Ulithi Ulithi Had Cleaned out and Relieved Sister Ship No

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Micronesica 37(1) Final

Micronesica 37(1):163-166, 2004 A Record of Perochirus cf. scutellatus (Squamata: Gekkonidae) from Ulithi Atoll, Caroline Islands GARY J. WILES1 Division of Aquatic and Wildlife Resources, 192 Dairy Road, Mangilao, Guam 96913, USA Abstract—This paper documents the occurrence of the gecko Perochirus cf. scutellatus at Ulithi Atoll in the Caroline Islands, where it is possibly restricted to a single islet. This represents just the third known location for the species and extends its range by 975 km. Information gathered to date suggests the species was once more widespread and is perhaps sensitive to human-induced habitat change. The genus Perochirus is comprised of three extant species of gecko native to Micronesia and Vanuatu and an extinct form from Tonga (Brown 1976, Pregill 1993, Crombie & Pregill 1999). The giant Micronesian gecko (P. scutellatus) is the largest member of the genus and was until recently considered endemic to Kapingamarangi Atoll in southern Micronesia, where it is common on many islets (Buden 1998a, 1998b). Crombie & Pregill (1999) reported two specimens resem- bling this species from Fana in the Southwest Islands of Palau; these are consid- ered to be P. cf. scutellatus pending further comparison with material from Kapingamarangi (R. Crombie, pers. comm.). Herein, I document the occurrence of P. cf. scutellatus from an additional site in Micronesia. During a week-long fruit bat survey at Ulithi Atoll in Yap State, Caroline Islands in March 1986 (Wiles et al. 1991), 14 of the atoll’s larger islets com- prising 77% of the total land area were visited. Fieldwork was conducted pri- marily from dawn to dusk, with four observers spending much of their time walking transects through the forested interior of each islet. -

Congressional Record—Senate S5954

S5954 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD Ð SENATE May 25, 1999 By Mr. NICKLES: SUBMISSION OF CONCURRENT AND communities. And just last week, the S. 1116. A bill to amend the Internal Rev- SENATE RESOLUTIONS Senate approved a juvenile justice bill enue Code of 1986 to exclude income from the containing Charitable Choice for serv- transportation of oil and gas by pipeline The following concurrent resolutions from subpart F income; to the Committee on and Senate resolutions were read, and ices provided to at-risk juveniles, such Finance. referred (or acted upon), as indicated: as counseling for troubled youth. By Mr. LOTT (for himself, Mr. COCH- The Charitable Choice provision in By Mr. SPECTER: RAN, Mr. ROBB, and Mr. JEFFORDS): the 1996 welfare reform law was one S. Con. Res. 34. A concurrent resolution re- S. 1117. A bill to establish the Corinth Unit way to achieve the goal of inviting the of Shiloh National Military Park, in the vi- lating to the observance of ``In Memory'' Day; to the Committee on the Judiciary. greater participation of charitable and cinity of the city of Corinth, Mississippi, and faith-based organizations in providing in the State of Tennessee, and for other pur- f poses; to the Committee on Energy and Nat- services to the poor. The provision al- ural Resources. STATEMENTS ON INTRODUCED lows charitable and faith-based organi- By Mr. SCHUMER (for himself, Mrs. BILLS AND JOINT RESOLUTIONS zations to compete for contracts and FEINSTEIN, Mr. CHAFEE, Mr. GREGG, By Mr. ASHCROFT: voucher programs on an equal basis Mr. SANTORUM, and Mr. MOYNIHAN): S. -

January Cover.Indd

Accessories 1:35 Scale SALE V3000S Masks For ICM kit. EUXT198 $16.95 $11.99 SALE L3H163 Masks For ICM kit. EUXT200 $16.95 $11.99 SALE Kfz.2 Radio Car Masks For ICM kit. KV-1 and KV-2 - Vol. 5 - Tool Boxes Early German E-50 Flakpanzer Rheinmetall Geraet sWS with 20mm Flakvierling Detail Set EUXT201 $9.95 $7.99 AB35194 $17.99 $16.19 58 5.5cm Gun Barrels For Trumpter EU36195 $32.95 $29.66 AB35L100 $21.99 $19.79 SALE Merkava Mk.3D Masks For Meng kit. KV-1 and KV-2 - Vol. 4 - Tool Boxes Late Defender 110 Hardtop Detail Set HobbyBoss EUXT202 $14.95 $10.99 AB35195 $17.99 $16.19 Soviet 76.2mm M1936 (F22) Divisional Gun EU36200 $32.95 $29.66 SALE L 4500 Büssing NAG Window Mask KV-1 Vol. 6 - Lubricant Tanks Trumpeter KV-1 Barrel For Bronco kit. GMC Bofors 40mm Detail Set For HobbyBoss For ICM kit. AB35196 $14.99 $14.99 AB35L104 $9.99 EU36208 $29.95 $26.96 EUXT206 $10.95 $7.99 German Heavy Tank PzKpfw(r) KV-2 Vol-1 German Stu.Pz.IV Brumbar 15cm STuH 43 Gun Boxer MRAV Detail Set For HobbyBoss kit. Jagdpanzer 38(t) Hetzer Wheel mask For Basic Set For Trumpeter kit - TR00367. Barrel For Dragon kit. EU36215 $32.95 $29.66 AB35L110 $9.99 Academy kit. AB35212 $25.99 $23.39 Churchill Mk.VI Detail Set For AFV Club kit. EUXT208 $12.95 SALE German Super Heavy Tank E-100 Vol.1 Soviet 152.4mm ML-20S for SU-152 SP Gun EU36233 $26.95 $24.26 Simca 5 Staff Car Mask For Tamiya kit. -

Three Views of the Attack on Pearl Harbor: Navy, Civilian, and Resident Perspectives

MARJORIE KELLY Three Views of the Attack on Pearl Harbor: Navy, Civilian, and Resident Perspectives POPULAR UNDERSTANDING of the attack on Pearl Harbor will undoubtedly be colored by the release of the $135 million epic Pearl Harbor, the fifth most expensive film in movie history. Described as "an adventure/romance in which everything blows up at the end," Disney's Touchstone Pictures recreated the December 7, 1941 Japa- nese attack on the U.S. Navy as its visual climax with an impressive array of special effects. During the film's production, Honolulu Star- Bulletin journalist Burl Burlingame was already at work enumerating the movie's technological inaccuracies and shortcomings.1 In a sec- ond article which focused on the film's portrayal of race, Burlingame noted that originally the producers, executives, and director of Pearl Harbor said they would spare no expense in accurately portraying the attack—even obtaining the approval of veterans groups. During the filming, however, producer Jerry Bruckheimer "waffled mightily on the subject of accuracy," recharacterizing his project as "gee-whiz-it's- just-entertainment."2 With the film's release on Memorial Day of 2001, a new generation's perception of the attack will likely forever be influenced by the images and impressions engendered by the film. Also influential, however, have been the two films used to orient the more than one million visitors a year to the USS Arizona Memo- rial, administered by the National Park Service (NPS) on the Pearl Marjorie Kelly is a cultural anthropologist whose research specialty is the representation of culture in museum and tourist settings. -

Report Japanese Submarine 1124

REPORT JAPANESE SUBMARINE 1124 Mike McCarthy Maritime Archaeology Department WAMaritime Museum Cliff Street, Fremantle, WA 6160 October 1990 With research, advice and technical assistance from Captain David Tomlinson Or David Ramm Or J. Fabris Or Thomas O. Paine Mr Garrick Gray Mr George G. Thompson Mr Henri Bourse Mr J. Bastian Mr P.J. Washington RACAL The Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade The Department of the Arts, Sport, the Environment, Tourism and Territories Underwater Systems Australia Report-Department of Maritime Archaeology, Western Australian Museum, No. 43 2 Background to the report In July 1988, a wreck believed to be the SS Koombanah, which disappeared with all hands in waters off Western Australia in 1921, was officially reported to the W. A. Museum and the federal government by Captain David Tomlinson, (Master/owner of the Darwin based Research Vessel Flamingo Bay) and Mr Mike Barron, a Tasmanian associate of Tomlinson's, fr;om the Commonwealth Fisheries. In order to facilitate an inspection of the site, it was decided on analysis of the available options and in the light of the W.A. Museum's policy of involving the finders where possible, to join with Messrs Tomlinson and Barron in an inspection out of Darwin on board the RV Flamingo Bay, a very well equipped and most suitable vessel for such a venture. Due to the depth of the water in which the site lay and the distance off shore, this required not only the charter of Flamingo Bay which normally runs at circa $2000 per day, but also the hire of a sophisticated position fixing system, a Remote Operated Submersible Vehicle with camera (ROV), echo sounder and side scan sonar. -

Special Presentation

Minutes of the Meeting of June 8, 2011 Pledge of Allegiance: Commander Willis E “Bill” Hardy, USN (Ret.) Navy Cross, Distinguished Flying Cross, Air Medals, PUC Invocation: Chairman Jack Hammett Taps: W. T. “Duke” Steinken, Captain, USMC (Ret.) Duke Steinken decorated with Distinguished Flying Cross Guests Present: (25) Alison Akau, Linda Anderson, Cathy Barnes, Jess Bequette, Larry Blake, Guy V. Coulombe, Cherrie Danks, Carmen Holiday, Andrew Hutchins, Michael Knybel, Tom Knybel, Lou Kridelbaugh, Ray LeCompte, Mike Linkiewicz, Daniel Martinez, Edison W. Miller, Tom Miller, Fred Pellicciotti, James Powers, Ray Roudine, Jim Thurn, Jack Walters, George Widly, Edward Wolfe, and Rob Wood, Members Present: (59) Sally Adams, Kelly Alacala, Jim Baker, Bette Bell, Howard Bender , Frank Callahan, George Ciampa, Robby Conn, Bus Cornelius, Robert Cowley, Roberta Cowley, Bob Dugan, Dave Ferguson, Kirk Ferguson, Dan Gillespie, Archie Gregory, Ray Grissom, Herb Guiness, , Frank Haigler, Jack Hammett, Arnold Hanson, Dale Hanson, Shirley Hanson, Bill Hardy, Ramona Hill, Carmen Holiday, William Holiday, Dan Huston, Tony Iantorno, David Lester, Frank Mannino, Ted Marinos, Vern Martin, Robert Meyer, Charles Mitchell, Dick O’Brien, Helen Possemato, Lou Possemato, Gladys Refakes, Tim Richards, Larry Schnitzer, Terry Schnitzer, Jeff Sebek, Harry Selling, Judy Selling, John Skara, Bob Sternfels, Ted Tanner, Brent Theobold, Dan Vigna, Phillip Vinci, Gene Wallace, Linda Wallace, Denise Weiland, Fred Whitaker, Scott Williams, Rayman Wong, Sid Yahn and Elizabeth Yee. We were honored by a special guest, National Park Service Ranger, Daniel Martinez, from the USS Arizona Memorial at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. His team was in Costa Mesa to gather first hand oral history from the men that served in the Pacific Theater during WWII. -

PDF Download Sunk: the Story of the Japanese Submarine Fleet

SUNK: THE STORY OF THE JAPANESE SUBMARINE FLEET, 1941-1945 PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Mochitsura Hashimoto, Edward L. Beach | 280 pages | 31 May 2010 | Progressive Press | 9781615775811 | English | Palm Desert, United States Sunk: The Story of the Japanese Submarine Fleet, 1941-1945 PDF Book The divers cross-referenced military records of three submarines sunk in the area during World War II with the possible locations of wrecks reported by fishermen who had snagged nets on submerged obstacles, said team member Lance Horowitz, an Australian based on Thailand's southern island of Phuket. A handful survived in , broken up in Almost sailors died while awaiting rescue. There is a small attempt to organize the stories into tactical and operational-level and strategic operations. They innovated with their mm tubes 21 in. This was the fifth submarine discovered by Taylor's Lost 52 Project, which aims to find the 52 U. The Iclass submarines 6 ordered, 1 completed displaced 4, tons, had a range of 13, nmi 24, km; 15, mi , torpedo tubes, mortar and 25 mm guns AA. In , Hashimoto volunteered for the submarine service, [2] and in , he served aboard destroyers and submarine chasers off the shores of the Republic of China. Dimensions 49 m long, 5 m wide, 2. Architectural Digest. The first class of 6 units was issued too late, and only three units, I, and , built at Kure, entered service briefly in July This happened on 30 July, days away from the capitulation. With the Nuremberg Trials underway and Japanese war crimes during the war coming to light, the announcement of Hashimoto's appearance in testimony against an American officer caused considerable controversy in the American news media. -

The USS Arizona Memorial

National Park Service Teaching with Historic Places U.S. Department of the Interior Remembering Pearl Harbor: The USS Arizona Memorial Remembering Pearl Harbor: The USS Arizona Memorial (National Park Service Photo by Jayme Pastoric) Today the battle-scarred, submerged remains of the battleship USS Arizona rest on the silt of Pearl Harbor, just as they settled on December 7, 1941. The ship was one of many casualties from the deadly attack by the Japanese on a quiet Sunday that President Franklin Roosevelt called "a date which will live in infamy." The Arizona's burning bridge and listing mast and superstructure were photographed in the aftermath of the Japanese attack, and news of her sinking was emblazoned on the front page of newspapers across the land. The photograph symbolized the destruction of the United States Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor and the start of a war that was to take many thousands of American lives. Indelibly impressed into the national memory, the image could be recalled by most Americans when they heard the battle cry, "Remember Pearl Harbor." More than a million people visit the USS Arizona Memorial each year. They file quietly through the building and toss flower wreaths and leis into the water. They watch the iridescent slick of oil that still leaks, a drop at a time, from ruptured bunkers after more than 50 years at the bottom of the sea, and they read the names of the dead carved in marble on the Memorial's walls. National Park Service Teaching with Historic Places U.S. Department of the Interior Remembering Pearl Harbor: The USS Arizona Memorial Document Contents National Curriculum Standards About This Lesson Getting Started: Inquiry Question Setting the Stage: Historical Context Locating the Site: Map 1. -

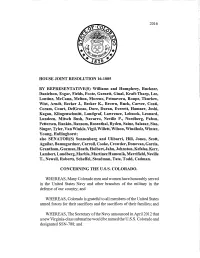

House Joint Resolution 16-1005 by Representative(S

2016 HOUSE JOINT RESOLUTION 16-1005 BY REPRESENTATIVE(S) Williams and Humphrey, Buckner, Danielson, Esgar, Fields, Foote, Garnett, Ginal, Kraft-Tharp, Lee, Lontine, McCann, Melton, Moreno, Primavera, Roupe, Thurlow, Wist, Arndt, Becker J., Becker K., Brown, Buck, Carver, Conti, Coram, Court, DelGrosso, Dore, Duran, Everett, Hamner, Joshi, Kagan, Klingenschmitt, Landgraf, Lawrence, Lebsock, Leonard, Lundeen, Mitsch Bush, Navarro, Neville P., Nordberg, Pabon, Pettersen, Rankin,Ransom, Rosenthal, Ryden, Saine, Salazar, Sias, Singer, Tyler, VanWinkle, Vigil, Willett, Wilson~ Windholz, Winter, Young, Hullinghorst; also SENATOR(S) Sonnenberg and Ulibarri, Hill, Jones, Scott, Aguilar, Baumgardner,Carroll, Cooke, Crowder,Donovan, Garcia, Grantham, Guzman, Heath, Holbert,Jahn,Johnston, Kefalas, Kerr, Lambert,Lundberg, Marble, MartinezHumenik, Merrifield, Neville T., Newell, Roberts, Scheffel;Steadman, Tate, Todd, Cadman. CONCERNING THE V.S.S. COLORADO. WHEREAS, Many Colorado men and women have honorably served in the United States Navy and other branches of the military in the defense ofour country; and WHEREAS, Colorado is grateful to all members ofthe United States armed forces for their sacrifices and the sacrifices oftheir families; and WHEREAS, The Secretary ofthe Navy announced in April 2012 that a newVirginia-class submarine would be namedthe U.S.S. Colorado and designated SSN-788; and WHEREAS, The U.S.S. Colorado will stretch 377 feet and, in addition to its traditional attack submarine roles, will have accommodations for Navy SEALs and carry Tomahawk missiles with a striking distance of900 miles; and WHEREAS, Ithas been nearly two generations since a United States naval warship has borne the proud name ofthe great state ofColorado; and WHEREAS, This will be the fourth United States naval warship so christened, following the great traditions of the battleship U.S.S. -

The Weeping Monument: a Pre and Post Depositional Site

THE WEEPING MONUMENT: A PRE AND POST DEPOSITIONAL SITE FORMATION STUDY OF THE USS ARIZONA by Valerie Rissel April, 2012 Director of Thesis: Dr. Brad Rodgers Major Department: Program in Maritime History and Archaeology Since its loss on December 7, 1941, the USS Arizona has been slowly leaking over 9 liters of oil per day. This issue has brought about conversations regarding the stability of the wreck, and the possibility of defueling the 500,000 to 600,000 gallons that are likely residing within the wreck. Because of the importance of the wreck site, a decision either way is one which should be carefully researched before any significant changes occur. This research would have to include not only the ship and its deterioration, but also the oil’s effects on the environment. This thesis combines the historical and current data regarding the USS Arizona with case studies of similar situations so a clearer picture of the future of the ship can be obtained. THE WEEPING MONUMENT: A PRE AND POST DEPOSITIONAL SITE FORMATION STUDY OF THE USS ARIZONA Photo courtesy of Battleship Arizona by Paul Stillwell A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Program in Maritime Studies Department of History East Carolina University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Masters in Maritime History and Archaeology by Valerie Rissel April, 2012 © Valerie Rissel, 2012 THE WEEPING MONUMENT: A PRE AND POST DEPOSITIONAL SITE FORMATION STUDY OF THE USS ARIZONA by Valerie Rissel APPROVED BY: DIRECTOR OF THESIS______________________________________________________________________ Bradley Rodgers, Ph.D. COMMITTEE MEMBER________________________________________________________ Michael Palmer, Ph.D. -

216 Allan Sanford: Uss Ward

#216 ALLAN SANFORD: USS WARD Steven Haller (SH): My name is Steven Haller, and I'm here with James P. Delgado, at the Sheraton Waikiki Hotel in Honolulu, Hawaii. It's December 5, 1991, at about 5:25 PM. And we have the pleasure to be interviewing Mr. Allan Sanford. Mr. Sanford was a Seaman First Class on the USS WARD, at the time of the Pearl Harbor attack. Mr.[Sanford], Ward's gun fired what is in essence the first shot of World War II, and so it's a great pleasure to be able to be talking with you today. We're going to be doing this tape as a part of the National Park Service and ARIZONA Memorial's oral history program. We're doing it in conjunction with KHET-TV in Honolulu. So thanks again for being with us today, Mr. Sanford. Allan Sanford: It's a pleasure to be here. SH: Good. How did you get into the Navy? AS: I joined the Naval reserve unit in St. Paul, Minnesota and with two others of my classmates in high school. And we enjoyed the meetings, and uniforms, and drills, and it was a nice social activity that was a little more mature than some of the high school activities that we had participated in. So we enjoyed the meetings of the St. Paul Naval reserve. And we called it also the Minnesota Naval Militia. However, in September 1940, the commanding officer of the unit came to the meeting and said, "Attention to orders, the Minnesota Naval Militia is hereby made part of the U.S. -

Saber and Scroll Journal Volume V Issue IV Fall 2016 Saber and Scroll Historical Society

Saber and Scroll Journal Volume V Issue IV Fall 2016 Saber and Scroll Historical Society 1 © Saber and Scroll Historical Society, 2018 Logo Design: Julian Maxwell Cover Design: Cincinnatus Leaves the Plow for the Roman Dictatorship, by Juan Antonio Ribera, c. 1806. Members of the Saber and Scroll Historical Society, the volunteer staff at the Saber and Scroll Journal publishes quarterly. saberandscroll.weebly.com 2 Editor-In-Chief Michael Majerczyk Content Editors Mike Gottert, Joe Cook, Kathleen Guler, Kyle Lockwood, Michael Majerczyk, Anne Midgley, Jack Morato, Chris Schloemer and Christopher Sheline Copy Editors Michael Majerczyk, Anne Midgley Proofreaders Aida Dias, Frank Hoeflinger, Anne Midgley, Michael Majerczyk, Jack Morato, John Persinger, Chris Schloemer, Susanne Watts Webmaster Jona Lunde Academic Advisors Emily Herff, Dr. Robert Smith, Jennifer Thompson 3 Contents Letter from the Editor 5 Fleet-in-Being: Tirpitz and the Battle for the Arctic Convoys 7 Tormod B. Engvig Outside the Sandbox: Camels in Antebellum America 25 Ryan Lancaster Aethelred and Cnut: Saxon England and the Vikings 37 Matthew Hudson Praecipitia in Ruinam: The Decline of the Small Roman Farmer and the Fall of the Roman Republic 53 Jack Morato The Washington Treaty and the Third Republic: French Naval 77 Development and Rivalry with Italy, 1922-1940 Tormod B. Engvig Book Reviews 93 4 Letter from the Editor The 2016 Fall issue came together quickly. The Journal Team put out a call for papers and indeed, Saber and Scroll members responded, evidencing solid membership engagement and dedication to historical research. This issue contains two articles from Tormod Engvig. In the first article, Tormod discusses the German Battleship Tirpitz and its effect on allied convoys during WWII.