Total of 10 Pages Only May Be Xeroxed

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

KING KONG IS BACK! E D I T E D B Y David Brin with Leah Wilson

Other Titles in the Smart Pop Series Taking the Red Pill Science, Philosophy and Religion in The Matrix Seven Seasons of Buffy Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers Discuss Their Favorite Television Show Five Seasons of Angel Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers Discuss Their Favorite Vampire What Would Sipowicz Do? Race, Rights and Redemption in NYPD Blue Stepping through the Stargate Science, Archaeology and the Military in Stargate SG-1 The Anthology at the End of the Universe Leading Science Fiction Authors on Douglas Adams’ Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy Finding Serenity Anti-heroes, Lost Shepherds and Space Hookers in Joss Whedon’s Firefly The War of the Worlds Fresh Perspectives on the H. G. Wells Classic Alias Assumed Sex, Lies and SD-6 Navigating the Golden Compass Religion, Science and Dæmonology in Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials Farscape Forever! Sex, Drugs and Killer Muppets Flirting with Pride and Prejudice Fresh Perspectives on the Original Chick-Lit Masterpiece Revisiting Narnia Fantasy, Myth and Religion in C. S. Lewis’ Chronicles Totally Charmed Demons, Whitelighters and the Power of Three An Unauthorized Look at One Humongous Ape KING KONG IS BACK! E D I T E D B Y David Brin WITH Leah Wilson BENBELLA BOOKS • Dallas, Texas This publication has not been prepared, approved or licensed by any entity that created or produced the well-known movie King Kong. “Over the River and a World Away” © 2005 “King Kong Behind the Scenes” © 2005 by Nick Mamatas by David Gerrold “The Big Ape on the Small Screen” © 2005 “Of Gorillas and Gods” © 2005 by Paul Levinson by Charlie W. -

2013 Highlander Vol 97 No 2 Halloween, 2013

Regis University ePublications at Regis University Highlander - Regis University's Student-Written Archives and Special Collections Newspaper 10-31-2013 2013 Highlander Vol 97 No 2 Halloween, 2013 Follow this and additional works at: https://epublications.regis.edu/highlander Part of the Catholic Studies Commons, and the Education Commons Recommended Citation "2013 Highlander Vol 97 No 2 Halloween, 2013" (2013). Highlander - Regis University's Student-Written Newspaper. 317. https://epublications.regis.edu/highlander/317 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Archives and Special Collections at ePublications at Regis University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Highlander - Regis University's Student-Written Newspaper by an authorized administrator of ePublications at Regis University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Regis University's Highlander Volume 97, Issue 2 Halloween 2013 Kelly Fleming any one box of categories. We are more of a seasons of life, and the balance of being Social Media Editor rock band, and we always played at whatever When asked about the inspiration behind their home and traveling, and sometimes those can venue people would listen. As far as faith is song Who We Are, Foreman said, "Identity, intersect, and we can bring our families on witchfoot is a popular band that has been in concerned, 1 am very open about my faith, and it sort of tells about our journey as a band, tour." Sthe Christian and the secular music industry Christianity is faith and not just a music term, and the idea that people can tell you who you since the 1990s. -

Goodies Rule – OK?

This preview contains the first part ofChapter 14, covering the year 1976 and part of Appendix A which covers the first few episodes in Series Six of The Goodies THE GOODIES SUPER CHAPS THREE 1976 / SERIES 6 PREVIEW Kaleidoscope Publishing The Goodies: Super Chaps Three will be published on 8 November 2010 CONTENTS Introduction ..........................................................................................................................................................................................................................7 ‘Well – so much for Winchester and Cambridge’ (1940-63) ...............................................................................................9 ‘But they’re not art lovers! They’re Americans!’ (1964-65) .............................................................................................23 ‘It’s a great act! I do all the stuff!’ (1965-66) ...................................................................................................................................31 ‘Give these boys a series’ (1967) .....................................................................................................................................................................49 ‘Our programme’s gonna be on in a minute’ (1968-69)THE .......................................................................................................65 ‘We shall all be stars!’ (1969-70) .....................................................................................................................................................................87 -

Out There in the Dark There's a Beckoning Candle: Stories

OUT THERE IN THE DARK THERE’S A BECKONING CANDLE: STORIES By © Benjamin C. Dugdale, a creative writing thesis submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in partial fulfillment for the degree of Master of Arts in English Memorial University of Newfoundland April 2021 St. John’s, Newfoundland & Labrador. Abstract (200 words) OUT THERE IN THE DARK THERE’S A BECKONING CANDLE is a collection of interrelated short stories drawing from various generic influences, chiefly ‘weird,’ ‘gothic,’ ‘queer’ and ‘rural’ fiction. The collection showcases a variety of recurring characters and settings, though from one tale to the next, discrepancies, inversions, and a whelming barrage of transforming motifs force an unhomely displacement between each story, troubling reader assumptions about the various protagonists to envision a lusher plurality of possible selves and futures (a gesture towards queer spectrality, which Carla Freccero defines as the “no longer” and the “not yet”). Utilizing genres known for their unsettling and fantastical potency, the thesis constellates the complex questions of identity politics, toxic interpersonal-relationships, the brutality of capitalism, compulsory urban migration, rituals of grief, intergenerational transmission of trauma, &c., all through a corrupted mal-refracting queer prism; for example, the simple question of what discomfort recurring character Harlanne Welch, non-binary filmmaker, sees when they look into the mirror is demonstrative, when the thing in the mirror takes on its own life with far-reaching consequences. OUT THERE IN THE DARK…is an oneiric, ludic dowsing rod in pursuit of the queer prairie gothic mode just past line of sight on the horizon. ii General Summary. -

Cinephilia. Movies, Love and Memory

* pb ‘Cinephilia’ 07-06-2005 11:02 Pagina 1 The anthology Cinephilia: Movies, Love and Memory explores new periods, practices and definitions of what it means to love the cinema. [EDS.] AND HAGENER CINEPHILIA DE VALCK The essays demonstrate that beyond individu- FILM FILM alist immersion in film, typical of the cinephilia as it was popular from the 1950s to the 1970s, CULTURE CULTURE a new type of cinephilia has emerged since the IN TRANSITION IN TRANSITION 1980s, practiced by a new generation of equally devoted, but quite differently networked cine- philes. The film lover of today embraces and uses new technology while also nostalgically remembering and caring for outdated media for- mats. He is a hunter-collector as much as a mer- chant-trader, a duped consumer as much as a media-savvy producer. Marijke de Valck is a PhD candidate at the Department of Media Studies, Uni- versity of Amsterdam. Malte Hagener teaches Film and Media Studies at CinephiliaCinephilia the Department of Media Studies at the Friedrich Schiller University Jena. Movies,Movies, LoveLove andand MemoryMemory ISBN 90-5356-768-2 EDITEDEDITED BY BY MARIJKEMARIJKE DE DE VALCK VALCK MALTEMALTE HAGENER HAGENER 9 789053 567685 Amsterdam University Press AmsterdamAmsterdam UniversityUniversity PressPress WWW.AUP.NL Cinephilia Cinephilia Movies, Love and Memory Edited by Marijke de Valck and Malte Hagener Amsterdam University Press Cover design: Kok Korpershoek, Amsterdam Lay-out: japes, Amsterdam isbn 90 5356 768 2 (paperback) isbn 90 5356 769 0 (hardcover) nur 674 © Amsterdam University Press, Amsterdam 2005 All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the written permission of both the copyright owner and the author of the book. -

American Audiences on Movies and Moviegoing

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Film and Media Studies Arts and Humanities 2001 American Audiences on Movies and Moviegoing Tom Stempel Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Thanks to the University of Kentucky Libraries and the University Press of Kentucky, this book is freely available to current faculty, students, and staff at the University of Kentucky. Find other University of Kentucky Books at uknowledge.uky.edu/upk. For more information, please contact UKnowledge at [email protected]. Recommended Citation Stempel, Tom, "American Audiences on Movies and Moviegoing" (2001). Film and Media Studies. 7. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/upk_film_and_media_studies/7 American Audiences on Movies and Moviegoing This page intentionally left blank American Audiences on Movies and Moviegoing Tom Stempel THJE UNNERSITY PRESS OlF KENTUCKY Publication of this volume was made possible in part by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities. Copyright© 2001 by Tom Stempel Published by The University Press of Kentucky Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth, serving Bellarmine College, Berea College, Centre College ofKentucky, Eastern Kentucky University, The Filson Club Historical Society, Georgetown College, Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University, Morehead State University, Transylvania University, University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, and Western Kentucky University. All rights reserved. Editorial and Sales Offices: The University Press of Kentucky 663 South Limestone Street, Lexington, Kentucky 40508-4008 05 04 03 02 01 5 4 3 2 1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Stempel, Tom, 1941- American audiences on movies and moviegoing I by Tom Stempel. p. em. Includes bibliographical references. -

Why Are Comedy Films So Critically Underrated?

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Honors College 5-2012 Why are Comedy Films so Critically Underrated? Michael Arell Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/honors Part of the Dramatic Literature, Criticism and Theory Commons, and the Film and Media Studies Commons Recommended Citation Arell, Michael, "Why are Comedy Films so Critically Underrated?" (2012). Honors College. 93. https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/honors/93 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors College by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WHY ARE COMEDY FILMS SO CRITICALLY UNDERRATED? by Michael Arell A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for a Degree with Honors (Bachelor of Music in Education) The Honors College University of Maine May 2012 Advisory Committee: Michael Grillo, Associate Professor of History of Art, Advisor Ludlow Hallman, Professor of Music Annette F. Nelligan, Ed.D., Lecturer, Counselor Education Tina Passman, Associate Professor of Classical Languages and Literature Stephen Wicks, Adjunct Faculty in English © 2012 Michael Arell All Rights Reserved Abstract This study explores the lack of critical and scholarly attention given to the film genre of comedy. Included as part of the study are both existing and original theories of the elements of film comedy. An extensive look into the development of film comedy traces the role of comedy in a socio-cultural and historical manner and identifies the major comic themes and conventions that continue to influence film comedy. -

Film Terms Glossary Cinematic Terms Definition and Explanation Example (If Applicable) 180 Degree Rule a Screen Direction Rule T

Film Terms Glossary Cinematic Terms Definition and Explanation Example (if applicable) a screen direction rule that camera operators must follow - Camera placement an imaginary line on one side of the axis of action is made must adhere to the (e.g., between two principal actors in a scene), and the 180 degree rule 180 degree rule camera must not cross over that line - otherwise, there is a distressing visual discontinuity and disorientation; similar to the axis of action (an imaginary line that separates the camera from the action before it) that should not be crossed Example: at 24 fps, 4 refers to the standard frame rate or film speed - the number projected frames take 1/6 of frames or images that are projected or displayed per second to view second; in the silent era before a standard was set, many 24 frames per second films were projected at 16 or 18 frames per second, but that rate proved to be too slow when attempting to record optical film sound tracks; aka 24fps or 24p Examples: the first major 3D feature film was Bwana Devil (1953) [the first a film that has a three-dimensional, stereoscopic form or was Power of Love (1922)], House of Wax appearance, giving the life-like illusion of depth; often (1953), Cat Women of the Moon (1953), the achieved by viewers donning special red/blue (or green) or MGM musicalKiss Me Kate polarized lens glasses; when 3-D images are made (1953), Warner's Hondo (1953), House of 3-D interactive so that users feel involved with the scene, the Wax (1953), a version of Hitchcock's Dial M experience is -

The World of 3D Movies” by Eddie Sammons 12 September 2005

THE WORLD OF 3-D MOVIES Eddie Sammons Copyright 0 1992 by Eddie Sammons. A Delphi Publication. Please make note of this special copyright notice for this electronic edition of “The World of 3-D Movies” downloaded from the virtual library of the Stereoscopic Displays and Applications conference website (www.stereoscopic.org): Copyright 1992 Eddie Sammons. All rights reserved. This copy of the book is made available with the permission of the author for non-commercial purposes only. Users are granted a limited one-time license to download one copy solely for their own personal use. This edition of “The World of 3-D Movies” was converted to electronic format by Andrew Woods, Curtin University of Technology. C 0 N T E N T S. Page PROLOGUE - Introduction to the book and its contents. 1 CHAPTER 1 - 3-D. - -..THE FORMATS 2 Hopefully, the only boring part of the book but necessary if you, the reader, are to understand the technical terms. CHAPTER 2 - 3-D ..... IN THE BEGINNING .... AND NOW 5 A brief look at the history of stereoscopy with particular regard to still photography. CHAPTER 3 - 3-D ....OR NOT 3-D 12 A look at some at some of the systems that tried to be stereoscopic, those that were but not successfully so and some off-beat references to 3-D. CHAPTER 4 - 3-D. - -.- THE MOVIES, A CHRONOLOGY 25 A brief history of 3-D movies, developments in filming and presentation, festivals and revivals - CHAPTER 5 - 3-D. -..THE MOVIES 50 A filmography of all known films made in 3-D with basic credits; notation of films that may have been made in 3-D and correction of various misconceptions; cross-references to alternative titles, and possible English translations of titles; cross-reference to directors of the films listed. -

CE Junejuly18 Layout 1

<DITCHES Why are they important? CITY PAGE 7 EDITION JULY 4> Come celebrate! PAGE 8 JUNE/JULY 2018 City Begins Process to Identify Site for New Drinking Water Facility In May, the City of Westmin- new facility by early 2019 using Developing our city’s drinking quality drinking water supply ster announced the launch of a comprehensive review process water system has shaped West- originating in the Rocky Moun- Water 2025, a long-term plan- that incorporates technical and minster’s past and will play a tains. Westminster’s safe and re- ning project to replace the city’s operational requirements, as vital role in our future. Water is liable drinking water system is aging Semper Water Treatment well as significant community one of our most precious, yet fi- one of our greatest assets. Facility. The goal of the effort is engagement. nite, natural resources and we to identify the best location for a are fortunate to enjoy a high- Please see WATER on page 7 Did you know the city offers a $60 rebate for trees planted by Westminster residents? Visit www.cityofwestminster.us/ plantingprograms for program details and requirements. Longtime Westminster CITIZEN SURVEY RATES PAID Businesses Honored WESTMINSTER PRSRT STD U.S. Postage U.S. Permit No. 32 FAVORABLY At the Business Legacy Denver; Coenen Construction Westminster, CO 80031 CO Westminster, Awards in late March, the city Inc.; Colorado Sound Recording According to the 2018 citi- honored 54 businesses celebrat- Ltd.; Douglas J. Conway Inc.; zen survey, 90 percent of resi- ing their 25 to 45 year anniver- DRH Builders Inc.; Hair Styles by dents gave a favorable rating saries of doing business in Jacque; Dr. -

Movie Posters (From 1975 - 2008)

Your gateway to Movie Posters (from 1975 - 2008) Toys Models Buttons Scripts 1109 Henderson Hwy • Wpg, MB • R2L 1L4 December 2008 (204) 338-5216 • Facsimile (204) 338-5257 $5.00 MovieGeneral Posters Information • Stills • (continued) Ordering Guidelines Contents Introduction, General Information & Ordering Guidelines .......................................... Page 02 INTERNET ..................................................................................................................... Page 03 Memorabilia & Collectibles ......................................................................................... Page 04 Scripts ........................................................................................................................ Page 07 Movie Posters, Stills and more .................................................................................... Page 08 Movie Magazines ........................................................................................................ Page 31 Disney Movie Posters, Stills and more ......................................................................... Page 34 Introduction Welcome to our largest catalogue yet — 35 pages ! As usual, we have added a lot of material over the last few months. Check out all the scripts, photos, posters, presskits, back issues of Famous, Marquee and Tribute, and our ever-expanding selection of collector toys / memorabilia. Remember, if you don’t see what you are looking for, ASK! We will even send you a photograph of any item listed in this catalogue -

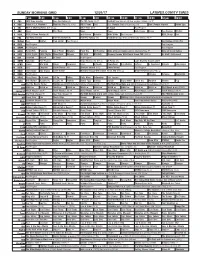

Sunday Morning Grid 12/31/17 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 12/31/17 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Football New York Jets at New England Patriots. (N) Å 4 NBC Today in L.A. Weekend Meet the Press (N) (TVG) NBC4 News Paid U.S. Olympic Trials Ski Jumping. (N) Next Olympic Hopeful Action Spo. 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News This Week News News Jack Hanna Ocean Sea Rescue Wildlife 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Mike Webb Paid Program REAL-Diego Paid 11 FOX Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Kickoff (N) FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football Chicago Bears at Minnesota Vikings. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Matter Fred Jordan Paid Program Ice Castles (2010) (PG) 18 KSCI Paid Program Paid Program 22 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 24 KVCR Paint With Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Oil Painting Anne of Green Gables (2016) Ella Ballentine. Å Anne of Green Gables 28 KCET 1001 Nights 1001 Nights Mixed Nutz Edisons Biz Kid$ Biz Kid$ Memory Rescue With Daniel Amen, MD (TVG) Å Ed Slott’s Retirement 30 ION Jeremiah Youseff In Touch Paid Program 34 KMEX Conexión Paid Program Netas Divinas (N) (TV14) Al Punto (N) Latin Grammy Awards 2017 40 KTBN James Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Jeffress K.