Rethinking Church and State During the English Interregnum Charles W. A. Prior

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Politics of Liberty in England and Revolutionary America

P1: IwX/KaD 0521827450agg.xml CY395B/Ward 0 521 82745 0 May 7, 2004 7:37 The Politics of Liberty in England and Revolutionary America LEE WARD Campion College University of Regina iii P1: IwX/KaD 0521827450agg.xml CY395B/Ward 0 521 82745 0 May 7, 2004 7:37 published by the press syndicate of the university of cambridge The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge, United Kingdom cambridge university press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge cb2 2ru, uk 40 West 20th Street, New York, ny 10011-4211, usa 477 Williamstown Road, Port Melbourne, vic 3207, Australia Ruiz de Alarcon´ 13, 28014 Madrid, Spain Dock House, The Waterfront, Cape Town 8001, South Africa http://www.cambridge.org C Lee Ward 2004 This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published 2004 Printed in the United States of America Typeface Sabon 10/12 pt. System LATEX 2ε [tb] A catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Ward, Lee, 1970– The politics of liberty in England and revolutionary America / Lee Ward p. cm. Includes bibliographical references (p. ) and index. isbn 0-521-82745-0 1. Political science – Great Britain – Philosophy – History – 17th century. 2. Political science – Great Britain – Philosophy – History – 18th century. 3. Political science – United States – Philosophy – History – 17th century. 4. Political science – United States – Philosophy – History – 18th century. 5. United States – History – Revolution, 1775–1783 – Causes. -

Part I Background and Summary

PART I BACKGROUND AND SUMMARY Chapter 1 BRITISH STATUTES IN IDSTORICAL PERSPECTIVE The North American plantations were not the earliest over seas possessions of the English Crown; neither were they the first to be treated as separate political entities, distinct from the realm of England. From the time of the Conquest onward, the King of England held -- though not necessarily simultaneously or continuously - a variety of non-English possessions includ ing Normandy, Anjou, the Channel Islands, Wales, Jamaica, Scotland, the Carolinas, New-York, the Barbadoes. These hold ings were not a part of the Kingdom of England but were govern ed by the King of England. During the early medieval period the King would issue such orders for each part of his realm as he saw fit. Even as he tended to confer more and more with the officers of the royal household and with the great lords of England - the group which eventually evolved into the Council out of which came Parliament - with reference to matters re lating to England, he did likewise with matters relating to his non-English possessions.1 Each part of the King's realm had its own peculiar laws and customs, as did the several counties of England. The middle ages thrived on diversity and while the King's writ was acknowledged eventually to run throughout England, there was little effort to eliminate such local practices as did not impinge upon the power of the Crown. The same was true for the non-Eng lish lands. An order for one jurisdictional entity typically was limited to that entity alone; uniformity among the several parts of the King's realm was not considered sufficiently important to overturn existing laws and customs. -

Cromwelliana 2012

CROMWELLIANA 2012 Series III No 1 Editor: Dr Maxine Forshaw CONTENTS Editor’s Note 2 Cromwell Day 2011: Oliver Cromwell – A Scottish Perspective 3 By Dr Laura A M Stewart Farmer Oliver? The Cultivation of Cromwell’s Image During 18 the Protectorate By Dr Patrick Little Oliver Cromwell and the Underground Opposition to Bishop 32 Wren of Ely By Dr Andrew Barclay From Civilian to Soldier: Recalling Cromwell in Cambridge, 44 1642 By Dr Sue L Sadler ‘Dear Robin’: The Correspondence of Oliver Cromwell and 61 Robert Hammond By Dr Miranda Malins Mrs S C Lomas: Cromwellian Editor 79 By Dr David L Smith Cromwellian Britain XXIV : Frome, Somerset 95 By Jane A Mills Book Reviews 104 By Dr Patrick Little and Prof Ivan Roots Bibliography of Books 110 By Dr Patrick Little Bibliography of Journals 111 By Prof Peter Gaunt ISBN 0-905729-24-2 EDITOR’S NOTE 2011 was the 360th anniversary of the Battle of Worcester and was marked by Laura Stewart’s address to the Association on Cromwell Day with her paper on ‘Oliver Cromwell: a Scottish Perspective’. ‘Risen from Obscurity – Cromwell’s Early Life’ was the subject of the study day in Huntingdon in October 2011 and three papers connected with the day are included here. Reflecting this subject, the cover illustration is the picture ‘Cromwell on his Farm’ by Ford Madox Brown (1821–1893), painted in 1874, and reproduced here courtesy of National Museums Liverpool. The painting can be found in the Lady Lever Art Gallery in Port Sunlight Village, Wirral, Cheshire. In this edition of Cromwelliana, it should be noted that the bibliography of journal articles covers the period spring 2009 to spring 2012, addressing gaps in the past couple of years. -

Von Greyerz Translated by Thomas Dunlap

Religion and Culture in Early Modern Europe, 1500–1800 This page intentionally left blank Religion and Culture in Early Modern Europe, 1500–1800 kaspar von greyerz translated by thomas dunlap 1 2008 1 Oxford University Press, Inc., publishes works that further Oxford University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education. Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offices in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Copyright # 2008 by Oxford University Press, Inc. Published by Oxford University Press, Inc. 198 Madison Avenue, New York, New York 10016 www.oup.com Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Oxford University Press. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Greyerz, Kaspar von. [Religion und Kultur. English] Religion and culture in early modern Europe, 1500–1800 / Kaspar von Greyerz ; Translated by Thomas Dunlap. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN: 978-0-19-532765-6 (cloth); 978-0-19-532766-3 (pbk.) 1. Religion and culture—Europe—History. 2. Europe—Religious life and customs. I. Title. BL65.C8G7413 2007 274'.06—dc22 2007001259 987654321 Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper To Maya Widmer This page intentionally left blank Preface When I wrote the foreword to the original German edition of this book in March 2000, I took the secularized social and cultural cli- mate in which Europeans live today as a reason for reminding the reader of the special effort he or she had to make in order to grasp the central role of religion in the cultures and societies of early modern Europe. -

Thomas Erastus Oor Die Struktuur Van Die Gemeenskap'^

Thomas Erastus oor die struktuur van die gemeenskap’^ A D Pont Abstract Thomas Erastus on the Church, the rulers and the community In this, largely desCriptive paper, the views of Thomas Erastus (1520-1583) of Heidelberg, are discussed. Erastus' views on the church, the rulers and the community are put forward in his Treatise Explicatio gravissimae of 1568-69, published in 1589. It is clear that Erastus depends on the Zurich covenant-theology in his view that the community is essentially a Christian community ruled by the pius magistratus. In this community the church does not appear as a separate coetus or societas, but is ruled by the godly prinCe who rules according to God's law. Erastus' view gained popularity in the ecclesia AngUcam and was, to a certain extent, also a plea for the divine rights of kings. INLEIDENDE OPMERKINGS Dit is duidelik dat die sestiende eeu 'n tyd was waarin baie dinge wat uit die verlede gestam het, in duie gestort het en dat op baie vlakke nuwe insigte na vore gekom het. Dit was nie net op die kerklik-gods- dienstige vlak waar, danksy die arbeid én insigte van Martin Luther, geweldige veranderings plaasgevind het nie, maar ook op die staatkun- dig-politieke én kulturele vlak, is baie veranderings te konstateer. Die bewegings van die RenaissanCe en die Humanisme, verwant aan me- kaar en tog verskillend van inhoud, die opkoms van die nasionale state, die verbrokkeling van die godsdienstig-kerklik-bepaalde eenheid- struktuur en kultuur van die Middeleeue, dui alles op die veranderings wat besig was om plaas te vind. -

The English Civil Wars a Beginner’S Guide

The English Civil Wars A Beginner’s Guide Patrick Little A Oneworld Paperback Original Published in North America, Great Britain and Australia by Oneworld Publications, 2014 Copyright © Patrick Little 2014 The moral right of Patrick Little to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted by him/her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 All rights reserved Copyright under Berne Convention A CIP record for this title is available from the British Library ISBN 9781780743318 eISBN 9781780743325 Typeset by Siliconchips Services Ltd, UK Printed and bound in Denmark by Nørhaven A/S Oneworld Publications 10 Bloomsbury Street London WC1B 3SR England Stay up to date with the latest books, special offers, and exclusive content from Oneworld with our monthly newsletter Sign up on our website www.oneworld-publications.com Contents Preface vii Map of the English Civil Wars, 1642–51 ix 1 The outbreak of war 1 2 ‘This war without an enemy’: the first civil war, 1642–6 17 3 The search for settlement, 1646–9 34 4 The commonwealth, 1649–51 48 5 The armies 66 6 The generals 82 7 Politics 98 8 Religion 113 9 War and society 126 10 Legacy 141 Timeline 150 Further reading 153 Index 157 Preface In writing this book, I had two primary aims. The first was to produce a concise, accessible account of the conflicts collectively known as the English Civil Wars. The second was to try to give the reader some idea of what it was like to live through that trau- matic episode. -

The Reception of Hobbes's Leviathan

This is a repository copy of The reception of Hobbes's Leviathan. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/71534/ Version: Published Version Book Section: Parkin, Jon (2007) The reception of Hobbes's Leviathan. In: Springborg, Patricia, (ed.) The Cambridge Companion to Hobbes's Leviathan. The Cambridge Companions to Philosophy, Religion and Culture . Cambridge University Press , Cambridge , pp. 441-459. https://doi.org/10.1017/CCOL0521836670.020 Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ jon parkin 19 The Reception of Hobbes’s Leviathan The traditional story about the reception of Leviathan was that it was a book that was rejected rather than read seriously.1 Leviathan’s perverse amalgamation of controversial doctrine, so the story goes, earned it universal condemnation. Hobbes was outed as an athe- ist and discredited almost as soon as the work appeared. Subsequent criticism was seen to be the idle pursuit of a discredited text, an exer- cise upon which young militant churchmen could cut their teeth, as William Warburton observed in the eighteenth century.2 We need to be aware, however, that this was a story that was largely the cre- ation of Hobbes’s intellectual opponents, writers with an interest in sidelining Leviathan from the mainstream of the history of ideas. -

Calvinism in America

Nebula7.4, December 2010 Participation, Democracy, and the Split in Revolutionary Calvinism, 1641 – 1646. By Tod Moore & Graham Maddox Abstract During the early phase of the revolutionary period in Britain (1641-46) an ideological divergence took place between fractions labelled Independent and Presbyterian. Our study of printed sources for this period uses debates over the meaning and relevance of the Greek term „democracy‟ to attempt a mapping of these emergent ideologies within revolutionary Calvinism. We find a contested social terrain with the Presbyterians supporting the revolutions from a socially conservative position and the Independents favouring radical social change. The years 1641 to 1646 saw “a transformation of the political nation, the beginning of mass politics, and a rapid and revolutionary expansion of what is sometimes called the „public sphere‟ [which] brought “men that do not rule” (and sometimes women too) into active engagement with public affairs” (Cressy 2003: 68). In particular there were a great number of books and pamphlets written by the leading Calvinists and these reveal a surprising amount of interest in democracy. A modern consensus that democracy did not come into fashion as an idea until the mid-nineteenth century is questioned by the prominence given to democracy in the controversy over the reconstruction of the church between the Presbyterians and the Independents in the 1640s. We know that “democracy” survived from ancient times within the “mixed constitution,” where it was blended with monarchy and aristocracy. We ask whether the strains of conflict, especially the attitudes and practises of the Independents, loosened the internal bonds of the mixed constitution, undermining claims of kingship and challenging elites. -

The Medieval Parliament

THE MEDIEVAL PARLIAMENT General 4006. Allen, John. "History of the English legislature." Edinburgh Review 35 (March-July 1821): 1-43. [Attributed in the Wellesley Index; a review of the "Reports on the Dignity of a Peer".] 4007. Arnold, Morris S. "Statutes as judgments: the natural law theory of parliamentary activities in medieval England." University of Pennsylvania Law Review 126 (1977-78): 329-43. 4008. Barraclough, G. "Law and legislation in medieval England." Law Quarterly Review 56 (1940): 75-92. 4009. Bemont, Charles. "La séparation du Parlement anglais en deux Chambres." In Actes du premier Congrès National des Historiens Français. Paris 20-23 Avril 1927, edited by Comite Français des Sciences Historiques: 33-35. Paris: Éditions Rieder, 1928. 4010. Betham, William. Dignities, feudal and parliamentary, and the constitutional legislature of the United Kingdom: the nature and functions of the Aula Regis, the Magna Concilia and the Communa Concilia of England, and the history of the parliaments of France, England, Scotland, and Ireland, investigated and considered with a view to ascertain the origin, progress, and final establishment of legislative parliaments, and the dignity of a peer, or Lord of Parliament. London: Thomas and William Boone, 1830. xx, 379p. [A study of the early history of the Parliaments of England, Ireland and Scotland, with special emphasis on the peerage; Vol. I only published.] 4011. Bodet, Gerald P. Early English parliaments: high courts, royal councils, or representative assemblies? Problems in European civilization. Boston, Mass.: Heath, 1967. xx,107p. [A collection of extracts from leading historians.] 4012. Boutmy, E. "La formation du Parlement en Angleterre." Revue des Deux Mondes 68 (March-April 1885): 82-126. -

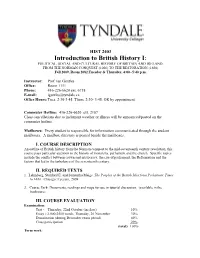

Introduction to British History I

HIST 2403 Introduction to British History I: POLITICAL, SOCIAL AND CULTURAL HISTORY OF BRITAIN AND IRELAND, FROM THE NORMAN CONQUEST (1066) TO THE RESTORATION (1660) Fall 2009, Room 2082,Tuesday & Thursday, 4:00--5:40 p.m. Instructor: Prof. Ian Gentles Office: Room 1111 Phone: 416-226-6620 ext. 6718 E-mail: [email protected] Office Hours: Tues. 2:30-3:45, Thurs. 2:30- 3:45, OR by appointment Commuter Hotline: 416-226-6620 ext. 2187 Class cancellations due to inclement weather or illness will be announced/posted on the commuter hotline. Mailboxes: Every student is responsible for information communicated through the student mailboxes. A mailbox directory is posted beside the mailboxes. I. COURSE DESCRIPTION An outline of British history from the Norman conquest to the mid-seventeenth century revolution, this course pays particular attention to the history of monarchy, parliament and the church. Specific topics include the conflict between crown and aristocracy, the rise of parliament, the Reformation and the factors that led to the turbulence of the seventeenth century. II. REQUIRED TEXTS 1. Lehmberg, Stanford E. and Samantha Meigs. The Peoples of the British Isles from Prehistoric Times to 1688 . Chicago: Lyceum, 2009 2. Course Pack: Documents, readings and maps for use in tutorial discussion. (available in the bookstore) III. COURSE EVALUATION Examination : Test - Thursday, 22nd October (in class) 10% Essay - 2,000-2500 words, Thursday, 26 November 30% Examination (during December exam period) 40% Class participation 20% (total) 100% Term work : a. You are expected to attend the tutorials, preparing for them through the lectures and through assigned reading. -

The Dissenting Tradition in English Medicine of the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries

Medical History, 1995, 39: 197-218 The Dissenting Tradition in English Medicine of the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries WILLIAM BIRKEN* In England, medicine has always been something of a refuge for individuals whose lives have been dislocated by religious and political strife. This was particularly true in the seventeenth century when changes in Church and State were occurring at a blinding speed. In his book The experience of defeat, Christopher Hill has described the erratic careers of a number of radical clergy and intellectuals who studied and practised medicine in times of dislocation. A list pulled together from Hill's book would include: John Pordage, Samuel Pordage, Henry Stubbe, John Webster, John Rogers, Abiezer Coppe, William Walwyn and Marchamont Nedham.1 Medicine as a practical option for a lost career, or to supplement and subsidize uncertain careers, can also be found among Royalists and Anglicans when their lives were similarly disrupted during the Interregnum. Among these were the brilliant Vaughan twins, Thomas, the Hermetic philosopher, and Henry, the metaphysical poet and clergyman; the poet, Abraham Cowley; and the mercurial Nedham, who was dislocated both as a republican and as a royalist. The Anglicans Ralph Bathurst and Mathew Robinson were forced to abandon temporarily their clerical careers for medicine, only to return to the Church when times were more propitious. In the middle of the eighteenth century the political and religious disabilities of non-juring Anglicanism were still potent enough to impel Sir Richard Jebb to a successful medical career. But by and large the greatest impact on medicine came from the much larger group of the displaced, the English Dissenters, whose combination of religion and medicine were nothing short of remarkable. -

Download (491Kb)

Original citation: Anstey, Peter R. and Vanzo, Alberto (2016) Early modern experimental philosophy. In: Sytsma, Justin and Buckwalter, Wesley, (eds.) A Companion to Experimental Philosophy. Blackwell Companions to Philosophy Series . Wiley-Blackwell, pp. 87-102. Permanent WRAP URL: http://wrap.warwick.ac.uk/78705 Copyright and reuse: The Warwick Research Archive Portal (WRAP) makes this work by researchers of the University of Warwick available open access under the following conditions. Copyright © and all moral rights to the version of the paper presented here belong to the individual author(s) and/or other copyright owners. To the extent reasonable and practicable the material made available in WRAP has been checked for eligibility before being made available. Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. Publisher’s statement: Published source: Anstey, Peter R. and Vanzo, Alberto (2016) Early modern experimental philosophy. In: Sytsma, Justin and Buckwalter, Wesley, (eds.) A Companion to Experimental Philosophy. Blackwell Companions to Philosophy Series . Wiley-Blackwell, pp. 87-102 Copyright © 2016 by John Wiley & Sons, Link to the full title: http://www.wiley.com/WileyCDA/WileyTitle/productCd- 1118661699.html A note on versions: The version presented here may differ from the published version or, version of record, if you wish to cite this item you are advised to consult the publisher’s version.