Hidden Seed and Harvest : a History of the Moravians

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2021 Wachovia Historical Society 125Th Annual Meeting—Oct

WT The Wachovia Tract WT A Publication of the Wachovia Historical Society Volume 21, Issue 1 Spring 2021 Wachovia Historical Society 125th Annual Meeting—Oct. 20 by Paul F. Knouse, Jr. and Johnnie P. Pearson The 125th Annual Meeting of the Wachovia Historical Society was held virtually last Oc- tober 20, 2020, a change in our original plans for the meeting due to the pandemic. WHS is most grateful to Mr. Erik Salzwedel, Business Manager of the Moravian Music Foundation. Erik did a masterful job of working with Annual Meeting chair, Johnnie P. Pearson, to string together music recordings, presentations by WHS Board Members, the Annual Oration, and the presentation of the Archie K. Davis Award in a seamless video production of our annual meeting Inside Spring 2021 on WHS’s own You Tube channel. We are also pleased that those una- ble to view the meeting “live” may still view the video at any time on this channel. Thank you, Erik and Johnnie, and all participants, for your work and for making it possible to continue our Annual Meet- 125th Annual Meeting…...pp. 1-5 ing tradition. Renew Your Membership.…...p.5 The October 20th telecast began with organ music by Mary Louise 2020 Archie K. Davis Award Kapp Peeples from the CD, “Sing Hallelujah,” and instrumental mu- Winner…………….…….....p. 6 sic from the Moravian Lower Brass in the CD, “Harmonious to President’s Report…….……..p. 7 Dwell.” Both CD’s are produced by and available for sale from the 126th Annual Meeting…..…..p. 8 Moravian Music Foundation (see covers Join the Guild!.................…..p. -

Old Salem Historic District Design Review Guidelines

Old Salem Historic District Guide to the Certificate of Appropriateness (COA) Process and Design Review Guidelines PREFACE e are not going to discuss here the rules of the art of building “Was a whole but only those rules which relate to the order and way of building in our community. It often happens due to ill-considered planning that neighbors are molested and sometimes even the whole community suffers. For such reasons in well-ordered communities rules have been set up. Therefore our brotherly equality and the faithfulness which we have expressed for each other necessitates that we agree to some rules and regulation which shall be basic for all construction in our community so that no one suffers damage or loss because of careless construction by his neighbor and it is a special duty of the Town council to enforce such rules and regulations. -From Salem Building” Regulations Adopted June 1788 i n 1948, the Old Salem Historic District was subcommittee was formed I established as the first locally-zoned historic to review and update the Guidelines. district in the State of North Carolina. Creation The subcommittee’s membership of the Old Salem Historic District was achieved included present and former members in order to protect one of the most unique and of the Commission, residential property significant historical, architectural, archaeological, owners, representatives of the nonprofit and cultural resources in the United States. and institutional property owners Since that time, a monumental effort has been within the District, and preservation undertaken by public and private entities, and building professionals with an nonprofit organizations, religious and educational understanding of historic resources. -

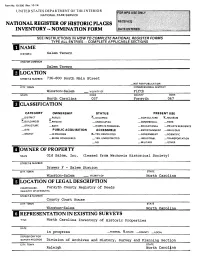

Hclassification

Form No. 10-300 (Rev. 10-74) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOWTO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS [NAME HISTORIC Salem Tavern AND/OR COMMON Salem Tavern LOCATION STREET& NUMBER 736-800 South Main Street _NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Winston-Salem __. VICINITY OF Fifth STATE CODE COUNTY CODE North Carolina 037 Forsyth 067 HCLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE _DISTRICT —PUBLIC •^-OCCUPIED _ AGRICULTURE X_MUSEUM ^LBUILDINGIS) —PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE _BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _JN PROCESS X_YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC _ BEING CONSIDERED — YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION _ NO —MILITARY —OTHER: OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Old Salem, Inc. (leased from Wachovia Historical Society) STREET & NUMBER Drawer F - Salem Station CITY. TOWN STATE Winston-Salem _ VICINITY OF North Carolina LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, Forsyth County Registry of Deeds REGISTRY OF DEEDS,ETC. STREET & NUMBER County Court House CITY. TOWN STATE Winston-Salem North Carolina | REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE North Carolina Inventory of Historic Properties DATE in progress —FEDERAL X.STATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS Division of Archives and History, Survey and Planning Section CITY. TOWN STATE Raleigh North Carolina DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —UNALTERED ^.ORIGINAL SITE .^EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED _GOOD —RUINS FALTERED restored MOVED DATE- _FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The Salem Tavern is located on the west side of South Main Street (number 736-800) in the restored area of Old Salem, now part of Winston-Salem, North Carolina. -

Applying the Educational Principles of Comenius

Applying The Educational Principles Of Comenius BY DENNIS L. PETERSON n their never-ending search for better ways to teach, educa- as “the terror of boys and the slaughterhouses of the mind” tors are tempted to be enamored of anything new and to (Curtis, et al., n.d.). Ieschew what they perceive to be outdated or old-fashioned. The friendly headmaster, however, “recognized his gifts Sometimes, however, some of the best “new” teaching prin- and encouraged him to train for the ministry” (Pioneers of ciples turn out to be long-forgotten or neglected old ways. Psychology, 2001). Comenius went on to study at Herborn and Such might be the case with the educational principles of Heidelberg, during which time he adopted the Latinized name seventeenth-century churchman and educator Comenius. His Comenius. ideas at first were considered radical or revolutionary, but they Returning home in 1614, he became headmaster of the quickly proved to be “the wave of the future.” He has been high school; a minister could not be ordained until he was acclaimed as “the greatest pedagogue of the Reformation era” twenty-four, and Comenius was too young. Two years later (Grimm, 1973) and is widely considered to be “the Father of he was ordained in the church of the Unitas Fratrum, vari- Modern Education” (Curtis, 1987). ously known as the Moravians, the Unity, the United Brethren, Unfortunately, many teachers today are unfamiliar with ei- and the Unity of the Brethren. In 1618, he became the pastor ther the man or his contributions to their profession. Recently, at Fulnek and settled down to a life of academic studies and however, a resurgence of interest in his work has been occur- spiritual service to his congregation. -

Jan Amos Comenius a Brief Bio on the "Father" of Modern Education

Jan Amos Comenius A brief bio on the "Father" of modern education. Some brief Notes on Jan Amos Comenius By Dr. C. Matthew McMahon Have you ever heard of Jan Amos Comenius? Do not be too overwhelmed with grief if you have not. In our day, most of the world has not heard of him. Regardless of your denominational distinction, Comenius is someone Christians should become familiar with. He wrote over 154 books in his lifetime, even after all of his original manuscripts were burned during a rebellion in Holland. He was an amazing and prolific educator, and has been stamped The Father of Modern Education. Born March 28, 15 92, orphaned early, educated at the universities of Herborn and Heidelberg, Comenius began working as a pastor and parochial school principal in 1618, the year the Thirty Years war began. After the defeat of the Protestant armies in the Battle of White Mountain one of the most disastrous events in Czech historyhe barely escaped with his life while enemy soldiers burned down his house. Later, his young wife and two small children died of the plague. For seven years he lived the life of a fugitive in his own land, hiding in deserted huts, in caves, even in hollow trees. Early in 1628 he joined one of the small groups of Protestants who fled their native Moravia to await better times in neighboring Poland. He never saw his homeland again. For 42 years of his long and sorrowful life he roamed the countries of Europe as a homeless refugee. He was always poor. -

Coversheet for Thesis in Sussex Research Online

A University of Sussex PhD thesis Available online via Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/ This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Please visit Sussex Research Online for more information and further details ‘Providence and Political Economy’: Josiah Tucker’s Providential Argument for Free Trade Peter Xavier Price PhD Thesis in Intellectual History University of Sussex April 2016 2 University of Sussex Peter Xavier Price Submitted for the award of a PhD in Intellectual History ‘Providence and Political Economy’: Josiah Tucker’s Providential Argument for Free Trade Thesis Summary Josiah Tucker, who was the Anglican Dean of Gloucester from 1758 until his death in 1799, is best known as a political pamphleteer, controversialist and political economist. Regularly called upon by Britain’s leading statesmen, and most significantly the Younger Pitt, to advise them on the best course of British economic development, in a large variety of writings he speculated on the consequences of North American independence for the global economy and for international relations; upon the complicated relations between small and large states; and on the related issue of whether low wage costs in poor countries might always erode the competitive advantage of richer nations, thereby establishing perpetual cycles of rise and decline. -

The Moravian Church and the White River Indian Mission

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1991 "An Instrument for Awakening": The Moravian Church and the White River Indian Mission Scott Edward Atwood College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the History of Religion Commons, Indigenous Studies Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Atwood, Scott Edward, ""An Instrument for Awakening": The Moravian Church and the White River Indian Mission" (1991). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539625693. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-5mtt-7p05 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. "AN INSTRUMENT FOR AWAKENING": THE MORAVIAN CHURCH AND THE WHITE RIVER INDIAN MISSION A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements-for the Degree of Master of Arts by Scott Edward Atwood 1991 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Author Approved, May 1991 <^4*«9_^x .UU James Axtell Michael McGiffert Thaddeus W. Tate, Jr. i i TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS................................................................................. -

Icaltion Wnelr 01

Form 10·00r0 OMS No. 1024-0018 10-31-84 entered See instructions in How to (.;omr.)felre HelQISrer Forms all en1tnE!!s--C()mlolete sections historic Hylehurst street & number 224 S. Cherry Street __ not for publication city, town Winston-Salem __ vicinity of s~~ North Carolina code 037 Forsyth code 067 icaltion Category Ownership Status Present Use __ district public ~ occupied __ agriculture __ museum -.X. building(s) ---X- private __ unoccupied __ commercial park __ structure __ both __ work in progress __ educational --x- private residence __ site Public Acquisition Accessible __ entertainment __ religious __ object __ in process ~ yes: restricted __ government __ scientific \.TTA being considered __ yes: unrestricted __ industrial __ transportation N,A __ no other: wnelr 01 name Mrs. R. A. McCuiston street & number 224 S. Cherry Street Winston-Salem ---- __ vicinity of state courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. Forsyth County Hall of Justice, Registry of Deeds street & number Main Street Winston-Salem state North Carolina From Frontier to Factory, An Architectural title History of Forsyth County has this property been determined eligible? __ yes ~ no date 1982 __ federal __ state ~ county __ local depository for survey records N.C. Division of Archives and History city, town Raleigh state North Carol; na ru' I IFU In !:!I I site __ ruins __ moved date _____________ __ fair appearance Hylehurst, built for John W.. Fries in 1884, is a Queen Anne-style dwelling designed by Henry Hudson Holly. The three-story frame structure stands facing south on a lot which originally included the entire block bounded by Cherry, Brookstown, Marshall and High streets in Salem. -

Z T:--1 ( Signa Ure of Certifying Ohicial " F/ Date

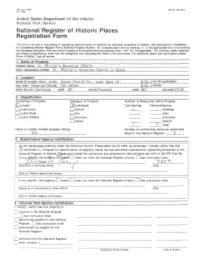

NPS Form 10-900 008 No. 1024-0018 (Rev. 8-86) U National Park Service This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations of eligibility for individual properties or districts. See instructions in Guidelines for Completing National Register Forms (National Register Bulletin 16). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the requested information. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, styles, materials, and areas of significance, enter only the categories and subcategories listed in the instructions. For additional space use continuation sheets (Form 1 0-900a). Type all entries. 1. Name of Property historic name St. Philip's Moravian Church other names/site number St. Philip' s ~1oravian Church in Salem city, town Hinston-Salem, Old Salem vicinity state North Carolina code NC county Forsyth code zip code 27108 Ownership of Property Category of Property Number of Resources within Property KJ private [Zl building(s) Contributing Noncontributing o public-local Ddistrict 1 ___ buildings o public-State DSi1e ___ sites o public-Federal D structure ___ structures Dobject _---,...,--------objects 1 __O_Total Name of related multiple property listing: Number of contributing resources previously N/A listed in the National Register 0 As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this ~ nomination 0 request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National R~g~ter of Historic~nd me~Js the procedural a~d profes~ional r.eq~irements set f~rth .in 36 CFR Part 60. -

Moravian Moravian

Dates to remember Prayer Notes moravianmoravian 16 February 2nd [4th After Epiphany] Matthew 5:1-12 Feb Education Sunday Divine Teacher, who alone possesses the words of eternal life and who taught www.educationsunday.org the crowds from the mountain, grant us to sit at your feet that we may listen FEBRUARY 2014 FEBRUARY messengermessenger to all the gracious words which come from your mouth. Reveal to us the hidden wisdom of your gospel, that we may hunger and thirst for the 24 righteousness which only you can give: satisfy us that we might be sons and 9 daughters of God and be found among those whose seek first the blessedness Feb Mar of the kingdom of heaven. If we are called to walk the path of ridicule and persecution for your name's sake grant us joy as we remember the holy Fair Trade Fortnight company we follow and the joyful welcome which awaits all your faithful Brother David Newman Rediscovering www.fairtrade.org.uk disciples. Amen reflects on the ministry February 9th [5th after Epiphany] Matthew 5:13-20 Founding of of teaching a Vocation Eternal Truth, make us attentive to your word that we may learn to know 1 the Brethren's you; and knowing you to love you; and loving you, to become like you. Let In the UK Church Calendar, Education I qualified as a teacher of secondary Cheltenham at the home of the one of Mar Church in 1457 the truth which you reveal enlighten our minds that in your light we may Sunday traditionally falls in the month mathematics through three years of the six of us who had remained in the see light and walk without stumbling as in the day, and by your Spirit rightly of February; a Sunday when we think of study at St Paul's College, Cheltenham. -

A Church Apart: Southern Moravianism and Denominational Identity, 1865-1903

A CHURCH APART: SOUTHERN MORAVIANISM AND DENOMINATIONAL IDENTITY, 1865-1903 Benjamin Antes Peterson A Thesis Submitted to the University of North Carolina Wilmington in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Department of History University of North Carolina Wilmington 2008 Approved by Advisory Committee Glen A. Harris Walter H. Conser William D. Moore Chair Accepted by Dean, Graduate School TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT ....................................................................................................................... iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ............................................................................................... iv DEDICATION .....................................................................................................................v LIST OF FIGURES ........................................................................................................... vi INTODUCTION ..................................................................................................................1 CHAPTER ONE – “TO CARE FOR OURSELVES”: A MORAVIAN SCHISM ...........13 CHAPTER TWO – “REVIVALISM AND KINDRED SUBJECTS”: A CHALLENGE TO LITURGICAL WORSHIP ..............................................................................34 CHAPTER THREE – “BLESSED AND EXTENDED”: MORAVIAN DENOMINATIONAL SUNDAY SCHOOLS ......................................................53 CHAPTER FOUR – “PATRIOTIC COMMUNICANTS”: THE MATURE SOUTHERN CHURCH .........................................................................................74 -

The Trumpet and the Unitas Fratrum

4 HISTORIC BRASS SOCIETY JOURNAL THETRUMPET AND THE UNITAS FRATRUM Ernest H. Gross Ill he purpose of this article is to examine and document a phenomenon which has only recently been given any auention: the use of the natural, or baroque, Ttrumpet by the Unitas Fratrum, or Moravian church in Germany and its subsequentemployment on the North American continent during theeighteenth century. While there is evidence that trumpets were played in many locations throughout the American colonies,' the scope of this article is very specific; it deals only with how the Moravian church, a group of immigrants seeking religious freedom and the opportunity to minister to those in the New World, came to employ trumpets in their religious communities and worship practices. First, however, it will be necessary to define some of the Moravian religious practices and terminology before proceeding. These customs either involved music, or had a profound influence on the development of the church's musical traditions. Many of the rituals of the Moravian church were attempts to return to the Christianity of the New Testament. A group of young believers in Herrnhut, Saxony, in 1732decided to hold an Easter service consisting of hymns of praise at the church's burial site early on aster m~rning.~ This simple service was very effective, and soon was made a custom in the Moravian church. Instrumental accompaniment was added shortly afterward, and today the massed instrumentalists and singing congregation at a Moravian Easter service are impressive indeed. The place where these services were held was known simply as "God's Acre." This was the Moravians' term for the plot of land where the bodies of believers were buried, or "planted" to await the "first fruits" of the ~esumction.~It was the firm belief in the Resurrection and eternal life that shaped all of thecustoms having to do with God's Acre, the early Easter service, and the use of funeral chorales.