John Barrett Murphy Civil War Soldier Compiled and Edited by Al Palmer Lambertville, MI May 2009

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

89.1963.1 Iron Brigade Commander Wayne County Marker Text Review Report 2/16/2015

89.1963.1 Iron Brigade Commander Wayne County Marker Text Review Report 2/16/2015 Marker Text One-quarter mile south of this marker is the home of General Solomon A. Meredith, Iron Brigade Commander at Gettysburg. Born in North Carolina, Meredith was an Indiana political leader and post-war Surveyor-General of Montana Territory. Report The Bureau placed this marker under review because its file lacked both primary and secondary documentation. IHB researchers were able to locate primary sources to support the claims made by the marker. The following report expands upon the marker points and addresses various omissions, including specifics about Meredith’s political service before and after the war. Solomon Meredith was born in Guilford County, North Carolina on May 29, 1810.1 By 1830, his family had relocated to Center Township, Wayne County, Indiana.2 Meredith soon turned to farming and raising stock; in the 1850s, he purchased property near Cambridge City, which became known as Oakland Farm, where he grew crops and raised award-winning cattle.3 Meredith also embarked on a varied political career. He served as a member of the Wayne County Whig convention in 1839.4 During this period, Meredith became concerned with state internal improvements: in the early 1840s, he supported the development of the Whitewater Canal, which terminated in Cambridge City.5 Voters next chose Meredith as their representative to the Indiana House of Representatives in 1846 and they reelected him to that position in 1847 and 1848.6 From 1849-1853, Meredith served -

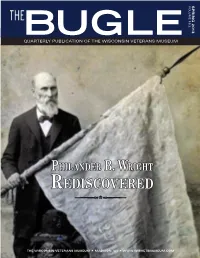

Rediscovered

VOLUME 19:2 2013 SPRING QUARTERLY PUBLICATION OF THE WISCONSIN VETERANS MUSEUM PHILANDER B. WRIGHT REDISCOVERED THE WISCONSIN VETERANS MUSEUM MADISON, WI WWW.WISVETSMUSEUM.COM FROM THE SECRETARY sure there was strong support Exhibit space was quickly for the museum all around the filled, as relics from those state, from veterans and non- subsequent wars vastly veterans alike. enlarged our collections and How the Wisconsin Veterans the museum became more Museum came to be on the and more popular. By the Capitol Square in its current 1980s, it was clear that our incarnation is best answered museum needed more space by the late Dr. Richard Zeitlin. for exhibits and visitors. Thus, As the former curator of the with the support of many G.A.R. Memorial Hall Museum Veterans Affairs secretaries, in the State Capitol and the Governor Thompson and Wisconsin War Museum at the many legislators, we were Wisconsin Veterans Home, he able to acquire the space and was a firsthand witness to the develop the exhibits that now history of our museum. make the Wisconsin Veterans Zeitlin pointed to a 1901 Museum a premiere historical law that mandated that state attraction in the State of officials establish a memorial Wisconsin. WDVA SECRETARY JOHN SCOCOS dedicated to commemorating The Wisconsin Department Wisconsin’s role in the Civil of Veterans Affairs is proud FROM THE SECRETARY War and any subsequent of our museum and as we Greetings! The Wisconsin war as a starting point for commemorate our 20th Veterans Museum as you the museum. After the State anniversary in its current know it today opened on Capitol was rebuilt following location, we are also working June 6, 1993. -

“Never Have I Seen Such a Charge”

The Army of Northern Virginia in the Gettysburg Campaign “Never Have I Seen Such a Charge” Pender’s Light Division at Gettysburg, July 1 D. Scott Hartwig It was July 1 at Gettysburg and the battle west of town had been raging furiously since 1:30 p.m. By dint of only the hardest fighting troops of Major General Henry Heth’s and Major General Robert E. Rodes’s divisions had driven elements of the Union 1st Corps from their positions along McPherson’s Ridge, back to Seminary Ridge. Here, the bloodied Union regiments and batteries hastily organized a defense to meet the storm they all knew would soon break upon them. This was the last possible line of defense beyond the town and the high ground south of it. It had to be held as long as possible. To break this last line of Union resistance, Confederate Third Corps commander, Lieutenant General Ambrose P. Hill, committed his last reserve, the division of Major General Dorsey Pender. They were the famed Light Division of the Army of Northern Virginia, boasting a battle record from the Seven Days battles to Chancellorsville unsurpassed by any other division in the army. Arguably, it may have been the best division in Lee’s army. Certainly no organization of the army could claim more combat experience. Now, Hill would call upon his old division once more to make a desperate assault to secure victory. In many ways their charge upon Seminary Ridge would be symbolic of why the Army of Northern Virginia had enjoyed an unbroken string of victories through 1862 and 1863, and why they would meet defeat at Gettysburg. -

Course Reader

Course Reader Gettysburg: History and Memory Professor Allen Guelzo The content of this reader is only for educational use in conjunction with the Gilder Lehrman Institute’s Teacher Seminar Program. Any unauthorized use, such as distributing, copying, modifying, displaying, transmitting, or reprinting, is strictly prohibited. GETTYSBURG in HISTORY and MEMORY DOCUMENTS and PAPERS A.R. Boteler, “Stonewall Jackson In Campaign Of 1862,” Southern Historical Society Papers 40 (September 1915) The Situation James Longstreet, “Lee in Pennsylvania,” in Annals of the War (Philadelphia, 1879) 1863 “Letter from Major-General Henry Heth,” SHSP 4 (September 1877) Lee to Jefferson Davis (June 10, 1863), in O.R., series one, 27 (pt 3) Richard Taylor, Destruction and Reconstruction: Personal Experiences of the Late War (Edinburgh, 1879) John S. Robson, How a One-Legged Rebel Lives: Reminiscences of the Civil War (Durham, NC, 1898) George H. Washburn, A Complete Military History and Record of the 108th Regiment N.Y. Vols., from 1862 to 1894 (Rochester, 1894) Thomas Hyde, Following the Greek Cross, or Memories of the Sixth Army Corps (Boston, 1894) Spencer Glasgow Welch to Cordelia Strother Welch (August 18, 1862), in A Confederate Surgeon’s Letters to His Wife (New York, 1911) The Armies The Road to Richmond: Civil War Memoirs of Major Abner R. Small of the Sixteenth Maine Volunteers, ed. H.A. Small (Berkeley, 1939) Mrs. Arabella M. Willson, Disaster, Struggle, Triumph: The Adventures of 1000 “Boys in Blue,” from August, 1862, until June, 1865 (Albany, 1870) John H. Rhodes, The History of Battery B, First Regiment Rhode Island Light Artillery, in the War to Preserve the Union (Providence, 1894) A Gallant Captain of the Civil War: Being the Record of the Extraordinary Adventures of Frederick Otto Baron von Fritsch, ed. -

Battlefield Footsteps Programs Teacher and Student Guide

BATTL FI LD FOOTST PS Gettysburg National Military Park Preparation Materials for the Courage, Determination, and eadership student programs. U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Battlefield Footsteps Programs Teacher and Student Guide The following lessons have been prepared for you to present over the course of one or two class periods and/or to send home as study guides for your students. They will prepare them for the trip as well as build their anticipation for the program. Please be sure to have the students wear a nametag with their FIRST NAMES ONLY in large letters so that we can get to know them quickly on Field Trip Day. Causes of the American Civil War a lesson for all programs page 3 What was the Civil War really fought over? Let the people who lived through this emotional and complex time period tell you what it was like, and why they became involved in a war that would ultimately claim 620,000 lives. th “Courage and the 9 Massachusetts Battery” July 2, 1863 page 6 “Retreat by prolonge, firing!” is the order as your unit is sacrificed to buy time for the infantry to plug the gaps along Cemetery Ridge. Follow in the path and harried activity of this courageous artillery unit. “Determination and the 15th Alabama Infantry” July 2, 1863 page 10 Climb Big Round Top and attack Little Round Top after a forced march, and without any water! This program illustrates the strength, stamina and determination of these Confederate infantrymen. “Leadership and the 6th Wisconsin Infantry” July 1, 1863 page 14 “Align on the Colors” with Lt. -

General Orders the Newsletter of the Civil War Round Table of Milwaukee, Inc

GENERAL ORDERS The Newsletter of the Civil War Round Table of Milwaukee, Inc. Our 62nd Year and The Iron Brigade Association GENERAL ORDERS NO. 11-10 NOVEMBER 11, 2010 November 2011 ROBERT GIRARDI IN THIS ISSUE Civil War Corps Command: A Study in Leadership CWRT News ....................................................2 The American Civil War was the great battleground upon which the Regular Army of the Announcements ...........................................2 United States came of age. For the first time, massive deployment of large armies and This Month in Civil War History ...............2 the logistical and intelligence networks necessary to support them were put into effect. Looking Back ..................................................3 The nature of combat and command in the Civil War necessitated the reorganization of Kenosha Civil War Museum ......................3 the armies. Brigades and Divisions, previously the largest organizational bodies, were Robert Wynstra Interview..........................4 replaced by the introduction of army corps for the first time. The solution to the problem Film Clips ........................................................6 was a problem in itself. No officers of the United States Army had ever commanded any- Civil War News ...............................................7 thing of the size and complexity of an army corps. While it is true that the army gained much practical experience in the Mexican War, that conflict was as nothing in its scope November Meeting Reservation .............7 and scale and in the responsibilities it taught to senior commanders, compared to the latter conflict. The largest army in the Mexican War would have been but a weak army OCTOBER MEETING AT A GLANCE corps in the Civil War that followed. November 11, 2010 A number of generals rose to command army corps in the Civil War. -

Cover of 1992 Edition) This Scene from the Gettysburg Cyclorama Painting

cover of 1992 edition) (cover of 1962 edition) This scene from the Gettysburg Cyclorama painting by Paul Philippoteaux potrays the High Water Mark of the Confederate cause as Southern Troops briefly pentrate the Union lines at the Angle on Cemetery Ridge, July 3, 1863. Photo by Walter B. Lane. GETTYSBURG National Military Park Pennsylvania by Frederick Tilberg National Park Service Historical Handbook Series No. 9 Washington, D.C. 1954 (Revised 1962, Reprint 1992) Contents a. THE SITUATION, SPRING 1863 b. THE PLAN OF CAMPAIGN c. THE FIRST DAY The Two Armies Converge on Gettysburg The Battle of Oak Ridge d. THE SECOND DAY Preliminary Movements and Plans Longstreet Attacks on the Right Warren Saves Little Round Top Culp's Hill e. THE THIRD DAY Cannonade at Dawn: Culp's Hill and Spangler's Spring Lee Plans a Final Thrust Lee and Meade Set the Stage Artillery Duel at One O'clock Climax at Gettysburg Cavalry Action f. END OF INVASION g. LINCOLN AND GETTYSBURG Establishment of a Burial Ground Dedication of the Cemetery Genesis of the Gettysburg Address The Five Autograph Copies of the Gettysburg Address Soldiers' National Monument The Lincoln Address Memorial h. ANNIVERSARY REUNIONS OF CIVIL WAR VETERANS i. THE PARK j. ADMINISTRATION k. SUGGESTED READINGS l. APPENDIX: WEAPONS AND TACTICS AT GETTYSBURG m. GALLERY: F. D. BRISCOE BATTLE PAINTINGS For additional information, visit the Web site for Gettysburg National Military Park Historical Handbook Number Nine 1954 (Revised 1962) This publication is one of a series of handbooks describing the historical and archeological areas in the National Park System administered by the National Park Service of the United States Department of the Interior. -

“I Have Never Seen the Like Before”

“I Have Never Seen the Like Before” Herbst Woods, July 1, 1863 D. Scott Hartwig Of the 160 acres that John Herbst farmed during the summer of 1863, 18 were in a woodlot on the northwestern boundary, adjacent to the farm owned by Edward McPherson. Until July 1, 1863 these woods provided shade for Herbst’s eleven head of cattle, wood for various needs around the farm, and some income. Because of the level of human and animal activity in these woods they were free of undergrowth, except for where they came up against Willoughby Run, a sluggish stream that meandered along their western border. Along this stream willows and brush grew thickly.1 Although Confederate troops passed down the Mummasburg road on June 26 on their way to Gettysburg, either Herbst’s farm was too far off the path of their march, or he was clever about hiding his livestock, for he suffered no losses. His luck at avoiding damage or loss from the Confederate invasion of Pennsylvania began to run out on June 30. It was known that a large force of Confederates had occupied Cashtown on June 29, causing a stir of uneasiness. William Comfort and David Finnefrock, the tenant farmers on the Emmanuel Harmon farm, Herbst’s neighbor west of Willoughby Run, chose to take their horses away to protect them. Herbst and John Slentz, the tenant who farmed the McPherson farm, apparently decided to try their chances and remained on their farms, thinking they stood a better chance of protecting their property if they remained.2 On the morning of June 30 a large Confederate infantry brigade under the command of General James J. -

The Iron Brigade in Civil War and Memory: the Black Hats from Bull Run to Appomattox and Thereafter

Civil War Book Review Spring 2013 Article 13 The Iron Brigade in Civil War and Memory: The Black Hats From Bull Run to Appomattox and Thereafter Fred Johnson Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/cwbr Recommended Citation Johnson, Fred (2013) "The Iron Brigade in Civil War and Memory: The Black Hats From Bull Run to Appomattox and Thereafter," Civil War Book Review: Vol. 15 : Iss. 2 . DOI: 10.31390/cwbr.15.2.15 Available at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/cwbr/vol15/iss2/13 Johnson: The Iron Brigade in Civil War and Memory: The Black Hats From Bul Review Johnson, Fred Spring 2013 Herdegen, Lance The Iron Brigade in Civil War and Memory: The Black Hats from Bull Run to Appomattox and Thereafter. Savas Beatie, $19.95 ISBN 978-1-61121-106-1 The Impact of the Black Hats on How We Remember Few stand as qualified to write a comprehensive history of the Union Army’s storied Iron Brigade as Lance Herdegen, the former director of the Institute for Civil War Studies at Carroll University. His latest work, The Iron Brigade in Civil War and Memory: the Black Hats from Bull Run to Appomattox and Thereafter, adds another title to his similarly focused works like The Men Stood Like Iron: How the Iron Brigade Won Its Name and Those Damned Black Hats: The Iron Brigade in the Gettysburg Campaign, winner of the Army Historical Foundation Distinguished Writing Award. Herdegen’s intimate familiarity with the topic and the archival sources pertaining to it are on full display in his current work. -

The Spectacle

National Park Service Arlington House U.S. Department of the Interior The Robert E. Lee Memorial The Spectacle Fall Open House - A Special Message for those Volunteering Thank you so much for your desire and dedication in making this year’s open house a success. As you may know, we are doing some different things this year. It will be very exciting but, perhaps, just a little confusing. Included in this message are instructions that will hopefully make it all make sense. Please plan to arrive by 6:00pm. You may come earlier if you wish to eat your dinner here in the OAB but don’t come later. Because of the lecture starting at 7:00pm we need to be dressed and ready a little earlier than in past years. There has been some difficulty getting the necessary car passes from the cemetery. So, we are providing the guards at the main gate with a list of all the volunteers who will be coming on October 10. If you Arlington House at night do not have a valid pass you will need to give your name to the guard as you enter. be at your scheduled station before the Please review the historical information visitors arrive there. For that reason, about your assigned location and prepare The lecture, by Dr. Thomas Battle, is an you should leave the lecture no later than accordingly. exciting addition to this year’s event. 7:20 (or 7:25 if you can walk quickly!). Because of this we want to give all our See you Friday! volunteers an opportunity to hear as We will rotate positions this year. -

April 2011 (773) 774-6781

4 The Civil War Round Table Grapeshot Schimmelfennig Boutique Sixty plus years of audio recordings of CWRT lectures by distinguished histori- Bulletin ans are available and can be purchased Board THE CIVIL WAR ROUND TABLE in either audio cassette or CD format. Founded December 3, 1940 For lecture lists, contact Hal Ardell at [email protected] or phone him at Volume LXXI, Number 8 Chicago, Illinois April 2011 (773) 774-6781. Future Meetings Regular meetings are held at the Each meeting features a book raffle, with Richard McMurray The Chicago History Museum is Holiday Inn Mart Plaza, 350 North sponsoring several events to coin- proceeds going to battlefield preserva- on tion. There is also a silent auction for Orleans Street, the second Friday of cide with the Sesquecentennial, each month, unless otherwise indicated. “A Georgian Looks at including the showing of the film books donated by Ralph Newman and others, again with proceeds benefiting April 8: Richard McMurry, “A Sherman” “Love & Valor” April 3rd. Phone battlefield preservation. 312 642-4600 or visit www.chica- Georgian Looks at Sherman” by Bruce Allardice gohistory.org for more on these May 13: Tom Schott, “Alexander “War is Hell.” “War is cruelty, and events. Upcoming Civil War Events 700th REGULAR Stephens and Jefferson Davis: A you cannot refine it.” “I can make April 1st, Northern Illinois CWRT: Marriage Made in Hell” MEETING this march, and I will make Geor- Richard McMurray Beginning in April the Union Marta Vincent on “Children’s Cloth- June 10: Peter Carmichael, Richard McMurray gia howl!” These and other colorful League Club will host monthly ing During the Civil War” whether this image of Sherman is presentations on the Civil War, “Robert E. -

Union Bands of the Civil War (1862-1865): Instrumentation and Score Analysis

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1973 Union Bands of the Civil War (1862-1865): Instrumentation and Score Analysis. (Volumes I and II). William Alfred Bufkin Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Bufkin, William Alfred, "Union Bands of the Civil War (1862-1865): Instrumentation and Score Analysis. (Volumes I and II)." (1973). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 2523. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/2523 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and dius cause a blurred image.