Barcelona a … De …

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

'Forum' Architectural Journal As an Educational

‘FORUM’ ARCHITECTURAL JOURNAL AS AN EDUCATIONAL AND SPREADING MEDIA IN THE NETHERLANDS Influences on Herman Hertzberger Rebeca Merino del Río Escuela Técnica Superior de Arquitectura, Universidad de Sevilla / Superior Technical School of Architecture, University of Seville, Seville, Spain Abstract In the sixties, the journal Forum voor Architectuur en Daarmee Verbonden Kunsten becomes the media employed by the Dutch wing of Team 10 to lecture on and spread the new architectural theories developed after the dissolution of C.I.A.M. Aldo van Eyck and Jaap Bakema head the editorial board in between 1959 and 1967. The editorial approach gravitates towards the themes defended by these young architects in the last meetings of the International Congresses of Modern Architecture, accompanied by the analysis of works of architecture that, in the editorial board’s opinion, give a correct response to the epoch’s needs. Moreover, the permeability and cross-sectional nature of the content, bring the editors’ board closer to the European architectural, cultural and artistic avant-garde. Thus, it is appreciated that similar theoretical assumptions than the ones that gave support to the different revolts that happened in Paris, London and Amsterdam between 1966 and 1968 underlie in great part of the journal’s writings. Its content is aligned parallel to the revolutionary phenomenon, contributing to some degree to it. Herman Hertzberger, a young architect who worked for years as a part of the editorial board, was highly influenced by the contents of the journal. His later dedication to education as professor at Delft University of Technology, and his association with Dutch Structuralism as well, turn him a key figure to study, because of the determining role of Forum’s acquired knowledge in his future professional activity. -

TEAM 10 out of CIAM: SOFT URBANISM + NEW BRUTALISM LA SARRAZ DECLARATION (1928) 1

TEAM 10 out of CIAM: SOFT URBANISM + NEW BRUTALISM LA SARRAZ DECLARATION (1928) 1. e idea of modern architecture includes the link between the phenomenon of architecture and the of the general economic system. 2. e idea of ‘economic eciency’ does not imply production furnishing maximum commercial prot, but production demanding a minimum work eort. 3. e need for maximum economic eciency is the inevitable result of the improvished state of the general economy. 4. e most ecient method of production is that which arises from rationalization and standardization. Rationalization and standardization act directly on working methods both in modern architecture (conception) and in the building industry (realization). 5. Rationalization and standardization react in a threefold manner: 5. Rationalization and standardization react in a threefold manner: (a) they demand of architecture conceptions leading to simplication of working methods on site and in the factory; 5. Rationalization and standardization react in a threefold manner: (a) they demand of architecture conceptions leading to simplication of working methods on site and in the factory; (b) they mean for building rms a reduction in skilled labour force; they lead to the employment of less specialized labour working under the direction of highly skilled technicians; 5. Rationalization and standardization react in a threefold manner: (a) they demand of architecture conceptions leading to simplication of working methods on site and in the factory; (b) they mean for building rms a reduction in skilled labour force; they lead to the employment of less specialized labour working under the direction of highly skilled technicians; (c) they expect from the consumer (that is to say, the customer who orders the house in which he will live) a revision of his demands in the direction of a readjustment to the new conditions of social life. -

The Politics of Friends in Modern Architecture, 1949-1987”

Title: “The politics of friends in modern architecture, 1949-1987” Name of candidate: Igea Santina Troiani, B. Arch, B. Built Env. Supervisor: Professor Jennifer Taylor This thesis was submitted as part of the requirements for the award of Doctor of Philosophy in the School of Design, Queensland University of Technology in 2005 i Key words Architecture - modern architecture; History – modern architectural history, 1949-1987; Architects - Alison Smithson, Peter Smithson, Denise Scott Brown, Robert Venturi, Elia Zenghelis, Rem Koolhaas, Philosophy - Jacques Derrida, Politics of friendship; Subversive collaboration ii Abstract This thesis aims to reveal paradigms associated with the operation of Western architectural oligarchies. The research is an examination into “how” dominant architectural institutions and their figureheads are undermined through the subversive collaboration of younger, unrecognised architects. By appropriating theories found in Jacques Derrida’s writings in philosophy, the thesis interprets the evolution of post World War II polemical architectural thinking as a series of political friendships. In order to provide evidence, the thesis involves the rewriting of a portion of modern architectural history, 1949-1987. Modern architectural history is rewritten as a series of three friendship partnerships which have been selected because of their subversive reaction to their respective establishments. They are English architects, Alison Smithson and Peter Smithson; South African born architect and planner, Denise Scott Brown and North American architect, Robert Venturi; and Greek architect, Elia Zenghelis and Dutch architect, Rem Koolhaas. Crucial to the undermining of their respective enemies is the friends’ collaboration on subversive projects. These projects are built, unbuilt and literary. Warring publicly through the writing of seminal texts is a significant step towards undermining the dominance of their ideological opponents. -

Marianna Charitonidou – Revisiting Post-CIAM Generation Proceedings

AN ACTION TOWARDS HUMANIZATION Doorn manifesto in a transnational perspective Marianna Charitonidou Postdoctoral Researcher at the School of Architecture, National Technical University of Athens and the Department of Art Theory and History Athens School of Fine Arts, Greece Abstract In 1957, Ernesto Nathan Rogers, in “Continuità o Crisi?”, published in Casabella Continuità, considered history as a process, highlighting that history can be understood as being either in a condition of continuity or in a condition of crisis “accordingly as one wishes to emphasize either permanence or emergency”. A year earlier, Le Corbusier in a diagram he sent to the tenth CIAM at Dubrovnik, he called attention to a turning point within the circle of the CIAM, maintaining that after 1956 its dominant approach had been characterised by a reorientation of the interest towards what he called “action towards humanisation”. The paper examines whether this humanising process is part of a crisis or an evolution, on the one hand, and compares the directions that were taken regarding architecture’s humanisation project within a transnational network, on the other hand. An important instance regarding this reorientation of architecture’s epistemology was the First International Conference on Proportion in the Arts at the IX Triennale di Milano in 1951, where Le Corbusier presented his Modulor and Sigfried Giedion, Matila Ghyka, Pier Luigi Nervi, Andreas Speiser and Bruno Zevi intervened among others. The debates that took place during this conference epitomise the attraction of architecture’s dominant discourse to humanisation ideals. In a different context, the Doorn manifesto (1954), signed by the architects Peter Smithson, John Voelcker, Jaap Bakema, Aldo van Eyck and Daniel van Ginkel and the economist Hans Hovens-Greve and embraced by the younger generation, is interpreted as a climax of this generalised tendency to “humanise” architectural discourse and to overcome the rejection of the rigidness of the modernist ideals. -

02 34 50 Pós 47 Ing.P65

Fabiano Borba Vianna evisiting toulouse-le mirail: r from utopia of the present to the future in the past 34 Abstract The article discusses the conception and the recent partial pós- demolition of the Toulouse-Le Mirail project, designed by the French office Candilis-Josic-Woods, relating it to the postwar period and to themes that emerged during discussions and meetings of Team 10. The meeting of Royaumont in 1962 is studied. In such occasion the project was presented by Georges Candilis and it was criticized for its large scale, revealing the position of authors such as Jaap Bakema, José Antonio Coderch, Fernando Távora and André Schimmerling, all present at the meeting. The method combines bibliographic research, investigation into Team 10 archives belonging to the collection of the Het Nieuwe Instituut in Rotterdam, as well as an empirical component with a site visit to the work. As a result, it is questioned to what extent the architectonic and urban values related to the project can be reinterpreted to support new reflections consistent with the reality of the interventions in large- scale housing settlements. Keywords Urban structures. Urban design. Modern architecture. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.11606/issn.2317-2762.v25i47p34-50 Pós, Rev. Programa Pós-Grad. Arquit. Urban. FAUUSP. São Paulo, v. 25, n. 47, p. 34-50, set-dez 2018 REVISITANDO TOULOUSE-LE MIRAIL: DA UTOPIA DO PRESENTE AO FUTURO DO PRETÉRITO pós- 35 Resumo O artigo aborda a concepção e a recente demolição parcial do projeto Toulouse-Le Mirail, de autoria do escritório francês Candilis-Josic-Woods, relacionando-o com o período do após-Guerra e com temas que emergiram durante discussões e encontros do Team 10. -

A Reassessment of the Built Work of Giancarlo De Carlo in Urbino, Italy

Understanding Place: A Reassessment of the Built Work of Giancarlo De Carlo in Urbino, Italy Mark A. Blizard, RA MD, Associate Professor The University of Texas at San Antonio, San Antonio, Texas ABSTRACT While regionalism and placed-based strategies have returned to the forefront of the design discourse in the United States––gaining acceptance as a part of sustainable practice and shaping academic curricula––the work of Giancarlo De Carlo has remained curiously in the margins. Although much has been written about the Milanese architect over the years, little is available in English. In history books, his accomplishments are limited to a few references: along with Alison and Peter Smithson, De Carlo was an important member of Team X following the general disillusionment with the CIAM and its Athens Charter. De Carlo’s initial study of Urbino (1964) is held up as a model for its consideration of place, social discourse and the role of the architect. Later, he emerged as an advocate of participatory design. Although both a writer and an educator, he left no singular treatise and was seemingly uninterested in theoretical pursuit as an end in itself. His built work, however, remains vital today––not just as a historical milestone, but for the lessons and insight that it offers. It is the purpose of this paper to gather and propose a codification of De Carlo’s understanding of place and its import to shaping architectural design. For De Carlo, design was a complex practice of back and forth negotiations between landscape (city–region–culture) and provisional design responses, each tested through the analytical process of “reading the territory”. -

NATIONAL NEWS | Fall 2005 ARTICLES DOCOMOMO NEWS 11 CONFERENCES & EVENTS

DOCOMOMO-US, P.O. Box 230977, New York, NY 10023 NY York, New 230977, Box P.O. DOCOMOMO-US, Please send this form with a check payable to DOCOMOMO-US to: DOCOMOMO-US to payable check a with form this send Please Thoughts on the Cultural Impact EMAIL ADD ME TO THE DOCOMOMO EMAIL LIST EMAIL DOCOMOMO THE TO ME ADD EMAIL [email protected] of Katrina Western Washington Western TELEPHONE FAX TELEPHONE www.docomomo-us-ntx.org In a classic scene in The Grapes of Wrath, John Steinbeck [email protected] describes the uprooting of lives and the heart-wrenching decisions CITY/STATE/ZIP North Texas North of dust-bowl victims forced to abandon their homes and leave behind the material souvenirs of their lives. Crowded into ragged www.docomomoga.org ADDRESS vehicles that will transport them westward, desperately trying to [email protected] decide what, among their belongings, they have room to carry with Georgia them, the men prepare a bonfire to burn the artifacts of their past AFFILIATION / ORGANIZATION / AFFILIATION lives—perceived as personifica- [email protected] tions of past bitterness—while Northern California Northern NAME the women lament, “How can we live without our lives? How [email protected] will we know it’s us without our (NY, CT, NJ) CT, (NY, past?” New York/Tri-State York/Tri-State New discounts on DOCOMOMO conferences. DOCOMOMO on discounts In tragic times of displace- discounts on all DOCOMOMO publications, and and publications, DOCOMOMO all on discounts lipstadt@mit-edu ment, whether brought about International Journal (published twice a year), year), a twice (published Journal International chapter. -

Expo 67, Or the Architecture of Late Modernity

Expo 67, or the Architecture of Late Modernity Inderbir Singh Riar Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy under the Executive Committee of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2014 2014 Inderbir Singh Riar All rights reserved Abstract Expo 67, or the Architecture of Late Modernity Inderbir Singh Riar The 1967 Universal and International Exhibition, the Montreal world’s fair commonly known as Expo 67, produced both continuations of and crises in the emancipatory project of modern architecture. Like many world’s fairs before it, Expo 67 was designed to mediate relations between peoples and things through its architecture. The origins of this work lay in the efforts of Daniel van Ginkel and Blanche Lemco van Ginkel, architects and town planners who, in remarkable reports, drawings, and architectural ideals advanced between 1962 and 1963, outlined the basis of a fundamentally new, though never fully realised, world’s fair in the late twentieth century. Party to the Congrès Internationaux d’Architecture Moderne and its influential prewar edicts on functionalist town planning as well as to groups like Team 10 and their opposition to diagrammatic generalisations by an emphasis on the personal, the particular, and the precise, the van Ginkels also drew on contemporary theories and practices of North American urban renewal when first conceiving Expo 67 as an instrument for redeveloping downtown Montreal. The resulting work, Man and the City, which officially secured the world’s fair bid but remained unbuilt, carefully drew on the legacies of most great exhibitions, especially those of the nineteenth century, in order to conceive of sufficiently heroic structures making immanent novel forms of human interaction, social control, and the technical organisation of space. -

Fumihiko Maki and His Theory of Collective Form: a Study on Its Practical and Pedagogical Implications Xi Qiu

Washington University in St. Louis Washington University Open Scholarship All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs) 5-2013 Fumihiko Maki and His Theory of Collective Form: A Study on Its Practical and Pedagogical Implications Xi Qiu Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/etd Part of the Architectural History and Criticism Commons Recommended Citation Qiu, Xi, "Fumihiko Maki and His Theory of Collective Form: A Study on Its Practical and Pedagogical Implications" (2013). All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs). 936. https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/etd/936 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs) by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY IN ST. LOUIS Department of Architecture Dissertation Examination Committee: Robert McCarter, Chair Eric Mumford Seng Kuan Fumihiko Maki and His Theory of Collective Form: A Study on Its Practical and Pedagogical Implications by Xi Qiu A dissertation presented to the Graduate School of Design and Visual Arts of Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Architectural Pedagogy May 2013 ST. LOUIS, MISSOURI Acknowledgements Working on this year-long dissertation project has been a truly once-in-a-lifetime experience. I cannot imagine that it could have come to a completion without the help of so many people. I am grateful and deeply indebted to all those who helped me along the way through sharing their knowledge, providing me with material, and offering their guidance and support. -

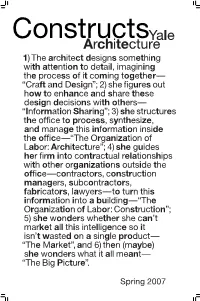

Yale Architecture

Yale Architecture 1) The architect designs something with attention to detail, imagining the process of it coming together— “Craft and Design”; 2) she figures out how to enhance and share these design decisions with others— “Information Sharing”; 3) she structures the office ot process, synthesize, and manage this information inside the office—“The Organization of Labor: Architecture”; 4) she guides her firm into contractual relationships with other organizations outside the office—contractors, construction managers, subcontractors, fabricators, lawyers—to turn this information into a building—“The Organization of Labor: Construction”; 5) she wonders whether she can’t market all this intelligence so it isn’t wasted on a single product— “The Market”, and 6) then (maybe) she wonders what it all meant— “The Big Picture”. Spring 2007 Constructs To form by putting together parts; build; frame; devise. A complex image or idea resulting from synthesis by the mind. 2 A Conversation with Roger Madelin Roger 4 A Conversation with Ali Rahim 5 Eero Saarinen: Shaping the Future, exhibition review by Aino Niskanen; book review by Eric Mumford 6 “Building (in) the Future: Recasting Labor in Architecture,” a review by Ted Whitten and J. Brantley Hightower 8 Team 10: A Utopia of the Present, exhibition Madelin review by Christian Rattemeyer; “Team 10 Today,” symposium review by Claire Weisz 10 Some Assembly Required exhibition review by Michael Tower 11 Decoration, a discussion at the Architectural League of New York 12 Yale University Art Gallery, Restoring Kahn by Carter Wiseman; Raw Geometry by Hilary Sample 13 Histories of British Architecture by Claire Zimmerman; Architecture of Democracy, a Conversation by Melissa Delvecchio Roger Madelin, of London, is the third a robust piece of the city where the risk and 16 Book Reviews: Sandy Isenstadt’s The Modern Edward P. -

Delft University of Technology Architecture and Democracy

Delft University of Technology Architecture and democracy Contestations in and of the open society van den Heuvel, Dirk Publication date 2018 Document Version Final published version Published in Jaap Bakema and the Open Society Citation (APA) van den Heuvel, D. (2018). Architecture and democracy: Contestations in and of the open society. In D. van den Heuvel (Ed.), Jaap Bakema and the Open Society (pp. 240-257). Archis. Important note To cite this publication, please use the final published version (if applicable). Please check the document version above. Copyright Other than for strictly personal use, it is not permitted to download, forward or distribute the text or part of it, without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), unless the work is under an open content license such as Creative Commons. Takedown policy Please contact us and provide details if you believe this document breaches copyrights. We will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. This work is downloaded from Delft University of Technology. For technical reasons the number of authors shown on this cover page is limited to a maximum of 10. Green Open Access added to TU Delft Institutional Repository ‘You share, we take care!’ – Taverne project https://www.openaccess.nl/en/you-share-we-take-care Otherwise as indicated in the copyright section: the publisher is the copyright holder of this work and the author uses the Dutch legislation to make this work public. Dirk van den Heuvel (ed.) M. Christine Boyer Dick van Gameren Carola Hein Jorrit Sipkes Arnold Reijndorp Jaap Bakema and the open society interviews with: Brita Bakema Herman Hertzberger Carel Weeber Frans Hooykaas John Habraken Izak Salomons photographs by: Lard Buurman Johannes Schwartz 10 10 Archis Publishers 11 2 2 Lard Buurman photographs Patterns of use 14 Guus Beumer Preface 14 16 Dirk van den Heuvel The elusive bigness of Bakema A man with a mission 26 M. -

Contemporary Architecture

CONTEMPORARY ARCHITECTURE UNIT-1 M T V REDDY Challenging CIAM declaration Team X and Brutalism Writings of jane Jacobs Robert venturi Christopher alexander CIAM’s Declaration (1928) Translated by Michael Bullock. From Programs and Manifestoes on 20th-Century Architecture. (The MIT Press. Cambridge, MA: 1971). The undersigned architects, representing the national groups of modern architects, affirm their unity of viewpoint regarding the fundamental conceptions of architecture and their professional obligations towards society. They insist particularly on the fact that “building” is an elementary activity of man intimately linked with evolution and the development of human life. The destiny of architecture is to express the orientation of the age. Works of architecture can spring only from the present time. They therefore refuse categorically to apply in their working methods means that may have been able to illustrate past societies; they affirm today the need for a new conception of architecture that satisfies the spiritual, intellectual, and material demands of present-day life. Conscious of the deep disturbances of the social structure brought about by machines, they recognize that the transformation of the economic order and of social life inescapably brings with it a corresponding transformation of the architectural phenomenon. The intention that brings them together here is to attain the indispensable and urgent harmonization of the elements involved by replacing architecture on its true plane, the economic, and sociological plane. Thus architecture must be set free from the sterilizing grip of the academies that are concerned with preserving the formulas of the past. Animated by this conviction, they declare themselves members of an association and will give each other mutual support on the international plane with a view to realizing their aspirations morally and materially.