Heterotrophic Plasticity and Resilience And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Evidence from the Polypipapiliotrematinae N

Accepted Manuscript Intermediate host switches drive diversification among the largest trematode family: evidence from the Polypipapiliotrematinae n. subf. (Opecoelidae), par- asites transmitted to butterflyfishes via predation of coral polyps Storm B. Martin, Pierre Sasal, Scott C. Cutmore, Selina Ward, Greta S. Aeby, Thomas H. Cribb PII: S0020-7519(18)30242-X DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpara.2018.09.003 Reference: PARA 4108 To appear in: International Journal for Parasitology Received Date: 14 May 2018 Revised Date: 5 September 2018 Accepted Date: 6 September 2018 Please cite this article as: Martin, S.B., Sasal, P., Cutmore, S.C., Ward, S., Aeby, G.S., Cribb, T.H., Intermediate host switches drive diversification among the largest trematode family: evidence from the Polypipapiliotrematinae n. subf. (Opecoelidae), parasites transmitted to butterflyfishes via predation of coral polyps, International Journal for Parasitology (2018), doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpara.2018.09.003 This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain. Intermediate host switches drive diversification among the largest trematode family: evidence from the Polypipapiliotrematinae n. subf. (Opecoelidae), parasites transmitted to butterflyfishes via predation of coral polyps Storm B. Martina,*, Pierre Sasalb,c, Scott C. -

Metagenomic Analysis Indicates That Stressors Induce Production of Herpes-Like Viruses in the Coral Porites Compressa

Metagenomic analysis indicates that stressors induce production of herpes-like viruses in the coral Porites compressa Rebecca L. Vega Thurbera,b,1, Katie L. Barotta, Dana Halla, Hong Liua, Beltran Rodriguez-Muellera, Christelle Desnuesa,c, Robert A. Edwardsa,d,e,f, Matthew Haynesa, Florent E. Anglya, Linda Wegleya, and Forest L. Rohwera,e aDepartment of Biology, dComputational Sciences Research Center, and eCenter for Microbial Sciences, San Diego State University, San Diego, CA 92182; bDepartment of Biological Sciences, Florida International University, 3000 North East 151st, North Miami, FL 33181; cUnite´des Rickettsies, Unite Mixte de Recherche, Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique 6020. Faculte´deMe´ decine de la Timone, 13385 Marseille, France; and fMathematics and Computer Science Division, Argonne National Laboratory, Argonne, IL 60439 Communicated by Baruch S. Blumberg, Fox Chase Cancer Center, Philadelphia, PA, September 11, 2008 (received for review April 25, 2008) During the last several decades corals have been in decline and at least established, an increase in viral particles within dinoflagellates has one-third of all coral species are now threatened with extinction. been hypothesized to be responsible for symbiont loss during Coral disease has been a major contributor to this threat, but little is bleaching (25–27). VLPs also have been identified visually on known about the responsible pathogens. To date most research has several species of scleractinian corals, specifically: Acropora muri- focused on bacterial and fungal diseases; however, viruses may also cata, Porites lobata, Porites lutea, and Porites australiensis (28). Based be important for coral health. Using a combination of empirical viral on morphological characteristics, these VLPs belong to several viral metagenomics and real-time PCR, we show that Porites compressa families including: tailed phages, large filamentous, and small corals contain a suite of eukaryotic viruses, many related to the (30–80 nm) to large (Ͼ100 nm) polyhedral viruses (29). -

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material SM1. Post-Processing of Images for Automated Classification Imagery was collected without artificial light and using a fisheye lens to maximise light capture, therefore each image needed to be processed prior annotation in order to balance colour and to minimise the non-linear distortion introduced by the fisheye lens (Figure S1). Initially, colour balance and lenses distortion correction were manually applied on the raw images using Photoshop (Adobe Systems, California, USA). However, in order to optimize the manual post-processing time of thousands of images, more recent images from the Indian Ocean and Pacific Ocean were post- processed using compressed images (jpeg format) and an automatic batch processing in Photoshop and ImageMagick, the latter an open-source software for image processing (www.imagemagick.org). In view of this, the performance of the automated image annotation on images without colour balance was contrasted against images colour balanced using manual post-processing (on raw images) and the automatic batch processing (on jpeg images). For this evaluation, the error metric described in the main text (Materials and Methods) was applied to the images from following regions: the Maldives and the Great Barrier Reef (Figures S2 and S3). We found that the colour balance applied regardless the type of processing (manual vs automatic) had an important beneficial effect on the performance of the automated image annotation as errors were reduced for critical labels in both regions (e.g., Algae labels; Figures S2 and S3). Importantly, no major differences in the performance of the automated annotations were observed between manual and automated adjustments for colour balance. -

Hawai'i Institute of Marine Biology Northwestern Hawaiian Islands

Hawai‘i Institute of Marine Biology Northwestern Hawaiian Islands Coral Reef Research Partnership Quarterly Progress Reports II-III August, 2005-March, 2006 Report submitted by Malia Rivera and Jo-Ann Leong April 21, 2006 Photo credits: Front cover and back cover-reef at French Frigate Shoals. Upper left, reef at Pearl and Hermes. Photos by James Watt. Hawai‘i Institute of Marine Biology Northwestern Hawaiian Islands Coral Reef Research Partnership Quarterly Progress Reports II-III August, 2005-March, 2006 Report submitted by Malia Rivera and Jo-Ann Leong April 21, 2006 Acknowledgments. Hawaii Institute of Marine Biology (HIMB) acknowledges the support of Senator Daniel K. Inouye’s Office, the National Marine Sanctuary Program (NMSP), the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands Coral Reef Ecosystem Reserve (NWHICRER), State of Hawaii Department of Land and Natural Resources (DLNR) Division of Aquatic Resources, US Fish and Wildlife Service, NOAA Fisheries, and the numerous University of Hawaii partners involved in this project. Funding provided by NMSP MOA 2005-008/66832. Photos provided by NOAA NWHICRER and HIMB. Aerial photo of Moku o Lo‘e (Coconut Island) by Brent Daniel. Background The Hawai‘i Institute of Marine Biology (School of Ocean and Earth Science and Technology, University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa) signed a memorandum of agreement with National Marine Sanctuary Program (NOS, NOAA) on March 28, 2005, to assist the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands Coral Reef Ecosystem Reserve (NWHICRER) with scientific research required for the development of a science-based ecosystem management plan. With this overriding objective, a scope of work was developed to: 1. Understand the population structures of bottomfish, lobsters, reef fish, endemic coral species, and adult predator species in the NWHI. -

Genetic Structure Is Stronger Across Human-Impacted Habitats Than Among Islands in the Coral Porites Lobata

Genetic structure is stronger across human-impacted habitats than among islands in the coral Porites lobata Kaho H. Tisthammer1,2, Zac H. Forsman3, Robert J. Toonen3 and Robert H. Richmond1 1 Kewalo Marine Laboratory, University of Hawaii at Manoa, Honolulu, HI, United States of America 2 Department of Biology, San Francisco State University, San Francisco, CA, United States of America 3 Hawaii Institute of Marine Biology, University of Hawaii at Manoa, Kaneohe, HI, United States of America ABSTRACT We examined genetic structure in the lobe coral Porites lobata among pairs of highly variable and high-stress nearshore sites and adjacent less variable and less impacted offshore sites on the islands of O‘ahu and Maui, Hawai‘i. Using an analysis of molecular variance framework, we tested whether populations were more structured by geographic distance or environmental extremes. The genetic patterns we observed followed isolation by environment, where nearshore and adjacent offshore populations showed significant genetic structure at both locations (AMOVA FST D 0.04∼0.19, P < 0:001), but no significant isolation by distance between islands. Strikingly, corals from the two nearshore sites with higher levels of environmental stressors on different islands over 100 km apart with similar environmentally stressful conditions were genetically closer (FST D 0.0, P D 0.73) than those within a single location less than 2 km apart (FST D 0.04∼0.08, P < 0:01). In contrast, a third site with a less impacted nearshore site (i.e., less pronounced environmental gradient) showed no significant structure from the offshore comparison. Our results show much stronger support for environment than distance separating these populations. -

Update: Coral Bleaching Data 1 0 / 1 3 / 2 0 1 4

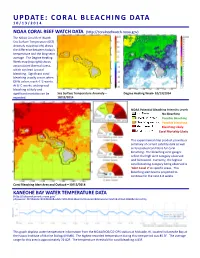

UPDATE: CORAL BLEACHING DATA 1 0 / 1 3 / 2 0 1 4 NOAA CORAL REEF WATCH DATA (http://coralreefwatch.noaa.gov) The NOAA Coral Reef Watch Sea Surface Temperature (SST) Anomaly map (top left) shows the difference between today's temperature and the long-term average. The Degree Heating Week map (top right) shows accumulated thermal stress, which can lead to coral bleaching. Significant coral bleaching usually occurs when DHW values reach 4 °C-weeks. At 8 °C-weeks, widespread bleaching is likely and significant mortality can be Sea Surface Temperature Anomaly— Degree Heating Week- 10/13/2014 expected. 10/13/2014 NOAA Potential Bleaching Intensity Levels No bleaching Possible bleaching Possible bleaching Bleaching Likely Coral Mortality Likely This experimental map product provides a summary of current satellite data as well as forecasted conditions for coral bleaching. The bleaching alert gauges reflect the high alert category observed and forecasted. Currently, the highest coral bleaching category being observed is ‘Alert Level 2’ in specific areas. This bleaching alert level is projected to continue for the next 4-8 weeks. Coral Bleaching Alert Area and Outlook—10/13/2014 KANEOHE BAY WATER TEMPERATURE DATA (http://tidesandcurrents.noaa.gov/ physocean.htmlbdate=20140929&edate=20141013&units=standard&timezone=GMT&id=1612480&interval=6) This graph displays water temperature information from the NOAA/NOS/CO-OPS station at Mokuole, HI, located in Kaneohe Bay at the Hawaii Institute of Marine Biology (HIMB). The highest recorded temperature during this time period was 85.3F. The average range for this area is approximately 72-82F. The temperature threshold for coral bleaching is 83F. -

Reproduction and Population of Porites Divaricata at Rodriguez Key: the Lorf Ida Keys, USA John Mcdermond Nova Southeastern University, [email protected]

Nova Southeastern University NSUWorks HCNSO Student Theses and Dissertations HCNSO Student Work 1-1-2014 Reproduction and Population of Porites divaricata at Rodriguez Key: The lorF ida Keys, USA John McDermond Nova Southeastern University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://nsuworks.nova.edu/occ_stuetd Part of the Marine Biology Commons, and the Oceanography Commons Share Feedback About This Item NSUWorks Citation John McDermond. 2014. Reproduction and Population of Porites divaricata at Rodriguez Key: The Florida Keys, USA. Master's thesis. Nova Southeastern University. Retrieved from NSUWorks, Oceanographic Center. (17) https://nsuworks.nova.edu/occ_stuetd/17. This Thesis is brought to you by the HCNSO Student Work at NSUWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in HCNSO Student Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of NSUWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NOVA SOUTHEASTERN UNIVERSITY OCEANOGRAPHIC CENTER Reproduction and Population of Porites divaricata at Rodriguez Key: The Florida Keys, USA By: John McDermond Submitted to the faculty of Nova Southeastern University Oceanographic Center in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science with a specialty in Marine Biology Nova Southeastern University i Thesis of John McDermond Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Masters of Science: Marine Biology Nova Southeastern University Oceanographic Center Major Professor: __________________________________ -

Red Fluorescent Protein Responsible for Pigmentation in Trematode-Infected Porites Compressa Tissues

Reference: Biol. Bull. 216: 68–74. (February 2009) © 2009 Marine Biological Laboratory Red Fluorescent Protein Responsible for Pigmentation in Trematode-Infected Porites compressa Tissues CAROLINE V. PALMER*,1,2, MELISSA S. ROTH3, AND RUTH D. GATES Hawai’i Institute of Marine Biology, University of Hawai’i at Manoa P.O. Box 1346, Kaneohe, Hawaii 96744 Abstract. Reports of coral disease have increased dramat- INTRODUCTION ically over the last decade; however, the biological mecha- nisms that corals utilize to limit infection and resist disease A more comprehensive understanding of resistance remain poorly understood. Compromised coral tissues often mechanisms in corals is a critical component of the knowl- display non-normal pigmentation that potentially represents edge base necessary to design strategies aimed at mitigating an inflammation-like response, although these pigments re- the increasing incidence of coral disease (Peters, 1997; main uncharacterized. Using spectral emission analysis and Harvell et al., 1999, 2007; Hoegh-Guldberg, 1999; Suther- cryo-histological and electrophoretic techniques, we inves- land et al., 2004; Aeby, 2006) associated with reduced water tigated the pink pigmentation associated with trematodiasis, quality (Bruno et al., 2003) and ocean warming (Harvell et al., infection with Podocotyloides stenometre larval trematode, 2007). Disease resistance mechanisms in invertebrates are primarily limited to the innate immune system, which in Porites compressa. Spectral emission analysis reveals provides immediate, effective, and nonspecific internal de- that macroscopic areas of pink pigmentation fluoresce under fense against invading organisms via a series of cellular blue light excitation (450 nm) and produce a broad emission pathways (Rinkevich, 1999; Cooper, 2002; Cerenius and peak at 590 nm (Ϯ6) with a 60-nm full width at half So¨derha¨ll, 2004). -

2015 Coral Bleaching Surveys: South Kohala, North Kona © David Slater

! Summary of Findings 2015 Coral Bleaching Surveys: South Kohala, North Kona © David Slater What is Coral Bleaching? Coral bleaching is a stress response caused by the breakdown of the symbiotic relationship between the coral and the algae (zooxanthellae) that live inside its tissues. When the coral expels these algae the coral skeleton becomes visible, giving it a pale or “bleached” appearance. Mass bleaching events have been linked with mounting thermal stress associated with a warming planet and seas and are expected to continue increasing in severity, geographic extent, and frequency. Although some species and individual coral colonies can withstand more stress than others, corals will eventually die if the stressor © TNC does not abate and the symbiosis is not reestablished. Bleached Pocillopora eydouxi, Oct, 2015. Coral Bleaching in Hawai‘i Prompted by rising sea surface temperatures south of the Main Hawaiian Islands (MHI) in June 2015, NOAA’s Coral Reef Watch Program issued a bleaching warning for the MHI. By October 2015, the agency confirmed that West Hawai‘i Island experienced the most severe thermal stress in the MHI for 18.35 consecutive weeks (Fig. 1). Following the first report of bleached coral from a Puakō Makai Watch volun- teer snorkeling at Paniau, scientists from The Nature Conservancy, NOAA’s Coral Reef Ecosystem Program (CREP), and Hawai‘i's Division of Aquatic Resources (DAR) conducted four weeks of field surveys to assess the damage. The team surveyed more than 14,000 coral colonies across the South Kohala and North Kona regions of West Hawai’i, assessing the incidence (proportion of coral colonies that bleached) and severity of bleaching of each colony. -

Population Structure and Clonal Prevalence of Scleractinian Corals (Montipora Capitata and Porites Compressa) in Kaneohe Bay, Oa

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2019.12.11.860585; this version posted December 12, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY 4.0 International license. 1 1 Population structure and clonal prevalence of scleractinian corals (Montipora capitata and 2 Porites compressa) in Kaneohe Bay, Oahu 3 4 5 Locatelli NS¹* and JA Drew² 6 7 8 ¹ Columbia University, Department of Ecology, Evolution, and Environmental Biology, New 9 York, NY 10 ² SUNY College of Environmental Science and Forestry, Syracuse, NY 11 12 13 * Corresponding author: Nicolas S. Locatelli 14 Email: [email protected] 15 Address: Columbia University 16 Department of Ecology, Evolution, and Environmental Biology 17 10th Floor Schermerhorn Extension 18 1200 Amsterdam Avenue 19 New York, NY 10027 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2019.12.11.860585; this version posted December 12, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY 4.0 International license. 2 20 Abstract 21 As the effects of anthropogenic climate change grow, mass coral bleaching events are expected to 22 increase in severity and extent. Much research has focused on the environmental stressors 23 themselves, symbiotic community compositions, and transcriptomics of the coral host. Globally, 24 fine-scale population structure of corals is understudied. -

Microbial Aggregates Within Tissues Infect a Diversity of Corals Throughout the Indo-Pacific

Vol. 500: 1–9, 2014 MARINE ECOLOGY PROGRESS SERIES Published March 17 doi: 10.3354/meps10698 Mar Ecol Prog Ser FREEREE ACCESSCCESS FEATURE ARTICLE Microbial aggregates within tissues infect a diversity of corals throughout the Indo-Pacific Thierry M. Work1,2,*, Greta S. Aeby2 1US Geological Survey, National Wildlife Health Center, Honolulu Field Station, PO Box 50167, Honolulu, Hawaii, USA 2Hawaii Institute of Marine Biology, PO Box 1346, Kane‘ohe, Hawaii, USA ABSTRACT: Coral reefs are highly diverse eco - systems where symbioses play a pivotal role. Corals contain cell-associated microbial aggregates (CAMA), yet little is known about how widespread they are among coral species or the nature of the symbio tic re- lationship. Using histology, we found CAMA within 24 species of corals from 6 genera from Hawaii, American Samoa, Palmyra, Johnston Atoll, Guam, and Australia. Prevalence (%) of infection varied among coral genera: Acropora, Porites, and Pocillo- pora were commonly infected whereas Montipora were not. Acropora from the Western Pacific were significantly more likely to be infected with CAMA than those from the Central Pacific, whereas the re- verse was true for Porites. Compared with apparently healthy colonies, tissues from diseased colonies were Microscopic bacteria in tissues of coral polyps are important significantly more likely to have both surface and to coral health, ecology, and possibly evolution. basal body walls infected. The close association of Illustration: Thierry M. Work CAMA with host cells in numerous species of appar- ently healthy corals and lack of associated cell patho- logy reveals an intimate agent− host association. Fur- thermore, CAMA are Gram negative and in some corals may be related to chla mydia or rickettsia. -

The Revolution of Science Through Scuba

The Revolution of Science through Scuba Scuba Revolutionizes Marine Science Jon D. Witman, Paul K. Dayton, Suzanne N. Arnold, Robert S. Steneck, and Charles Birkeland ABSTRACT. Scuba provides scientists with the capacity for direct observation and experimental manipulation in underwater research. Technology allows broader- scale observations and measure- ments such as satellite detection of coral bleaching up to a global scale and LIDAR determination of reef- wide topographic complexity on landscape to regional scales. Scuba- based observations provide a means of ground truthing these broad-scale technologies. For example, ground truthing the read- ings on a scale as small as a video transect taken at 50 cm above the substratum can reveal that the previously confident interpretation of the transect data from the video analysis was inaccurate. At the opposite end of the spatial continuum, electron microscopy and DNA analysis provide the ca- pacity to determine species traits at a scale too fine for direct observation, while observations made during the collection of samples by scuba can provide vital information on the context of the tissue sample collection. Using our hands and eyes to set up experiments under water is less expensive and more adaptable to the unexpected topographic complexities of hard substratum habitats than doing so with submersibles, robots, or via cables from ships. The most profound contribution of scuba to underwater science, however, is the otherwise unobtainable insights provided by direct observation. Ecology is not always predictable from species traits because the behavioral or interactive charac- teristics of marine organisms together cause them to function in surprising and often synergistic ways.