational Guarantee” of Destabilization ; III chapter – Elections and the Political Spectrum; Elections of President, 2000 Year and Local Elections, 2002 Year; Permanent Election Regime, 2003 Year; Elections of Parliament and President, 2004 Year ; Elections in Post-revolution Adjara; IV chapter - “Rose Revolution” and Post-revolutionary Period; V chapter - Georgian Mass Media on the Visit of US President George Bush to Georgia; Conclusion; STATE. 2 Introduction The dissertation report mainly is based on printed media of 2000-2005, (newspapers – “Alia”, “Resonansi”, “24 Saati”, “Dilis Gazeti”, “Akhali Taoba”, “Kviris Palitra”, “Akhali Versia”, “Kviris Qronika”, “Georgian Times”, “Mtavari Gazeti”, -

Georgian Charter of Journalistic Ethics

Georgian Charter of Journalistic Ethics Study of the Media Coverage of the 2016 Parliamentary Elections TV News Monitoring Report 11 July – 30 August, 2016 The Georgian Charter of Journalistic Ethics is implementing the monitoring of TV news broadcasts within the framework of the project entitled “Study of the Media Coverage of the 2016 Parliamentary Elections” funded by the European Union (EU) and the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). The monitoring is carried out from 20 May to 19 December, 2016 and covers main news programs on the following 11 TV channels: “1st Channel” of the public broadcaster, “Rustavi 2”, “Maestro”, “GDS”, “Tabula”, “Kavkasia”, “TV Pirveli”, “Obieqtivi”, “Ajara TV”, and “TV 25”. The report covers the period from 11 July through 30 August 2016. The quantitative and the qualitative analysis of the monitoring data has revealed the following key findings: As during the previous round of monitoring, majority of TV channels most actively covered the activities of the government of Georgia (GoG). “Kavkasia” leads the list of the channels with favorable treatment of the Government’s activities with 18% of positive coverage. “Rustavi 2” is the most critical to the GoG with 72% of negative coverage and “GDS” – the most neutral, with 83% of neutral tone. “Kavkasia” revealed highest indicators (14%) of positive tone in connection with the President of Georgia. “Obieqtivi” was the most critical with 14% of negative tone and “Tabula” - the most neutral with 95% of neutral tone indicators. Activities of the “Georgian Dream” party were covered most favorably on “Imedi” (54% of positive tone indicators), and most negatively on “Rustavi 2” (52% of negative tone indicators). -

Gender and Society: Georgia

Gender and Society: Georgia Tbilisi 2008 The Report was prepared and published within the framework of the UNDP project - “Gender and Politics” The Report was prepared by the Institute for Policy Studies (IPS) The author: Nana Sumbadze For additional information refer to the office of the UNDP project “Gender and Politics” at the following address: Administrative building of the Parliament of Georgia, 8 Rustaveli avenue, room 034, Tbilisi; tel./fax (99532) 923662; www.genderandpolitics.ge and the office of the IPS, Chavchavadze avenue, 10; Tbilisi 0179; tel./fax (99532) 220060; e-mail: [email protected] The views expressed in this publication are those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of the United Nations or UNDP Editing: Sandeep Chakraborty Book design: Gio Sumbadze Copyright © UNDP 2008 All rights reserved Contents Acknowledgements 4 List of abbreviations 5 Preface 6 Chapter 1: Study design 9 Chapter 2: Equality 14 Gender in public realm Chapter 3: Participation in public life 30 Chapter 4: Employment 62 Gender in private realm Chapter 5: Gender in family life 78 Chapter 6: Human and social capital 98 Chapter 7: Steps forward 122 Bibliography 130 Annex I. Photo Voice 136 Annex II. Attitudes of ethnic minorities towards equality 152 Annex III. List of entries on Georgian women in Soviet encyclopaedia 153 Annex IV. List of organizations working on gender issues 162 Annex V. List of interviewed persons 173 Annex VI. List of focus groups 175 Acknowledgements from the Author The author would like to express her sincere gratitude to the staff of UNDP project “Gender and Politics” for their continuous support, and to Gender Equality Advisory Council for their valuable recommendations. -

David Usupashvili

David Usupashvili Chairman of the Parliament of Georgia David Usupashvili was elected as Chairman of the Parliament of Georgia on October 21, 2012. He has been Chairman of the Republican Party of Georgia (ALDE and LI member party) since 2005 and Deputy Chairman of the Political Coalition “Georgian Dream” since October 2011. David Usupashvili was born in Signagi, Georgia, on March 5, 1968. He graduated from Magaro Secondary School and continued education at IvaneJavakhishvili Tbilisi State University, where he obtained Diploma of Honours in Law (1985 - 1992). He received Master’s Degree in International Development Policy from Duke University, Terry Sanford Institute of Public Policy, USA (1997 - 1999). From 1999 to 2005 he worked for an USAID funded Rule of Law program, as Deputy Chief of Party and Senior Legal and Policy Advisor. During 2000 – 2001,David Usupashvili worked as an Executive Secretary for Anti-Corruption Working Group under President of Georgia. David Usupashvili was a founder of one of the first Georgian NGOs, Georgian Young Lawyers Associationthat promoted and largely contributed to democratization processes in Georgia. As a first Chairman he coordinated implementation of major rule of law programs (1994 - 1997). From 1992 to 1994 he worked for the President of Georgia as Senior Legal Adviser and Special Envoy of the President to Parliament and Constitutional Commission of Georgia. From 1989 to 1995 he served at the Central Election Commission of Georgia, as Chief Legal Consultant, Head of Legal Department and Member. David Usupashvili was a member of various boards of the leading Georgian NGOs such as GYLA, OSGF, TI, ISFED, ect. -

Public Opinion Survey Residents of Georgia

Public Opinion Survey Residents of Georgia May 20 – June 11, 2019 Detailed Methodology • The field work was carried out by Institute of Polling & Marketing. The survey was conducted by Dr. Rasa Alisauskiene of the public and market research company Baltic Surveys/The Gallup Organization on behalf of the International Republican Institute’s Center for Insights in Survey Research. • Data was collected throughout Georgia between May 20 and June 11, 2019, through face-to-face interviews at respondents’ home. • The sample consisted of 1,500 permanent residents of Georgia aged 18 or older and eligible to vote. It is representative of the general population by age, gender, region and size of the settlement. • A multistage probability sampling method was used with random route and next-birthday respondent selection procedures. • Stage one: All districts of Georgia are grouped into 10 regions. All regions of Georgia were surveyed (Tbilisi city – as separate region). • Stage two: Selection of the settlements – cities and villages. • Settlements were selected at random. The number of selected settlements in each region was proportional to the share of population living in a particular type of the settlement in each region. • Stage three: Primary sampling units were described. • The margin of error does not exceed plus, or minus 2.5 percent and the response rate was 68 percent. • The achieved sample is weighted for regions, gender, age, and urbanity. • Charts and graphs may not add up to 100 percent due to rounding. • The survey was funded by the -

![Download [Pdf]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1586/download-pdf-2311586.webp)

Download [Pdf]

This project is co-funded by the Seventh Framework Programme for Research and Technological Development of the European Union EU Grant Agreement number: 290529 Project acronym: ANTICORRP Project title: Anti-Corruption Policies Revisited Work Package: WP3, Corruption and governance improvement in global and continental perspectives Title of deliverable: D3.2.7. Background paper on Georgia Due date of deliverable: 28 February 2014 Actual submission date: 28 February 2014 Author: Andrew Wilson Editor: Alina Mungiu-Pippidi Organization name of lead beneficiary for this deliverable: Hertie School of Governance Project co-funded by the European Commission within the Seventh Framework Programme Dissemination Level PU Public X PP Restricted to other programme participants (including the Commission Services) RE Restricted to a group specified by the consortium (including the Commission Services) Co Confidential, only for members of the consortium (including the Commission Services) Georgia Background Report Andrew Wilson University College London January 2014 ABSTRACT Georgia had a terrible reputation for corruption, both in Soviet times and under the presidency of Eduard Shevardnadze (1992-2003). After the ‘Rose Revolution’ that led to Shevardnadze’s early resignation, many proclaimed that the government of new President Mikheil Saakashvili was a success story because of its apparent rapid progress in fighting corruption and promoting neo-liberal market reforms. His critics, however, saw only a façade of reform and a heavy hand in other areas, even before the war with Russia in 2008. Saakashvili’s second term (2008-13) was much more controversial – his supporters saw continued reform under difficult circumstances, his opponents only the consolidation of power. Under Saakashvili Georgia does indeed deserve credit for its innovative reforms that were highly successful in reducing ‘low-level’ corruption.