Ome

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bede's Ecclesiastical History of England a Revised

BEDE'S ECCLESIASTICAL HISTORY OF ENGLAND A REVISED TRANSLATION WITH INTRODUCTION, LIFE, AND NOTES BY A. M. SELLAR LATE VICE-PRINCIPAL OF LADY MARGARET HALL, OXFORD LONDON GEORGE BELL AND SONS 1907 EDITOR'S PREFACE The English version of the "Ecclesiastical History" in the following pages is a revision of the translation of Dr. Giles, which is itself a revision of the earlier rendering of Stevens. In the present edition very considerable alterations have been made, but the work of Dr. Giles remains the basis of the translation. The Latin text used throughout is Mr. Plummer's. Since the edition of Dr. Giles appeared in 1842, so much fresh work on the subject has been done, and recent research has brought so many new facts to light, that it has been found necessary to rewrite the notes almost entirely, and to add a new introduction. After the appearance of Mr. Plummer's edition of the Historical Works of Bede, it might seem superfluous, for the present at least, to write any notes at all on the "Ecclesiastical History." The present volume, however, is intended to fulfil a different and much humbler function. There has been no attempt at any original work, and no new theories are advanced. The object of the book is merely to present in a short and convenient form the substance of the views held by trustworthy authorities, and it is hoped that it may be found useful by those students who have either no time or no inclination to deal with more important works. Among the books of which most use has been made, are Mr. -

Historical Background to the Sculpture

CHAPTER II HISTORICAL BACKGROUND TO THE SCULPTURE THE AREA as do the rivers Don and its tributary the Dearne, further south. However, the county straddles the Pennines, so This volume completes the study of the sculpture of the that the upper reaches of the rivers Lune and Ribble, historic county of Yorkshire begun in volumes III (Lang draining away towards the west coast, are also within its 1991) and VI (Lang 2001) of the series: that is, it covers boundaries. the pre-1974 West Riding of Yorkshire. The geographical The effect of this topography on settlement is reflected spread of this area is in itself very important to the present in all phases of its history, as discussed below. Most study (Fig. 2). The modern county of West Yorkshire is dramatically and pertinently for our present purposes, it all to the east of Manchester, but the north-west corner is clear in the distribution of the Roman roads and the of the old West Riding curves round through the Pennine pre-Conquest sculpture, that both follow the river valleys dales to the north and west of Manchester, coming at yet avoid the low-lying marshy areas while keeping below one point to within a few miles of the west coast of the 300 metre mark. England. At the other end, it stretches a long way to the south, into what is now South Yorkshire. In fact, it touches on five other counties apart from the old North and POLITICAL SUMMARY East Ridings of Yorkshire: Lancashire, Cheshire, Derbyshire, Lincolnshire and Nottinghamshire. -

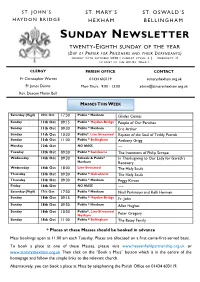

Sunday Newsletter

ST. JOHN’S ST. MARY’S ST. OSWALD’S HAYDON BRIDGE H E X H A M BELLINGHAM SUNDAY NEWSLETTER TWENTY-EIGHTH SUNDAY OF THE YEAR (DAY OF PRAYER FOR PRISONERS AND THEIR DEPENDANTS) SUNDAY 11TH OCTOBER 2020 | SUNDAY CYCLE: A | WEEKDAYS: II LITURGY OF THE HOURS: WEEK 1 CLERGY PARISH OFFICE CONTACT Fr Christopher Warren 01434 603119 stmaryshexham.org.uk Fr James Dunne Mon-Thurs. 9:00 - 13:00 [email protected] Rev. Deacon Martin Bell MASSES THIS WEEK Saturday (Vigil) 10th Oct 17:30 Public * Hexham Gladys Coates Sunday 11th Oct 09:15 Public * Haydon Bridge People of Our Parishes Sunday 11th Oct 09:30 Public * Hexham Eric Arthur Sunday 11th Oct 10:30 Public*, Live-Streamed Repose of the Soul of Teddy Patrick Sunday 11th Oct 11:00 Public * Bellingham Anthony Grigg Monday 12th Oct NO MASS — Tuesday 13th Oct 09:30 Public * Swinburne The Intentions of Philip Scrope Wednesday 14th Oct 09:30 Schools & Public* In Thanksgiving to Our Lady for Gareth’s Hexham Recovery Wednesday 14th Oct 18:00 Live-Streamed The Holy Souls Thursday 15th Oct 09:30 Public * Haltwhistle The Holy Souls Thursday 15th Oct 09:30 Public * Hexham Peggy Kirvan Friday 16th Oct NO MASS —- Saturday (Vigil) 17th Oct 17:30 Public * Hexham Niall Parkinson and Kelli Herman Sunday 18th Oct 09:15 Public * Haydon Bridge Fr. John Sunday 18th Oct 09:30 Public * Hexham Allan Hughes Sunday 18th Oct 10:30 Public*, Live-Streamed Hexham Peter Gregory Sunday 18th Oct 11:00 Public * Bellingham The Batey Family * Places at these Masses should be booked in advance Mass bookings open at 11:00 am each Tuesday. -

INDEX 265 © in This Web Service Cambridge

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-73073-0 - The Cambridge Companion to Bede Edited by Scott DeGregorio Index More information INDEX Aachen, Council of 193 Aldhelm 49–52, 80, 100, 101, 225 Abercorn 58 De uirginitate 50–1 Acca, bishop of Hexham 4, 11, 54, 62, 129, Enigmata 50 145, 146, 176, 178, 203 letters 16, 75 active life 110, 111, 152, 153 Alfred, king of Wessex 10, 217, 218, 219, 220, Adamnan, Abbot 60, 156 221, 224, 225, 236, 237 Adomnán, abbot of Iona 10, 73, 76, 78 Alhfrith, Deiran sub-king 73 On the Holy Places 82, 115, 222 Ambrose 104, 114, 115, 149 Ælfric 168, 216, 217, 220, 221, 224, 225–7, Ammianus Marcellinus 171 237, 238 Angles 27, 28 Aelle, king of Sussex 27 Anglo-Saxon Chronicle 3, 29, 32, 216, Ælle, King 234 220, 238 Æthelbald, king of Mercia 27, 28 Aquinas, Thomas, Saint 231 Æthelberht, king of Kent 27, 185 Arator 46, 106, 145 Æthelbert 110, 177 Arbeia, Roman fort at 92 Æthelburh, daughter of King Æthelberht 55, Arculf, Bishop 10 56, 223 Asser 218, 219, 221, 237 Æthelfrith, king of Northumbria 26, 33, 36, Athanasius, Saint 52, 172, 182 69, 70, 177 Life of Saint Antony 52, 172, 173, 182 Æthelstan, King 218 Augustine, archbishop of Canterbury 21, Æthelthryth 62, 221 35–6, 76, 150, 156, 185, 222 Æthelwold, archbishop of Canterbury 225 mission of 36, 48, 80 Æthelwold, bishop of Lindisfarne 54 Augustine, bishop of Hippo 43, 44, 45, 80, Æthelwulf 64 104, 115, 123, 132, 133, 144, 145, On the Abbots 60, 64 152, 166, 231 Agatho, Pope 84, 102 and biblical interpretation 143, 147, Agilbert, bishop of the West Saxons 161 148, -

Lives of the British Saints

LIVES OF THE BRITISH SAINTS Vladimir Moss Copyright: Vladimir Moss, 2009 1. SAINTS ACCA AND ALCMUND, BISHOPS OF HEXHAM ......................5 2. SAINT ADRIAN, ABBOT OF CANTERBURY...............................................8 3. SAINT ADRIAN, HIEROMARTYR BISHOP OF MAY and those with him ....................................................................................................................................9 4. SAINT AIDAN, BISHOP OF LINDISFARNE...............................................11 5. SAINT ALBAN, PROTOMARTYR OF BRITAIN.........................................16 6. SAINT ALCMUND, MARTYR-KING OF NORTHUMBRIA ....................20 7. SAINT ALDHELM, BISHOP OF SHERBORNE...........................................21 8. SAINT ALFRED, MARTYR-PRINCE OF ENGLAND ................................27 9. SAINT ALPHEGE, HIEROMARTYR ARCHBISHOP OF CANTERBURY ..................................................................................................................................30 10. SAINT ALPHEGE “THE BALD”, BISHOP OF WINCHESTER...............41 11. SAINT ASAPH, BISHOP OF ST. ASAPH’S ................................................42 12. SAINTS AUGUSTINE, LAURENCE, MELLITUS, JUSTUS, HONORIUS AND DEUSDEDIT, ARCHBISHOPS OF CANTERBURY ..............................43 13. SAINTS BALDRED AND BALDRED, MONKS OF BASS ROCK ...........54 14. SAINT BATHILD, QUEEN OF FRANCE....................................................55 15. SAINT BEDE “THE VENERABLE” OF JARROW .....................................57 16. SAINT BENIGNUS (BEONNA) -

Expressions of Personal Autonomy, Authority, and Agency in Early Anglo- Saxon Monasticism William Tanner Smoot [email protected]

Marshall University Marshall Digital Scholar Theses, Dissertations and Capstones 2017 In the Company of Angels: Expressions of Personal Autonomy, Authority, and Agency in Early Anglo- Saxon Monasticism William Tanner Smoot [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://mds.marshall.edu/etd Part of the European History Commons, and the History of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Smoot, William Tanner, "In the Company of Angels: Expressions of Personal Autonomy, Authority, and Agency in Early Anglo-Saxon Monasticism" (2017). Theses, Dissertations and Capstones. 1094. http://mds.marshall.edu/etd/1094 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Marshall Digital Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses, Dissertations and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Marshall Digital Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. IN THE COMPANY OF ANGELS: EXPRESSIONS OF PERSONAL AUTONOMY, AUTHORITY, AND AGENCY IN EARLY ANGLO-SAXON MONASTICISM A thesis submitted to The Graduate College of Marshall University In partial fulfillment of The requirements for the degree of Master of Arts In History by William Tanner Smoot Approved by Dr. Laura Michele Diener, Committee Chairperson Dr. William Palmer Dr. Michael Woods Marshall University May 2017 ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank all of those who helped and supported me in the process of writing and completing this thesis. I want to thank specifically my family and friends for their inexhaustible support, as well as the faculty of the history department of Marshall University for their constant guidance and advice. I finally would like to particularly thank Dr. -

"The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle" (Everyman Press, London, 1953, 1972)

"The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle " ****The Project Gutenberg Etext of The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle**** Translated by James Ingram Copyright laws are changing all over the world, be sure to check the copyright laws for your country before posting these files!! Please take a look at the important information in this header. We encourage you to keep this file on your own disk, keeping an electronic path open for the next readers. Do not remove this. **Welcome To The World of Free Plain Vanilla Electronic Texts** **Etexts Readable By Both Humans and By Computers, Since 1971** *These Etexts Prepared By Hundreds of Volunteers and Donations* Information on contacting Project Gutenberg to get Etexts, and further information is included below. We need your donations. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle Translated by James Ingram September, 1996 [Etext #657] ****The Project Gutenberg Etext of The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle**** *****This file should be named angsx10.txt or angsx10.zip****** Corrected EDITIONS of our etexts get a new NUMBER, angsx11.txt. VERSIONS based on separate sources get new LETTER, angsx10a.txt. We are now trying to release all our books one month in advance of the official release dates, for time for better editing. Please note: neither this list nor its contents are final till midnight of the last day of the month of any such announcement. The official release date of all Project Gutenberg Etexts is at Midnight, Central Time, of the last day of the stated month. A preliminary version may often be posted for suggestion, comment and editing by those who wish to do so. -

The Way of Light

The Way of Light Heavenfield - Hexham - Durham (linking to St Oswald’s Way) Heavenfield – Acomb – Hexham – Dipton Mill – Newbiggin The Christian – Ordley – Devil’s Water – Slaley Forest – Blanchland Moor – Blanchland – Edmundbyers – Muggleswick – Derwent crossroads of Gorge – Castleside – Lanchester – Quebec – Ushaw the British Isles College – Witton Gilbert – Durham Cathedral Distance: 45 miles/72km The Way of Light its Christianisation. It proceeds via historic Hexham and its But settlements are few and far between on this route. abbey, and pauses alongside one of the most wondrous What impresses just as much are the fabulous, far-reaching Welcome to a breath-taking trail that transports testimonies to Catholic faith ever built in Northern England, views from the valleys, forests and fells that form the finest you from the dawn of Christianity through to one-time seminary Ushaw College, a glamorous ensemble of upland scenery on any of the six Northern Saints Trails. contemporary pilgrimage, via Dark Ages battles Gothic Revival edifices, chapels and gardens. Like a guiding light at journey’s end is Durham Cathedral, that changed a region’s faith, abbeys that matched with St Cuthbert’s Shrine, but also 12th century wall Rome for majesty and a stunning seminary that paintings depicting St Oswald opposite St Cuthbert. For taught England ’s leading ecclesiastics. whilst the latter’s cult might have given rise to the cathedral, without the former the North East’s Golden Age and pivotal The remote Way of Light provides a larger-than-life role in the spread of Christianity may never have come low-down on Christianity’s illustrious history in the North about at all. -

The History of St. Patrick's RC Church, Felling 1895

The History of St. Patrick’s RC Church, Felling 1895 - 2014 Tom R Sterling The History of St. Patrick’s RC Church, Felling 1895 - 2014 High Street Felling Gateshead Tyne & Wear NE10 9LT www.stpatricks-felling.co.uk 1 Copyright © 2014 No part of this publication may be reproduced without the written permission of the Parish Priest of St. Patrick’s Church, Felling. The Diocese of Hexham and Newcastle is a Company limited by guarantee Registered in England Number 7732977 Registered Charity No: 1143450 2 Acknowledgements I would like to pay tribute to the late Peter Haywood and to the members of the Centenary committee who assisted in the compilation of A History of St. Patrick’s Church, Felling 1895 - 1995, which is copied in its entirety in Chapter 1. To Anne Bradley for providing the information for Chapter 2 by researching 19 years of newsletters 1995 – 2014, to Norman Dunn for providing some of the historical images from his web site www.gatesheadeast.co.uk, to Fr. Ian Patterson for his assistance and to all the parishioners of St. Patrick’s Church for the historical images and memorabilia. Tom R. Sterling 3 Introduction The elegant stone staircase, built in the Romanesque style, which leads to the processional entrance at the front of St. Patrick’s Church suffered damage caused by the passage of time. Severe water ingress led to structural damage rendering the staircase unsafe to use. Following an application to the Heritage Lottery Fund, a grant of almost £90,000 was obtained to assist in restoring it back to its original beauty. -

Due out in Cities, Saints, and Scholars in Early Medieval Europe. Essays in Honour of Alan Thacker, Ed

CEADWALLA AND WILFRID 1 Due out in Cities, Saints, and Scholars in Early Medieval Europe. Essays in honour of Alan Thacker, ed. S. deGregorio & P. J. E. Kershaw (Turnhout: Brepols). King Ceadwalla and Bishop Wilfrid Richard Sharpe The short career of King Ceadwalla in Wessex was a bloody business, perhaps right up to the point when he left England for Rome, where he was baptized by Pope Sergius on Holy Saturday, 10 April 689. Ten days later he was buried at St Peter’s basilica, and Bede would publish his Roman epitaph.1 Was this a great success-story for the Christian mission, a triumphant conversion, crowned by baptism at the hands of the pope and unblemished death in the white surplice of baptism? William of Malmesbury and Henry of Huntingdon in the twelfth century, both of them reading Bede as their chief witness, interpreted Ceadwalla’s career in a heroic light.2 They saw his life through his death in albis in Rome. Such a reading has endured. In commenting on his gifts of land made to churches, Dorothy Whitelock wrote, ‘At the time when Ceadwalla made these grants he had not yet been baptized, but this was not out of hostility to the Christian faith, but because he wished his baptism to take place in Rome’.3 Ceadwalla was not hostile to 1 Bede, HE V 7; G. B. de Rossi, Inscriptiones Christianae Vrbis Romae, 2 vols (Rome, 1857–61, 1888), ii. 288–9; R. Sharpe, ‘King Ceadwalla’s Roman epitaph’, in Latin Learning and English Lore. Papers for Michael Lapidge (Toronto, 2005), i. -

Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-49035-1 — the Afterlife of St Cuthbert Christiania Whitehead Index More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-49035-1 — The Afterlife of St Cuthbert Christiania Whitehead Index More Information Index Aardenberg, 95–97 Benedictional of, 46 Abbot of Seez, 71 Aethilwald, Farne hermit, 15, 32 Aberdeen, 263 Aethilwulf, De abbatibus, 241 Abraham, 150, 161 Agincourt, Battle of, 177 Acca, St, Bishop of Hexham, 24, 55, 213 Aidan, St, Bishop of Lindisfarne, 13, 14, 17, 30, 33, Aclyff, John, Prior of Coldingham, 190 37, 38, 53, 67, 127, 132, 176, 179, 217, 270, Ada de Warenne, Countess, 87 288, 296 Adomnán, St, Abbot of Iona, 14, 17, 128, 129, 135 relics of, 13, 14, 35, 55, 65, 71 De locis sanctis, 17 Vita of, 126, 250, 253, 268, 269, 287 Vita of, 129, 135 Aird, William, 50, 52 Vita Sancti Columbae, 17–18, 22, 29, 57, 81, 125, Alchmund, St, Bishop of Hexham, 55, 213 240, 253 Alcuin of York, 21, 34 Aebbe, St, Abbess of Coldingham, 55, 179, 213, Aldan, Bishop of Whithorn, 128, 130 246, 257 Aldfrith, King of Northumbria, 13, 17 Vita of, 126, 158, 287 See also, Reginald of Aldhelm of Malmesbury, 21 Durham Alexander, Dominic, 4, 84, 106, 119, 122, 253 Aelfflaed, Abbess of Whitby, 18, 28, 61, 112, 239 Alexander, King of Scotland, 73 Aelfric, 6 Alfred the Great, King, 6, 42–44, 45, 68, 82, 180, Aelle, King of Northumbria, 35, 39 181, 183–184, 185–186, 201, 230, 294 See also, Aelred, St, Abbot of Rievaulx, 78, 87, 100, 102, Cuthbert, St, relation to King Alfred 180, 229, 253, 255, 256 Alliterative Morte Arthure, 201 De genealogia regum Anglorum, 242, 253 Alnwick Castle, 192 De institutione inclusarum, 102, 122 Ancrene Wisse, 122, -

Bede's Ecclesiastical History of England

Bede©s Ecclesiastical History of England by The Venerable Bede About Bede©s Ecclesiastical History of England by The Venerable Bede Title: Bede©s Ecclesiastical History of England URL: http://www.ccel.org/ccel/bede/history.html Author(s): Bede, St. ("The Venerable," c. 673-735) (Translator) Print Basis: London: George Bell and Sons, 1907 Source: Rights: Public Domain Date Created: 2000-07-25 CCEL Subjects: All; History; Classic LC Call no: BR746 LC Subjects: Christianity History By Region or Country Bede©s Ecclesiastical History of England The Venerable Bede Table of Contents About This Book. p. ii Title Page. p. 1 Preface. p. 2 Introduction. p. 3 Life of Bede. p. 10 The Ecclesiastical History of the English Nation. p. 16 Book I. p. 16 I. Of the Situation of Britain and Ireland, and of their ancient inhabitants. p. 16 II. How Caius Julius Caesar was the first Roman that came into Britain. [54 AD]. p. 18 III. How Claudius, the second of the Romans who came into Britain, brought the islands Orcades. p. 19 IV. How Lucius, king of Britain, writing to Pope Eleutherus, desired to be made a Christian.. p. 19 V. How the Emperor Severus divided from the rest by a rampart that part of Britain which had been recovered. p. 19 VI. Of the reign of Diocletian, and how he persecuted the Christians. [286 AD]. p. 20 VIII. How, when the persecution ceased, the Church in Britain enjoyed peace till the time of the . p. 21 IX. How during the reign of Gratian, Maximus, being created Emperor in Britain, returned into Gaul with a mighty army.